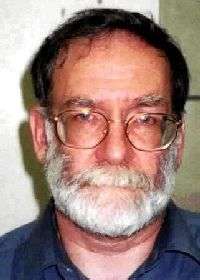

Harold Shipman

Harold Frederick Shipman (14 January 1946 – 13 January 2004), known to acquaintances as Fred Shipman, was an English general practitioner who is believed to be the most prolific serial killer in modern history. On 31 January 2000, a jury found Shipman guilty of the murder of fifteen patients under his care, with his total number of victims approximately 250. Shipman was sentenced to life imprisonment with the recommendation that he never be released.[4] He committed suicide by hanging on 13 January 2004, a day before his 58th birthday, in his cell at Wakefield Prison.

Harold Shipman | |

|---|---|

Shipman c. 2000 | |

| Born | Harold Frederick Shipman 14 January 1946 Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Died | 13 January 2004 (aged 57) HM Prison Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England |

| Cause of death | Suicide by hanging |

| Other names | |

| Occupation | General practitioner |

| Spouse(s) | Primrose Oxtoby

( m. 1966; |

| Children | 4 |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment (Whole life order) plus 4 years for forgery |

| Details | |

| Victims | 215–265+[3] |

Span of crimes | 1975–1998 |

| Country | England |

Date apprehended | 7 September 1998 |

The Shipman Inquiry, a two-year-long investigation of all deaths certified by Shipman, which was chaired by Dame Janet Smith, examined Shipman's crimes. The inquiry identified 215 victims and estimated his total victim count at 250, about 80 per cent of whom were elderly women. Shipman's youngest confirmed victim was a 41-year-old man, although "significant suspicion" arose that he had killed patients as young as four.[3][5]

Much of the United Kingdom's legal structure concerning health care and medicine was reviewed and modified as a result of Shipman's crimes. He is the only British doctor to have been found guilty of murdering his patients, although other doctors have been acquitted of similar crimes or convicted on lesser charges.[6]

Early life and career

Harold Frederick Shipman was born on the Bestwood council estate[7] in Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England, the second of the three children of Harold Frederick Shipman (12 May 1914 – 5 January 1985), a lorry driver, and Vera Brittan (23 December 1919 – 21 June 1963).[8][9] His working-class parents were devout Methodists.[8][9] When growing up, Shipman was an accomplished rugby player in youth leagues.

Shipman passed his eleven-plus in 1957, moving to High Pavement Grammar School, Nottingham, which he left in 1964. He excelled as a distance runner, and in his final year at school served as vice-captain of the athletics team. Shipman was particularly close to his mother, who died of lung cancer when he was aged 17.[10][9][11] Her death came in a manner similar to what later became Shipman's own modus operandi: in the later stages of her disease, she had morphine administered at home by a doctor. Shipman witnessed his mother's pain subside, despite her terminal condition, until her death on 21 June 1963.[12]

On 5 November 1966, Shipman married Primrose May Oxtoby. They had four children together.

Shipman studied medicine at Leeds School of Medicine, graduating in 1970.[13] He began working at Pontefract General Infirmary in Pontefract, West Riding of Yorkshire, and in 1974 took his first position as a general practitioner (GP) at the Abraham Ormerod Medical Centre in Todmorden. In the following year, he was caught forging prescriptions of pethidine (Demerol) for his own use. Shipman was fined £600, and briefly attended a drug rehabilitation clinic in York. He became a GP at the Donneybrook Medical Centre in Hyde near Manchester, in 1977.[13][14]

Shipman continued working as a GP in Hyde throughout the 1980s, and established his own surgery at 21 Market Street in 1993, becoming a respected member of the community. In 1983, he was interviewed in an edition of the Granada Television documentary World in Action on how the mentally ill should be treated in the community.[15] A year after his conviction, the interview was re-broadcast on Tonight with Trevor McDonald.[16]

Detection

In March 1998, Linda Reynolds of the Brooke Surgery in Hyde, prompted by Deborah Massey from Frank Massey and Sons funeral parlour, expressed concerns to John Pollard, the coroner for the South Manchester District, about the high death rate among Shipman's patients. In particular, she was concerned about the large number of cremation forms for elderly women that he had needed countersigned. The matter was brought to the attention of the police, who were unable to find sufficient evidence to bring charges; the Shipman Inquiry later blamed the police for assigning inexperienced officers to the case. Between 17 April 1998, when the police abandoned the investigation, and Shipman's eventual arrest, he killed three more people.[17][18] Several months later, Hyde taxi driver John Shaw contacted the police, informing them that he suspected Shipman of murdering twenty-one of his patients.[19]

Shipman's last victim was Kathleen Grundy, who was found dead at her home on 24 June 1998. He was the last person to see her alive; he later signed her death certificate, recording "old age" as the cause of death. Grundy's daughter, lawyer Angela Woodruff, became concerned when solicitor Brian Burgess informed her that a will had been made, apparently by her mother; there were doubts about its authenticity. The will excluded Woodruff and her children, but left £386,000 to Shipman. At Burgess's urging, Woodruff went to the police, who began an investigation. Grundy's body was exhumed and when examined, was found to contain traces of diamorphine (heroin), often used for pain control in terminal cancer patients. Shipman claimed that she was an addict, and showed them comments he had written to that effect in his computerised medical journal; however, examination of his computer showed that they were written after her death. Shipman was arrested on 7 September 1998, and was found to own a Brother typewriter of the kind used to make the forged will.[20]

The police then investigated other deaths Shipman had certified, and created a list of fifteen specimen cases to investigate. They discovered a pattern of his administering lethal doses of diamorphine, signing patients' death certificates, and then falsifying medical records to indicate that they had been in poor health.[21]

Prescription For Murder, a 2000 book by journalists Brian Whittle and Jean Ritchie, advanced two theories on Shipman's motive for forging the will: that he wanted to be caught because his life was out of control, or that he planned to retire at the age of 55 and leave the UK.[22]

In 2003, David Spiegelhalter et al. suggested that "statistical monitoring could have led to an alarm being raised at the end of 1996, when there were 67 excess deaths in females aged over 65 years, compared with 119 by 1998."[23]

Trial and imprisonment

Shipman's trial began at Preston Crown Court on 5 October 1999. He was charged with the murders of 15 women by lethal injections of diamorphine, all between 1995 and 1998.

- Marie West

- Irene Turner

- Lizzie Adams

- Jean Lilley

- Ivy Lomas

- Muriel Grimshaw

- Marie Quinn

- Kathleen Wagstaff

- Bianka Pomfret

- Norah Nuttall

- Pamela Hillier

- Maureen Ward

- Winifred Mellor

- Joan Melia

- Kathleen Grundy

His legal representatives tried unsuccessfully to have the Grundy case, where a clear motive was alleged, tried separately from the others where no motive was apparent.

On 31 January 2000, after six days of deliberation, the jury found Shipman guilty of fifteen counts of murder and one count of forgery. Mr Justice Forbes subsequently sentenced Shipman to life imprisonment on all fifteen counts of murder, with a recommendation that he never be released, to be served concurrently with a sentence of four years for forging Grundy's will.[24] On 11 February, ten days after his conviction, the General Medical Council (GMC) formally struck Shipman off its register. Two years later, Home Secretary David Blunkett confirmed the judge's whole life tariff, just months before British government ministers lost their power to set minimum terms for prisoners.[25][26] While authorities could have brought many additional charges, they concluded that a fair hearing would be impossible in view of the enormous publicity surrounding the original trial. Furthermore, the fifteen life sentences already handed down rendered further litigation unnecessary.[27][28]

Shipman consistently denied his guilt, disputing the scientific evidence against him. He never made any public statements about his actions. Shipman's wife, Primrose, steadfastly maintained her husband's innocence, even after his conviction.[29]

Shipman is the only doctor in the history of British medicine found guilty of murdering his patients.[30] John Bodkin Adams was charged in 1957 with murdering a patient, amid rumours he had killed dozens more over a 10-year period and "possibly provided the role model for Shipman". However, he was acquitted.[31] Historian Pamela Cullen has argued that because of Adams' acquittal, there was no impetus to examine the flaws in the British legal system until the Shipman case.[32]

Death

Shipman hanged himself in his cell at Wakefield Prison at 6:20 am on 13 January 2004, on the eve of his 58th birthday, and was pronounced dead at 8:10 am. A Prison Service statement indicated that Shipman had hanged himself from the window bars of his cell using bed sheets.[33]

Some of the victims' families said they felt cheated, as Shipman's suicide meant they would never have the satisfaction of his confession, nor answers as to why he committed his crimes.[34] Home Secretary David Blunkett noted that celebration was tempting, saying: "You wake up and you receive a call telling you Shipman has topped himself and you think, is it too early to open a bottle? And then you discover that everybody's very upset that he's done it."[35]

Shipman's death divided national newspapers, with the Daily Mirror branding him a "cold coward" and condemning the Prison Service for allowing his suicide to happen. However, The Sun ran a celebratory front-page headline; "Ship Ship hooray!"[36] The Independent called for the inquiry into Shipman's suicide to look more widely at the state of Britain's prisons as well as the welfare of inmates.[37] In The Guardian, an article by Sir David Ramsbotham, a former Chief Inspector of Prisons, suggested that whole life sentencing be replaced by indefinite sentencing, for this would at least give prisoners the hope of eventual release and reduce the risk of their ending their own lives by suicide as well as making their management easier for prison officials.[37]

Shipman's motive for suicide was never established, though he reportedly told his probation officer that he was considering suicide to assure his wife's financial security after he was stripped of his NHS pension.[38] Primrose Shipman received a full NHS pension; she would not have been entitled to it if Shipman had lived past 60.[39] Additionally, there was evidence that Primrose, who had consistently protested Shipman's innocence despite the overwhelming evidence, had begun to suspect his guilt. Shipman refused to take part in courses which would have encouraged acknowledgement of his crimes, leading to a temporary removal of privileges, including the opportunity to telephone his wife.[39][40] During this period, according to Shipman's cellmate, he received a letter from Primrose exhorting him to, "Tell me everything, no matter what."[29] A 2005 inquiry found that Shipman's suicide "could not have been predicted or prevented," but that procedures should nonetheless be re-examined.[39]

Aftermath

In January 2001, Chris Gregg, a senior West Yorkshire detective, was selected to lead an investigation into 22 of the West Yorkshire deaths.[41] Following this, the Shipman Inquiry, submitted in July 2002, concluded that he had killed at least 215 of his patients between 1975 and 1998, during which time he practiced in Todmorden (1974–1975) and Hyde (1977–1998). Dame Janet Smith, the judge who submitted the report, admitted that many more deaths of a suspicious nature could not be definitively ascribed to Shipman. Most of his victims were elderly women in good health.[3]

In her sixth and final report, issued on 24 January 2005, Smith reported that she believed that Shipman had killed three patients, and she had serious suspicions about four further deaths, including that of a four-year-old girl, during the early stage of his medical career at Pontefract General Infirmary. In total, 459 people died while under his care between 1971 and 1998, but it is uncertain how many of those were murder victims, as he was often the only doctor to certify a death. Smith's estimate of Shipman's total victim count over that 27-year period was 250.[3][5]

The GMC charged six doctors, who signed cremation forms for Shipman's victims, with misconduct, claiming they should have noticed the pattern between Shipman's home visits and his patients' deaths. All these doctors were found not guilty. In October 2005, a similar hearing was held against two doctors who worked at Tameside General Hospital in 1994, who failed to detect that Shipman had deliberately administered a "grossly excessive" dose of morphine.[42][43] The Shipman Inquiry recommended changes to the structure of the GMC.[44]

In 2005, it came to light that Shipman may have stolen jewellery from his victims. In 1998, police had seized over £10,000 worth of jewellery they found in his garage. In March 2005, when Primrose Shipman asked for its return, police wrote to the families of Shipman's victims asking them to identify the jewellery.[45][46][47] Unidentified items were handed to the Assets Recovery Agency in May.[48] The investigation ended in August. Authorities returned 66 pieces to Primrose Shipman and auctioned 33 pieces that she confirmed were not hers. Proceeds of the auction went to Tameside Victim Support.[49][50] The only piece returned to a murdered patient's family was a platinum diamond ring, for which the family provided a photograph as proof of ownership.

A memorial garden to Shipman's victims, called the Garden of Tranquillity, opened in Hyde Park, Hyde on 30 July 2005.[51]

As of early 2009, families of over 200 of the victims of Shipman were still seeking compensation for the loss of their relatives.[52] In September 2009, authorities announced that letters Shipman wrote in prison would be sold at auction,[53] but following complaints from victims' relatives and the media, they withdrew the letters from the sale.[54]

Shipman effect

The Shipman case, and a series of recommendations in the Shipman Inquiry report, led to changes to standard medical procedures in Britain (now referred to as the "Shipman effect"). Many doctors reported changes in their dispensing practices, and a reluctance to risk over-prescribing pain medication may have led to under-prescribing.[55][56] Death certification practices were altered as well.[57] Perhaps the largest change was the movement from single-doctor general practices to multiple-doctor general practices. This was not a direct recommendation, but rather because the report stated that there was not enough safeguarding and monitoring of doctors' decisions.

The forms needed for a cremation in England and Wales have had their questions altered as a direct result of the Shipman case. For example, the person(s) organising the funeral must answer, 'Do you know or suspect that the death of the person who has died was violent or unnatural? Do you consider that there should be any further examination of the remains of the person who has died?[58]

In media

Harold and Fred (They Make Ladies Dead) was a 2001 strip cartoon in Viz, also featuring serial killer Fred West. Some relatives of Shipman's victims voiced anger at the cartoon.[59][60]

Harold Shipman: Doctor Death, an ITV television dramatisation of the case, was made in 2002; it starred James Bolam in the title role.[61] The case was referenced in an episode of the 2003 CBS television medical drama series Diagnosis: Unknown called "Deadly Medicine" (Season 2, Episode 17).[62] In his role as Jack Halford in the BBC One television series New Tricks during the 2010 episode "Where There's Smoke", James Bolam mentions Shipman in a lecture on serial killers. The British sitcom Gavin & Stacey made use of the surnames of known English serial killers including Shipman for some of the main characters.[63]

A documentary also titled Harold Shipman: Doctor Death, with new witness testimony about the serial killer, was shown by ITV as part of its Crime & Punishment strand on 26 April 2018.[64] The programme was criticised as offering "little new insight".[65]

The British band The Fall refer to Shipman in their song "What About Us?" on the 2005 album Fall Heads Roll. The lyrics of the song mention a "doctor giving out morphine" and the chorus includes singer Mark E. Smith and backing singers chanting in call and response, "What about us? (Shipman!)"

The third season Law & Order: Criminal Intent episode "D.A.W." was based on the Shipman murder case.

A play titled Beyond Belief – Scenes From the Shipman Inquiry, written by Dennis Woolf and directed by Chris Honer was performed at the Library Theatre, Manchester, 20 October – 22 November 2004. The script of the play comprised edited verbatim extracts from The Shipman Inquiry, spoken by actors playing the witnesses and lawyers at the inquiry.[66] This provided a "stark narrative" that focused on personal tragedies.[67]

See also

References

- "Shipman known as 'angel of death'". BBC News. BBC. 9 July 2001. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- "Harold Shipman". The Times. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "The Shipman Inquiry". The Shipman Inquiry. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- "Harold Shipman: The killer doctor". BBC News. 13 January 2004. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Shipman 'killed early in career'". BBC News. 27 January 2005.

- Stovold, James. "The Case of Dr. John Bodkin Adams". Strangerinblood.co.uk. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- Oliver, Mark (13 January 2004). "Portrait of a necrophiliac". The Guardian.

- Swan, Norman (29 July 2002). "Why Some Doctors Kill". The Health Report. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Kaplan, Robert M. (2009). Medical Murder: Disturbing Cases of Doctors Who Kill. Allen & Unwin. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-74175-610-4.

- Born to Kill?, Channel 5, 2 August 2012

- Herbert, Ian (14 January 2004). "How a humble GP perverted his medical skill to become Britain's most prolific mass killer". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- The Early Life of Harold Shipman

- "Harold Shipman: Timeline". BBC News. 18 July 2002. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Bunyan, Nigel (16 June 2001). "The Killing Fields of Harold Shipman". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Archived 22 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Shipman interview rebroadcast". BBC News. 8 February 2001. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Second Report — The Police Investigation of March 1998 (Cm 5853). The Shipman Inquiry. 14 July 2003. Archived from the original on 5 March 2005.

- "Shipman inquiry criticises police". BBC News. 14 July 2003. Retrieved 30 July 2005.

- "I feel guilty over Shipman killings". BBC. 30 September 2003. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- "The Shipman tapes I". BBC News. 31 January 2000. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "UK Doctor 'forged victim's medical history'". BBC News. 8 November 1999. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- Whittle, B and Richie, J. Prescription for Murder: The True Story of Dr. Harold Frederick Shipman. Little Brown (2000), pp. 348–9. ISBN 0751529982.

- Spiegelhalter, D. et al. Risk-adjusted sequential probability ratio tests: application to Bristol, Shipman and adult cardiac surgery. Int J Qual Health Care, vol. 15, pp. 7–13 (2003).

- "Shipman jailed for 15 murders". BBC News. 31 January 2000. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Frith, Maxine (11 February 2000). "GMC strikes Shipman off medical register". The Independent. London. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Shipman struck off". BBC News. 11 February 2000. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- The Shipman Inquiry — Sixth Report — Conclusions Archived 13 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Shipman's 'reckless' experiments". BBC News. 27 January 2005.

- Sweet, Corinne (16 January 2004). "He could do no wrong". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- Strangerinblood.co.uk Nigel Cox was convicted of attempted murder in 1992, in the death of Lillian Boyes.

- Kinnell, HG (2000). "Serial homicide by doctors: Shipman in perspective". BMJ. 321 (7276): 1594–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7276.1594. PMC 1119267. PMID 11124192.

- Stovold, James. "Strangerinblood.co.uk". Strangerinblood.co.uk. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- "Harold Shipman found dead in cell". BBC. 13 January 2004.

- "No mourning from Shipman families". BBC News. 13 January 2004.

- "Blunkett admits Shipman error". BBC News. 16 January 2004.

- Hattenstone, Simon (19 January 2004). "Is it the Sun that's gone bonkers?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "Shipman's death divides papers". BBC News. 14 January 2004. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Shipman leaves his wife £24,000". BBC News. 8 April 2004.

- "Shipman suicide 'not preventable'". BBC News. 25 August 2005. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Harold Shipman found dead in cell". BBC News. 13 January 2004. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "How many more did Shipman kill?". The Independent. London. 9 October 2001. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- "Shipman doctors deny misconduct". BBC News. 3 October 2005.

- "Shipman doctor 'not good enough'". BBC News. 11 October 2005.

- "Shipman report demands GMC reform". BBC News. 9 December 2004.

- "Theft fears over 'Shipman gems'". BBC News. 17 March 2005.

- "Twenty make Shipman jewels claims". BBC News. 15 April 2005.

- "Shipman's stolen gems found in his wife's jewellery box". The Guardian. 31 August 2005. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Shipman jewels not going to widow". BBC News. 24 May 2005.

- "Shipman stole victim's jewellery". BBC News. 31 August 2005.

- "Shipman's stolen gems found in his wife's jewellery box". The Guardian. London. 31 August 2005. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Garden tribute to Shipman victims". BBC News. 30 July 2005.

- "Alexander Harris, the law firm who represented families of victims of Allitt and Shipman". Alexander Harris. 25 August 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2006.

- "Shipman prison letters to be sold". BBC News. BBC. 27 September 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Shipman letters removed from sale". BBC News. BBC. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "'Shipman effect' harms pain care". BBC. BBC. 7 August 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Queiro, Alicia (1 December 2014). "Shipman effect: How a serial killer changed medical practice forever". BBC. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Consultation Paper on Death Certification, Burial and Cremation". Scottish Government. 27 January 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/697075/cremation-form-1-app-for-cremation-of-body.pdf

- Garrett, Jade (1 February 2001). "'Viz' pushes taste to its limits with Shipman cartoon". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- "Anger at Shipman Cartoon". BBC News. 1 February 2001. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- Roger Bamford (Director) (2002). Harold Shipman: Doctor Death (Television drama).

- Greg Francis (Director) (2003). Diagnosis: Unknown: Deadly Medicine (Television series).

- "Cardiff confidential: Saying farewell to Gavin & Stacey". The Independent. 21 November 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "Harold Shipman: Doctor Death". ITV Press Centre. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- O'Donovan, Gerard (26 April 2018). "Harold Shipman: Doctor Death, review: 20 years on, this documentary offered little new insight". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- "Play exposes legacy of Shipman horror". Manchester Evening News. 22 October 2004. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Rushforth, Bruno (4 November 2004). "Beyond Belief: Scenes from the Shipman Inquiry". BMJ. 329 (7474): 1109. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7474.1109. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 526136.