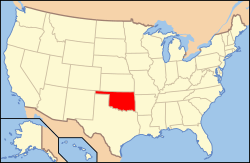

Paleontology in Oklahoma

Paleontology in Oklahoma refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Oklahoma has a rich fossil record spanning all three eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.[1] Oklahoma is the best source of Pennsylvanian fossils in the United States due to having an exceptionally complete geologic record of the epoch.[2] From the Cambrian to the Devonian, all of Oklahoma was covered by a sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, graptolites and trilobites. During the Carboniferous, an expanse of coastal deltaic swamps formed in areas of the state where early tetrapods would leave behind footprints that would later fossilize. The sea withdrew altogether during the Permian period. Oklahoma was home a variety of insects as well as early amphibians and reptiles. Oklahoma stayed dry for most of the Mesozoic. During the Late Triassic, carnivorous dinosaurs left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Cretaceous, however, the state was mostly covered by the Western Interior Seaway, which was home to huge ammonites and other marine invertebrates. During the Cenozoic, Oklahoma became home to creatures like bison, camels, creodonts, and horses. During the Ice Age, the state was home to mammoths and mastodons. Local Native Americans are known to have used fossils for medicinal purposes. The Jurassic dinosaur Saurophaganax maximus is the Oklahoma state fossil.

Prehistory

No Precambrian fossils are known from Oklahoma, and the state's fossil record begins in the Paleozoic.[3] From the Cambrian to the Devonian, Oklahoma was covered by a sea.[3] Cambrian life of Oklahoma included graptolites and trilobites in the area now surrounding Turner Falls in the Arbuckle Mountains, although fossils are relatively scarce.[1] Oklahoma's Ordovician life included several species of brachiopods, bryozoans, primitive echinoderms, and ostracods.[1] Their remains fossilized at Rock Crossing in the Criner Hills of southern Oklahoma. One common Oklahoman graptolite was Climacograptus. High quality specimens of the trilobite Isotelus were preserved southwest of Ardmore.[1] During the Silurian, Oklahoma was home to brachiopods, bryozoans, the trilobite Calymene, echinoderms, and sponges, all of which left their remains south of Lawrence Creek.[4] However, the best sources of Silurian fossils in Oklahoma are "the northern flanks of the Arbuckle Mountains".[1] Oklahoma was home to an extremely diverse Devonian fauna in the Lawrence and White Mound areas.[2]

During the Mississippian, Oklahoma's local fauna included Archimedes, brachiopods, conodonts, echinoderms, the blastoid Pentremites, and trilobites. Contemporary brachiopod families included the productids and rhynchonellida. The best source of Mississippian fossils in Oklahoma is the state's northeastern region.[2] During the Carboniferous, Oklahoma was a terrestrial environment characterized by vast river systems and accompanying deltas. These deltas were home to vast swamps responsible for leaving behind many coal deposits.[3] During the Carboniferous, early tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize.[5] Oklahoma's diverse Pennsylvanian life included blastoids, brachiopods, bryozoans, fusulinids, and pelecypods.[2] Vertebrates included paleoniscid fishes, and the primitive tetrapods responsible for leaving contemporary footprints that would later fossilize.[2] Occasionally during this period, sea levels would rise and cover the state again.[3]

This sea gradually retreated from the state before the end of the Paleozoic era. At this time, Oklahoma was home to amphibians, insects, and reptiles. Footprints laid down at this time would later fossilize.[3] Permian Oklahoma was relatively unchanged from its Pennsylvanian state.[2] Contemporary wildlife of Logan, Noble, Grant, and Garfield Counties included branchiopods, insects, and stegocephalian amphibians.[6] The giant Permian foraminiferan Pseudoschwagerina was preserved in the Pawnee area.[7] Other Permian fossils of Oklahoma were preserved in the north-central region of the state's Kay, Pawnee, and Payne Counties.[2]

Oklahoma was a terrestrial environment for most of the ensuing Mesozoic era.[3] The Late Triassic Dockum Group of western Oklahoma preserved both reptile and amphibian remains, although its fossil record is scanty.[7] During the Late Triassic, small carnivorous dinosaurs left behind tracks near Kenton now classified in the ichnogenus Grallator. The sediments preserving these tracks later became the Sheep Pen Sandstone.[8] Other local tracks have been referred to Chirotherium, but Martin G. Lockley and Adrian Hunt have speculated that these might actually be Pseudotetrasauropus.[9] The Late Jurassic fossiliferous Morrison Formation is exposed in the western part of the state.[7] Most of Oklahoma was submerged under the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous.[10] Early Cretaceous life included "immense" ammonites, echinoids, and pelecypods. These fossils were preserved in Love and Marshall counties. The Late Cretaceous rocks of Bryan, Choctaw, and McCurtain counties bear abundant oysters like Exogyra and Ostraea.[7]

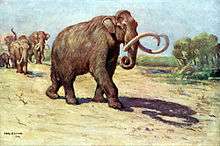

As the Rocky Mountains rose during the early Cenozoic, rivers drained off them and into Oklahoma. Sediments deposited by these rivers would preserve petrified wood and mammal fossils.[3] Sediments were generally being eroded away from Oklahoma during the later portion of the Cenozoic.[3] The High Plains of the western part of Oklahoma preserve evidence for the presence of camels, creodonts, and horses during the Pliocene.[7] During the ensuing Pleistocene epoch, resident animals included mammoths and mastodon. Their fossils were preserved in several different regions of Oklahoma. Typical Oklahoman proboscidean fossils are teeth and tusks, often preserved in gravel pits, but complete skeletons are also known.[7] Other mammals found in Pleistocene Oklahoma included Glyptotherium, a large, heavily armored mammal related to the armadillo.[11]

History

Indigenous interpretations

The Comanche people gathered fossils in Comanche County, near Indiahoma to be used as medicine for sprains and bone fractures. The Comanche ground up the bone into a powder known as tsoapitsitsuhni, which translates to "ghost creature bone", and mixed it with water. This mixture could be made into a sort of plaster cast if the fossils used to make the powder contained sufficient gypsum or calcium sulphate content. The local geology consist largely of Permian-aged red beds, and Comanche County's eastern side contains Richards Spur, the best source of Permian fossils in the entire state.[12] Reptile and amphibian fossils like Captorhinus are found nearby in other counties.[13] Such Permian remains are viable candidates for the fossils used medicinally by the Comanche, but local Jurassic and Cretaceous dinosaur remains like those of Apatosaurus, Saurophaganax, Sauroposeidon and Tenontosaurus are also candidates. More recent mammal fossils were also used by the Comanche for medicine like those of bears, giant bison, camels, glyptodonts, Columbian mammoths, and mastodons. Comanches used bits of mammoth leg bone to draw out boils, infections, poisons and pain from wounds. This usage is fairly plausible as the porous nature of fossil bone causes a capillary effect that could be used to dry infected wounds and sores. Mammoth bone used for this purpose was known as medicinebone or madstone.[14]

Scientific research

In 1931, University of Oklahoma geologist J. W. Stovall received word that a road crew grading for the construction of U.S. Route 64 uncovered a rich deposit of fossils east of Kenton.[15] Stovall examined the site and was impressed by the fossils uncovered by the workers.[16] He organized an expedition to the region. By 1935, Stovall assembled a team consisting of students and a handful of Works Progress Administration workers. He placed a local named Crompton Tate in charge of the team. Stovall's team excavated the site for nearly three years, in the process digging through almost 100 metric tons of rock and sediment to extract the remains preserved there. The site was called Quarry 1, the first of seventeen quarries that the expedition would start in the region. The excavation uncovered the bones from many kinds of dinosaurs.[17] Finds of previously documented species included both sizable and hatchling Apatosaurus, hatchling Camarasaurus, several Camptosaurus of different age groups, and Stegosaurus fossils.[18] The new theropoda species that would come to be known as Saurophaganax was also discovered there.[17]

By December 1939, excavation had commenced on the Stovall team's fifth quarry. The most significant remains uncovered there are referable to the large sauropod Diplodocus. Prior to the cessation of digging at Quarry 5 in the middle of 1941, this quarry had attained impressive dimensions. Its walls were nine meters (30 feet) high and the breadth of the excavation 73 meters (240 feet) wide. Other notable quarries excavated by the Stovall team include the eighth, which produced fossils of ornithopod and theropod dinosaurs as well as other reptiles like a new species of crocodilian, Cteniogenys, and turtles. Lungfish were also preserved there.[19] Funding for Stovall's field work ended with the advent of World War II in 1942, interrupting excavations at Quarries 9 and 10.[19] In 1964, Charles Mook named the new crocodilian species uncovered by the Stovall team Goniopholis stovalli in his honor.[19] The new theropod from Quarry 1 was named Saurophagus. In 1995, Dan Chure published a new name for Saurophagus since that name had already been used for another kind of animal; he renamed it Saurophaganax maximus.[20] More recently, in 2004, Matt Bonnan and Matt Wedel noticed the presence of at least one Brachiosaurus bone among the fossils excavated by the Stovall Crew at Quarry 1.[17]

Natural history museums

- Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman

- The Museum of Osteology, Oklahoma City

See also

Footnotes

- Murray (1974); "Oklahoma", page 234.

- Murray (1974); "Oklahoma", page 235.

- Springer and Scotchmoor (2010); "Paleontology and geology".

- Murray (1974); "Oklahoma", pages 234-235.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 34.

- Murray (1974); "Oklahoma", pages 235-236.

- Murray (1974); "Oklahoma", page 236.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Eastern Region of the Chinle", page 91.

- Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Eastern Region of the Chinle", pages 91-93.

- Everhart (2005); "One Day in the Life of a Mosasaur", page 5.

- "Glyptotherium Osborn 1903 (placental)". Fossilworks. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Mayor (2005); "Comanche Fossil Medicine in Oklahoma", page 195.

- Mayor (2005); "Comanche Fossil Medicine in Oklahoma", pages 195-196.

- Mayor (2005); "Comanche Fossil Medicine in Oklahoma", page 196.

- Foster (2007); "Unit 3: The Oklahoma Panhandle", page 95.

- Foster (2007); "Unit 3: The Oklahoma Panhandle", pages 95-96.

- Foster (2007); "Unit 3: The Oklahoma Panhandle", page 96.

- Foster (2007); "Unit 3: The Oklahoma Panhandle", pages 96-97.

- Foster (2007); "Unit 3: The Oklahoma Panhandle", page 97.

- Foster (2007); "Saurophaganax maximus", page 176.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Oklahoma. |

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- Lockley, Martin and Hunt, Adrian. Dinosaur Tracks of Western North America. Columbia University Press. 1999.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- Springer, Dale, Judy Scotchmoor. July 14, 2010. "Oklahoma, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.