Paleontology in Alabama

Paleontology in Alabama refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alabama. Pennsylvanian plant fossils are common, especially around coal mines. During the early Paleozoic, Alabama was at least partially covered by a sea that would end up being home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and graptolites. During the Devonian the local seas deepened and local wildlife became scarce due to their decreasing oxygen levels.

Life became more abundant early in the Carboniferous. Later in the period richly vegetated swamps spread across the state. The amphibians that lived there left behind one of the greatest abundance of fossil footprints from this age known anywhere in the world. A gap in the local rock record spanned the Permian period. During the Triassic the state experienced rifting as Pangaea broke apart. Later, during the Cretaceous, the state was again partially submerged by seawater, where marine vertebrates flourished. On land the state was home to subtropical forests. The sea covering southern Alabama remained in place during the early part of the Cenozoic era. Marine invertebrates and primitive whales lived there. The climate cooled and the seas withdrew until the Ice Age when Alabama was home to mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths.

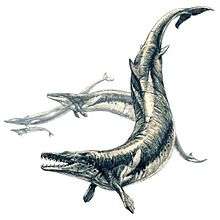

Major fossil discoveries in the state's history include the 1842 discovery of the early whale Basilosaurus, and a later 1961 discovery of more remains from the same species. The Eocene whale Basilosaurus cetoides is the Alabama state fossil.

Prehistory

No Precambrian fossils are known from Alabama. As such, the state's fossil record does not start until the Paleozoic. By the Late Cambrian the state was covered in a warm shallow sea. A rich fauna inhabited this sea. An episode of geologic activity called the Taconic Orogeny uplifted mountains in the state during the Late Ordovician. Sediments eroded away from these mountains are the source of those in the local Ordovician marine deposits.[1] Ordovician life of Alabama included brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and graptolites.[2]

The same erosional and depositional processes continued on through the ensuing Silurian period. During the Devonian period the local seas deepened and their oxygen levels dropped. Fossils from this time period are rare in Alabama because the low oxygen conditions excluded most life forms from the local waters.[1] Life became abundant once more in the local waters during the Mississippian epoch of the Carboniferous period.[1] The name Carboniferous means "coal-bearing". This period has been nicknamed the "age of amphibians" or the "age of coal swamps". During the Mississippian, carbonate rocks were being deposited in the state that would preserve many contemporary life forms as fossils.[3] The Mississippian marine life of Alabama included blastoids, brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and crinoids.[4] Alabama was as swampy as the nickname of the Carboniferous period would suggest from the Late Mississippian into the Pennsylvanian.[5] During the ensuing Pennsylvanian epoch the same sediments eroded from the mountains had formed an expansive coastal plain.[1] The Black Warrior Basin of Alabama preserves evidence for ancient Carboniferous swamps.[5] The rich plant life of these swamps would be preserved in great detail and abundance in the northern part of the state.[5] Early trees and plants resembling ferns grew there. This vegetation left behind great coal deposits.[1] This region also has the largest and most diverse fossil tracksites from this time period in the world.[5] Sediments were eroded away from Alabama rather than deposited during the Permian period, so there are no local rocks from this time period.[1]

Alabama experienced rifting during the Triassic period of the Mesozoic era due to the breakup of Pangaea. The valleys formed by the rifts had filled with seawater by the Jurassic period. During the Late Cretaceous Alabama was partially covered by seawater once more.[1] A wide variety of different animals lived in this sea. The oysters Exogyra and Gryphaea were preserved in great abundance during the Cretaceous period.[6] Cretaceous life also included cephalopods, corals, and gastropods.[7] When Alabama's Mooreville Chalk was deposited the area was home to protostegid turtles and the shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli, which fed on them. Sometimes the shark's feeding activities would leave physical evidence on the turtle's bones that would be preserved when they fossilized.[8] Other Alabama sharks included the genus Squalicorax, which also commonly left behind tooth tips embedded in the bones of animals it fed on. Broken Squalicorax crowns have been found embedded in the bones of mosasaurs and even a young hadrosaur.[9] A type of large, freshwater turtle that lived in Cretaceous Alabama was Bothremys, which may have fed on ancient snails.[10] Sea turtle fossils are also commonly found in the Cretaceous rocks of Alabama and in 2018, a new species of Peritresius was named based on Alabama fossils.[11] Areas of Alabama not covered by seawater were home to subtropical forests.[1] Armored and duckbilled dinosaurs inhabited the state, as did tyrannosauroids. The local dinosaurs also left behind eggs to fossilize.[12]

During most of the Tertiary period of the Cenozoic southern Alabama was covered by the sea. The rest of the state was a coastal plain covered by subtropical forests.[1] Paleocene life in Alabama included pelecypods.[13] Eocene life included echinoids, gastropods, solitary corals, and sharks.[14] Basilosaurus "ruled the seas" of Tertiary Alabama.[15] The Early Tertiary Claiborne Group is well known for preserving silicified Ostrea oysters.[6] Claiborne Group outcrops in the state also preserve fossil flowers and pollen.[16] Oligocene life included discoid foraminiferans.[17] By the Pleistocene the local climate had cooled significantly. Although this was the time of the Ice Age, Alabama was too far south to have glaciers within its own boundaries. The northern half of the state was covered in spruce forests. The southern part of the state included grasslands and forests with a greater variety of trees than those of northern Alabama. Local wildlife included mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths.[1]

History

The process of mining Carboniferous-aged coal to help power the industrial revolution has been responsible for uncovering tracks left at that time by early tetrapods in Alabama. Such discoveries frequently occur when the excavation of coal mines removes the rock underlying the trackway, leaving it exposed on the tunnel's ceiling.[18] In 1842, one of the state's biggest early fossil discoveries occurred, the remains of the primitive whale Basilosaurus.[6] The fossils were discovered on a plantation owned by Judge John Creagh of Clarke County, Alabama. His slaves thought the bones had belonged to one of the fallen angels. Local doctors identified the fossils as belonging to an ancient marine reptile. However, some of the fossils were shipped to Sir Richard Owen in England. Owen realized the bones actually belonged to a whale and tried to rename the creature Zeuglodon.[19] Despite the attempted rename, "Zeuglodon" is still formally known by the name first given to it, Basilosaurus.[15] Herman Melville later discussed this discovery in his famous 1851 novel, Moby Dick.[19]

Alabama's Cretaceous rocks have been studied since at least as far back as 1856. In 1919 additional interest was attracted to the local Cretaceous system when a Professional Paper published by the United States Geological Survey listed at least a dozen local sources of contemporary plant fossils.[17] USGS Professional Paper 112 listed sources of Alabama plant fossils in the vicinities of the following towns: Centerville, Cottondale, Cowikee Creek, Eufaula, Glen Allen, Havana, Mapleville, Sanders Ferry Bluff, Shirleys, Snow Plantation, Soap Hill, Tuscaloosa, and Whites Bluff.[20] These sites have produced at least a hundred different kinds of plant over the ensuing years. However, some of these sites were lost after being submerged in the construction of a lock system on the Warrior River.[17] In July 1961, a fossil discovery occurred that author Marian Murray called "one of the most exciting"[19] in the state's history. A Washington County farmer located not far from Millry uncovered a large fossil vertebra while ploughing. The vertebra was later found to belong to Basilosaurus, the primitive Tertiary whale. Further excavation found that almost all of the animal's skeleton was preserved there. Among the recovered remains were 118 vertebrae, 8 ribs, and a six-foot skull with teeth. The bones were taken to Tuscaloosa for the University of Alabama to be made into a museum exhibit.[19] More recently, in 1984 Basilosaurus cetoides was designated the Alabama state fossil. In 2005, the new tyrannosauroid Appalachiosaurus was named based on local Cretaceous fossils.[21]

Paleontologists

- Truman H. Aldrich resided in Birmingham until his death on April 28, 1932.

- Gorden L. Bell, Jr.

- Scott Brande

- Timothy Abbott Conrad

- James L. Dobie

- Jun A. Ebersole

- Andrew D. Gentry

- Douglas E. Jones

- Caitlin R. Kiernan

- James P. Lamb

- Winifred McGlamery

- Andrew K. Rindsberg

- Herbert Huntingdon Smith

- Eugene Allen Smith

Natural history museums

- Alabama Museum of Natural History, Tuscaloosa

- Anniston Museum of Natural History, Anniston

- Auburn University Museum of Natural History

- Black Belt Museum, University of West Alabama

- McWane Science Center, Birmingham

See also

- Paleontology in Florida

- Paleontology in Georgia

- Paleontology in Mississippi

- Paleontology in Tennessee

Footnotes

- Lacefield, Springer, and Scotchmoor (2005); "Paleontology and geology".

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 79.

- Picconi (2003); "Ancient Seascapes of the Inland Basins: Clear, shallow environments preserved as limestone", page 93.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", pages 79–80.

- Picconi (2003); "Ancient Landscapes of the Inland Basins: Swamp environments preserved as dark shale or siltstone", page 94.

- Picconi (2003); "Ancient Seascapes of the Coastal Plain: Muddy, oxygen-rich environments & Silty-sandy environments preserved as gray shale", page 99.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", pages 80–81.

- Everhart (2005); "Sharks: Sharp Teeth and Shell Crushers", page 49.

- Everhart (2005); "Sharks: Sharp Teeth and Shell Crushers", page 54.

- Everhart (2005); "Turtles: Leatherback Giants", page 112.

- Gentry (2018); "A new species of Peritresius Leidy, 1856 (Testudines: Pan-Cheloniidae) from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Alabama, USA, and the occurrence of the genus within the Mississippi Embayment of North America", PLoS ONE 13(4): e0195651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195651

- Weishampel, et al. (2004); "3.30 Alabama, United States", page 587.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 81.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 82.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 86.

- Picconi (2003); "Terrestrial Environments: Intertidal areas, rivers, lakes, land preserved as sand, silt, clay", page 100.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 83.

- Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 34.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 85.

- Berry (1919); "Fossil Plant Localities", plate 1.

- Carr, Williamson, and Schwimmer (2005); in passim.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Alabama. |

- Berry, Edward Wilber (1919). "Upper Cretaceous floras of the Eastern Gulf region in Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia" (PDF). USGS Professional Papers. 112: 177.

- Carr, T. D.; Williamson, T. E.; Schwimmer, D. R. (2005). "A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (1): 119–143. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0119:angaso]2.0.co;2.

- Everhart, Michael J. (2005). Oceans Of Kansas: A Natural History Of The Western Interior Sea. Life of the Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 322.

- Lacefield, Jim; Springer, Dale; Scotchmoor, Judy (July 1, 2005). "Alabama, US". The Paleontology Portal. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- Lockley, Martin G.; Hunt, Adrian (1995). Dinosaur Tracks and Other Fossil Footprints of the Western United States. Columbia University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0231079266.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Picconi, J. E. (2003). "The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Southeastern U.S.". Ithaca, NY: Paleontological Research Institution. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Picconi, J. E. (2016). Swaby, Andrielle N.; Lucas, Mark D.; Ross, Robert M. (eds.). The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Southeastern US (PDF) (2nd ed.). Ithaca, New York: Paleontological Research Institution. ISBN 978-0-87710-512-1.

- Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Cretaceous, North America)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 574–588. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.