Saint Paul Island (Alaska)

Saint Paul Island (Russian: Остров Святого Павла) is the largest of the Pribilof Islands, a group of four Alaskan volcanic islands located in the Bering Sea between the United States and Russia. The city of St. Paul is the only residential area on the island. The three nearest islands to Saint Paul Island are Otter Island to the southwest, Saint George slightly to the south, and Walrus Island to the east.

St. Paul Island has a land area of 40 square miles (100 km2). St. Paul Island currently has one school (K-12, 100 students), one post office, one bar, one small store, and one church (the Russian Orthodox Sts. Peter and Paul Church), which is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

Geography and geology

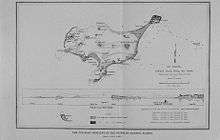

Saint Paul is the largest of the Pribilof Islands and lies the farthest north. With a width of 7.66 mi (12.33 km) at its widest point and a length of 13.5 mi (21.7 km) on its longest axis (which runs from northeast to southwest), it has a total area of 43 sq mi (110 km2). Volcanic in origin, Saint Paul features a number of cinder cones and volcanic craters in its interior. The highest of these, Rush Hill, rises to 665 ft (203 m) on the island's western shore, though most of the upland areas average less than 150 ft (46 m) in elevation. Most of the island is a low-lying mix of rocky plateaus and valleys, with some of the valleys holding freshwater ponds. Much of its 45.5 mi (73.2 km) of shoreline is rugged and rocky, rising to sheer cliffs at several headlands, though long sandy beaches backed by shifting sand dunes flank a number of shallow bays.[1]

Like the other Pribilof Islands, Saint Paul rises from a basaltic base. Its hills are primarily brown or red tufa and cinder heaps, though some (like Polavina) are composed of red scoria and breccia.[2] The island sits on the southern edge of the Bering-Chukchi platform, and may have been part of the Bering Land Bridge's southern coastline when the last ice age's glaciers reached their maximum expansion. Sediment core samples taken on Saint Paul show that tundra vegetation similar to that found on the island today has been present for at least 9,000 years. The thick rough turf is dominated by umbellifers (particularly Angelica) and Artemisia, though grasses and sedges are also abundant.[3]

History

The Aleut peoples knew of the Pribilofs long before westerners discovered the islands. They called the islands Amiq, Aleut for "land of mother's brother" or "related land". According to their oral tradition, the son of an Unimak Island elder found them after paddling north in his boat in an attempt to survive a storm that caught him out at sea; when the winds finally died, he was lost in dense fog—until he heard the sounds of Saint Paul's vast seal colonies.[4][5]

Russian fur traders were the first non-natives to discover Saint Paul. The island was discovered by Gavriil Pribylov on St. Peter and St. Paul's Day, July 12, 1788. Three years later the Russian merchant vessel John the Baptist was shipwrecked off the shore. The crew were listed as missing until 1793, when the survivors were rescued by Gerasim Izmailov.

In the 18th century, Russians forced Aleuts from the Aleutian chain (several hundred miles south of the Pribilofs) to hunt seal for them on the Pribilof Islands. Before this the Pribilofs were not regularly inhabited. The Aleuts were essentially slave labor for the Russians—hunting, cleaning, and preparing fur seal skins, which the Russians sold for a great deal of money. The Aleuts were not taken back to their home islands; they lived in inhumane conditions, they were beaten, and they were regulated by the Russians down to what they could eat and wear and whom they could marry.

Saints Peter and Paul Church, a Russian Orthodox church, was built on the island in 1907.[6]

Climate

Saint Paul's climate is strongly influenced by the cold waters of the surrounding Bering Sea, and is classified as polar (Köppen ET) due to the raw chilliness of the summers. It experiences a relatively narrow range of temperatures, high wind, humidity and cloudiness levels, and persistent summer fog. There is high seasonal lag: February is the island's coldest month, while August is its warmest; the difference between the average low temperature in February and the average high temperature in August is only 31.8 °F (17.7 °C). Although the mean average temperature for the year is above freezing, at 35.33 °F (1.85 °C), the monthly daily average temperature remains below freezing from December to April. Low temperatures at or below 0 °F (−18 °C) occur an average of 4.7 nights per year (mostly from January to March), and the island is part of USDA Hardiness Zone 6.[7] Extreme temperatures have ranged from −19 °F (−28 °C) on March 14, 1971, up to 66 °F (19 °C) on August 25, 1987. Winds are strong and persistent year-round, averaging around 15 mph (24 km/h). They are strongest from late autumn through winter, when they increase to an average of nearly 20 mph (32 km/h), blowing mostly from the north. In the summer, they become weaker and blow primarily from the south.[8]

The island's humidity level, which averages more than 80 percent year round, is highest during the summer. Cloud cover levels peak during the summer as well. Although high year-round, with an average of 88 percent, cloud cover levels rise to 95 percent in the summer. Fog too is more common in the summer, occurring on roughly one-third of the days. The island receives about 23.8 in (605 mm) of precipitation per year, with the highest monthly totals occurring between late summer and early winter, when Bering Sea storms batter the island. Snowfall levels are highest between December and March, averaging 61.7 in (157 cm) per year. Other than trace amounts, the period from June to September is generally snow-free. High winds and relatively warm temperatures combine to keep snow levels low, resulting in monthly mean snow depths of less than 6 in (15 cm). Hours of daylight range from a low of 6.5 hours in midwinter to a high of 18 hours in midsummer.[8]

| Climate data for St Paul Island, Alaska (1981–2010 normals,[9] extremes 1892–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 44 (7) |

42 (6) |

50 (10) |

49 (9) |

59 (15) |

62 (17) |

65 (18) |

66 (19) |

61 (16) |

53 (12) |

48 (9) |

44 (7) |

66 (19) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 38.2 (3.4) |

37.1 (2.8) |

37.9 (3.3) |

40.8 (4.9) |

48.1 (8.9) |

54.2 (12.3) |

57.1 (13.9) |

57.1 (13.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

49.0 (9.4) |

43.4 (6.3) |

40.0 (4.4) |

59.3 (15.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 29.1 (−1.6) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

33.4 (0.8) |

40.4 (4.7) |

46.8 (8.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

49.6 (9.8) |

42.8 (6.0) |

36.9 (2.7) |

33.0 (0.6) |

39.4 (4.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.1 (−3.8) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

29.3 (−1.5) |

36.2 (2.3) |

42.4 (5.8) |

47.2 (8.4) |

48.9 (9.4) |

45.4 (7.4) |

38.6 (3.7) |

33.0 (0.6) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

35.4 (1.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 21.1 (−6.1) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

38.0 (3.3) |

43.6 (6.4) |

45.6 (7.6) |

41.1 (5.1) |

34.4 (1.3) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 3.3 (−15.9) |

1.1 (−17.2) |

3.1 (−16.1) |

9.6 (−12.4) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

36.6 (2.6) |

37.5 (3.1) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

7.7 (−13.5) |

−3.8 (−19.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−16 (−27) |

−19 (−28) |

−8 (−22) |

8 (−13) |

16 (−9) |

28 (−2) |

29 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

12 (−11) |

4 (−16) |

−3 (−19) |

−19 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.58 (40) |

1.30 (33) |

1.07 (27) |

1.08 (27) |

1.13 (29) |

1.35 (34) |

1.85 (47) |

3.07 (78) |

2.99 (76) |

3.11 (79) |

2.89 (73) |

2.25 (57) |

23.67 (601) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.6 (32) |

10.0 (25) |

8.0 (20) |

5.7 (14) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

8.3 (21) |

12.1 (31) |

59.8 (152) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.4 | 15.5 | 14.2 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 12.0 | 13.8 | 17.8 | 19.6 | 22.0 | 23.4 | 21.5 | 203.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 15.2 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 11.0 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 12.8 | 14.9 | 87.3 |

| Source: NOAA[10][11] | |||||||||||||

Natural history

Saint Paul Island, like all of the Pribilof Islands, is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. Its seabird cliffs were purchased in 1982 for inclusion in the refuge.[12] The island has also been designated as an Important Bird Area.[13]

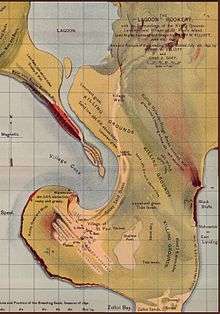

It is the breeding grounds for more than 500,000 northern fur seals and millions of seabirds, and is surrounded by one of the world's richest fishing grounds.

Woolly mammoths survived on Saint Paul Island until around 3,750 BC, which is the most recent survival of North American mammoth populations.[14][15][16][17] It is thought that this population died out as a result of diminishing fresh water, brought on by climate change.[18]

A mass die-off of puffins at St. Paul Island between October 2016 and January 2017 has been attributed to ecosystem changes resulting from global warming.[19]

Population

Saint Paul Island has the largest Aleut community in the United States, one of the U.S. government's officially recognized Native American tribal entities of Alaska. Out of a total population of 532 people, 457 of them (86 percent) are Alaska Natives.[20]

Some of the island's residents only stay part of the year and work in the crab and boat yards. The large boats that have been fishing the Bering Sea offload their fish onto the island and workers prepare them for shipping around the world. The native peoples of the island (Aleut tribe), who make up the vast majority of the population, are Russian Orthodox, if they consider themselves religious.

Wind power

TDX Power's first energy-generation facility was built on St. Paul Island. Completed in 1999, the wind energy-based electric and thermal cogeneration facility was widely regarded as one of the more technologically advanced wind-energy power projects in America. The TDX Power wind/diesel hybrid facility is known for its efficiency and reduction in diesel fuel consumption. The 120-foot (37 m)-tall turbine is a major point of pride for the ecologically conscious Aleut community of Saint Paul.[21] Two additional units were installed in 2007. Each unit is rated at 225 kW[22] and the blade lengths are 44.3 ft (13.5 m).

In popular culture

The island is the scene of the Rudyard Kipling story "The White Seal" and poem "Lukannon" in The Jungle Book.

Media

St. Paul Island is served by KUHB-FM 91.9, an NPR affiliate that broadcasts a wide variety of programming and music. The island also has two low-power translators of the statewide Alaska Rural Communications Service on Channel 4 (K04HM) and Channel 9 (K09RB).

References

- Jordan, David Starr (1898). The Fur Seals and Fur-seal Islands of the North Pacific Ocean. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Treasury: Government Printing Office. p. 31.

- Elliott, Henry W. (1882). A Monograph of the Seal Islands. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 19.

- Hopkins, David Moody, ed. (1967). The Bering Land Bridge. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 224–226. ISBN 978-0-8047-0272-0.

- Borneman 2003, pp. 113–114

- Elliott 1886, pp. 193–194

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-04. Retrieved 2012-07-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Shulski, Martha; Wendler, Gerd (2007). The Climate of Alaska. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-60223-007-1.

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- "Station Name: AK ST PAUL ISLAND AP". National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- "Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge: Wildlife Viewing". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- Cecil, John; Sanchez, Connie; Stenhouse, Iain; Hartzler, Ian (2009). "United States of America" (PDF). In Devenish, C.; Díaz Fernández, D. F.; Clay, R. P.; Davidson, I.; Yépez Zabala, I. (eds.). Important Bird Areas Americas - Priority sites for biodiversity conservation. Quito, Ecuador: BirdLife International. p. 374. ISBN 978-9942-9959-0-2.

- Schirber, Michael. "Surviving Extinction: Where Woolly Mammoths Endured". Live Science. Imaginova Cororporation. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- Kristine J. Crossen, "5,700-Year-Old Mammoth Remains from the Pribilof Islands, Alaska: Last Outpost of North America Megafauna", Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Volume 37, Number 7, (Geological Society of America, 2005), 463.

- David R. Yesner, Douglas W. Veltre, Kristine J. Crossen, and Russell W. Graham, "5,700-year-old Mammoth Remains from Qagnax Cave, Pribilof Islands, Alaska", Second World of Elephants Congress, (Hot Springs: Mammoth Site, 2005), 200–203

- Guthrie, R. Dale (2004-06-17). "Radiocarbon evidence of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Sea island". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 429 (6993): 746–749. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..746D. doi:10.1038/nature02612. PMID 15201907.

- Morelle, Rebecca (August 2, 2016). "Last woolly mammoths 'died of thirst'". BBC News.

- Shankman, Sabrina (2019-05-29). "Mass Die-Off of Puffins Raises More Fears About Arctic's Warming Climate". InsideClimate News. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- St. Paul Island: Blocks 1001 thru 1041, Census Tract 1, Aleutians West Census Area, Alaska United States Census Bureau

- U.S. Department of Energy's interview with Ron Philemonoff of Tanadgusix (TDX) Corporation

- "Commercial Projects". www.tdxpower.com.

Sources

- Borneman, Walter R (2003). Alaska: Saga of a Bold Land. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-050306-8.

- Elliott, Henry Wood (1886). Our Arctic Province: Alaska and the Seal Islands. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Paul Island, Alaska. |