Paleontology in Wyoming

Paleontology in Wyoming includes research into the prehistoric life of the U.S. state of Wyoming as well as investigations conducted by Wyomingite researchers and institutions into ancient life occurring elsewhere. The fossil record of the US state of Wyoming spans from the Precambrian to recent deposits. Many fossil sites are spread throughout the state.[1] Wyoming is such a spectacular source of fossils that author Marian Murray noted in 1974 that "[e]ven today, it is the expected thing that any great museum will send its representatives to Wyoming as often as possible."[2] Murray has also written that nearly every major vertebrate paleontologist in United States history has collected fossils in Wyoming.[1] Wyoming is a major source of dinosaur fossils.[1] Wyoming's dinosaur fossils are curated by museums located all over the planet.[2]

During the Precambrian, Wyoming was covered by a shallow sea inhabited by stromatolite-forming bacteria. This sea remained in place during the early Paleozoic era and would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, ostracoderms, and trilobites. During the Silurian, the sea withdrew from Wyoming and there is a gap in the local rock record. During the Devonian the sea returned to the state and remained until the Permian when it started to withdraw once more. By the Triassic the state had become a coastal plain inhabited by dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize. By the Jurassic, the state was covered in sand dunes. The Western Interior Seaway submerged much of the state during the Late Cretaceous.

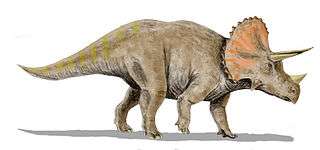

During the early part of the Cenozoic, Wyoming was home to massive lakes inhabited by fish-like Knightia and dense forests. On land the state would come to be inhabited by camels, carnivorans, creodonts, the seven foot tall flightless bird Diatryma, elephants, horses, primates, rodents, and Uintatherium. During the Ice Age, Wyoming was subject to glacial activity. Local Native Americans have known about fossils for thousands of years and have both applied them to practical purposes and devised myths to explain them. Wyoming first became a hotspot for dinosaur research in the 1870s with the discovery of the dinosaurs preserved in the Morrison Formation. By the early 20th century, hundreds of tons of dinosaur fossils had been excavated from Wyoming. The Eocene fish Knightia is the Wyoming state fossil. Triceratops is the state dinosaur of Wyoming.

Prehistory

During the Precambrian, Wyoming was covered by a shallow sea. Stromatolites formed there.[3] Some Precambrian stromatolites remain preserved in the Medicine Bow Mountains.[4] Some local geologic structures may be a record of the activities of other inhabitants of this sea preserved as trace fossils.[3] During the early part of the Paleozoic, Wyoming was still covered by a shallow sea. The state was home to brachiopods and trilobites at this time.[3] By the Late Cambrian, Wyoming was home to calcareous algae. Great masses of this algae were preserved in the Gros Ventre Formation. The area of Wyoming now characterized by the Bighorn Mountains was a marine environment during the Ordovician. Ostracoderms swam in this sea.[4] During the Silurian, the sea withdrew from Wyoming and local sediments were eroded away. During the Devonian, the sea returned to the state and remained until the Permian when it started to withdraw once more.[3]

During the Triassic, Wyoming's sea continued its withdrawal. As the sea shrunk away, much of Wyoming was occupied by a coastal plain environment divided by rivers.[3] During the Late Triassic,[5] dinosaurs left behind small footprints in western Wyoming that would later fossilize. These tracks have been referred to the ichnospecies Agialopus wyomingensis.[6] Some Triassic red beds in Wyoming preserve unusual "scrape mark" trace fossils that were likely left by a swimming animal. Similar tracks found in France have been attributed to turtles.[7] Into the Jurassic, much of the state was covered in sand dunes. Sea levels began to fluctuate again during the Jurassic. The sea was home to belemnites and oysters. On land dinosaurs left behind many footprints across the floodplains.[3] During the Jurassic, the area of Wyoming now called Dinosaur Canyon was home to primitive relatives of modern crocodilians and mammals.[4] Pterosaurs may have been responsible for footprints laid down in sediments now known as the Sundance Formation.[8] They are classified in the ichnogenus Pteraichnus.[9] During the Cretaceous the state experienced an interval of mountain building activity called the Laramide Orogeny.[3] Most of Wyoming was submerged under a sea called the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous.[10] One common inhabitant of Wyoming's Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway was Enchodus. Enchodus was a relative of modern salmon and its long fangs earned it the misleading nickname "the sabre-toothed herring". Although dangerous looking, these fangs were likely used to trap small prey rather than pierce large game. Enchodus was so abundant that roughly one quarter of the fossils left in the state's Pierre Shale deposits are attributable to the genus.[11] Enchodus was preyed upon by Cimolichthys.[12] Cimolichthys was another relative of modern salmon, but had a build similar to that of a barracuda or pike.[13] Cimolichthys was a fierce predator that hunted relatively large game. Sometimes its attempts to kill overly large prey would be its own doom. One Cimolichthys suffocated when its would-be prey, a sizable squid called Tusoteuthis longa, was too large to swallow completely and blocked the fish's gills. Western Interior Seaway researcher Michael J. Everhart has called the specimen "[o]ne of the strangest 'death by gluttony' occurrences in the fossil record".[14] The plesiosaur Dolichorhynchops osborni was another inhabitant of Wyoming's Cretaceous sea. Its remains are more common in this state than in Kansas.[15] The sea turtle Toxochelys latiremis was also present. One specimen was associated with fossil feces preserving fish bones inside. If these feces really belonged to the Toxochelys the inclusion of fish in its diet would distinguish it from all modern sea turtles, none of which are known to eat fish.[16] During the Cretaceous, mammals were common in Wyoming and dinosaurs nested in the area around Powell.[4]Late Cretaceous fossil dinosaur footprints are surprisingly rare in Wyoming compared to other western states with contemporary deposits. This might be due to the local ancient environments not being well suited for track preservation or merely because scientists have not yet looked in the right places.[17]

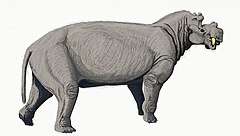

During the early part of the Cenozoic, Wyoming was home to dense forests. Contemporary local vegetation would leave behind significant coal deposits. Massive lakes formed in the low lying areas between local mountains. One inhabitant of these lakes, Knightia eocaena is the state fossil. The Rocky Mountains were still being formed and the local geologic upheaval caused volcanic eruptions.[3] During the Paleocene, the Big Horn Basin was home to a unique mammal fauna.[18] During the Eocene Wyoming contained significant freshwater lakes. The blue-green algae Chlorellopsis grew in this lake. Its fossils are preserved in deposits left around the shores of these lakes. The Green River deposits contain the best preserved freshwater fish fossils in the world not far from Bridger. The seven foot tall flightless bird Diatryma roamed the land. Other land life of Eocene Wyoming include creodonts and a wide variety of insects that left their remains near Henry's Fork, not far from the boundary with neighboring Utah. The Bridger Basin was home to creatures like relatives of camels, carnivorans, elephants, horses, primates, rodents, Uintatherium, and whales.[18] During the Quaternary, volcanic activity continued throughout much of the state and glaciers left significant deposits in the western half of the state.[3]

History

Indigenous interpretations

Evidence for knowledge about fossils among the indigenous peoples of Wyoming stretches at least 11,000 years into the past, as a mammoth kill site of that age located in the Big Horn Basin that contains dinosaur stomach stones. The Clovis people who collected the gastroliths from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation probably intended to use them as hammer stones.[19]

Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus fossils in the Late Cretaceous Lance Creek Formation of Wyoming may have shared responsibility for inspiring Cheyenne myths about a kind of monster called an ahke. Ahke were said to be amphibious creatures resembling giant buffalo. The name derives from "ahk", the Cheyenne word for petrified, as they believed that mineralized bones found on the prairie or weathering out of stream banks are the remains of ahke.[20]

Dinosaur skulls preserved in the Hell Creek or Lance Creek Formations may have inspired another fossil legend.[21] The Hi stowunini hotua, or double-toothed bull is another creature from local Cheyenne mythology that may have been inspired by fossils remains or cultural memories of actual ancient life. The double-toothed bull resembled a buffalo with big sharp incisors on both jaws, as well as sharp horns like a mountain goat. It was a dangerous creature that ate people. The Shoshone of Wyoming were supposedly the last to see it alive and the Cheyenne credited them with its death.[22] Fossils of Oligocene to Miocene age in and around Wyoming are another potential source for the myth. Remains of this interval from the eastern part of the state as well as western Nebraska and South Dakota would have been familiar to the Cheyenne. Relevant fossil wildlife that may have contributed to the double-toothed bull myth include animals large canids, saber-toothed cats, creodonts, oreodonts, or rhinoceroses. Other relevant possible influences include Proceras, a deerlike animal with horns and fangs and entelodonts, large piglike animals with lower incisors as thick as a human wrist.[21] Arctodus simus, the short-faced bear, is a candidate for a possible source of this legend. Arctodus lived from the Pleistocene to the Holocene and is known from the Rocky and Bighorn Mountains region. It may have survived recent enough in the area for cultural memories of encounters with the beast to persist. Its short muzzle and large fangs resemble the description of the double-toothed bull.[22]

Scientific research

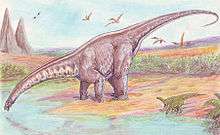

One of the earliest fossil hunting excursions into Wyoming happened in 1870, when O. C. Marsh led an expedition into the state on behalf of Yale.[23] However, the state's abundant dinosaur remains would not come to the attention of science until 1877. Three men played a pivotal early role in bringing scientific attention to the area's dinosaurs. These were Colorado School of Mines professor Arthur Lakes, teacher O. Lucas, and Union Pacific Railroad foreman William H. Reed. Lakes, Lucas, and Reed's preceded many expeditions into Wyoming for the collection of dinosaur fossils.[2] In March 1877, Reed noticed fossil limbs and vertebrae at Como Bluff while returning to the railroad station after hunting. Reed was joined by the railroad station's agent, William E. Carlin. They spent the next several weeks collecting local fossils together but would not tell anyone else about their discovery for months.[24] In July, O. C. Marsh was informed of Reed and Carlin's fossil discoveries at Como Bluff.[25] Marsh hired both of them to acquire more local fossils for him. For the remainder of the year and into early 1878, Reed and Carlin worked on four local quarries. They uncovered several Camarasaurus specimens, one being a new species, Camarasaurus grandis. In May 1878 they discovered a new site for a fifth quarry. There they found the first Jurassic pterosaur known from North America, and a new genus and species of herbivorous dinosaur; Dryosaurus altus. Nearby they made another significant find, Dryolestes priscus, the first Jurassic mammal known from North America.[26] From 1877 to 1878 Princeton also sent a massive expedition to Wyoming. Major participants included Henry Fairfield Osborn, W. E. Scott, and Thomas Speer.[27] Also around this time, Samuel W. Williston began periodic excavations.[2]

Late in 1877, Marsh's scientific rival Edward Drinker Cope heard that fossils had been discovered at Como Bluff. He quickly dispatched his own fossil hunters into the area. Reed described his struggles to keep Cope's men away from his own hunting grounds in regular correspondence with Marsh. William Carlin quit working for Marsh and ended up joining Cope's efforts in the region. Since Carlin was in charge of the railway's station house he used his influence to keep Reed out. Paleontologist John Foster described Reed as "stuck boxing his material for shipment to Marsh outside in the cold." Marsh hired additional help for Reed, but none of his workers stayed on the job long term. Reed was essentially on his own by the spring of 1879, working hectically at excavating several quarries at once to recover the fossils before Cope's men.[26] In the middle of May that same year Marsh directed Arthur Lakes to leave the Morrison, Colorado area and assist Reed at Como Bluff. The partnership would be fruitful that year and several major discoveries happened. They found a site for a seventh quarry and excavated a small ornithopod's skeleton. They found a ninth site early in July that would be one of the best sources of Jurassic mammal fossils anywhere on earth. In terms of absolute numbers Quarry 9 was the most productive of any fossil site in the Morrison Formation.[28]

In September, they made another major discovery.[28] By the end of the month, they had discovered a new species of sauropod, Brontosaurus excelsus, that would end up mounted in the Yale Peabody Museum.[29] This species has since been reclassified as Apatosaurus excelsus. In August William Reed's assistant, E. G. Ashley discovered a twelfth quarry site. They discovered the fossils of a new Stegosaurus species here, S. ungulatus.[30] In September they discovered a thirteenth quarry that produced more dinosaur skeletons than any of the others. Camptosaurus and Stegosaurus were the most common. New dinosaurs discovered here included Camarasaurus lentus, Camptosaurus dispar, and Coelurus fragilis.[31] During the next year Marsh's men focused on quarries thirteen and nine. Later in the year, Arthur Lakes quit. During the next year Reed's brother came to visit, but died while swimming in a nearby creek. After his brother's death Reed lost his enthusiasm for working at Como Bluff. He quit altogether by the spring of 1883. From then on Marsh's operations at Como Bluff were led by E. G. Kennedy and Fred Brown. They continued the previous leadership's emphasis on quarries 9 and 13. By June 1889, fieldwork at Como Bluff had concluded after twelve years. Marsh's fieldwork in the area uncovered the greatest abundance of Jurassic fossils known in the world at the time.[32] By the 1918 conclusion of Samuel W. Williston's work in Wyoming hundreds of tons of dinosaur bones had been recovered from Wyoming rocks.[2]

Another advancement in Wyoming paleontology occurred in 1932 when Edward Branson and Maurice Mehl reported the discovery of a fossil trackway in Wyoming's Tensleep Sandstone.[33] These tracks were given the ichnospecies Steganoposaurus belli.[33] The tracks were probably made by a web-footed animal slightly less than three feet long.[33] They are similar to the Tridentichnus tracks of the Supai Formation.[34] Later research has suggested that these footprints were left by reptiles similar to Hylonomus rather than amphibians.[35] Support for this hypothesis comes from the track's pointed reptile-like toes.[35] If the tracks had been left by an amphibian they probably would be "blunt [and] rounded".[35] Small dinosaur footprints were also discovered in western Wyoming during the 1930s. They were formally described as Agialopus wyomingensis.[6] They were of Late Triassic age.[5]

In 1940 C. L. Gazin led an expedition into Wyoming on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution. Their biggest find was a nearly complete skeleton of Uintatherium. Fossils of Unitatherium are relatively common, but the specimen uncovered by Gazin's expedition was exceptionally complete and in high quality preservation. The only parts missing from the skeleton were the neck vertebrae, part of one forelimb, and a hindlimb.[18] The fossil was discovered on a steep hillside slope.[36] To remove the remains from their place of preservation, the team had to drive a truck up a dry creek bed and physically drag the remains out on canvas. The fossils were so numerous and massive that they filled four crates, each weighing 500 pounds. After being packaged into the crates the bones were shipped to Washington, D.C.[37]

In 1953, C. L. Gazin led another expedition into Wyoming for the Smithsonian. The crew's excavations in the Bison Basin uncovered the jaws and teeth of at least four species in two genera of plesiadapids, primitive primates related to modern lemurs. Pronothodectes was the largest and most primitive plesiadapid found by the expedition. Primitive "sub-ungulate"s were among the other discoveries made on the expedition. They also found herbivorous condylarth fossils one of these, Phenacodus, was more than four feet long, which makes it unusually large for the group. Lastly, the expedition also found fossils of the carnivorous creodonts and bear-like clenodonts.[18]

More recently, in 1977, Terry Logue reported possible fossil pterosaur footprints from the Sundance Formation in Wyoming.[8] Later, on 18 February 1987 the Eocene fish Knightia was designated the Wyoming state fossil. In 1994 Triceratops was designated the state dinosaur of Wyoming.

Protected areas

People

Walter W. Granger died in Lusk on September 6th, 1941 at age 68.

Natural history museums

- Paleon Museum, Glenrock, Wyoming

- Tate Geological Museum, Casper

- Draper Museum of Natural History, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody

- Natural History Museum of Western Wyoming College, Rock Springs

- University of Wyoming Geological Museum, Laramie

- Wyoming Dinosaur Center, Thermopolis, Wyoming

See also

Footnotes

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", page 293.

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", page 294.

- Springer and Scotchmoor (2010); "Paleontology and geology".

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", page 296.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Figure 3.20", page 95.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Northern Colorado Plateau Region of the Chinle", page 94.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Moenkopi of the Early and Middle Triassic", page 72.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Real Pterosaur Tracks Story", page 160.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Real Pterosaur Tracks Story", pages 159-160.

- Everhart (2005); "One Day in the Life of a Mosasaur", page 5.

- Everhart (2005); "Enchodus and Cimolichthys", page 84.

- Everhart (2005); "Enchodus and Cimolichthys", pages 84-85.

- Everhart (2005); "Enchodus and Cimolichthys", page 86.

- Everhart (2005); "Enchodus and Cimolichthys", page 87.

- Everhart (2005); "Pliosaurs and Polycotylids", page 153.

- Everhart (2005); "Turtles: Leatherback Giants", page 112.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Rare Tracks of the Laramie Formation", page 236.

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", page 297.

- Mayor (2005); "Hopi and Pueblo Fossil Collectors", pages 157-158.

- Mayor (2005); "Cheyenne Fossil Knowledge", pages 211-212.

- Mayor (2005); "Cheyenne Fossil Knowledge", page 213.

- Mayor (2005); "Cheyenne Fossil Knowledge", pages 212-213.

- Everhart (2005); "Pteranodons: Rulers of the Air", page 195.

- Foster (2007); "March 1877", pages 66-67.

- Foster (2007); "Cope and Marsh: The Fuel for the Fire", page 68.

- Foster (2007); "Como Bluff (1877-1889)", page 68.

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", page 295.

- Foster (2007); "Como Bluff (1877-1889)", page 69.

- Foster (2007); "Como Bluff (1877-1889)", pages 69-70.

- Foster (2007); "Como Bluff (1877-1889)", page 70.

- Foster (2007); "Como Bluff (1877-1889)", page 71.

- Foster (2007); "Como Bluff (1877-1889)", page 72.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 34.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", pages 34-35.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 35.

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", pages 297-298.

- Murray (1974); "Wyoming", page 298.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Wyoming. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleontology in the United States#Wyoming |

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- Lockley, Martin and Hunt, Adrian. Dinosaur Tracks of Western North America. Columbia University Press. 1999.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Springer, Dale, Judy Scotchmoor. July 14, 2010. "Wyoming, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.