Order (biology)

In biological classification, the order (Latin: ordo) is

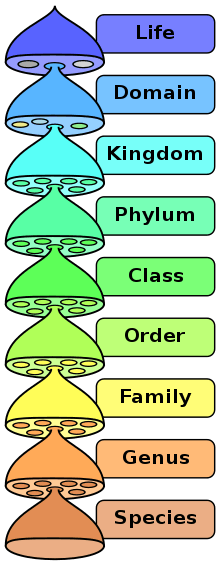

- a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized by the nomenclature codes. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, family, genus, and species, with order fitting in between class and family. An immediately higher rank, superorder, may be added directly above order, while suborder would be a lower rank.

- a taxonomic unit, a taxon, in that rank. In that case the plural is orders (Latin ordines).

- Example: All owls belong to the order Strigiformes

What does and does not belong to each order is determined by a taxonomist, as is whether a particular order should be recognized at all. Often there is no exact agreement, with different taxonomists each taking a different position. There are no hard rules that a taxonomist needs to follow in describing or recognizing an order. Some taxa are accepted almost universally, while others are recognised only rarely.[1]

For some groups of organisms, consistent suffixes are used to denote that the rank is an order. The Latin suffix -(i)formes meaning "having the form of" is used for the scientific name of orders of birds and fishes, but not for those of mammals and invertebrates. The suffix -ales is for the name of orders of plants, fungi, and algae.[2] The name of an order is usually written with a capital letter.[3]

Hierarchy of ranks

Zoology

For some clades covered by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a number of additional classifications are sometimes used, although not all of these are officially recognised.

| Name | Meaning of prefix | Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnorder | magnus: large, great, important | Boreoeutheria | |

| Superorder | super: above | Euarchontoglires | Parareptilia |

| Grandorder | grand: large | Euarchonta | |

| Mirorder | mirus: wonderful, strange | Primatomorpha | |

| Order | Primates | Procolophonomorpha | |

| Suborder | sub: under | Haplorrhini | Procolophonia |

| Infraorder | infra: below | Simiiformes | Hallucicrania |

| Parvorder | parvus: small, unimportant | Catarrhini |

In their 1997 classification of mammals, McKenna and Bell used two extra levels between superorder and order: "grandorder" and "mirorder".[4] Michael Novacek (1986) inserted them at the same position. Michael Benton (2005) inserted them between superorder and magnorder instead.[5] This position was adopted by Systema Naturae 2000 and others.

Botany

In botany, the ranks of subclass and suborder are secondary ranks pre-defined as respectively above and below the rank of order.[6] Any number of further ranks can be used as long as they are clearly defined.[6]

The superorder rank is commonly used, with the ending -anae that was initiated by Armen Takhtajan's publications from 1966 onwards.[7]

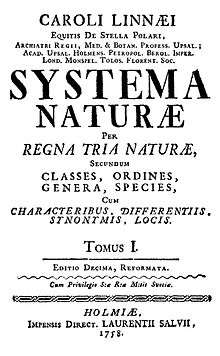

History of the concept

The order as a distinct rank of biological classification having its own distinctive name (and not just called a higher genus (genus summum)) was first introduced by the German botanist Augustus Quirinus Rivinus in his classification of plants that appeared in a series of treatises in the 1690s. Carl Linnaeus was the first to apply it consistently to the division of all three kingdoms of nature (minerals, plants, and animals) in his Systema Naturae (1735, 1st. Ed.).

Botany

For plants, Linnaeus' orders in the Systema Naturae and the Species Plantarum were strictly artificial, introduced to subdivide the artificial classes into more comprehensible smaller groups. When the word ordo was first consistently used for natural units of plants, in 19th century works such as the Prodromus of de Candolle and the Genera Plantarum of Bentham & Hooker, it indicated taxa that are now given the rank of family (see ordo naturalis, natural order).

In French botanical publications, from Michel Adanson's Familles naturelles des plantes (1763) and until the end of the 19th century, the word famille (plural: familles) was used as a French equivalent for this Latin ordo. This equivalence was explicitly stated in the Alphonse De Candolle's Lois de la nomenclature botanique (1868), the precursor of the currently used International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.

In the first international Rules of botanical nomenclature from the International Botanical Congress of 1905, the word family (familia) was assigned to the rank indicated by the French "famille", while order (ordo) was reserved for a higher rank, for what in the 19th century had often been named a cohors[9] (plural cohortes).

Some of the plant families still retain the names of Linnaean "natural orders" or even the names of pre-Linnaean natural groups recognised by Linnaeus as orders in his natural classification (e.g. Palmae or Labiatae). Such names are known as descriptive family names.

Zoology

In zoology, the Linnaean orders were used more consistently. That is, the orders in the zoology part of the Systema Naturae refer to natural groups. Some of his ordinal names are still in use (e.g. Lepidoptera for the order of moths and butterflies, or Diptera for the order of flies, mosquitoes, midges, and gnats).

Virology

In virology, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses's virus classification includes fifteen taxa: realm, subrealm, kingdom, subkingdom, phylum, subphylum, class, subclass, order, suborder, family, subfamily, genus, subgenus, and species, to be applied for viruses, viroids and satellite nucleic acids.[10] There are currently fourteen viral orders, each ending in the suffix -virales.[11]

Related

- Biological classification

- Cladistics

- Phylogenetics

- Rank (botany)

- Rank (zoology)

- Systematics

- Taxonomy

- Virus classification

Notes

- Tobin, Allan J.; Dusheck, Jennie (2005). Asking About Life. Boston: Cengage Learning. pp. 403–408. ISBN 978-0-030-27044-4.

- (McNeill et al. 2012 & Article 17.1)

- Translation Bureau (2015-10-15). "Capitalization: Biological Terms". Writing Tips, TERMIUM Plus®. Public Services & Procurement Canada. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- McKenna, M.C. & Bell, S.G. (1997), Classification of Mammals, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6

- Benton, Michael J. (2005). Vertebrate Palaeontology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-63205-637-8.

- (McNeill et al. 2012 & Article 4)

- Naik, V.N. (1984), Taxonomy of Angiosperms, Tata McGraw-Hill, p. 111, ISBN 9780074517888CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th ed.). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius.

- Briquet, J. (1912). Règles internationales de la nomenclature botanique adoptées par le congrès international de botanique de Vienne 1905, deuxième edition mise au point d'après les décisions du congrès international de botanique de Bruxelles 1910; International rules of botanical nomenclature adopted by the International Botanical Congresses of Vienna 1905 and Brussels 1910; Internationale Regeln der botanischen Nomenclatur angenommen von den Internationalen Botanischen Kongressen zu Wien 1905 und Brüssel 1910. Jena: Gustav Fischer. Page 1.

- "ICTV Code. Section 3.IV, § 3.23; section 3.V, §§ 3.27-3.28." International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. October 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "ICTV Taxonomy". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2018. Retrieved Nov 8, 2019.

References

- McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Buck, W.R.; Demoulin, V.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Marhold, K.; Prado, J.; Prud'homme Van Reine, W.F.; Smith, G.F.; Wiersema, J.H.; Turland, N.J. (2012). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011. Regnum Vegetabile 154. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag KG. ISBN 978-3-87429-425-6.