Anti-corruption

Anti-corruption (anticorruption) comprise activities that oppose or inhibit corruption. Just as corruption takes many forms, anti-corruption efforts vary in scope and in strategy. A general distinction between preventive and reactive measures is sometimes drawn. In such framework, investigative authorities and their attempts to unveil corrupt practices would be considered reactive, while education on the negative impact of corruption, or firm-internal compliance programs are classified as the former.

| Political corruption | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | ||||||||||||

| Corruption by country | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

History

Early history

The code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BC), the Great Edict of Horemheb (c. 1300 BC), and the Arthasastra (2nd century BC)[1] are among the earliest written proofs of anti-corruption efforts. All of those early texts are condemning bribes in order to influence the decision by civil servants, especially in the judicial sector.[2] During the time of the Roman empire corruption was also inhibited, e.g. by a decree issued by emperor Constantine in 331.[3]

In ancient times, moral principles based on religious beliefs were common, as several major religions, such as Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Sikhism, and Taoism condemn corrupt conduct in their respective religious texts.[4] The described legal and moral stances were exclusively addressing bribery but were not concerned with other aspects that are considered corruption in the 21st century. Embezzlement, cronyism, nepotism, and other strategies of gaining public assets by office holders were not yet constructed as unlawfully or immoral, as positions of power were regarded a personal possession rather than an entrusted function. With the popularization of the concept of public interest and the development of a professional bureaucracy in the 19th century offices became perceived as trusteeships instead of property of the office holder, leading to legislation against and a negative perception of those additional forms of corruption.[5] Especially in diplomacy and for international trade purposes, corruption remained a generally accepted phenomenon of the political and economic life throughout the 19th and big parts of the 20th century.[6]

In contemporary society

In the 1990s corruption was increasingly perceived to have a negative impact on economy, democracy, and the rule of law, as was pointed out by Kofi Annan.[7] Those effects claimed by Annan could be proven by a variety of empirical studies, as reported by Juli Bacio Terracino.[8] The increased awareness of corruption was widespread and shared across professional, political, and geographical borders. While an international effort against corruption seemed to be unrealistic during the Cold War, a new discussion on the global impact of corruption became possible, leading to an official condemnation of corruption by governments, companies, and various other stakeholders.[9] The 1990s additionally saw an increase in press freedom, the activism of civil societies, and global communication through an improved communication infrastructure, which paved the way to a more thorough understanding of the global prevalence and negative impact of corruption.[10] In consequence to those developments, international non-governmental organizations (e.g. Transparency International) and inter-governmental organizations and initiatives (e.g. the OECD Working group on bribery) were founded to overcome corruption.[11]

Since the 2000s, the discourse became broader in scope. It became more common to refer to corruption as a violation of human rights, which was also discussed by the responsible international bodies.[12] Besides attempting to find a fitting description for corruption, the integration of corruption into a human rights-framework was also motivated by underlining the importance of corruption and educating people on its costs.[13]

Legal framework

In national and in international legislation, there are laws interpreted as directed against corruption. The laws can stem from resolutions of international organizations, which are implemented by the national governments, who are ratifying those resolutions or be directly be issued by the respective national legislative.

Laws against corruption are motivated by similar reasons that are generally motivating the existence of criminal law, as those laws are thought to, on the one hand, bring justice by holding individuals accountable for their wrongdoing, justice can be achieved by sanctioning those corrupted individuals, and potential criminals are deterred by having the consequences of their potential actions demonstrated to them.[14]

International law

Approaching the fight against corruption in an international setting is often seen as preferential over addressing it exclusively in the context of the nation state. The reasons for such preference are multidimensional, ranging from the necessary international cooperation for tracing international corruption scandals,[15] to the binding nature of international treaties, and the loss in relative competitiveness by outlawing an activity that remains legal in other countries.

OECD

The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention was the first large scale convention targeting an aspect of corruption, when it came in 1999 into force. Ratifying the convention obliges governments to implement it, which is monitored by the OECD Working Group on Bribery. The convention states that it shall be illegal bribing foreign public officials. The convention is currently signed by 43 countries. The scope of the Convention is very limited, as it is only concerned with active bribing. It is hence more reduced than other treaties on restricting corruption, to increase – as the working group's chairman Mark Pieth explained – the influence on its specific target.[16] Empirical research by Nathan Jensen and Edmund Malesky suggests that companies based in countries that ratified the convention, are less likely to pay bribes abroad.[17] The results are not exclusively explainable by the regulatory mechanisms and potential sanctions triggered through this process but are equally influenced by less formal mechanisms, e.g. the peer reviews by officials from other signatories and the potentially resulting influences on the respective country's image.[18] Groups like TI, however, also questioned whether the results of the process are sufficient, especially as a significant number of countries is not actively prosecuting cases of bribery.[19]

United Nations

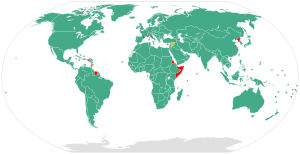

- Ratifiers

- Signatories

- Not signed

- Others

20 years before the OECD convention was ratified, the United Nations discussed a draft for a convention on corruption. The draft on an international agreement on illicit payments proposed in 1979[20] by the United Nations Economic and Social Council did not gain traction in the General Assembly, and was not pursued further.[21] When the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) presented its draft of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in 2003, it proved more successful. UNCAC was ratified in 2003 and became effective in 2005. It constitutes an international treaty, currently signed by 186 partners, including 182 member states of the United Nations and four non-state signatories. UNCAC has a broader scope than the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, as it does not exclusively focus on public officials but includes inter alia corruption in the private sector and non-bribery corruption, like e.g. money laundering and abuse of power. UNCAC also specifies a variety of mechanisms to combat corruption, e.g. international cooperation in detecting and prosecuting corruption, the cancellation of permits, when connected to corrupt behavior, and the protection of whistleblowers. The implementation of UNCAC is monitored by the International Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (IAACA)

International organizations

International Anti-Corruption Court

Mark Lawrence Wolf floated in 2012 the idea to launch an International Anti-Corruption Court, as either a part of the already existing International Criminal Court, or as an equivalent to it. The suggestion was widely discussed and endorsed by a variety of NGOs including Global Organization of Parliamentarians Against Corruption (GOPAC), Global Witness, Human Rights Watch, the Integrity Initiatives International (III), and TI.[22] An implementation of the concept is currently not scheduled by any organizations with the authority of conducting such step.

Existing international organizations

In 2011, the International Anti-Corruption Academy was created as an intergovernmental organization by treaty[23] to teach on anti-corruption topics.[24]

Many other intergovernmental organizations are working on the reduction of corruption without issuing conventions binding for its members after ratification. Organizations that are active in this field include, but are not limited to, the World Bank (such as through its Independent Evaluation Group), the International Monetary Fund (IMF),[25] and regional organizations like the Andean Community (within the framework of the Plan Andino de Lucha contra la Corrupción).[26]

Regulations by continental organizations

Americas

The first convention adopted against corruption by a regional organization was the Organization of American States' (OAS) Inter-American Convention Against Corruption (IACAC). The Convention, which targeted both active and passive bribing, came into force in 1997. It is currently ratified by all 34 active OAS-Member States.[27][lower-alpha 1]

Europe

In 1997 the European Union (EU) adopted the EU Convention against corruption involving officials, which makes it illegal to engage in corrupt activities with officials from the European Union's administrative staff, or with officials from any member state of the EU. It forces the signatories to outlaw both active and passive bribing which involves any aforementioned official. Liability for unlawful actions is extend to the heads of those entities, whose agents were bribing officials.[28]

European states also ratified the Council of Europe's Criminal and Civil Law Convention on Corruption, which were adopted in 1999. The former was an addition extended by passing the Additional Protocol to the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption. The two conventions on criminal law were signed by Belarus and all Council of Europe members, with the exception of Estonia, which abstains from the Additional Protocol.[lower-alpha 2] The Criminal Law Convention is currently by 48 States, while the Additional Protocol is signed by 44 countries.[29][30] Both conventions are aiming at the protection of judicial authorities against the negative impact of corruption.[31]

The convention on Civil Law is currently ratified by 35 countries, all of which are, with the exception of Belarus, members of the Council of Europe.[32] As the name implies, it requires the States Parties to provide remedies for individuals materially harmed by corruption. The individual who was negatively impacted by an act of corruption is entitled to rely on laws to receive compensation from the culprit or the entity represented by the culprit, explicitly including the possibility of compensation from the state, if the corrupt deed was perpetrated by an official.[33] The anti-corruption efforts by the Council of Europe are supervised and supported by the Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) as its main monitoring organization. Membership to GRECO is open to all countries worldwide and is not conditional on membership at CoE.

Africa

Since its launch in 2003, the African Union's Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption was ratified by 38 States Parties.[34] It represents the consensus of the signatories on minimal standards for combating corruption. The resolution was criticized in the Journal of African Law for disregarding other aspects of the rule of law, like e.g. data protection and the presumption of innocence.[35]

National law

While bribing domestic officials was criminalized in most countries even before the ratification of international conventions and treaties,[36] many national law systems did not recognize bribing foreign officials, or more sophisticated methods of corruption as illegal. Only after ratifying and implementing above mentioned conventions the illegal character of those offenses was fully recognized.[37] Where legislation existed prior to the ratification of the OECD convention, the implementation resulted in an increased compliance with the legal framework.[38]

Corruption is often addressed by specialized investigative or prosecution authorities, often labelled as anti-corruption agencies (ACA) that are tasked with varying duties, subject to varying degrees of independence from the respective government, regulations and powers, depending on their role in the architecture of the respective national law enforcement system. One of the earliest precursors of such agencies is the anti-corruption commission of New York City, which was established in 1873.[39] A surge in the numbers of national ACAs can be noted in the last decade of the 20th and the first decade of the 21st century.[40]

Brazil

Brazil's Anti-Corruption Act (officially "Law No. 12,846" and commonly known as the Clean Company Act") was enacted in 2014 to target corrupt corrupt practices among business entities doing business in Brazil. It defines civil and administrative penalties, and provides the possibility of reductions in penalties for cooperation with law enforcement under a written leniency agreement signed and agreed to between the business and the government. This had major implications in Operation Car Wash, and resulted in major agreements such as the Odebrecht–Car Wash plea bargain agreements and the recovery of billions of dollars in fines.[41]

United States

Already at the foundation of the United States discussions on the possibility of preventing corruption were held, leading to increased awareness for corruption's threads. Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution can be seen as an early anti-corruption law, as it outlawed the acceptance of gifts and other favors from foreign governments and their representatives. Zephyr Teachout argued that giving and receiving presents held an important role in diplomacy but were often seen as potentially dangerous to a politician's integrity.[42] Other early attempts to oppose corruption by law were enacted after the end of World War II. The Bribery and Conflict of Interest Act of 1962 for example regulates the sanctions for bribing national officials, respectively the acceptance of bribes by national officials, and the abuse of power for their personal interest. The Hobbs Act of 1946 is another law frequently applied by US-American prosecutors in anti-corruption cases. Prosecutors are using the act by arguing that the acceptance of benefits for official acts qualifies as an offence against the act. Less frequently laws to prosecute corruption through auxiliary criminal activities include the Mail Fraud Statute and the False Statements Accountability Act.[43]

In 1977, the United States of America adopted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which criminalized corrupt interactions with foreign officials. Since its implementation, the law served to prosecute domestic and foreign companies, who bribed officials outside of the United States. As no other country implemented a similar law up to the 1990s, US-American companies faced disadvantages for their global operations. In addition to the legal status of corruption abroad, many countries also treated bribes as tax-deductible. Through applying the law to companies with ties to the United States and by working on global conventions against foreign bribery, the government of the US tried to reduce the negative impact of FCPA on US-American companies.[44]

Alongside the FCPA, additional laws were implement that are directly influencing anti-corruption activities. Section 922 of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act for instance extents the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 by a new Section 21F that protects whistleblowers from retaliation and grants them financial awards them when collaborating with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Conway-Hatcher et al. (2013) attributed an increase the number of whistleblowers, who are reporting to SEC, inter alia on corruption incidents to the provision.[45]

The TI's last report on enforcement of the OECD Convention against bribery published in 2014 concluded that the United States are complying with the convention.[46]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom was a founding member of the OECD working group on bribery and ratified the Anti-Bribery Convention, but faced significant problems in complying to its findings and the convention.[47] It was severely affected by the Al-Yamamah arms deal, in which the British company BAE Systems faced allegations of having bribed members of the Saudi royal family to facilitate an arms deal. British prosecution of BAE Systems was stopped after an intervention by than Prime Minister Tony Blair, which caused the OECD working group to criticize the British anti-corruption laws and investigations.

The UK Bribery Act of 2010 came into force on July 1, 2011, and replaced all former bribery-related laws in the United Kingdom. It is targeting bribery and receiving bribes, both towards national and foreign public officials. Furthermore, it is assigning responsibility to organizations whose employees are engaging in bribing and hence obliges companies to enforce compliance-mechanisms to avoid bribing on their behalf. The Bribery Act goes in many points beyond the US-American FCPA, as it also criminalizes facilitation payments and private sector corruption inter alia.[48] Heimann and Pieth are arguing that British policy makers supported the Bribery Act to overcome the damage in reputation caused by the Al-Yamamah deal.[49] Sappho Xenakis and Kalin Ivanov on the other hand claim that the negative impact on the UK's reputation was very limited.[50]

Transparency International stated in 2014 that the United Kingdom fully complied to the OECD Convention against Bribery.[46]

Canada

Canada remained one of the last signatories of the OECD-convention on bribery that did not implement its national laws against bribes for foreign officials.[51] While the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act (CFPOA) was passed in 1999, it was often not used to prosecute foreign bribery by Canadian companies, as the bill had a provision that the act of bribery had to have a "real and substantial link" with Canada. Such provision was canceled in 2013 by the Bill S-14 (also called Fighting Foreign Corruption Act). Additionally, Bill S-14 banned facilitation payments and increased the possible punishment for violating the CFPOA.[52] An increase in the maximum prison sentence for bribery to 14 years was one of the increases in sanctioning.[53] According to TI's report from 2014, Canada is moderately enforcing the OECD Convention against bribery.[46]

China

In the wake of economic liberalization, corruption increased in China because anti-corruption laws were insufficiently applied.[54] The anti-corruption campaign that started in 2012, however, changed the relation towards corruption. This campaign led to increased press coverage of the topic and a sharp increase in court cases dedicated to the offense. The campaign was primarily led by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), an internal body of the Communist Party and secondarily by the People's Procuratorate.[55] CCDI cooperated with investigative authorities in several ways, such as passing incriminating material detected by its internal investigation, to prosecutors.

The underlying legal regulations for the campaign is rooted in provisions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law and the criminal law.

Japan

After signing the OECD-Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials[56], Japan implemented the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) to comply with the convention. The law states that it is illegal to bribe foreign public officials. The individual who was offering the bribes and the company on whose behalf the bribes were offered may face negative consequences. The Company Act also enables the punishment of senior management if the payment was made possible by their negligence. Transparency International criticized Japan in 2014 for not enforcing the law, hence only complying to the convention on paper and providing no consequences to offenders.[46] Nevertheless, a study conducted by Jensen and Malesky in 2017 provides empirical evidence that Japanese companies are less involved in bribery than companies based in other Asian countries that did not sign the convention.[17]

Governmental anti-corruption beyond the law

Prevention of corruption/anti-corruption

Values education is believed to be a possible tool to teach about the negative effects of corruption and to create resilience against acting in a corrupt manner, when the possibility of doing so arises.[57] Another stream of thought on corruption prevention is connected to the economist Robert Klitgaard, who developed an economic theory of corruption that explains the occurrence of corrupt behavior by producing higher gains than the assumed punishment it might provoke. Klitgaard accordingly argues for approaching this rational by increasing the costs of corruption for those involved by making fines more likely and more severe.

Good governance

As corruption incidences often happen in the interaction between representatives of private sector companies and public officials, a meaningful step against corruption can be taken inside of public administrations. The concept of good governance can accordingly be applied to increase the integrity of administrations, decreasing hence the likelihood that officials will agree on engaging in corrupt behavior.[58] Transparency is one aspect of good governance.[59] Transparency initiatives can help to detect corruption and hold corrupt officials and politicians accountable.[60]

Another aspect of good governance as a tool to combat corruption lies in the creation of trust towards state institutions. Gong Ting and Xiao Hanyu for instance argue that citizens, who have a positive perception of state institutions are more likely to report corruption related incidents than those, who espress lower levels of trust.[61]

Sanctions

Even though sanctions seem to be underwritten by a legal framework, their application is often lying outside of a state-sponsored legal system, as they are frequently applied by multilateral development banks (MDB), state agencies, and other organizations, who are implementing those sanctions not through applying laws, but by relying on their internal bylaws. World Bank, even though reluctant in the 20th century to use sanctions,[62] turned into a major source of this specific kind of applying anti-corruption measures.[63] the involved MDBs are typically applying an administrative process that includes judicial elements, when a suspicion about corruption in regard to the granted projects surfaces. In case of identifying a sanctionable behavior, the respective authority can issue a debarment or milder forms, e.g. mandatory monitoring of the business conduct or the payment of fines.[64]

Public sector procurement

Excluding companies with a track record of corruption from bidding for contracts, is another form of sanctioning that can be applied by procurement agencies to ensure compliance to external and internal anti-corruption rules.[65] This aspect is of specific importance, as public procurement is both in volume and frequency especially vulnerable for corruption. In addition to setting incentives for companies to comply with anti-corruption standards by threatening their exclusion from future contracts, the internal compliance to anti-corruption rules by the procurement agency has central importance. Such step should according to anti-corruption scholars Adam Graycar and Tim Prenzler include precisely and unambiguously worded rules, a functional protection and support of whistleblowers, and a system that notifies supervisors on an early base about potential dangers of conflicts of interest or corruption-related incidents.[66]

Civil society

Michael Johnston, among others, argued that non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and the media can have an efficient influence on the level of corruption.[67] More over, Bertot et al. (2010) extended the list of potentially involved agents of civil society by introducing the notion of decentralized, non-formally organized anti-corruption activism through social media channels.[68]

Taking into consideration that precise and comprehensive definitions of corrupt actions are lacking, the legal perspective is structurally incapable of efficiently ruling out corruption. Combined with a significant variety in national laws, frequently changing regulations, and ambiguously worded laws, it is argued that non-state actors are needed to complement the fight against corruption and structure it in a more holistic way.[39]

Ensuring transparency

An example for a more inclusive approach to combating corruption that goes beyond the framework set by lawmakers and the foremost role taken by representatives of the civil society is the monitoring of governments, politicians, public officials, and others to increase transparency. Other means to this end might include pressure campaigns against certain organizations, institutions, or companies.[69] Investigative journalism is another way of identifying potentially corrupt dealings by officials. Such monitoring is often combined with reporting about it, in order to create publicity for the observed misbehavior. Those mechanisms are hence increasing the price of corrupt acts, by making them public and negatively impacting the image of the involved official. One example for such strategy of combating corruption by exposing corrupt individuals is the Albanian television show Fiks Fare that repeatedly reported on corruption by airing segments filmed with hidden cameras, in which officials are accepting bribes.[70]

Education on corruption

Another sphere for engagement of civil society is the prevention by educating about the negative consequences of corruption and a strengthening of ethical values opposing corruption. Framing corruption as a moral issue used to be the predominant way of fighting it but lost importance in the 20th century as other approaches became more influential.[71][72] The biggest organization in the field of civil societal opposition towards corruption is the globally active NGO Transparency International (TI).[73] NGOs are also providing material to educate practitioners on anti-corruption. Examples for such publications are the rules and suggestions provided by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), the World Economic Forum (WEF), and TI.[74] Persistent work by civil societal organizations can also go beyond establishing a knowledge about the negative impact of corruption and serve as way to build up political will to prosecute corruption and engage in counter-corruption measures.[75]

Non-state actors in the field of asset recovery

One prominent field of activism for non-state actors (NSAs) is the area of international asset recovery, which describes the activity of returning property to its legitimate owners after it was illegally acquired through corrupt actions. The process describes the whole procedure from gathering information on the criminal offence that initiated the transfer of assets, over their confiscation to their return. While recovery is mandated by UNCAC, it is not an activity singularity conducted by governments but attracts actors with different backgrounds, including academia, the media, CSOs, and other non state actors. In this field of anti-corruption activism, representatives of the civil society are often taking a different stance than in other areas, as they are regularly consulted for assisting administrations with their respective expertise and are hence enabling state actions. Such strong role of NSAs was also recognized by UNCAC's States Parties.[76]

Corporate anti-corruption approaches

Compliance

Instead of relying purely on deterrence, as suggested by Robert Klitgaard (see section on prevention), economists are pursuing the implementation of incentive structures that reward compliance and punish the non-fulfillment of compliance rules. By aligning the self-interest of the agent with the societal interest of avoiding corruption, a reduction in corruption can thus be achieved.[77]

The field of compliance can generally be perceived as an internalization of external laws in order to avoid their fines. The adoption of laws like the FCPA and the UK Bribery Act of 2010[78] strengthened the importance of concepts like compliance, as fines for corrupt behavior became more likely and there was a financial increase on these fines. When a company is sued because its employers engaged in corruption, a well-established compliance system can serve as proof that the organization attempted to avoid those acts of corruption. Accordingly, fines can be reduced and this incentivizes the implementation of an efficient compliance system.[48] In 2012, the US-authorities decided not to prosecute Morgan Stanley in a case of bribery in China under FCPA-provisions due to its compliance program.[53] This case demonstrates the relevance of the compliance approach.

Collective action

Anti-corruption collective action is a form of collective action with the aim of combatting corruption and bribery risks in public procurement. It is a collaborative anti-corruption activity that brings together representatives of the private sector, public sector and civil society. The idea stems from the academic analysis of the prisoner's dilemma in game theory and focuses on establishing rule-abiding practices that benefit every stakeholder, even if unilaterally each stakeholder might have an incentive to circumvent the specific anti-corruption rules. Transparency International first floated a predecessor to modern collective action initiatives in the 1990s with its concept of the Island of Integrity, now known as an integrity pact.[79] According to Transparency International, "collective action is necessary where a problem cannot be solved by individual actors" and therefore requires stakeholders to build trust and share information and resources.[80]

The World Bank Institute states that collective action "increases the impact and credibility of individual action, brings vulnerable individual players into an alliance of like-minded organizations and levels the playing field between competitors.[81]

Anti-corruption collective action initiatives are varied in type, purpose and stakeholders but are usually targeted at the supply side of bribery.[82] They often take the form of collectively agreed anti-corruption declarations or standard-setting initiatives such as an industry code of conduct. A prominent example is the Wolfsberg Group and in particular its Anti-Money Laundering Principles for Private Banking and Anti-Corruption Guidance, requiring the member banks to adhere to several principles directed against money laundering and corruption. The mechanism is designed to protect individual banks from any negative consequences of complying with the strict rules by collectively enforcing those regulations. The Wolfsberg Group in addition serves as a back-channel for communication between the compliance officers of the participating banks.[83] The World Economic Forum's initiatives against corruption can also be seen in this framework.[84] Other initiatives in the field of collective action include the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), Construction Sector Transparency Initiative/Infrastructure Transparency Initiative (CoST) and International Forum on Business Ethical Conduct (IFBEC).[85] Collective action is included in the national anti-corruption statements of the UK[86], France[87] and Ghana[88], delivered at the International Anti-Corruption Conference 2018.

The B20 policy interventions are another form of engaging in the anti-corruption discourse, as B20 members are attempting to support the G20 by offering their insights as business leaders, including in regard to strengthening anti-corruption policies, e.g. transparency in government procurement or more comprehensive anti-corruption laws.[89] In 2013, the B20 mandated the Basel Institute on Governance to develop and maintain the B20 Collective Action Hub, an online platform for anti-corruption collective action tools and resources including a database of collective action initiatives around the world. The B20 Collective Action Hub is managed by the Basel Institute's International Centre for Collective Action (ICCA) in partnership with the UN Global Compact.

Another tangible outcome of the B20 meetings was the discussion (and implementation as a test case in Colombia) of the High Level Reporting Mechanism (HLRM), which aims to implement a form of ombudsman office in a high-level government position for companies to report possible bribery or corruption issues in public procurement tenders.[90] As well as Colombia, the HLRM concept has been implemented in different ways in Argentina, Ukraine and Panama.[91]

Implementation

Sylvie Bleker-van Eyk from VU University Amsterdam sees value in the implementation of strong compliance departments in the respective company.[48] Fritz Heimann and Mark Pieth are described the environment where those departments are working, as being in a best cased monitored from outside experts.[92] Another measure that – according to Heimann and Pieth – supports the work of compliance officers is when the company is joining collective action initiatives.[93] Instruments like ethical codes can serve as underlying documents to promote support for anti-corrupt corporate policies. Seumas Miller et al. (2005) also stress the process of reaching the aspired result, which should include an open discussion among the employees of a company, in order to implement steps that are approved by consent inside of the company.[94] Such shift in culture can be implemented through and accompanied by exemplary behavior by top management, regularly conducted training programs on anti-corruption and a constant monitoring of the development in those sections.[95]

In culture

International Anti-Corruption Day has been annually observed on December 9 since the United Nations established it in 2003 to underline the importance of anti-corruption and provide visible sign for anti-corruption campaigns.[96]

See also

Notes

- Cuba was suspended from the OAS from 1962 to 2009. After the ban on Cuba's participation was lifted in 2009, the country elected not to participate. See: Cuban relations with the Organization of American States.

- The Czech Republic, Italy and the Russian Federation signed the Protocol but did so far not ratify it.[29][30]

References

- Olivelle, Patrick (2013). King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-19-989182-5.

- Bacio Terracino (2012), p. 28

- Noonan, John T. (1984). Bribes. New York: Macmillan. p. 90. ISBN 0-02-922880-8.

- Bacio Terracino (2012), p. 29

- Bacio Terracino (2012), p. 30

- Confronting Corruption, p. 9

- Peters, Anne (2011). "Preface". In Thelesklaf, Daniel; Gomes Pereira, Pedro (eds.). Non-State Actors in Asset Recovery. Peter Lang. pp. vii–ix. ISBN 978-3-0343-1073-4.

- Bacio Terracino (2012), pp.31-34

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 12 et seq.

- Mccoy, Jennifer L.; Heckel, Heather (2001). "The Emergence of a Global Anti-corruption Norm". International Politics. 38 (1): 65–90. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ip.8892613.

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 13-14

- Boersma, Martine (2012). Corruption: A Violation of Human Rights and a Crime Under International Law?. Intersentia. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-78068-105-4.

- Sepúlveda Carmona, Magdalenda; Bacio-Terracino, Julio (2010). "Chapter III. Corruption and Human Rights: Making the Connection". In Boersma, Martine; Nelen, Hans (eds.). Corruption & Human Rights: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Intersentia. pp. 25–50. ISBN 9789400000858.

- Miller, Seumas; Roberst, Peter; Spence, Edward (2005). Corruption and Anti-Corruption: An Applied Philosophical Approach. Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-13-061795-8. LCCN 2004002505.

- Stukalo, Alexey (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. pp. 208 et seq.

- International Anti-Corruption Norms, pp. 59 et seq.

- Jensen, Nathan M.; Malesky, Edmund J. (2017). "Nonstate Actors and Compliance with International Agreements: An Empirical Analysis of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention". International Organization. 72 (1): 33–69. doi:10.1017/S0020818317000443.

- International Anti-Corruption Norms, Chapter 2, pp. 59–95

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 94–95

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2001): "Illicit Payments", UNCTAD Series on International investment agreements. p. 24

- International Anti-Corruption Norms, p. 64

- Magistad, Mary Kay (April 21, 2017). "Disrupting the Kleptocrat's Playbook, one investigative report at a time". Public Radio International. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Schermers, Henry G.; Blokker, Niels M. (2011). International institutional law : unity within diversity (5th ed.). Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 30. ISBN 9789004187962. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- Fletcher, Clare; Herrmann, Daniela (2012). The internationalisation of corruption : scale, impact and countermeasures. Gower. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4094-1129-1.

- Thomson, Alistair (May 18, 2017). "Beheading the Hydra: How the IMF Fights Corruption". Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- "Bolivia asume la presidencia del Parlamento Andino por un año". Opinión (in Spanish). August 9, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- "List of signatories of IACAC". Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- "European Anti-Corruption Conventions". GAN Integrity. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- "List of signatories of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption". Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- "List of signatories of the Additional Protocol to the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption". Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- Stukalo, Alexey (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. p. 16.

- "List of signatories of the Civil Law Convention on Corruption". Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- Stukalo, Alexey (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. pp. 11 et seq.

- "List of signatories of the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- Schroth, Peter W. (2005). "The African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption". Journal of African Law. 49 (1): 24–38. doi:10.1017/S0021855305000033. JSTOR 27607931.

- OECD Bribery Awareness Handbook for Tax Examiners (PDF). OECD. 2009. p. 15.

- Pacini, Carl; Swingen, Judyth A.; Rogers, Hudson (2002). "The Role of the OECD and EU Conventions in Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials". Journal of Business Ethics. 37 (4): 385–405. doi:10.1023/A:1015235806969.

- Cuervo-Cazurra, Alvaro (2008). "The effectiveness of laws against bribery abroad". Journal of International Business Studies. 39 (4): 634–651. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400372.

- Graycar, Adam; Prenzler, Tim (2013). "Chapter 4: The Architecture of Corruption Control". Understanding and Preventing Corruption. Crime Prevention and Security Management. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 50–69. doi:10.1057/9781137335098. ISBN 978-1-137-33508-1.

- Heilbrunn, John R. (2004). "Anti-Corruption Commissions Panacea or Real Medicine to Fight Corruption?" (PDF). World Bank Institute. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- Bedinelli, Talita (December 21, 2016). "Odebrecht e Braskem pagarão a maior multa por corrupção da história" [Odebrecht and Braskem to pay the highest fine for corruption in history]. El País (in Portuguese). Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- Teachout, Zephyr (2014). Corruption in America. Harvard University Press. pp. 17 et seq. ISBN 978-0-674-05040-2.

- Miller, Seumas; Roberst, Peter; Spence, Edward (2005). Corruption and Anti-Corruption: An Applied Philosophical Approach. Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-13-061795-8. LCCN 2004002505.

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 72 et seq.

- Conway-Hatcher, Amy; Griggs, Linda; Klein, Benjamin (2013). "Chapter 12: How whistleblowing may pay under the U.S. Dodd-Frank Act: implications and best practices for multinational companies". In Del Debbio, Alessandra; Carneiro Maeda, Bruno; da Silva Ayres, Carlos Henrique (eds.). Temas De Anticorrupção e Compliance. Elsevier. pp. 251–267. ISBN 9788535269284.

- Vogl, Frank (2014). "Trade Trumps Anti-Corruption". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- International Anti-Corruption Norms, p. 61

- Bleker-van Eyk, Sylvie C. (2017). "Chapter 17: Anti-Bribery & Corruption". In Bleker-van Eyk, Sylvie C.; Houben, Raf A. M. (eds.). Handbook of Compliance & Integrity Management. Kluwer Law International. pp. 311–324. ISBN 9789041188199.

- Confronting Corruption, p. 93

- Xenakis, Sappho; Ivanov, Kalin (2016). "Does Hypocrisy Matter? National Reputational Damage and British Anti-Corruption Mentoring in the Balkans" (PDF). Critical Criminology. 25 (3): 433–452. doi:10.1007/s10612-016-9345-4. ISSN 1205-8629.

- Confronting Corruption, p. 98

- Ramsay, Christopher J; Wilson, Clark (January 2018). "The Anti-Bribery and Anti-Corruption Review – Edition 6: CANADA". The Law Reviews. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- Aiolfi, Gemma (2014). "Mitigating the Risks of Corruption Through Collective Action". In Brodowski, Dominik; Espinoza de los Monteros de la Parra, Manuel; Tiedemann, Karl; Vogl, Joachim (eds.). Regulating Corporate Criminal Liability. Springer. pp. 125–134. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05993-8_11. ISBN 978-3-319-05992-1.

- Gong, Ting; Zhou, Na (2015). "Corruption and marketization". Regulation & Governance. 9: 63–76. doi:10.1111/rego.12054.

- Chen, Lyric (2017). "Who Enforces China's Anti-corruption Laws? Recent Reforms of China's Criminal Prosecution Agencies and the Chinese Communist Party's Quest for Control". Loyola of Los Angeles International & Comparative Law Review. 40 (2): 139–166. ISSN 1533-5860.

- "Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions" (PDF). OECD. 2011.

- Confronting Corruption, p. 217

- Stukalo, Alexey (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. pp. 55 et seq.

- Rubbra, Alice (April 19, 2017). "What makes good governance? #2 in series: Why transparency in governance is so important". R:Ed. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- Schnell, Sabina (2018). "Cheap talk or incredible commitment? (Mis)calculating transparency and anti‐corruption". Governance. 31 (3): 415–430. doi:10.1111/gove.12298. ISSN 0952-1895.

- Gong, Ting; Xiao, Hanyu (2017). "Socially Embedded Anti-Corruption Governance: Evidence from Hong Kong". Public Administration & Development. 37 (3): 176–190. doi:10.1002/pad.1798. ISSN 0271-2075.

- Confronting Corruption pp.49 et seq.

- Confronting Corruption, p. 214

- Confronting Corruption pp. 213 et seq.

- Confronting Corruption, p. 223

- Graycar, Adam; Prenzler, Tim (2013). "Chapter 7: Preventing Corruption in Public Sector Procurement". Understanding and Preventing Corruption. Crime Prevention and Security Management. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 100–113. doi:10.1057/9781137335098. ISBN 978-1-137-33508-1.

- Johnston, Michael, ed. (2005). Civil Society and Corruption: Mobilizing for Reform. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-3125-9.

- Bertot, John C.; Jaeger, Paul T.; Gimes, Justin M. (2010). "Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies". Government Information Quarterly. 27 (3): 264–271. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2010.03.001.

- Büthe, Tim (2004). "Governance through private authority? Non-state actors in world politics" (PDF). Journal of International Affairs. 58 (1): 281–290.

- Musaraj, Smoki (2018). "Corruption, Right On! Hidden Cameras, Cynical Satire, and Banal Intimacies of Anti-corruption". Current Anthropology. 59: 105–116. doi:10.1086/696162. ISSN 0011-3204.

- Bardhan, Pranab (1997). "Corruption and Development: A Review of Issues". Journal of Economic Literature. 35 (3): 1320–1346. JSTOR 2729979.

- Bacio Terracino (2012), pp. 29-31

- Stukalo, Alexey (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. pp. 142 et seq.

- Confronting Corruption, p. 224

- Ayogu, Melvin (2011). "Non-state actors and value recovery: Ganging up political will". In Thelesklaf, Daniel; Gomes Pereira, Pedro (eds.). Non-State Actors in Asset Recovery. Peter Lang. pp. 93–108. ISBN 978-3-0343-1073-4.

- Gomes Pereira, Pedro; Roth, Anja; Attisso, Kodjo (2011). "A stronger role for non-state actors in the asset recovery process". In Thelesklaf, Daniel; Gomes Pereira, Pedro (eds.). Non-State Actors in Asset Recovery. Peter Lang. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3-0343-1073-4.

- Teichmann, Fabian Maximilian Johannes (2017). Anti-Bribery Compliance Incentives. Kassel University Press. pp. 102 et seq. ISBN 978-3-7376-5034-2.

- "Bribery Act 2010". www.legislation.gov.uk. Expert Participation. Retrieved October 7, 2018.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The Integrity Pact (PDF). Transparency International. 2016.

- Collective Action on Business Integrity. Transparency International. 2018.

- World Bank Institute: Fighting Corruption Through Collective Action

- B20 Collective Action Hub

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 225 et seq.

- OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. 2016. p. 155.

- Confronting Corruption pp.226-227

- Stukalo, Alexey (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. OSCE. pp. 155 et seq.

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 238-239

- HLRM case studies on the B20 Collective Action Hub

- Confronting Corruption p. 233

- Confronting Corruption, pp. 235 et seq.

- Miller, Seumas; Roberst, Peter; Spence, Edward (2005). Corruption and Anti-Corruption: An Applied Philosophical Approach. Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-13-061795-8. LCCN 2004002505.

- Confronting Corruption p. 232

- "Main page of the campaign for an International Anti-Corruption Academy". UNODC. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

Sources

- Bacio Terracino, Julio (2012). The international legal framework against corruption : states' obligations to prevent and repress corruption. Intersentia. ISBN 978-1-78068-092-7. OCLC 810879652.

- Rose, Cecily (2015). International Anti-Corruption Norms. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873721-6. OCLC 908334497.

- Stukalo, Alexey, ed. (2016). OSCE Handbook on Combating Corruption. Vienna: Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. ISBN 978-92-9234-192-3. OCLC 964654700.

- Heimann, Fritz; Pieth, Mark (2018) [2017]. Confronting Corruption. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-045833-1. OCLC 965154105.