Du Yuesheng

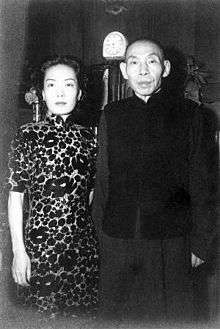

Du Yuesheng (22 August 1888 – 16 August 1951), also known by Dou Yu-Seng or Tu Yueh-sheng or Du Yueh-sheng, nicknamed "Big-Eared Du",[1] was a Chinese mob boss who spent much of his life in Shanghai. He was a key supporter of Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang in their battle against the Communists in the 1920s, and was a figure of some importance during the Second Sino-Japanese War. After the Chinese Civil War and the Kuomintang's retreat to Taiwan, Du went into exile in Hong Kong and remained there until his death in 1951.

Du Yuesheng | |

|---|---|

杜月笙 | |

| |

| Born | 22 August 1888 |

| Died | 16 August 1951 (aged 62) |

| Resting place | Du Yuesheng Cemetery, Shulin District, New Taipei City, Taiwan |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Occupation | Underworld Leader |

| Height | 5'10 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Du Yuesheng | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 杜月笙 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Du Yong | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 杜鏞 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 杜镛 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Du Yuesheng (original name) | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 杜月生 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Early life

Du was born in Gaoqiao, a small town east of Shanghai, during the reign of the Guangxu Emperor in the late Qing dynasty. His family moved to Shanghai in 1889, a year after his birth. By the time he reached nine years old, Du had lost his immediate family — his mother died in childbirth, his sister was sold into slavery, his father died, and his stepmother vanished — so he went back to Gaoqiao and lived with his grandmother. He returned to Shanghai in 1902 and worked at a fruit stall in the French Concession but was later fired for theft. He wandered around for some time before becoming a bodyguard in a brothel, where he became acquainted with the Green Gang. He joined the gang at the age of 16.

Rise to power

Du was soon introduced by a friend to Huang Jinrong, the highest-ranked Chinese detective in the French Concession Police (FCP) and one of Shanghai's most notorious gangsters. Huang's wife Lin Guisheng was a notable criminal in her own right, and she favoured the young Du. Even though Huang was not a member of the Green Gang, Du became Huang's gambling and opium enforcer. A stickler for fine clothing and women, Du was now cemented; he wore only Chinese silks, surrounded himself with White Russian bodyguards, and frequented the city's best nightclubs and sing-song houses. Du was also known for having a superstitious streak — he had three small monkey heads, specially imported from Hong Kong, sewn to his clothes at the small of his back.

Du's prestige led him to purchase a four-storey, Western-style mansion in the French Concession and have dozens of concubines, four legal wives and six sons, but his meteoric rise as Shanghai's best known mobster only came after Huang Jinrong's arrest in 1924 by the Shanghai Garrison police [2] for his public beating of Lu Xiaojia, son of the then Shanghai-ruling warlord Lu Yongxiang. It required Du's diplomacy and finances to save his mentor, who after the release stood down almost immediately, turning his criminal empire over to Du. Now known as the "zongshi" (宗師) or "grandmaster" of the criminal underworld, Du controlled gambling dens, prostitution and protection rackets, as well as setting up a number of legitimate companies — including Shanghai's largest shipping corporation and two banks. With the tacit support of the police and colonial government, he also now ran the French Concession's opium trade, and became heavily addicted to his own drug.

Alliance with the Kuomintang

As the leader of the Green Gang, Du dominated Shanghai's opium and heroin trade in the 1930s, and secretly funded the political career of Chiang Kai-shek.[1] In contrast to his views on legality, Du was politically a staunch Confucian conservative. He had close ties with Chiang Kai-shek, who in turn had ties to both the Green Gang and other organised secret societies from his early years in Shanghai. Chiang forged political alliances throughout the 1920s, with some of the secret societies going as far as to offer their support in the 1927 Shanghai Purge. The resulting massacre ended the First United Front, and as a reward for Du's service, Chiang appointed him as the president of the National Board of Opium Suppression Bureau. The end result was that Du came to officially control the entirety of China's opium trade.

The Green Gang's support for the Nationalist Government included funding and equipment, even going as far as to purchase a German Junkers 87 emblazoned with the Board of Opium Suppression Bureau logo. In return, Du was given leeway to run labour unions and keep business flowing freely. In 1931, Du had the financial and political clout to open his own temple — one dedicated to his ancestors and family members — and hold a three-day-long party to honour its grand opening. It was one of Shanghai's largest celebrations, with hundreds of celebrities and political figures attending. Within months of its opening, however, the temple's private wings had been turned over to the manufacture of heroin, making it Shanghai's largest drug factory.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, Du offered to fight the Japanese by scuttling his fleet of ships at the mouth of the Yangtze River, but he eventually fled to Hong Kong and later to Chongqing. Green Gang operatives cooperating with Dai Li, Chiang's intelligence chief, continued to smuggle weapons and goods to the Kuomintang throughout the war, and Du himself was a board member of the Chinese Red Cross. Following Japan's surrender in 1945, Du returned to Shanghai, expecting a warm welcome but was shocked when he was not received like a hero. Many Shanghai residents felt that Du had abandoned the city, leaving its civilians to suffer under the atrocities of the Japanese occupation.

The relationship between Du and Chiang Kai-shek soured further after the war, when corruption and crime committed by top-ranking politicians and gangsters caused great problems within the Kuomintang. Chiang Kai-shek's son, Chiang Ching-kuo, launched an anti-corruption campaign in Shanghai in the late 1940s, with Du's relatives among the first to be arrested and thrown into jail. Although Du successfully managed their release by threatening to expose the embezzlement activities done by Chiang's relatives, the arrest and imprisonment of Du's sons effectively ended the partnership between Chiang and Du.

Exile in Hong Kong and death

Du escaped to Hong Kong after the Kuomintang retreated to Taiwan in 1949 following their defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Tales on Du's finances and power during this period vary largely — some argued that he lived in practical squalor while others said he had built up a sizable nest egg. As he gradually became blind and possibly senile, Du decided it was safe to move back to China in 1951. However, before he could return to China he died in Hong Kong, of illness apparently caused by his addiction to opium. Allegedly, his body was taken by one of his wives to Taiwan, and buried in Xizhi District, New Taipei, though some are sceptical that his tomb actually contains his body.[3] Following his internment the Taiwanese authorities constructed a statue of Du in Xizhi. The four-character inscription on the statue praises Du's "loyalty" and "personal integrity".[1]

Personal life

Du Yuesheng had five wives during his lifetime: Shen Yueying, Chen Yuying, Sun Peihao, Yao Yulan and Meng Xiaodong (divorced 1951). Du had eight sons and three daughters. His eight sons are Du Weiping, Du Weishan, Du Weixi, Du Weihan, Du Weiwei, Du Weining, Du Weixin and Du Weiwei. His three daughters are Du Meiru, Du Meixia and Du Meijuan.

According to Chan Wan Hoi's interview at Commercial Radio Hong Kong's "No.4 Mount Davis", Du's eldest daughter, Du Meiru, settled with her husband in Jordan in the 1960s and operated a restaurant.[4]

Names

Du's original name was Du Yuesheng (Chinese: 杜月生; pinyin: Dù Yuèshēng; Wade–Giles: Tu4 Yüeh4-sheng1). Later, on the advice of Zhang Binglin, Du changed his name to Du Yong (traditional Chinese: 杜鏞; simplified Chinese: 杜镛; pinyin: Dù Yōng; Wade–Giles: Tu4 Yung1), pseudonym Yuesheng (Chinese: 月笙; pinyin: Yuèshēng; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4-sheng1; same pronunciation as his original name but written differently in Chinese).[5]

In popular culture

For many years, media on Du and his exploits were officially banned in China on the grounds that they encourage criminality. Many Chinese-language biographies of Du were banned, and writers and sellers of these books were arrested. Only until recently did critical studies on Du become more open, but the official ban has never been entirely lifted by the Chinese government.

Some depictions of Du in popular culture include:

- The novel White Shanghai by Elvira Baryakina (Ripol Classic, 2010, ISBN 978-5-386-02069-9) mentions the story of Du's coming to power.

- Lord of the East China Sea (歲月風雲之上海皇帝), a 1993 Hong Kong film loosely based on Du's life. The lead character Lu Yunsheng (陸雲生), played by Ray Lui, is loosely based on Du. It has a sequel, Lord of the East China Sea II (上海皇帝之雄霸天下).

- The Founding of a Republic (建国大业), a 2009 Chinese historical film commissioned by the Chinese government. Du was portrayed by Feng Xiaogang as a minor character in the film.

- The Last Tycoon (大上海), a 2012 Hong Kong film loosely based on Du's life. The main character Cheng Daqi (成大器), portrayed by Chow Yun-fat and Huang Xiaoming at two different stages in his life, is loosely based on Du.

- In the 2015 Hong Kong TVB Drama Lord of Shanghai. The main character of the drama is based on Du Yuesheng which is named Kiu Ngo Tin. Kiu Ngo Tin is portrayed by Anthony Wong and the younger version of Kiu Ngo Tin is portrayed by Kenneth Ma.

- A cancelled video game Whore of the Orient was going to be set in 1936 Shanghai during Du's rule.

References

- Lintner, Bertil. Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency Since 1948. Silkworm Books. 1999. p.309

- Wakeman, Frederic, Jr. (1988). "Policing Modern Shanghai". China Quarterly (115): 417. (downloadable PDF)

- (in Chinese) 杜月笙--汐止文化網 Archived 2012-01-09 at the Wayback Machine

- chinanews. "杜月笙八旬长女约旦开餐馆 动脑不输年轻人(图)——中新网". www.chinanews.com. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- (in Chinese) 杜月笙的经典语录

- Zou Huilin (7 June 2001). "Du, the godfather of Shanghai". Shanghai Star. Archived from the original on 2007-08-21. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Du Yue-Sheng. |