Inoceramus

Inoceramus (Greek: translation "strong pot") is an extinct genus of fossil marine pteriomorphian bivalves that superficially resembled the related winged pearly oysters of the extant genus Pteria. They lived from the Early Jurassic to latest Cretaceous.[1][2]

| Inoceramus | |

|---|---|

| |

| A 187 cm (74 in) Inoceramus/Sphenoceramus steenstrupi fossil found on the Nuussuaq Peninsula | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Pteriida |

| Family: | †Inoceramidae |

| Genus: | †Inoceramus Sowerby, 1814 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Taxonomy

The taxonomy of the inoceramids is disputed, with genera such as Platyceramus sometimes classified as subgenus within Inoceramus. Also the number of valid species in this genus is disputed.

Description

Inoceramids had a thick shell paved with "prisms" of calcite deposited perpendicular to the surface, which gave it a pearly luster in life.[3] Most species have prominent growth lines which appear as raised semicircles concentric to the growing edge of the shell. Paleontologists suggest that the giant size of some species was an adaptation for life in the murky bottom waters, with a correspondingly large gill area that would have allowed the animal to survive in oxygen-deficient waters.[3]

Selected species

- Inoceramus aequicostatus † Voronetz 1937

- Inoceramus albertensis † McLearn 1926

- Inoceramus altifluminis † McLearn 1943

- Inoceramus americanus † Walaszczyk & Cobban 2006

- Inoceramus andinus † Wilckens 1907

- Inoceramus anglicus † Woods 1911

- Inoceramus anilis † Pcelinceva 1962

- Inoceramus anomalus † Heine 1929

- Inoceramus anomiaeformis † Feruglio 1936

- Inoceramus apicalis † Woods 1912

- Inoceramus arvanus † Stephenson 1953

- Inoceramus bellvuensis †

- Inoceramus biformis † Tuomey, 1854

- Inoceramus brownei † Marwick 1953

- Inoceramus carsoni † McCoy 1865

- Inoceramus comancheanus †

- Inoceramus constellatus † Woods 1904

- Inoceramus corpulentus † McLearn 1926

- Inoceramus coulthardi † McLearn 1926

- Inoceramus cuvieri † Sowerby 1814

- Inoceramus dakotensis †

- Inoceramus dominguesi † Maury 1930

- Inoceramus dowlingi † McLearn 1931

- Inoceramus dunveganensis † McLearn 1926

- Inoceramus elburzensis † Fantini 1966

- Inoceramus everesti † Oppel 1862

- Inoceramus fibrosus † Meek & Hayden 1857

- Inoceramus formosulus † Voronetz 1937

- Inoceramus fragilis † Haal & Meek 1856

- Inoceramus frechi † Flegel 1905

- Inoceramus galoi † Boehm 1907

- Inoceramus gibbosus †

- Inoceramus ginterensis † Pergament 1966

- Inoceramus glacierensis † Walaszczyk & Cobban 2006

- Inoceramus haast † Hochstetter 1863

- Inoceramus howelli † White 1876

- Inoceramus incelebratus † Pergament 1966

- Inoceramus inconditus † Marwick 1953

- Inoceramus kystatymensis † Koschelkina 1960

- Inoceramus lamarcki † Parkinson 1819

- Inoceramus lateris † Rossi de Gargia & Camacho 1965

- Inoceramus mesabiensis † Bergquist 1944

- Inoceramus morii † Hayami 1959

- Inoceramus multiformis † Pergament 1971

- Inoceramus mytiliformis † Fantini 1966

- Inoceramus nipponicus † Nagao & Matsumoto 1939

- Inoceramus perplexus †

- Inoceramus pictus †

- Inoceramus pontoni † McLearn 1926

- Inoceramus porrectus † Voronetz 1937

- Inoceramus prefragilis † Stephenson 1952

- Inoceramus proximus † Tuomey, 1854

- Inoceramus pseudolucifer † Afitsky 1967

- Inoceramus quenstedti † Pcelinceva 1933

- Inoceramus robertsoni † Walaszczyk & Cobban 2006

- Inoceramus saskatchewanensis † Warren 1934

- Inoceramus selwyni † McLearn 1926

- Inoceramus sokolovi † Walaszczyk & Cobban 2006

- Inoceramus steinmanni † Wilckens 1907

- Inoceramus subdepressus † Meek & Hayden 1861

- Inoceramus tenuirostratus † Meek & Hayden 1862

- Inoceramus triangularis † Tuomey, 1854

- Inoceramus undabundus † Meek & Hayden 1862

- Inoceramus ussuriensis † Voronetz 1937

Distribution

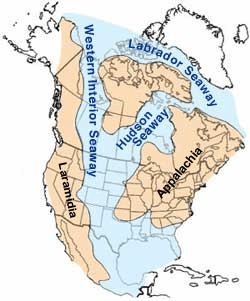

Species of Inoceramus had a worldwide distribution during the Cretaceous and Jurassic periods (from 189.6 to 66.043 Ma).[1] Many examples are found in the Pierre Shale of the Western Interior Seaway in North America. Inoceramus can also be found abundantly in the Cretaceous Gault Clay that underlies London. Other locations for this fossil include Vancouver Island,[3] British Columbia, Colombia (Hiló Formation, Tolima and La Frontera Formation, Boyacá, Cundinamarca and Huila),[4] Spain, France, Germany, Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Antarctica, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada (Alberta, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Saskatchewan, Yukon), Chile, China, Cuba, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greenland, Hungary, India, Indian Ocean, Iran, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Nepal, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Poland, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Serbia and Montenegro, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, the United Kingdom, United States (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wyoming), and Venezuela.[1]

Gallery

Inoceramus from the Cretaceous of South Dakota

Inoceramus from the Cretaceous of South Dakota- Inoceramus proximus

Inoceramus cuvieri

Inoceramus cuvieri Inoceramus vancouverensis

Inoceramus vancouverensis- Inoceramus hobetsensis

References

- Inoceramus at Fossilworks.org

- Ward et al., "Ammonite and inoceramid bivalve extinction patterns in Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary sections of the Biscay region (southwestern France, northern Spain)", Geology, 1991

- Ludvigsen & Beard, 1997, pp.102-103

- Acosta & Ulloa, 2001, p.41

Bibliography

- Ludvigsen, Rolf; Beard, Graham (1997). West Coast Fossils: A Guide to the Ancient Life of Vancouver Island. pp. 102–103.

- Acosta Garay, Jorge; Ulloa Melo, Carlos E (2001). Geología de la Plancha 208 Villeta - 1:100,000 (PDF). INGEOMINAS. pp. 1–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

Further reading

- Kennedy, W.J.; Kauffman, E.G.; Klinger, H.C. (1973). "Upper Cretaceous Invertebrate Faunas from Durban, South Africa". Geological Society of South Africa Transactions. 76 (2): 95–111.

- Klinger, H.C.; Kennedy, W.J. (1980). "Upper Cretaceous ammonites and inoceramids from the off-shore Alphard Group of South Africa". Annals of the South African Museum. 82 (7): 293–320.

- Gebhardt, H. (2001). "Inoceramids, Didymotis and ammonites from the Nkalagu Formation type locakity (late Turonian to Coniacian, southern Nigeria): biostratigraphy and palaeoecologic implications". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 4: 193–212.

- El Qot, G.M. (2006). "Late Cretaceous macrofossils from Sinai, Egypt". Beringeria. 36: 3–163.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inoceramus. |