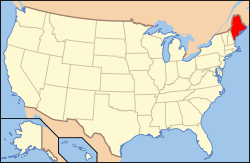

Paleontology in Maine

Paleontology in Maine refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maine. The fossil record of Maine is very sparse.[1] Maine came into existence during the Ordovician as other ancient land masses accreted onto North America. At the time Maine was covered by a sea inhabited by a menagerie of invertebrates which included graptolites. During the Devonian, geologic uplift raised Maine above sea level. Early land plants flourished in the terrestrial environments. There is a gap in the local rock record spanning the remainder of the Paleozoic, the Mesozoic, and the Tertiary period of the Cenozoic era. During the Ice Age, Maine was varyingly covered by glaciers or seawater. The Devonian Pertica plant, Pertica quadrifaria, is the Maine state fossil.

Prehistory

Maine came into existence during the Ordovician as other ancient land masses accreted onto North America. At the time, however, Maine was covered by a sea and located in the southern hemisphere. Large numbers of invertebrates living at a variety of depths inhabited this sea.[2] Ordovician graptolites left fossils behind at a location 100 miles north of Lake Memphremagog but the quality of these remains is usually so low that specimens worthy of collection are uncommon according to author Marian Murray.[3] Remains left behind by Silurian marine life were preserved in the areas of Maine that border what is now New Brunswick, Canada.[4] The fossils are preserved sedimentary deposits within a stratigraphic interval that alternates between the fossil-bearing beds and beds laid down by volcanic activity that are made of lava and volcanic ash.[3] In the Devonian, mountain building began elevating regions of Maine. By this time the state included terrestrial habitats. Deposits from these environments reveal a contemporary flora, although these plant fossils are generally fragmentary. By the end of the Devonian, all of Maine was dry land.[2] For the rest of the Paleozoic, local sediments were being eroded rather than deposited, so no fossils are known from this interval.[2] This erosive interval continued throughout the entire Mesozoic era.[2] As such, no dinosaur fossils have ever been discovered in Maine.[5] Erosion continued from the start of the Cenozoic until the Ice Age. During the Ice Age, Maine was most thoroughly covered in glaciers about 20,000 years ago. Their incredible weight pushed down the land relative to sea level. Consequently seawater began to flood the state as the glaciers retreated. As the state returned to its original elevation relative to sea level it dried out and became terrestrial once again. Local ecosystems gradually became more temperate as temperatures warmed.[2]

Paleontologists from Maine

- Benjamin Franklin Mudge was born in Orrington on August 11, 1817.

- David P. Penhallow was born in Kittery Point on 25 May, 1854.

- Jack Sepkoski was born in Presque Isle on July 26, 1948.

Natural history museums

- George B. Dorr Museum of Natural History, Bar Harbor

- L.C. Bates Museum, Hinckley

- Maine State Museum, Augusta

- Northern Maine Museum of Science, Presque Isle

- The Nylander Museum, Caribou

- Wilson Museum, Castine

See also

Footnotes

- Murray (1974); "Maine", page 153.

- Churchill-Dickson, Springer, Scotchmoor (2010); "Paleontology and geology".

- Murray (1974); "Maine", page 154.

- Murray (1974); "Maine", pages 153-154.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Introduction", page 2.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Maine. |

- Churchill-Dickson, Lisa, Dale Springer, Judy Scotchmoor. September 17, 2010. "Maine, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Weishampel, D.B. & L. Young. 1996. Dinosaurs of the East Coast. The Johns Hopkins University Press.