Superb lyrebird

The superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) is an Australian songbird, one of two species from the family Menuridae. It is one of the world's largest songbirds, and is renowned for its elaborate tail and courtship displays, and its excellent mimicry. The species is endemic to Australia and is found in forest in the southeast of the country. According to David Attenborough, the superb lyrebird displays the most sophisticated voice skills within the animal kingdom—"the most elaborate, the most complex, and the most beautiful".[2]

| Superb lyrebird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Menuridae |

| Genus: | Menura |

| Species: | M. novaehollandiae |

| Binomial name | |

| Menura novaehollandiae Latham, 1801 | |

Taxonomy

The superb lyrebird was first illustrated and described scientifically as Menura superba by Major-General Thomas Davies on 4 November 1800 to the Linnean Society of London.[3][4]

Superb lyrebirds are passerine birds within the family Menuridae, being one of the two species of lyrebirds forming the genus Menura, with the other being the much rarer Albert's lyrebird.[5] The superb lyrebird can be distinguished from Albert's lyrebird by its slightly larger size, less reddish colour and more ornate tail feathers.[6]

The generic name Menura derives from Ancient Greek mēnē 'moon' and oura 'tail', referring to the numerous transparent lunules in the inner webs of the outer tail-feathers (as described by John Latham in 1801).[7] The specific epithet derives from Modern Latin Nova Hollandia 'New Holland', the name given by early Dutch explorers to Western Australia.[7]

Lyrebirds are ancient Australian animals. The Australian Museum contains fossils of lyrebirds dating back to about 15 million years ago.[8] The prehistoric Menura tyawanoides has been described from early Miocene fossils found at the famous Riversleigh site.

Distribution and habitat

The superb lyrebird is endemic to Australia and is found in the forest of southeastern Australia, ranging from southern Victoria to southeastern Queensland.[9]

The bird was introduced to southern Tasmania in 1934–54, amid ill-founded fears the species was becoming threatened with extinction in its mainland populations.[10][11] The Tasmania population is thriving and even growing.[10][11] Across the rest of its large range, the lyrebird is common, and is evaluated as being of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1]

This range of the superb lyrebird includes a variety of biomes, including subtropical and temperate rainforest, and wet and dry sclerophyll forest.[9] The preferred habitat of the bird is in wet forest and rainforest, where there is an open ground layer of moist leaf litter shaded by vegetation.[12] In favourable seasons, the lyrebird range is often extended into drier areas further from water sources.[13][12]

Description

The superb lyrebird is a large, pheasant-sized terrestrial passerine, ranging in length from 860 mm (34 in) for the female to 1 m (39 in) for the male.[6] Females weigh around 0.9 kg (2.0 lb), and males weigh around 1.1 kg (2.4 lb).[5] The plumage colour is mainly dark brown on the upper body, with greyish-brown underparts and red-tinged flight feathers.[5] The wings are short and round, and are only capable of weak flight, being mainly used for balance or for gliding from trees to the ground.[6] The legs are powerful, capable of running quickly, and the feet are strong enough to move branches up to 10 cm in diameter.[6]

Lyrebirds are renowned for their ornate tails. Adult males have tails up to 700 mm (28 in) long, consisting of sixteen feathers. The outer two feathers, the lyrates, are broad S-shaped feathers, originally named for their resemblance to the shape of a lyre, and have brown and buff coloured patterning. Between the lyrates are twelve filamentaries, feathers of flexible silvery barbs. In the centre of the tail are two silvery median feathers. The tail of the female is less ornate, with shorter lyrates and plain, broad feathers in place of the filamentaries.[6] In both sexes, juveniles have no ornamental tail feathers. The tail plumage develops into that of the mature bird through a series of annual moults, with feathers undergoing change in structure and patterning. The male superb lyrebird reaches maturity in 7–9 years, and the female in 6–7 years.[14]

Behaviour and ecology

Superb lyrebirds are ground-dwelling birds that typically live solitary lives. Adults usually live singly in territories, but young birds without territories may associate in small groups which can be single or mixed-sex.[15] Lyrebirds are not strong fliers and are not highly mobile, often remaining within the same area for their entire lifespans.[16] Superb lyrebird territories are generally small, and there are known behavioural differences between different populations.[17]

Diet and foraging

The diet of the superb lyrebird consists primarily of invertebrates such as earthworms and insects found on the forest floor.[6] There is also evidence that the birds are mycophagists, meaning that they eat fungi.[17]

Superb lyrebirds forage by scratching vigorously in the upper soil layers, disturbing the topsoil and leaf litter.[17] The birds are most likely to forage in damp rainforest vegetation relative to drier areas, and in areas where the bottom vegetation strata is open and low in complexity, allowing good access to food sources in the leaf litter.[12]

Mating and breeding

Superb lyrebirds exhibit polygyny, with a single male mating with several females.[18] A male's territory can overlap with up to six female territories. Within his territory, the male will construct several circular mounds of bare dirt on the forest floor, for the purpose of conducting courtship displays. These mounds are defended vigorously from other males.[6]

There is strong sexual selection in lyrebirds, with females visiting the territories of several different males and choosing the most desirable males with which to copulate.[19][18] When a male encounters a female lyrebird, he performs an elaborate courtship display on the nearest mound. This display incorporates both song and dance elements. The male fans out his tail horizontally to cover his entire body and head. The tail feathers are vibrated, and the lyrebird beats his wings against his body and struts around the mound.[6] He also sings loudly, incorporating his own vocalisations with mimicry of other bird calls.[6] A study has found evidence that the lyrebirds’ ‘dance choreography’ is highly coordinated to different types of song repertoire. Coordination of movement with acoustic signals is a trait previously thought to be unique to humans, and indicates high cognitive ability.[20]

Females are the sole providers of parental care.[19] They build large domed nests out of sticks on raised earth platforms. Nests are most likely to be located in wetter areas with deep leaf litter and high understory vegetation complexity, reflecting the requirements of food availability and protection from predators.[12]

The female breeds once per year in winter, usually laying a single egg.[21] Eggs are laid in a deep bed of lyrebird feathers within the nest, and are then incubated by the female for up to 7 weeks.[6] Post-fledging parental care lasts several months, with the female exerting significant energy in feeding and brooding the nestling.[19]

Vocalisation and mimicry

The superb lyrebird is renowned for its mimicry, with an estimated 70-80% of the male's vocalisations consisting of imitations of other model bird species.[22] Females also sing and are capable of mimicry, although not to the extent of the males.[23] Mimetic items can be interspersed with lyrebird-specific songs, territorial calls, and alarm calls.[9] The songs adhere to recognisable structures, with different elements repeated in certain patterns.[9]

The mimicry of the superb lyrebird is highly accurate, with even the model animal at times unable to distinguish between model song and mimicked song. For example, one study found that strike-thrushes did not respond any differently to hearing their own songs than to hearing imitations by lyrebirds.[18]

Generally, juveniles initially learn mimetic items through transmission by older lyrebirds, rather than from the model species themselves.[24] This is reflected in the vocalisations of lyrebirds in the Sherbrooke Forest in Victoria, which were observed to frequently mimic the song of pilotbirds, a species that had not been recorded in the area for over 10 years.[24] During the winter when the nestlings hatch, adults more frequently mimic model species that are less active during this time, again suggesting that mimetic items are initially learnt from other lyrebirds.[9]

The quality of mimetic song increases with age, with adult superb lyrebirds having both greater accuracy and a more diverse repertoire of mimetic songs when compared to subadult birds.[24][18] Subadult lyrebirds produce recognisable imitations, which fall short of adult versions in terms of frequency range, consistency and acoustic purity, for example in imitations of the complex whipbird call.[24]

Like many passerine species, there are significant differences in lyrebird song in different populations over its geographic range.[16] These include differences in repertoire and vocalisation characteristics, and may be due to differences in local bird species assemblages, which provide different options for model selection.[9] It could also be due to differences in the acoustic environment mediated by vegetation structure, with lyrebirds more likely to mimic fragments of bird songs that are most acoustically prominent.[9]

Mimicry as a sexually selected trait

The mimicry of male superb lyrebirds is a well-known example of a sexually selected trait. Females prefer males that produce more accurate mimicry and that have a greater diversity of mimetic songs in their repertoire.[24] Although to the human ear the differences between songs are indistinguishable, there are differences in the mimetic song quality between individual lyrebirds due to signal degradation, reverberation and attenuation, as well as the frequency and volume attained.[24] There is evidence that there are costs associated with the development of mimetic song, and while these costs are currently unknown, they indicate that that quality of a lyrebird's mimetic song is an honest signal that can be used by females in mate selection.[24]

Mimicry in females

Historically, there has been far more research on the mimetic abilities of male lyrebirds. This is primarily due to the assumption that the evolution of song in passerines resulted primarily from the selection on males in attracting mates or deterring rivals.[23] However, a study found that females also produced mimetic vocalisations while foraging and during nest defence, suggesting that mimicry has a function in deterring predators and conspecific rivals.[23]

Mimicry of anthropogenic sounds

In David Attenborough's Life of Birds (ep. 6), the superb lyrebird is described as able to imitate twenty bird species' calls, and a male is shown mimicking a car alarm, chainsaw, and various camera shutters. However, two of the three lyrebirds featured were captive birds.[25] One of the three was observed imitating a laughing kookaburra with such close similarity that a nearby kookaburra began responding to the lyrebird and calling back.[26]

A recording of a superb lyrebird mimicking sounds of an electronic shooting game, workmen, and chainsaws was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia registry in 2013.[27] The vocalizations of some superb lyrebirds in the New England area of New South Wales are said to possess a flute-like timbre.[28]

Ecosystem engineers

The foraging behaviour of the superb lyrebird has a major effect on the structure of the forest floor. A lyrebird can move and bury up to 200 tonnes per hectare of leaf litter and soil every year, disturbing the soil to a greater extent than virtually any other animal.[13] This soil disturbance hastens the decomposition of the leaf litter, and increases the rate of nutrient cycling in the ecosystem.[13] The lyrebirds’ clearing of bare patches also reduces the amount of fuel available for forest fires, which in turn reduces the extent and intensity of wildfires.[29]

Threats and predators

Superb lyrebirds are vulnerable to native predatory birds such as the collared sparrowhawk, gray goshawk, and currawongs.[23] Nests are particularly vulnerable to predation, but adults are also vulnerable due to their loud calls.[9][23] It has been observed that males suffer higher degrees of mortality, suggesting that their courtship displays render them highly vulnerable.[30] Methods utilised by superb lyrebirds to reduce predation risk include selection of protected areas for nest sites, mimicking calls of other predatory birds, and adopting solitary and timid behaviours.[9][23][12]

As the superb lyrebird is a poor flyer, when alarmed it will tend to run away, sometimes incorporating short gliding flights to lower perches or downhill.[5]

Human factors also pose threats to superb lyrebirds. Because they are ground-dwelling, superb lyrebirds are particularly threatened by vehicle collisions.[12] The presence of roads and infrastructure also pose edge effects, for example disturbance from domestic animals and predation by introduced species such as the red fox, which is often associated with urban areas.[12]

In culture

An instantly recognisable bird, the superb lyrebird has been featured as an emblem many times. Notable examples of this include a male superb lyrebird being featured on the reverse side of the Australian 10-cent coin,[31] and as the emblem of the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service.[32]

Museum specimens

John Gould's historic painting of a male and female pair of superb lyrebirds has the tail feathers of the male incorrectly displayed, with the lyrates in the centre of the plume surrounded by the filamentaries. This happened when a superb lyrebird specimen was prepared for display at the British Museum by a taxidermist who had never seen a live lyrebird, and Gould later painted his artwork from this incorrect presentation.

A specimen of a male superb lyrebird, at the American Museum of Natural History, also has the tail feathers displayed incorrectly.

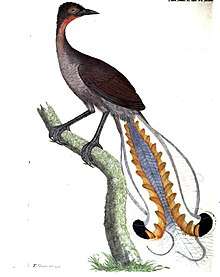

Menura superba – superb lyrebird (1800) by Thomas Davies

Menura superba – superb lyrebird (1800) by Thomas Davies John Gould's early 1800s painting of museum specimens of a male superb lyrebird (with tail feathers incorrectly displayed) and a female superb lyrebird

John Gould's early 1800s painting of museum specimens of a male superb lyrebird (with tail feathers incorrectly displayed) and a female superb lyrebird A male superb lyrebird museum specimen

A male superb lyrebird museum specimen

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Menura novaehollandiae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- BBC Earth (18 May 2009), Attenborough: the amazing Lyre Bird sings like a chainsaw! Now in high quality | BBC Earth, retrieved 21 May 2018

- Davies, Thomas (4 November 1800). . Transactions of the Linnean Society. 6. London (published 1802). pp. 207–10.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Menkhorst, P.; Rodgers, D.; Clarke, R.; Davies, J.; Marsack, P.; Franklin, K. (2017). The Australian Bird Guide. Clayton: CSIRO Publishing.

- Reilly, P.N. (1988). The Lyrebird: a natural history. New South Wales University Press.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). "Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird-names". Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Boles, Walter (2011). "Lyrebird: Overview". Pulse of the Planet. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- Robinson, F.N.; Curtis, S. (1996). "The vocal displays of the lyrebirds (Menuridae)". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 96 (4): 258–275. doi:10.1071/MU9960258.

- Smith, L.H. (1997). "Building a viable lyrebird population". Australian Bird Watcher. 17: 71–80.

- Pizzey, G.; Knight, F. (2003). The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia (2 ed.). HarperCollins Publishers.

- Maisey, A.C.; Nimmo, D.G.; Bennett, A.F. (2019). "Habitat selection by the superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae), an iconic ecosystem engineer in forests of south-eastern Australia". Austral Ecology. 44 (3): 503–513. doi:10.1111/aec.12684.

- Ashton, D.H.; Bassett, O.D. (1997). "The effects of foraging by the superb lyrebird (Menura novae-hollandiae) in Eucalyptus regnans forests at Beenak, Victoria". Australian Journal of Ecology. 22 (4): 383–394. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1997.tb00688.x.

- Smith, L.H. (2004). "Structural changes in the lyrate feathers in the development of the tail plumage of the superb lyrebird, Menura novaehollandiae". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 104: 59–73. doi:10.1071/MU01020.

- Lill, A.; Boesman, P.F.D. (2020). "Superb Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae), version 1.0". In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Powys, V. (1995). "Regional variation in the territorial songs of superb lyrebirds in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 95 (4): 280–289. doi:10.1071/MU9950280.

- Elliott, T.F.; Vernes, K. (2019). "Superb lyrebird Menura novaehollandiae mycophagy, truffles and soil disturbance". International Journal of Avian Science. 161: 198–204.

- Dalziell, A.H.; Magrath, R.D. (2012). "Fooling the experts: accurate vocal mimicry in the song of the superb lyrebird, Menura novaehollandiae". Animal Behaviour. 83 (6): 1401–1410. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.03.009.

- Lill, A. (1979). "An assessment of male parental investment and pair bonding in the polygamous superb lyrebird". The Auk. 96: 489–498.

- Dalziell, A.H.; Peters, R.A.; Cockburn, A.; Dorland, A.D.; Maisey, A.C.; Magrath, R.D. (2013). "Dance choreography is coordinated with song repertoire in a complex avian display". Current Biology. 23 (12): 1132–1135. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.018. PMID 23746637.

- Reilly, P.N. (1970). "Nesting of the superb lyrebird in Sherbrooke Forest, Victoria". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 70 (2): 73–78. doi:10.1071/MU970073.

- Dalziell, A.H.; Welbergen, J.A.; Igic, B.; Magrath, R.D. (2015). "Avian vocal mimicry: a unified conceptual framework". Biological Reviews. 90 (2): 643–668. doi:10.1111/brv.12129. PMID 25079896.

- Dalziell, A.H.; Welbergen, J.A. (2016). "Elaborate mimetic vocal displays by female superb lyrebirds". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00034.

- Zann, R.; Dunstan, E. (2008). "Mimetic song in superb lyrebirds: species mimicked and mimetic accuracy in different populations and age classes". Animal Behaviour. 76 (3): 1043–1054. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.05.021.

- Taylor, Hollis (3 February 2014). "Lyrebirds mimicking chainsaws: fact or lie?". The Conversation. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Amazing! Bird sounds from the lyrebird - David Attenborough - BBC Wildlife". BBC Studios, YouTube. YouTube. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- National Film and Sound Archive: Sounds of Australia.

- Powys, Vicki; Taylor, Hollis; Probets, Carol (2013). "A little flute music: mimicry, memory, and narrativity". Environmental Humanities. 3 (1): 43–70. doi:10.1215/22011919-3611230. ISSN 2201-1919.

- Nungent, D.T. (2014). "Interactions between the superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) and fire in south-eastern Australia". Wildlife Research. 41 (3): 203–211. doi:10.1071/WR14052.

- Kenyon, R.F. (1972). "Polygyny among superb lyrebirds in Sherbrooke Forest Park". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 72: 70–76. doi:10.1071/MU972070.

- "Ten Cents". Royal Australian Mint. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- "NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service". Retrieved 6 June 2019.

Further reading

Smith, L. H. (1988). The Life of the Lyrebird. William Heinemann Australia. ISBN 0-85561-122-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Menura novaehollandiae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Menura novaehollandiae |

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- Superb lyrebird - Museum Victoria

- Superb lyrebird - Dr. Ellen Rudolph

- Superb lyrebird photo and information - Sherbrooke Lyrebird Survey Group

- Photos, audio and video of superb lyrebird from Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Macaulay Library