Paleontology in Alaska

Paleontology in Alaska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alaska. During the Late Precambrian, Alaska was covered by a shallow sea that was home to stromatolite-forming bacteria. Alaska remained submerged into the Paleozoic era and the sea came to be home to creatures including ammonites, brachiopods, and reef-forming corals. An island chain formed in the eastern part of the state. Alaska remained covered in seawater during the Triassic and Jurassic. Local wildlife included ammonites, belemnites, bony fish and ichthyosaurs. Alaska was a more terrestrial environment during the Cretaceous, with a rich flora and dinosaur fauna.

.svg.png)

During the early Cenozoic, Alaska had a subtropical environment. The local seas continued to drop until a land bridge connected the state with Asia. Early humans crossed this bridge and remains of contemporary local wildlife such as woolly mammoths often show signs of having been butchered.

More recent Native Americans interpreted local fossils through a mythological lens. The local fossils had attracted the attention of formally trained scientists by the 1830s. Major local finds include the Kikak-Tegoseak Pachyrhinosaurus bonebed. The Pleistocene-aged woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius is the Alaska state fossil.

Prehistory

During the Late Precambrian, Alaska was covered by a shallow sea. This sea was home to bacteria and stromatolites that would later fossilize. Most of the state continued to be submerged by the sea. By this time Alaska was home to brachiopods and trilobites. During the ensuing Ordovician and Silurian a chain of volcanic islands occupied what is now the eastern part of the state. These islands originated as a result of contemporary local tectonism. Coral reefs formed in the seas around these islands. The northern third of Alaska was still covered by seawater from the Devonian to the Permian. Local marine life included ammonites, brachiopods, corals, and gastropods.[1] At least 34 different species of gastropods lived in Alaska during the late Paleozoic. Of these, 9 were completely new to science when first discovered.[2]

During the Triassic, the sea expanded. Northern Alaska was submerged under deep water. Southern Alaska was under a shallow sea. The state's Triassic sea was home to bony fish, ichthyosaurs, and mollusca. Volcanic episodes happened frequently in the state at this time.[1] Volcanism continued into the Jurassic as Alaska experienced a period of relative geologic upheaval. Areas of the state remained inundated by the sea. This sea was home to ammonites and crinoids.[1] In the middle Jurassic most of the mountain ranges characterizing modern Alaska began to form.[3] Alaska's Middle Jurassic Callovian deposits are part of a large geologic region spreading down through Canada and even into the Lower 48 states including Montana, Idaho, North Dakota, Utah and New Mexico.[4] From the mid to late Jurassic, the area now occupied by Snug Harbor was home to a great diversity of marine invertebrates, which left behind a plethora of fossils. Among these were ammonites.[2] Others include belemnites, the gastropod Amberlya, the pelecypods Lima, Oxytoma, and possibly Astarte and Isocyprina.[2]

_-_Mauricio_Ant%C3%B3n.jpg)

Cretaceous Alaska gained additional landmass due to collisions with other tectonic plates. Local mountain building resulted in the formation of the Brooks Range and other topographic features. Some areas of Alaska were covered by the sea and others were dry land.[1] There were at least 5 species of Inoceramus in Alaska during the Cretaceous period. This was a widespread genus in Alaska and its fossil remains have been discovered in hundreds of different places.[5] Other Cretaceous shellfish were preserved at what is now Umiat Mountain.[6] More than 235 species of plants are known to have grown in Alaska during the Cretaceous, most of which were cycads.[7] Their remains are scattered across hundreds of sites. Among the finds were algae, Ampelopsis, conifers, elm, Ficus, a great diversity of hepaticae, laurel, magnolia, oaks, Pinus, Platanus, and sequoias. Invertebrate remains were also found with the plants.[8] Pieces of Cretaceous amber have been found on the shore of Nelson Island, which is located in the Bering Sea.[9] Dinosaurs lived in Alaska during the Cretaceous.[1]

Alaska remained tectonically active into the Cenozoic era. Volcanism produced the Aleutian Islands.[1] During the Eocene, Alaska's plants resembled those today growing in the temperate, subtropical and tropical regions of earth today. Their remains were preserved in locations such as the Alaska Peninsula, Awik, the Cook Inlet's shoreline, Eagle City, Unga Island.[8] Alaska's late Miocene fossil record also documents the state's ancient invertebrates.[6] From the Miocene to the Pliocene, Alaska's land area just about reached its full modern extent.[3] Alaska's late Pliocene fossils record also documents the state's invertebrates of that age.[6] During periods of low sea level a land bridge connected Alaska and Asia, allowing an exchanged of the continents' wildlife. Significant areas of Alaska were covered by glaciers during the Quaternary. Alaska was also the site of continued volcanic activity.[1] In Alaska, Pleistocene mammal remains are often associated with artifacts left by Folsom people.[9] Geologically recent invertebrate fossils are also known from Alaska.[6]

History

Indigenous interpretations

The Quugaarpaq is a tusked monster from Yup'ik folklore reported to burrow underground. Fresh air was said to be deadly for the Quugaarpaq, mere contact with which would cause it to petrify. These stories are based on fossils of Ice Age proboscideans whose buried remains are sometimes discovered eroding out of the sediment during spring in southeastern Alaska. Many other indigenous cultures from around the world have interpreted proboscidean fossils as the remains of colossal burrowing animals.[10]

Scientific research

Since 1836, at least five discoveries of mammoths have been made in Alaska. One of the earliest occurred in 1897 when mammoth bones were discovered in a volcanic cave on St. Paul Island. This location was regarded as so unusual that some researchers had expressed suspicions that the remains were planted there as a practical joke.[9] In 1850, another major paleontological milestone in the state was reached with what was probably the first publication on the state's Tertiary plants.[3] Alaska's Tertiary plant fossils were first discovered in places such as the Alaska Peninsula, the Cook Inlet's shoreline, and Unga Island.[8] Between 1902 and 1908, hundreds of sources for Cretaceous plant fossils were discovered. Among the finds were algae, Ampelopsis, conifers, elm, Ficus, a great diversity of hepaticae, laurel, magnolia, oaks, Pinus, Platanus, and sequoias. Invertebrate remains were also found with the plants.[8] In 1903, several sources of Tertiary plant fossils were discovered between Awik and Eagle City.[8] In the 1930s, several lengthy scientific papers shed even more light on Alaska's Cretaceous flora. As such, Alaska's Cretaceous plants did not receive serious treatment in the scientific literature until 50 years after its Tertiary flora.[3] No more mammoth remains were found until 1952 when a partially fossilized mammoth tooth was discovered. The specimen weighed 3 pounds and 11 ounces while measuring in at 9.75 inches long.[9] In the mid-to-late twentieth century, the University of Michigan sent summer expeditions into Alaska to look for Cenozoic vertebrates, but after three failed attempts they called off the effort.[11]

In 1994, a duck-billed dinosaur was discovered in a quarry being excavated in the middle Turonian Matanuska Formation for road material near the Glenn Highway, about 150 miles northeast of Anchorage.[12] This specimen, dubbed the "Talkeetna Mountains Hadrosaur", was the first associated skeleton of an individual dinosaur in Alaska and originated within a previously unknown source of high-latitude dinosaur fossils.[13] That same fall, paleontologists began excavating the specimen, with further work performed during the summer of 1996.[14] It is currently housed at the University of Alaska Museum.[14] The Talkeetna Mountains paleontologists were able to determine that the Talkeetna Mountains Hadrosaur was a juvenile about 3 meters (10 feet) long,[15] but the specimen did not preserve enough anatomical detail for researchers to tell if it was a hadrosaurid or lambeosaurid.[16]

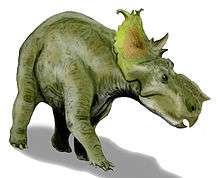

Another 1994 discovery was made by a University of Alaska paleontological survey prospecting along the banks of the Colville River.[17] The team found fossils along the river bank at the base of a bluff that was over 100 meters tall, but could not pinpoint their exact stratigraphic origin on the bluff.[17] In 1997, D. W. Norton and a University of Alaska student named Ron Mancil traced the fossils to the top 3 meters of the bluff.[17] From 1998 to 2002, the Museum of Nature and Science collaborated with the University of Alaska in a typical paleontological excavation of the site, which is now known as the Kikak-Tegoseak Quarry of the Prince Creek Formation.[18] The excavation uncovered a new dinosaur bone bed predominated by the remains of an undetermined species of Pachyrhinosaurus.[19] The United States Army provided assistance to the researchers in 2002.[17] The harsh local climate left the quarry's fossils in a fragmentary state, necessitating that the researchers change their approach to the excavation.[17] After preparing a new approach, workers restarted active excavation in 2005 and stopped at the end of the 2007 field season.[17] The material was removed from the quarry on a sling attached to a U.S. Army Bell 206 Jet Ranger.[17] The fossils are being held at the Museum of Science and Nature.[17]

Natural history museums

- Department of Paleobiology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. [largest collection of Alaskan fossils, mostly legacy collection inherited from USGS]

- Alaska Geologic Materials Center (GMC), Anchorage, Alaska. [extensive collections from oil industry and State Geol. Survey; largest collections of foraminifera and palynomorphs from Alaskan wells]

- Alaska Museum of Natural History, Anchorage

- Alaska State Centennial Museum, Juneau

- University of Alaska Museum of the North, Fairbanks

- Pratt Museum, Homer[20]

Footnotes

- Gangloff, Rieboldt, Scotchmoor, Springer (2006); "Paleontology and geology".

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", page 90.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", page 87.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", pages 91–92.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", pages 89–90.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", page 89.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", pages 87–88.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", page 88.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", page 91.

- Mayor (2005); "The Monsters", pages 123–124.

- Murray (1974); "Alaska", page 92.

- For date and discovery details, see Pasch and May (2001); "Introduction", page 220. For age, see Pasch and May (2001); "Age of the Bone-Bearing Unit", page 220. For location, see Pasch and May (2001); "Location and Geologic Setting", page 220. For origins within the Matanuska Formation, see Pasch and May (2001); "Abstract", page 219.

- Pasch and May (2001); "Abstract", page 219.

- Pasch and May (2001); "Introduction", page 220.

- Pasch and May (2001); "Hadrosaur Skeletal Material from the Talkeetna Mountains", page 223.

- Pasch and May (2001); "Hadrosaur Skeletal Material from the Talkeetna Mountains", pages 223–224.

- Fiorillo, et al. (2010); "Introduction", page 457.

- For excavation information, see Fiorillo, et al. (2010); "Introduction", page 457. For the quarry's position in the Prince Creek Formation, see Fiorillo, et al. (2010); "Geologic Setting", page 457.

- For the quarry's status as a bonebed, see Fiorillo, et al. (2010); "Introduction", page 457. For the identity of the fossils, see Fiorillo, et al. (2010); "Abstract", page 456

- Wild-Eyed Alaska: Gull Island in Kachemak Bay

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Alaska. |

- A. R. Fiorillo, P. J. McCarthy, P. P. Flaig, E. Brandlen, D. W. Norton, P. Zippi, L. Jacobs and R. A. Gangloff. 2010. "Paleontology and paleoenvironmental interpretation of the Kikak-Tegoseak Quarry (Prince Creek Formation: Late Cretaceous), northern Alaska: a multi-disciplinary study of a high-latitude ceratopsian dinosaur bonebed". In M. J. Ryan, B. J. Chinnery-Allgeier, D. A. Eberth (eds.), New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 456–477.

- Flaig, P.P., Fiorillo, A.R., and McCarthy, P.J., 2014, Dinosaur-bearing hyperconcentrated flows of Cretaceous Arctic Alaska—Recurring catastrophic event beds on a distal paleopolar coastal plain: Palaios, v. 29, no. 11, p. 594–611.

- Gangloff, Roland, Sarah Rieboldt, Judy Scotchmoor, Dale Springer. July 21, 2006. "Alaska, US". The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Pasch, A. D., K. C. May. 2001. "Taphonomy and paleoenvironment of hadrosaur (Dinosauria) from the Matanuska Formation (Turonian) in South-Central Alaska". In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Eds. Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press. pp. 219–2