Passerine

A passerine is any bird of the order Passeriformes, which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds or songbirds, passerines are distinguished from other orders of birds by the arrangement of their toes (three pointing forward and one back), which facilitates perching, amongst other features specific to their evolutionary history in Australaves.

| Passerine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top right: Palestine sunbird (Cinnyris osea), blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata), house sparrow (Passer domesticus), great tit (Parus major), hooded crow (Corvus cornix), southern masked weaver (Ploceus velatus) | |

| Song of a purple-crowned fairywren (Malurus coronatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Psittacopasserae |

| Order: | Passeriformes Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Suborders | |

|

and see text | |

| Diversity | |

| Roughly 140 families, 6,500 species | |

With more than 140 families and some 6,500 identified species,[1] Passeriformes is the largest order of birds and among the most diverse orders of terrestrial vertebrates. Passerines are divided into three suborders: Acanthisitti (New Zealand wrens), Tyranni (suboscines) and Passeri (oscines).[2][3] The passerines contain several groups of brood parasites such as the viduas, cuckoo-finches, and the cowbirds. Most passerines are omnivorous, while the shrikes are carnivorous.

The terms "passerine" and "Passeriformes" are derived from the scientific name of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus, and ultimately from the Latin term passer, which refers to sparrows and similar small birds.

Description

The order is divided into three suborders, Tyranni (suboscines), Passeri (oscines), and the basal Acanthisitti.[4] Oscines have the best control of their syrinx muscles among birds, producing a wide range of songs and other vocalizations (though some of them, such as the crows, do not sound musical to human beings); some such as the lyrebird are accomplished imitators. The acanthisittids or New Zealand wrens are tiny birds restricted to New Zealand, at least in modern times; they were long placed in Passeri.

Most passerines are smaller than typical members of other avian orders. The heaviest and altogether largest passerines are the thick-billed raven and the larger races of common raven, each exceeding 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) and 70 cm (28 in). The superb lyrebird and some birds-of-paradise, due to very long tails or tail coverts, are longer overall. The smallest passerine is the short-tailed pygmy tyrant, at 6.5 cm (2.6 in) and 4.2 g (0.15 oz).

Anatomy

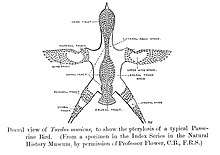

The foot of a passerine has three toes directed forward and one toe directed backward, called anisodactyl arrangement, and the hind toe (hallux) joins the leg at approximately the same level as the front toes. This arrangement enables passerine birds to easily perch upright on branches. The toes have no webbing or joining, but in some cotingas, the second and third toes are united at their basal third.

The leg of passerine birds contains an additional special adaptation for perching. A tendon in the rear of the leg running from the underside of the toes to the muscle behind the tibiotarsus will automatically be pulled and tighten when the leg bends, causing the foot to curl and become stiff when the bird lands on a branch. This enables passerines to sleep while perching without falling off.[5][6]

Most passerine birds have 12 tail feathers but the superb lyrebird has 16,[7] and several spinetails in the family Furnariidae have 10, 8, or even 6, as is the case of Des Murs's wiretail. Species adapted to tree trunk climbing such as woodcreeper and treecreepers have stiff tail feathers that are used as props during climbing. Extremely long tails used as sexual ornaments are shown by species in different families. A well-known example is the long-tailed widowbird.

Eggs and nests

The chicks of passerines are altricial: blind, featherless, and helpless when hatched from their eggs. Hence, the chicks require extensive parental care. Most passerines lay coloured eggs, in contrast with nonpasserines, most of whose eggs are white except in some ground-nesting groups such as Charadriiformes and nightjars, where camouflage is necessary, and in some parasitic cuckoos, which match the passerine host's egg. Vinous-throated parrotbill has two egg colours, white and blue. This can prevent the brood parasitic Common cuckoo.

Clutches vary considerably in size: some larger passerines of Australia such as lyrebirds and scrub-robins lay only a single egg, most smaller passerines in warmer climates lay between two and five, while in the higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, hole-nesting species like tits can lay up to a dozen and other species around five or six. The family Viduidae do not build their own nests, instead, they lay eggs in other birds' nests.

Origin and evolution

The evolutionary history of the passerine families and the relationships among them remained rather mysterious until the late 20th century. In many cases, passerine families were grouped together on the basis of morphological similarities that, it is now believed, are the result of convergent evolution, not a close genetic relationship. For example, the wrens of the Americas and Eurasia; those of Australia; and those of New Zealand look superficially similar and behave in similar ways, and yet belong to three far-flung branches of the passerine family tree; they are as unrelated as it is possible to be while remaining Passeriformes.[lower-alpha 1]

Much research remains to be done, but advances in molecular biology and improved paleobiogeographical data gradually are revealing a clearer picture of passerine origins and evolution that reconciles molecular affinities, the constraints of morphology and the specifics of the fossil record.[9][10] The first passerines are now thought to have evolved in the Southern Hemisphere in the late Paleocene or early Eocene, around 50 million years ago.[3][10]

The initial split was between the New Zealand wrens (Acanthisittidae) and all other passerines, and the second split involved the Tyranni (suboscines) and the Passeri (oscines or songbirds). The latter experienced a great radiation of forms out of the Australian continent. A major branch of the Passeri, parvorder Passerida, expanded deep into Eurasia and Africa, where a further explosive radiation of new lineages occurred.[10] This eventually led to three major Passerida lineages comprising about 4,000 species, which in addition to the Corvida and numerous minor lineages make up songbird diversity today. Extensive biogeographical mixing happens, with northern forms returning to the south, southern forms moving north, and so on.

Fossil record

Earliest passerines

Perching bird osteology, especially of the limb bones, is rather diagnostic.[11][12][13] However, the early fossil record is poor because the first Passeriformes were apparently on the small side of the present size range, and their delicate bones did not preserve well. Queensland Museum specimens F20688 (carpometacarpus) and F24685 (tibiotarsus) from Murgon, Queensland, are fossil bone fragments initially assigned to Passeriformes.[11] However, the material is too fragmentary and their affinities have been questioned.[14] Several more recent fossils from the Oligocene of Europe, such as Wieslochia, Jamna, and Resoviaornis, are more complete and definitely represent early passeriforms, although their exact position in the evolutionary tree is not known.

From the Bathans Formation at the Manuherikia River in Otago, New Zealand, MNZ S42815 (a distal right tarsometatarsus of a tui-sized bird) and several bones of at least one species of saddleback-sized bird have recently been described. These date from the Early to Middle Miocene (Awamoan to Lillburnian, 19–16 mya).[15]

Early European passerines

In Europe, perching birds are not too uncommon in the fossil record from the Oligocene onward, but most are too fragmentary for a more definite placement:

- Wieslochia (Early Oligocene of Frauenweiler, Germany)

- Resoviaornis (Early Oligocene of Wola Rafałowska, Poland)

- Jamna (Early Oligocene of Jamna Dolna, Poland)

- Winnicavis (Early Oligocene of Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland)

- Passeriformes gen. et sp. indet. (Early Oligocene of Luberon, France) – suboscine or basal[lower-alpha 2]

- Passeriformes gen. et spp. indet. (Late Oligocene of France) – several suboscine and oscine taxa[17][13]

- Passeriformes gen. et spp. indet. (Middle Miocene of France and Germany) – basal?[lower-alpha 3]

- Passeriformes gen. et spp. indet. (Sajóvölgyi Middle Miocene of Mátraszőlős, Hungary) – at least 2 taxa, possibly 3; at least one probably Oscines.[lower-alpha 4]

- Passeriformes gen. et sp. indet. (Middle Miocene of Felsőtárkány, Hungary) – oscine?[lower-alpha 5]

- Passeriformes gen. et sp. indet. (Late Miocene of Polgárdi, Hungary) – Sylvioidea (Sylviidae? Cettiidae?)[20]

That suboscines expanded much beyond their region of origin is proven by several fossil from Germany such as a broadbill (Eurylaimidae) humerus fragment from the Early Miocene (roughly 20 mya) of Wintershof, Germany, the Late Oligocene carpometacarpus from France listed above, and Wieslochia, among others.[12][10] Extant Passeri super-families were quite distinct by that time and are known since about 12–13 mya when modern genera were present in the corvoidean and basal songbirds. The modern diversity of Passerida genera is known mostly from the Late Miocene onwards and into the Pliocene (about 10–2 mya). Pleistocene and early Holocene lagerstätten (<1.8 mya) yield numerous extant species, and many yield almost nothing but extant species or their chronospecies and paleosubspecies.

American fossils

In the Americas, the fossil record is more scant before the Pleistocene, from which several still-existing suboscine families are documented. Apart from the indeterminable MACN-SC-1411 (Pinturas Early/Middle Miocene of Santa Cruz Province, Argentina),[lower-alpha 6] an extinct lineage of perching birds has been described from the Late Miocene of California, United States: the Palaeoscinidae with the single genus Palaeoscinis. "Palaeostruthus" eurius (Pliocene of Florida) probably belongs to an extant family, most likely passeroidean.

Systematics and taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationship of the suborders within the Passeriformes. The numbers are from the list published by the International Ornithologists' Union in January 2020.[1][23] |

The Passeriformes is currently divided into three suborders: Acanthisitti (New Zealand wrens), Tyranni (suboscines) and Passeri (oscines). The Passeri has been traditionally subdivided into two major groups recognized now as Corvida and Passerida respectively containing the large superfamilies Corvoidea and Meliphagoidea, as well as minor lineages, and the superfamilies Sylvioidea, Muscicapoidea, and Passeroidea but this arrangement has been found to be oversimplified. Since the mid-2000s, literally, dozens of studies have investigated the phylogeny of the Passeriformes and found that many families from Australasia traditionally included in the Corvoidea actually represent more basal lineages within oscines. Likewise, the traditional three-superfamily arrangement within the Passeri has turned out to be far more complex and will require changes in classification.

Major "wastebin" families such as the Old World warblers and Old World babblers have turned out to be paraphyletic and are being rearranged. Several taxa turned out to represent highly distinct lineages, so new families had to be established, some of them – like the stitchbird of New Zealand and the Eurasian bearded reedling – monotypic with only one living species.[24] In the Passeri alone, a number of minor lineages will eventually be recognized as distinct superfamilies. For example, the kinglets constitute a single genus with less than 10 species today but seem to have been among the first perching bird lineages to diverge as the group spread across Eurasia. No particularly close relatives of them have been found among comprehensive studies of the living Passeri, though they might be fairly close to some little-studied tropical Asian groups. Nuthatches, wrens, and their closest relatives as currently grouped in a distinct super-family Certhioidea.

Taxonomic list of Passeriformes families

This list is in taxonomic order, placing related families next to one another. The families listed are those recognised by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOC).[1] The order and the division into infraorders, parvorders and superfamilies follows the phylogenetic analysis published by Carl Oliveros and colleagues in 2019.[23][lower-alpha 7] The relationships between the families in the suborder Tyranni (suboscines) were all well determined but some of the nodes in Passeri (oscines) were unclear owing to the rapid splitting of the lineages.[23]

Suborder Acanthisitti

- Acanthisittidae: New Zealand wrens

_-San_Diego_Zoo-8.jpg)

Suborder Tyranni (suboscines)

- Infraorder Eurylaimides: Old World suboscines

- Philepittidae: asities

- Eurylaimidae: typical broadbills

- Calyptomenidae: African and green broadbills

- Sapayoidae: broad-billed sapayoa

- Pittidae: pittas

- Infraorder Tyrannides: New World suboscines

- Parvorder Furariida

- Melanopareiidae: crescentchests

- Conopophagidae: gnateaters and gnatpittas

- Thamnophilidae: antbirds

- Grallariidae: antpittas

- Rhinocryptidae: typical tapaculos

- Formicariidae: antthrushes

- Furnariidae: ovenbirds and woodcreepers

- Parvorder Tyrannida

- Pipridae: manakins

- Cotingidae: cotingas

- Tityridae: tityras and allies

- Tyrannidae: tyrant flycatchers

Suborder Passeri (oscines)

- Atrichornithidae: scrub-birds

- Menuridae: lyrebirds

- Climacteridae: Australian treecreepers

- Ptilonorhynchidae: bowerbirds

- Maluridae: fairywrens, emu-wrens and grasswrens

- Dasyornithidae: bristlebirds

- Pardalotidae: pardalotes

- Acanthizidae: scrubwrens, thornbills, and gerygones

- Meliphagidae: honeyeaters

- Pomatostomidae: pseudo-babblers

- Orthonychidae: logrunners

- Infraorder Corvides

- Cinclosomatidae: jewel-babblers, quail-thrushes

- Campephagidae: cuckooshrikes and trillers

- Mohouidae: whiteheads

- Neosittidae: sittellas

- Superfamily Orioloidea[lower-alpha 8]

- Psophodidae: whipbirds

- Eulacestomidae: wattled ploughbills

- Falcunculidae: shriketit

- Oreoicidae: Australo-Papuan bellbirds

- Paramythiidae: painted berrypeckers

- Vireonidae: vireos

- Pachycephalidae: whistlers

- Oriolidae: Old World orioles and figbirds

- Superfamily Malaconotoidea[lower-alpha 9]

- Machaerirhynchidae: boatbills

- Artamidae: woodswallows, butcherbirds, currawongs, and Australian magpie

- Rhagologidae: mottled whistler

- Malaconotidae: puffback shrikes, bush shrikes, tchagras, and boubous

- Pityriaseidae: bristlehead

- Aegithinidae: ioras

- Platysteiridae: wattle-eyes and batises

- Vangidae: vangas

- Superfamily Corvoidea[lower-alpha 10]

- Rhipiduridae: fantails

- Dicruridae: drongos

- Monarchidae: monarch flycatchers

- Ifritidae: blue-capped ifrit

- Paradisaeidae: birds-of-paradise

- Corcoracidae: white-winged chough and apostlebird

- Melampittidae: melampittas

- Laniidae: shrikes

- Corvidae: crows, ravens, and jays

- Infraorder Passerides

- Cnemophilidae: satinbirds

- Melanocharitidae: berrypeckers and longbills

- Callaeidae: New Zealand wattlebirds

- Notiomystidae: stitchbird

- Petroicidae: Australian robins

- Eupetidae: rail-babbler

- Picathartidae: rockfowl

- Chaetopidae: rock-jumpers

- Parvorder Sylviida[lower-alpha 11]

- Hyliotidae: hyliotas

- Stenostiridae: fairy flycatchers

- Paridae: tits, chickadees and titmice

- Remizidae: penduline tits

- Panuridae: bearded reedling

- Alaudidae: larks

- Nicatoridae: nicators

- Macrosphenidae: crombecs and African warblers

- Cisticolidae: cisticolas and allies

- Superfamily Locustelloidea

- Acrocephalidae: reed warblers, Grauer’s warbler and allies

- Locustellidae: grassbirds and allies

- Donacobiidae: black-capped donacobius

- Bernieridae: Malagasy warblers

- —

- Pnoepygidae: wren-babblers

- Hirundinidae: swallows and martins

- Superfamily Sylvioidea

- Pycnonotidae: bulbuls

- Sylviidae: sylviid babblers

- Paradoxornithidae: parrotbills and myzornis

- Zosteropidae: white-eyes

- Timaliidae: tree babblers

- Leiothrichidae: laughingthrushes and allies

- Alcippeidae: Alcippe fulvettas

- Pellorneidae: ground babblers

- Superfamily Aegithaloidea

- Phylloscopidae: leaf-warblers and allies

- Hyliidae: hylias

- Aegithalidae: long-tailed tits or bushtits

- Scotocercidae: streaked scrub warbler

- Cettiidae: Cettia bush warblers and allies

- Erythrocercidae: yellow flycatchers

- Parvorder Muscicapida

- Superfamily Bombycilloidea

- Dulidae: palmchat

- Bombycillidae: waxwings

- Ptiliogonatidae: silky flycatchers

- Hylocitreidae: hylocitrea

- Hypocoliidae: hypocolius

- Mohoidae: oos

%2C_M._A._Pe%C3%B1a.jpg)

- Superfamily Muscicapoidea

- Elachuridae: spotted elachura

- Cinclidae: dippers

- Muscicapidae: Old World flycatchers and chats

- Turdidae: thrushes and allies

- Buphagidae: oxpeckers

- Sturnidae: starlings and rhabdornis

- Mimidae: mockingbirds and thrashers

- —

- Regulidae: goldcrests and kinglets

- Superfamily Certhioidea

- Tichodromidae: wallcreeper

- Sittidae: nuthatches

- Certhiidae: treecreepers

- Polioptilidae: gnatcatchers

- Troglodytidae: wrens

- Parvorder Passerida

- Promeropidae: sugarbirds

- Modulatricidae: dapple-throat and allies

- Nectariniidae: sunbirds

- Dicaeidae: flowerpeckers

- Chloropseidae: leafbirds

- Irenidae: fairy-bluebirds

- Peucedramidae: olive warbler

- Urocynchramidae: Przewalski's finch

- Ploceidae: weavers

- Viduidae: indigobirds and whydahs

- Estrildidae: waxbills, munias and allies

- Prunellidae: accentors

- Passeridae: Old World sparrows and snowfinches

- Motacillidae: wagtails and pipits

- Fringillidae: finches and euphonias

- Superfamily Emberizoidea (previously known as the nine-primaried oscines[26])[lower-alpha 12]

- Rhodinocichlidae: rosy thrush-tanager

- Calcariidae: longspurs and snow buntings

- Emberizidae: buntings

- Cardinalidae: cardinals

- Mitrospingidae: mitrospingid tanagers

- Thraupidae: tanagers and allies

- Passerellidae: New World sparrows, bush tanagers

- Parulidae: New World warblers

- Icteriidae: yellow-breasted chat

- Icteridae: grackles, New World blackbirds, and New World orioles

- Calyptophilidae: chat-tanagers

- Zeledoniidae: wrenthrush

- Teretistridae: Cuban warblers[lower-alpha 13]

- Nesospingidae: Puerto Rican tanager

- Spindalidae: spindalises

- Phaenicophilidae: Hispaniolan tanagers

Phylogeny

Living Passeriformes based on the "Taxonomy in Flux family phylogenetic tree" by John Boyd.[28]

| Passeriformes classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Notes

- The name wren has been applied to other, unrelated birds in Australia and New Zealand. The 27 Australasian "wren" species in the family Maluridae are unrelated, as are the New Zealand wrens in the family Acanthisittidae; the antwrens in the family Thamnophilidae; and the wren-babblers of the families Timaliidae, Pellorneidae, and Pnoepygidae. For the monophyly of the "true wrens", Troglodytidae, see Barker 2004[8]

- Specimen SMF Av 504. A flattened right hand of a passerine perhaps 10 cm long overall. If suboscine, perhaps closer to Cotingidae than to Eurylaimides.[16][13]

- Specimens SMF Av 487–496; SMNS 86822, 86825-86826; MNHN SA 1259–1263: tibiotarsus remains of small, possibly basal Passeriformes.[12]

- A partial coracoid of a probable Muscicapoidea, possibly Turdidae; distal tibiotarsus and tarsometatarsus of a smallish to mid-sized passerine that may be the same as the preceding; proximal ulna and tarsometatarsus of a Paridae-sized passerine.[18][19]

- A humerus diaphysis piece of a swallow-sized passerine.[20]

- Distal right humerus, possibly suboscine.[21][22]

- Oliveros et al (2019) use the list of families published by Dickinson and Christidis in 2014.[23][25] Oliveros et al include 10 families that are not included on the IOC list. These are not shown here. By contrast, the IOC list includes nine families that are not present in Dickinson and Christidis. In eight of these cases, the position of the additional family in the taxonomic order can be determined from the species included by Oliveros and colleagues in their analysis. No species in the family Teretistridae was sampled by Oliveros et al so its position is uncertain.[1][23]

- The order of the families within the superfamily Orioloidea is uncertain.[23]

- The order of the families within the superfamily Malaconotoidea is uncertain.[23]

- The order of the families within the superfamily Corvoidea is uncertain.[23]

- The taxonomic sequence of the superfamilies Locustelloidea, Sylvioidea and Aegithaloidea is uncertain, although the order of the families within each of the superfamilies is well determined.[23]

- The order of some of the families within the superfamily Emberizoidea is uncertain.[23]

- The family Teretistridae (Cuban warblers) is tentatively placed here. The family was not included in the analysis published by Oliveros et al (2019).[23] Dickinson and Christidis (2014) considered the genus Teretistris Incertae sedis.[27] Barker et al (2013) found that Teretistridae is closely related to Zeledoniidae.[26]

References

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Family Index". IOC World Bird List Version 10.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Barker, F. Keith; Barrowclough, George F.; Groth, Jeff G. (2002). "A phylogenetic hypothesis for passerine birds: Taxonomic and biogeographic implications of an analysis of nuclear DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 269 (1488): 295–308. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1883. PMC 1690884. PMID 11839199.

- Ericson, P.G.; Christidis, L.; Cooper, A.; Irestedt, M.; Jackson, J.; Johansson, U.S.; Norman, J.A. (7 February 2002). "A Gondwanan origin of passerine birds supported by DNA sequences of the endemic New Zealand wrens". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 269 (1488): 235–241. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1877. PMC 1690883. PMID 11839192.

- Chatterjee, Sankar (2015). The Rise of Birds: 225 Million Years of Evolution. JHU Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 9781421415901.

- Stefoff, Rebecca (2008), The Bird Class, Marshall Cavendish Benchmark

- Brooke, Michael and Birkhead, Tim (1991) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Ornithology, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0521362059.

- Jones, D. (2008) "Flight of fancy". Australian Geographic, (89), 18–19.

- Barker, F.K. (2004). "Monophyly and relationships of wrens (Aves: Troglodytidae): a congruence analysis of heterogeneous mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 31 (2): 486–504. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.08.005. PMID 15062790.

- Dyke, Gareth J.; Van Tuinen, Marcel (June 2004). "The evolutionary radiation of modern birds (Neornithes): Reconciling molecules, morphology and the fossil record". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 141 (2): 153–177. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00118.x.

- Claramunt, S.; Cracraft, J. (2015). "A new time tree reveals Earth history's imprint on the evolution of modern birds". Science Advances. 1 (11): e1501005. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501005. PMC 4730849. PMID 26824065.

- Boles, Walter E. (1997). "Fossil songbirds (Passeriformes) from the Early Eocene of Australia". Emu. 97 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1071/MU97004.

- Manegold, Albrecht; Mayr, Gerald & Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile (2004). "Miocene Songbirds and the Composition of the European Passeriform Avifauna". Auk. 121 (4): 1155–1160. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[1155:MSATCO]2.0.CO;2.

- Mayr, Gerald & Manegold, Albrecht (2006). "A Small Suboscine-like Passeriform Bird from the Early Oligocene of France". Condor. 108 (3): 717–720. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2006)108[717:ASSPBF]2.0.CO;2.

- Mayr, G (2013). "The age of the crown group of passerine birds and its evolutionary significance–molecular calibrations versus the fossil record". Systematics and Biodiversity. 11 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1080/14772000.2013.765521.

- Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Jones, C.; McNamara, J.A.; Douglas, B.J. (2007). "Miocene waterfowl and other birds from central Otago, New Zealand". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001957. hdl:2440/43360.

- Roux, T. (2002). "Deux fossiles d'oiseaux de l'Oligocène inférieur du Luberon" [Two bird fossils from the Lower Oligocene of Luberon] (PDF). Courrier Scientifique du Parc Naturel Régional du Luberon. 6: 38–57.

- Hugueney, Marguerite; Berthet, Didier; Bodergat, Anne-Marie; Escuillié, François; Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile & Wattinne, Aurélia (2003). "La limite Oligocène-Miocène en Limagne: changements fauniques chez les mammifères, oiseaux et ostracodes des différents niveaux de Billy-Créchy (Allier, France)" [The Oligocene-Miocene boundary in Limagne: faunal changes in the mammals, birds and ostracods from the different levels of Billy-Créchy (Allier, France)]. Geobios. 36 (6): 719–731. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2003.01.002.

- Gál, Erika; Hír, János; Kessler, Eugén & Kókay, József (1998–99). "Középsõ-miocén õsmaradványok, a Mátraszõlõs, Rákóczi-kápolna alatti útbevágásból. I. A Mátraszõlõs 1. lelõhely" [Middle Miocene fossils from the sections at the Rákóczi chapel at Mátraszőlős. Locality Mátraszõlõs I.]. Folia Historico Naturalia Musei Matraensis. 23: 33–78.

- Gál, Erika; Hír, János; Kessler, Eugén, Kókay, József & Márton, Venczel (2000). "Középsõ-miocén õsmaradványok a Mátraszõlõs, Rákóczi-kápolna alatti útbevágásból II. A Mátraszõlõs 2. lelõhely" [Middle Miocene fossils from the section of the road at the Rákóczi Chapel, Mátraszõlõs. II. Locality Mátraszõlõs 2]. Folia Historico Naturalia Musei Matraensis. 24: 39–75.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hír, János; Kókay, József; Venczel, Márton; Gál, Erika & GKessler, Eugén (2001). "Elõzetes beszámoló a felsõtárkányi "Güdör-kert" n. õslénytani lelõhelykomplex újravizsgálatáról" [A preliminary report on the revised investigation of the paleontological locality-complex "Güdör-kert" at Felsõtárkány, Northern Hungary] (PDF). Folia Historico Naturalia Musei Matraensis. 25: 41–64.

- Noriega, Jorge I. & Chiappe, Luis M. (1991). "El más antiguo Passeriformes de America del Sur. Presentation at VIII Journadas Argentinas de Paleontologia de Vertebrados" [The most ancient passerine from South America]. Ameghiniana. 28 (3–4): 410.

- Noriega, Jorge I. & Chiappe, Luis M. (1993). "An Early Miocene Passeriform from Argentina" (PDF). Auk. 110 (4): 936–938. doi:10.2307/4088653. JSTOR 4088653.

- Oliveros, C.H.; et al. (2019). "Earth history and the passerine superradiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (16): 7916–7925. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813206116. PMC 6475423. PMID 30936315.

- The former does not even have recognized subspecies, while the latter is one of the most singular birds alive today. Good photos of a bearded reedling are for example here Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine and here Archived 31 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Dickinson, E.C.; Christidis, L., eds. (2014). The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines (4th ed.). Eastbourne, UK: Aves Press. ISBN 978-0-9568611-2-2.

- Barker, F.K.; Burns, K.J.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2013). "Going to extremes: contrasting rates of diversification in a recent radiation of New World passerine birds". Systematic Biology. 62 (2): 298–320. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys094. PMID 23229025.

- Dickinson, E.C.; Christidis, L., eds. (2014). The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 2: Passerines (4th ed.). Eastbourne, UK: Aves Press. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-9568611-2-2.

- John Boyd. "Taxonomy in Flux family phylogenetic tree" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Alström, Per; Ericson, Per G.P.; Olsson, Urban & Sundberg, Per (2006). "Phylogeny and classification of the avian super-family Sylvioidea". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (2): 381–397. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.015. PMID 16054402.

- Barker, F. Keith; Barrowclough, George F. & Groth, Jeff G. (2002). "A phylogenetic hypothesis for passerine birds: taxonomic and biogeographic implications of an analysis of nuclear DNA sequence data" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 269 (1488): 295–308. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1883. PMC 1690884. PMID 11839199.

- Barker, F. Keith; Cibois, Alice; Schikler, Peter A.; Feinstein, Julie & Cracraft, Joel (2004). "Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation". PNAS. 101 (30): 11040–11045. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111040B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101. PMC 503738. PMID 15263073. Supporting information

- Beresford, P.; Barker, F.K.; Ryan, P.G. & Crowe, T.M. (2005). "African endemics span the tree of songbirds (Passeri): molecular systematics of several evolutionary 'enigmas'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 272 (1565): 849–858. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2997. PMC 1599865. PMID 15888418.

- Cibois, Alice; Slikas, Beth; Schulenberg, Thomas S. & Pasquet, Eric (2001). "An endemic radiation of Malagasy songbirds is revealed by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Evolution. 55 (6): 1198–1206. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[1198:AEROMS]2.0.CO;2. PMID 11475055.

- Ericson, Per G.P. & Johansson, Ulf S. (2003). "Phylogeny of Passerida (Aves: Passeriformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial sequence data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 29 (1): 126–138. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00067-8. PMID 12967614.

- Johansson, Ulf S. & Ericson, Per G.P. (2003). "Molecular support for a sister group relationship between Pici and Galbulae (Piciformes sensu Wetmore 1960)" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 34 (2): 185–197. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048X.2003.03103.x.

- Jønsson, Knud A. & Fjeldså, Jon (2006). "A phylogenetic supertree of oscine passerine birds (Aves: Passeri)". Zoologica Scripta. 35 (2): 149–186. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2006.00221.x.

- Lovette, Irby J. & Bermingham, Eldredge (2000). "c-mos Variation in Songbirds: Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetic Implications, and Comparisons with Mitochondrial Differentiation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 17 (10): 1569–1577. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026255. PMID 11018162.

- Mayr, Gerald (2016). Avian evolution: the fossil record of birds and its paleobiological significance. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-02076-9.

- Raikow, Robert J. (1982). "Monophyly of the Passeriformes: test of a phylogenetic hypothesis" (PDF). The Auk. 99 (3): 431–445. doi:10.1093/auk/99.3.431. Lay summary.

External links

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Passeriformes |