Paleontology in Idaho

Paleontology in Idaho refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Idaho. The fossil record of Idaho spans much of the geologic column from the Precambrian onward.[1] During the Precambrian, bacteria formed stromatolites while worms left behind trace fossils. The state was mostly covered by a shallow sea during the majority of the Paleozoic era. This sea became home to creatures like brachiopods, corals and trilobites. Idaho continued to be a largely marine environment through the Triassic and Jurassic periods of the Mesozoic era, when brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, ichthyosaurs and sharks inhabited the local waters. The eastern part of the state was dry land during the ensuing Cretaceous period when dinosaurs roamed the area and trees grew which would later form petrified wood.

Cenozoic Idaho had a more hospitable climate than it does today and would come to be home to huge forests and creatures like camels, early horses, mastodons, and sloths. During the Pleistocene, short-faced bears, bison, camels, mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths inhabited the state. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. By the dawn of the 20th century, the state's fossils had come to the attention of formally trained scientists. Major local finds include the 1904 discovery of multiple mammoth skeletons and the 1928 discovery of a Pliocene bonebed. The Pliocene Hagerman horse, Equus simplicidens, is the Idaho state fossil.

Prehistory

The earliest fossils of Idaho date back to the Precambrian.[1] However, little is known about Idaho's Precambrian life.[2] Among the few known fossils are trace fossils known as "trails" left by ancient worms burrowing through sediments were preserved in what is now Blackrock Canyon.[1] Fossil stromatolites are also known from the state's southeast.[2] During the early Paleozoic the state was covered by seawater. A wide variety of marine invertebrates live in the state at this time.[2] In the Cambrian, Idaho was home to primitive brachiopods and trilobites.[1] Middle Cambrian sediments in Caribou National Forest document the presence of gastropods at least that far back.[3] Throughout the Silurian and for most of the Devonian Idahoan sea levels dropped, only to rise again and cover most of the state.[2]

The state remained inundated for most of the Carboniferous.[2] During the Carboniferous period, the Arco and Mackay areas were underwater and home to diverse marine wildlife. Most common were corals. Both tabulate and tetracoralla were present in Carboniferous Idaho, and within the tetracoralla were both solitary and colonial forms.[4] The state remained inundated for most of the Permian, when the Paleozoic concluded. Contemporary local vegetation would leave behind fossils and coal deposits on occasion during the Carboniferous and Permian in areas of the state that had been uplifted above the water.[2] In the Permian interesting spiny brachiopods, corals, and fusulinids lived in Idaho's southeastern corner.[4] Idaho continued to be a largely marine environment through the Triassic and Jurassic periods of the Mesozoic era. This sea was home to invertebrates brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, echinoids, molluscs. Vertebrates included ichthyosaurs and sharks. The southeastern part of the state however, was at least occasionally above water.[2]

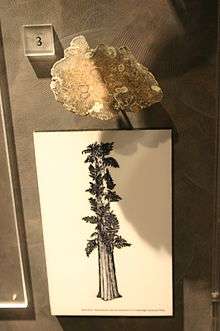

During the Cretaceous, eastern Idaho was host to freshwater and terrestrial habitats. The freshwater environments were inhabited by molluscs and ostracods. Dinosaurs roamed among the vegetation on land.[2] During the Cretaceous, trees were growing southeastern Idaho that would one day be preserved as petrified wood. Among the state's Cretaceous flora, "the most interesting" was the fern Tempskya.[4] Local dinosaurs included possible armored dinosaurs, relatives of the horned dinosaurs, and possibly Tenontosaurus. Dinosaur eggs are also known from the state.[5] Significant volcanic activity occurred in Idaho during the Cretaceous.[6]

Into the Cenozoic, Idaho probably had a more hospitable climate than it does today. Volcanic activity was occurring in the state.[2] During the Oligocene plants were growing near Salmon that would later be preserved as leaf imprints in great abundance. Like the state's Oligocene plants, its Miocene flora left behind abundant leaf imprints in near Coeur d'Alene and Moscow in the northern panhandle.[4] During the ensuing Miocene epoch the northwestern United States was under an immense forest where beech, cypress, oak, and redwood used to grow. Volcanic activity covered 200,000 square miles of the northwest in lava. Some of these trees were carbonized and preserved by the lava along Santa Creek not far from Emida.[7]

The Pliocene plants of the Weiser area also left behind many fossils, although these were generally leaf impressions.[4] During the late Pliocene, Idaho was home to the horse Plesippus soshonensis. This species is regarded as a transitional form between the primitive Pliohippus and the modern horse genus Equus. Late Pliocene life of Idaho that was closely associated with water included aquatic birds, beavers, fish, frogs, a muskrat-like rodent, otters, and turtles. Idaho's late Pliocene life which preferred drier habitats included camels, cats, hares, mastodons, peccaries, and sloths.[8]

Hundreds of different life forms are known to have inhabited Idaho during the Quaternary.[2] The local molluscs also left behind many fossils during the Pleistocene epoch.[4] Among them were freshwater clams.[8] Oregon's Pleistocene mammals included Equus idahoensis, imperial mammoths, and musk oxen.[8] The Pleistocene mammals of Idaho's American Falls Lake area included short-faced bears, bison, camels, mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths.[4] Columbian mammoths were also present.[7] Mastodons were trapped in quicksand near Twin Falls.[7] Other Quaternary life included birds, fishes, lizards, rabbits, rodents, mountain sheep, and snakes.[2]

History

Indigenous interpretations

The Nez Perce attribute the Pliocene mammal fossils seen along the Snake River to a massive flood occurring long ago that drowned them. Idaho's Shoshone people also attribute local fossils to large floods occurring in the past. Modern paleontology has since found evidence that large scale flooding events occurred 3 million years ago and 15,000 years ago. Remains of animals drowned in these floods can be seen at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument.[9]

Scientific research

Significant Idahoan fossil discoveries occurred early in the 20th century. In 1904, several mammoth skeletons were found in a pocket of sand contained with a spring pool located on the east side of the river at American Falls. One spectacular tusk found amidst the bones was fifteen inches in diameter at its base and stretched over fifteen feet long. These remains were shipped to diverse institutions including at the state capital in Boise, the University of Iowa, and the Smithsonian.[7]

Another notable early-20th century find occurred serendipitously at a farm: A farmer named Elmer Cook found a great number of late Pliocene fossils on his land. Dr. Harold recovered hundreds of pounds of fossils from the Cook farm. He sent a selection of the find to the National Museum in 1928. In response, J. W. Gidley and N. H. Boss of the Smithsonian Institution led an expedition to the Cook farm. They dug thirty feet down into the top of a hill and uncovered a great abundance of fossils. Among the most prominent were horse bones including skulls, jaws, and sections of their vertebral columns. The horse preserved here was later found to be a transitional form between the primitive Pliohippus and the modern horse genus Equus. The Idahoan find was called Plesippus soshenensis. Other fossils found at the site included beavers, fish, frogs, turtles, and other animals closely associated with water. These taxa are closely associated with water and hint that the area was a drinking hole. Other fossils include aquatic birds, camels, cats, hares, mastodons, otters, peccaries, and sloths.[8]

Protected areas

Natural history museums

- Idaho Museum of Natural History, Pocatello

- Orma J. Smith Museum, Caldwell

See also

- Paleontology in Montana

- Paleontology in Nevada

- Paleontology in Oregon

- Paleontology in Utah

- Paleontology in Washington

- Paleontology in Wyoming

Footnotes

- Murray (1974); "Idaho", page 128.

- Springer and Scotchmoor (2006); "Paleontology and geology".

- Murray (1974); "Idaho", pages 128-129.

- Murray (1974); "Idaho", page 129.

- Weishampel, et al. (2004); "3.13 Idaho, United States", page 556.

- Everhart (2005); "One Day in the Life of a Mosasaur", page 7.

- Murray (1974); "Idaho", page 131.

- Murray (1974); "Idaho", page 130.

- Mayor (2005); "Thomas Jefferson's Paleontological Inquiries", pages 58-59.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Idaho. |

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Springer, Dale, Judy Scotchmoor. July 21, 2006. "Idaho, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.