Japan–United States relations

Japan–United States relations (日米関係, Nichibei Kankei) refers to international relations between Japan and the United States. Relations began in the late 18th and early 19th century, with the diplomatic but force-backed missions of U.S. ship captains James Glynn and Matthew C. Perry to the Tokugawa shogunate. The countries maintained relatively cordial relations after that. Potential disputes were resolved. Japan acknowledged American control of Hawaii and the Philippines and the United States reciprocated regarding Korea. Disagreements about Japanese immigration to the U.S. were resolved in 1907. The two were allies against Germany in World War I.

| |

Japan |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Japanese Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Tokyo |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Shinsuke J. Sugiyama | Ambassador William F. Hagerty |

.jpg)

From as early as 1879 and continuing through most of the first four decades of the 1900’s the influential Japanese statesmen, Prince Iyesato Tokugawa (1863-1940) and Baron Eiichi Shibusawa (1840-1931) led a major Japanese domestic and international movement advocating goodwill and mutual respect with the United States. Their friendship with the U.S. included allying with seven U.S. presidents, Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, Harding, Hoover, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It was only after the passing of these two fine Japanese diplomats and humanitarians that Japanese militants were able to pressure Japan into joining with the Axis Powers in WWII. [1] [2]

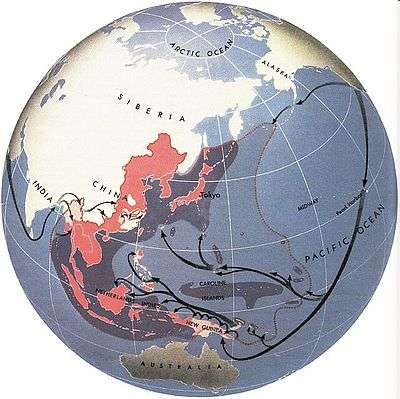

Starting in 1931, tensions escalated. Japanese actions against China in 1931 and especially after 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War caused the United States to cut off the oil and steel Japan required for their military conquests. Japan responded with attacks on the Allies, including the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, which heavily damaged the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, opening the Pacific theater of World War II. The United States made a massive investment in naval power and systematically destroyed Japan's offensive capabilities while island hopping across the Pacific. To force a surrender, the Americans systematically bombed Japanese cities, culminating in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Japan surrendered, and was subjected to seven years of military occupation by the United States, during which the American occupiers under General Douglas MacArthur eliminated the military factor and rebuilt the economic and political systems so as to transform Japan into a democracy.

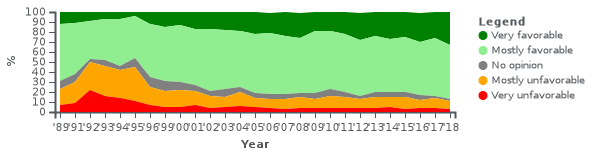

In the 1950s and 1960s Japan, while neutral, grew rapidly by supplying American wars in Korea and Vietnam. The trade relationship has particularly prospered since then, with Japanese automobiles and consumer electronics being especially popular, and Japan became the world's second economic power after the United States. (In 2010 it dropped to third place after China). From the late 20th century and onwards, the United States and Japan have firm and very active political, economic and military relationships. The United States considers Japan to be one of its closest allies and partners.[3][4] Japan is currently one of the most pro-American nations in the world, with 67% of Japanese viewing the United States favorably, according to a 2018 Pew survey;[5] and 75% saying they trust the United States as opposed to 7% for China.[6] Most Americans generally perceive Japan positively, with 81% viewing Japan favorably in 2013, the most favorable perception of Japan in the world.[7]

In recent years, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe has enjoyed good relations with U.S. Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump, with several friendly meetings in the United States and Japan, and other international conferences. In May 2019, President Trump became the first foreign leader to meet the new Emperor Naruhito.

Historical background

Early American expeditions to Japan

- In 1791, two American ships commanded by the American explorer John Kendrick stopped for 11 days on Kii Ōshima island, south of the Kii Peninsula. He is the first American known to have visited Japan. He apparently planted an American flag and claimed the islands, but there is no Japanese account of his visit.[8]

- In 1846, Commander James Biddle, sent by the United States Government to open trade, anchored himself in Tokyo Bay with two ships, one of which was armed with seventy-two cannons. Regardless, his demands for a trade agreement remained unsuccessful.[9]

- In 1848, Captain James Glynn sailed to Nagasaki, which led to the first successful negotiation by an American with sakoku Japan. Upon his return to North America, Glynn recommended to the Congress that any negotiations to open up Japan should be backed up by a demonstration of force; this paved the way for the later expedition of Commodore and lieutenant Matthew Perry.[10]

Commodore Perry opens Japan

In 1852, American Commodore Matthew C. Perry embarked from Norfolk, Virginia, for Japan, in command of a squadron that would negotiate a Japanese trade treaty.[11] Aboard a black-hulled steam frigate, he ported Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and Susquehanna at Uraga Harbor near Edo (present-day Tokyo) on July 8, 1853, and he was met by representatives of the Tokugawa Shogunate. They told him to proceed to Nagasaki, where the sakoku laws allowed limited trade by the Dutch. Perry refused to leave, and he demanded permission to present a letter from President Millard Fillmore, threatening force if he was denied. Japan had shunned modern technology for centuries, and the Japanese military would not be able to resist Perry's ships; these "Black Ships" would later become a symbol of threatening Western technology in Japan.[12] The Dutch behind the scenes smoothed the American treaty process with the Tokugawa shogunate.[13] Perry returned in March 1854 with twice as many ships, finding that the delegates had prepared a treaty embodying virtually all the demands in Fillmore's letter; Perry signed the U.S.- Japan Treaty of Peace and Amity on March 31, 1854, and returned home a hero.[14]

Perry had a missionary vision to bring an American presence to Japan. His goal was to open commerce and more profoundly to introduce Western morals and values. The treaty gave priority to American interests over Japan's. Perry's forceful opening of Japan was used before 1945 to rouse Japanese resentment against the United States and the West; an unintended consequence was to facilitate Japanese militarism.[15]

Townsend Harris (1804–78) served 1856-1861 as the first American diplomat after Perry left.[16] He won the confidence of the Japanese leaders, who asked his advice on how to deal with Europeans. Harris in 1858 obtained the privilege of Americans to reside in Japan's four "open ports" and travel in designated areas. It banned the opium trade and set tariffs. He was the first foreigner to obtain an extended commercial agreement; it was more equitable than the unequal treaties soon obtained by Britain, France and Russia.[17][18]

Pre–World War II period

Japanese embassy to the United States

Seven years later, the Shōgun sent Kanrin Maru on a mission to the United States, intending to display Japan's mastery of Western navigation techniques and naval engineering. On January 19, 1860, Kanrin Maru left the Uraga Channel for San Francisco. The delegation included Katsu Kaishu as ship captain, Nakahama Manjirō and Fukuzawa Yukichi. From San Francisco, the embassy continued to Washington via Panama on American vessels.

Japan's official objective with this mission was to send its first embassy to the United States and to ratify the new Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation between the two governments. The Kanrin Maru delegates also tried to revise some of the unequal clauses in Perry's treaties; they were unsuccessful.

The first American diplomat was consul general Townsend Harris, who was present in Japan from 1856 until 1862 but was denied permission to present his credentials to the Shōgun until 1858. He successfully negotiated the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, or the "Harris Treaty of 1858," securing trade between the two nations and paving the way for greater Western influence in Japan's economy and politics.[19] He was succeeded by Robert H. Pruyn, a New York politician who was a close friend and ally of Secretary of State William Henry Seward. Pruyn served from 1862 to 1865[20] and oversaw successful negotiations following the Shimonoseki bombardment.[21]

From 1865 to 1914

The United States relied on both imported engineers and mechanics, and its own growing base of innovators, while Japan relied primarily on Learning European technology.[22]

In the late 19th century, the opening of sugar plantations in the Kingdom of Hawaii led to the immigration of large numbers of Japanese families. Recruiters sent about 124,000 Japanese workers to more than fifty sugar plantations. China, the Philippines, Portugal and other countries sent an additional 300,000 workers.[23] Hawaii became part of the U.S. in 1898, and the Japanese were the largest element of the population then. Although immigration from Japan largely ended by 1907, they have remained the largest element ever since.

Both countries had ambitions for Hawaii and the Philippines, with the United States taking full ownership of both. The issue was resolved at a high level in 1905 in the Taft–Katsura Agreement, with the United States also Acknowledging Japanese control of Korea.[24] The two nations cooperated with the European powers in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900, but the U.S. was increasingly troubled about Japan's denial of the Open Door Policy that would ensure that all nations could do business with China on an equal basis. President Theodore Roosevelt played a major role in negotiating an end to the war between Russia and Japan in 1905–6.

Vituperative anti-Japanese sentiment (especially on the West Coast) soured relations in the early 20th century.[25] President Theodore Roosevelt did not want to anger Japan by passing legislation to bar Japanese immigration to the U.S. as had been done for Chinese immigration. Instead there was an informal "Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907" between the foreign ministers Elihu Root and Japan's Tadasu Hayashi. The Agreement said Japan would stop emigration of Japanese laborers to the U.S. or Hawaii, and there would not be segregation in California. The agreements remained effect until 1924 when Congress forbade all immigration from Japan—a move that angered Japan.[26][27]

Charles Neu concludes that Roosevelt's policies were a success:

By the close of his presidency it was a largely successful policy based upon political realities at home and in the Far East and upon a firm belief that friendship with Japan was essential to preserve American interests in the Pacific ... Roosevelt's diplomacy during the Japanese-American crisis of 1906-1909 was shrewd, skillful, and responsible.[28]

.jpeg)

In 1912, the people of Japan sent 3,020 cherry trees to the United States as a gift of friendship. First Lady of the United States, Mrs. Helen Herron Taft, and the Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese Ambassador, planted the first two cherry trees on the northern bank of the Tidal Basin. These two original trees are still standing today at the south end of 17th Street. Workmen planted the remainder of the trees around the Tidal Basin and East Potomac Park.[29]

In 1913 the California state legislature proposed the California Alien Land Law of 1913 that would exclude Japanese non-citizens from owning any land in the state. (The Japanese farmers put the title in the names of their American born children, who were U.S. citizens.) The Japanese government protested strongly. Previously, President Taft had managed to halt similar legislation but President Woodrow Wilson paid little attention until Tokyo's protest arrived. He then sent Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan to California; Bryan was unable to get California to relax the restrictions. Wilson did not use any of the legal remedies available to overturn the California law on the basis that it violated the 1911 treaty with Japan. Japan's reaction at both official and popular levels was anger at the American racism that simmered into the 1920s and 1930s.[30][31]

Protestant missionaries

American Protestant missionaries were active in Japan, even though they made relatively few converts. When they returned home, they were often invited to give local lectures on what Japan was really like. In Japan they set up organizations such as colleges and civic groups. Historian John Davidann argues that the evangelical American YMCA missionaries linked Protestantism with American nationalism. They wanted converts to choose "Jesus over Japan". The Christians in Japan, although small minority, held a strong connection to the ancient "bushido" tradition of warrior ethics that undergirded Japanese nationalism. By the 1920s the nationalism theme had been dropped[32] Emily M. Brown and Susan A. Searle were missionaries during the 1880s-1890s. They promoted Kobe College thus exemplifying the spirit of American Progressive reform by concentrating on the education of Japanese women.[33] Similar endeavors included the Joshi Eigaku Jaku, or the English Institute for Women, run by Tsuda Umeko, and the "American Committee for Miss Tsuda's School" under the leadership of Quaker Mary Morris.[34]

World War I and 1920s

During World War I, both nations fought on the Allied side. With the cooperation of its ally the United Kingdom, Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific, and in 1919 after the war, with U.S. approval, was given a League of Nations mandate over the German islands north of the equator, with Australia getting the rest. The U.S. did not want any mandates.[35]

Japan's aggressive role in dealing with China was a continual source of tension—indeed eventually led to World War II between them. In 1917 the Lansing–Ishii Agreement was negotiated. Secretary of State Robert Lansing specified American acceptance that Manchuria was under Japanese control. While still nominally under Chinese sovereignty. Japanese Foreign Minister Ishii Kikujiro noted Japanese agreement not to limit American commercial opportunities elsewhere in China. The agreement also stated that neither would take advantage of the war in Europe to seek additional rights and privileges in Asia.[36]

More trouble arose between Japan on the one hand and China, Britain and the U.S. over Japan's Twenty-One Demands made on China in 1915. These demands forced China to acknowledge Japanese possession of the former German holdings and its economic dominance of Manchuria, and had the potential of turning China into a puppet state. Washington expressed strongly negative reactions to Japan's rejection of the Open Door Policy. In the Bryan Note issued by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan on March 13, 1915, the U.S., while affirming Japan's "special interests" in Manchuria, Mongolia and Shandong, expressed concern over further encroachments to Chinese sovereignty.[37]

President Woodrow Wilson fought vigorously against Japan's demands regarding China at Paris in 1919, but he lost because Britain and France supported Japan.[38] In China there was outrage and anti-Japanese sentiment escalated. The May Fourth Movement emerged as a student demand for China's honor.[39] The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations approved a reservation to the Treaty of Versailles, "to give Shantung to China," but Wilson told his supporters in the Senate to vote against any substantive reservations.[40] In 1922 the U.S. brokered a solution of the Shandong Problem. China was awarded nominal sovereignty over all of Shandong, including the former German holdings, while in practice Japan's economic dominance continued.[41]

Japan and the U.S. agreed on terms of naval limitations at the Washington Conference of 1921, with a ratio of naval force to be 5-5-3 for the U.S., Britain and Japan. Tensions arose with the 1924 American immigration law that prohibited further immigration from Japan.[42]

1929–1937: Militarism and tension between the wars

By the 1920s, Japanese intellectuals were underscoring the apparent decline of Europe as a world power, and increasingly saw Japan as the natural leader for all of East Asia. However, they identified a long-term threat from the colonial powers, especially Britain, the United States, the Netherlands and France, as deliberately blocking Japan's aspirations, especially regarding control of China. The goal became "Asia for the Asians" as Japan began mobilizing anti-colonial sentiment in India and Southeast Asia. Japan took control of Manchuria in 1931 over the strong objections of the League of Nations, Britain and especially the United States. In 1937, it seized control of the main cities on the East Coast of China, over strong American protests. Japanese leaders thought their deeply Asian civilization gave it a natural right to this control and refused to negotiate Western demands that it withdraw from China.[43]

1937–1941

Relations between Japan and the United States became increasingly tense after the Mukden Incident and the subsequent Japanese military seizure of much of China in 1937–39. American outrage focused on the Japanese attack on the US gunboat Panay in Chinese waters in late 1937—Japan apologized after the attack—and the atrocities of the Nanjing Massacre at the same time. The United States had a powerful navy in the Pacific, and it was working closely with the British and the Dutch governments. When Japan seized Indochina (now Vietnam) in 1940–41, the United States, along with Australia, Britain and the Dutch government in exile, boycotted Japan via a trade embargo. They cut off 90% of Japan's oil supply, and Japan had to either withdraw from China or go to war with the US and Britain as well as China to get the oil.

Under the Washington Naval treaty of 1922 and the London Naval treaty, the American navy was to be equal to the Japanese navy by a ratio of 10:6.[44] However, by 1934, the Japanese ended their disarmament policies and enabled rearmament policy with no limitations.[44] The government in Tokyo was well informed of its military weakness in the Pacific in regards to the American fleet. The foremost important factor in realigning their military policies was the need by Japan to seize British and Dutch oil wells.[45]

Through the 1930s, Japan's military needed imported oil for airplanes and warships. It was dependent at 90% on imports, 80% of it coming from the United States.[45] Furthermore, the vast majority of this oil import was oriented towards the navy and the military.[46] America opposed Tokyo's expansionist policies in China and Indochina and, in 1940–41, decided to stop supplying the oil Japan was using for military expansion against American allies. On July 26, 1940 the U.S. government passed the Export Control Act, cutting oil, iron and steel exports to Japan.[45] This containment policy was seen by Washington as a warning to Japan that any further military expansion would result in further sanctions. However, Tokyo saw it as a blockade to counter Japanese military and economic strength. Accordingly, by the time the United States enforced the Export Act, Japan had stockpiled around 54 million barrels of oil.[47] Washington imposed a full oil embargo imposed on Japan in July 1941.[47]

Headed for war

American public and elite opinion—including even the isolationists—strongly opposed Japan's invasion of China in 1937. President Roosevelt imposed increasingly stringent economic sanctions intended to deprive Japan of the oil and steel, as well as dollars, it needed to continue its war in China. Japan reacted by forging an alliance with Germany and Italy in 1940, known as the Tripartite Pact, which worsened its relations with the US. In July 1941, the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands froze all Japanese assets and cut off oil shipments—Japan had little oil of its own.[49]

Japan had conquered all of Manchuria and most of coastal China by 1939, but the Allies refused to recognize the conquests and stepped up their commitment.[50] President Franklin Roosevelt arranged for American pilots and ground crews to set up an aggressive Chinese Air Force nicknamed the Flying Tigers that would not only defend against Japanese air power but also start bombing the Japanese islands.[51]

Diplomacy provided very little space for the adjudication of the deep differences between Japan and the United States. The United States was firmly and almost unanimously committed to defending the integrity of China. The isolationism that characterized the strong opposition of many Americans toward war in Europe did not apply to Asia. Japan had no friends in the United States, nor in Great Britain, nor the Netherlands. The United States had not yet declared war on Germany, but was closely collaborating with Britain and the Netherlands regarding the Japanese threat. The United States started to move its newest B-17 heavy bombers to bases in the Philippines, well within range of Japanese cities. The goal was deterrence of any Japanese attacks to the south. Furthermore, plans were well underway to ship American air forces to China, where American pilots in Chinese uniforms flying American warplanes, were preparing to bomb Japanese cities well before Pearl Harbor.[52][53]

Great Britain, although realizing it could not defend Hong Kong, was confident in its abilities to defend its major base in Singapore and the surrounding Malaya Peninsula. When the war did start in December 1941, Australian soldiers were rushed to Singapore, weeks before Singapore surrendered, and all the Australian and British forces were sent to prisoner of war camps.[54]

The Netherlands, with its homeland overrun by Germany, had a small Navy to defend the Dutch East Indies. Their role was to delay the Japanese invasion long enough to destroy the oil wells, drilling equipment, refineries and pipelines that were the main target of Japanese attacks.

Decisions in Tokyo were controlled by the Army, and then rubber-stamped by Emperor Hirohito; the Navy also had a voice. However the civilian government and diplomats were largely ignored. The Army saw the conquest of China as its primary mission, but operations in Manchuria had created a long border with the Soviet Union. Informal, large-scale military confrontations with the Soviet forces at Nomonhan in summer 1939 demonstrated that the Soviets possessed a decisive military superiority. Even though it would help Germany's war against Russia after June 1941, the Japanese army refused to go north.

The Japanese realized the urgent need for oil, over 90% of which was supplied by the United States, Britain and the Netherlands. From the Army's perspective, a secure fuel supply was essential for the warplanes, tanks and trucks—as well as the Navy's warships and warplanes. The solution was to send the Navy south, to seize the oilfields in the Dutch East Indies and nearby British colonies. Some admirals and many civilians, including Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro, believed that a war with the U.S. would end in defeat. The alternative was loss of honor and power.[55]

While the admirals were dubious about their long-term ability to confront the American and British navies, they hoped that a knockout blow destroying the American fleet at Pearl Harbor would bring the enemy to the negotiating table for a favorable outcome.[56] Japanese diplomats were sent to Washington in summer 1941 to engage in high-level negotiations. However, they did not speak for the Army leadership, which made the decisions. By early October both sides realized that no compromises were possible between the Japan's commitment to conquer China, and America's commitment to defend China. Japan's civilian government fell and the Army under General Tojo took full control, bent on war.[57][58]

World War II

Japan attacked the American navy base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. In response, the United States declared war on Japan. Japan's Axis allies, including Nazi Germany, declared war on the United States days after the attack, bringing the United States into World War II.

_burning_after_the_Japanese_attack_on_Pearl_Harbor_-_NARA_195617_-_Edit.jpg)

_is_hit_by_a_torpedo_on_4_June_1942.jpg)

The conflict was a bitter one, marked by atrocities such as the executions and torture of American prisoners of war by the Imperial Japanese Army and the desecration of dead Japanese bodies. Both sides interred enemy aliens. Superior American military production supported a campaign of island-hopping in the Pacific and heavy bombardment of cities in Okinawa and the Japanese mainland. The strategy was broadly successful as the Allies gradually occupied territories and moved toward the home islands, intending massive invasions beginning in fall 1945. Japanese resistance remained fierce. The Pacific War lasted until September 1, 1945, when Japan surrendered in response to the American atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – among the most controversial acts in military history – and the Soviet entry into the Asian theater of war following the surrender of Germany.

The official Instrument of Surrender was signed on September 2, and the United States subsequently occupied Japan in its entirety.

Post–World War II period

Historian Akira Iriye argues that World War II and the Occupation decisively shaped bilateral relations after 1945. He presents the oil crisis of 1941 as the confrontation of two diametrically opposed concepts of Asian Pacific order. Japan was militaristic, and sought to create and control a self-sufficient economic region in Southeast Asia. Franklin D Roosevelt and his successors were internationalists seeking an open international economic order. The war reflected the interplay of military, economic, political, and ideological factors. The postwar era led to a radical change in bilateral relations from stark hostility to close friendship and political alliance. The United States was now the world's strongest military and economic power. Japan under American tutelage 1945–1951, but then entirely on its own, rejected militarism, embraced democracy and became dedicated to two international policies: economic development and pacifism. Postwar relations between the two countries reached an unprecedented level of compatibility that peaked around 1970. Since then, Japan has become an economic superpower while the United States lost its status as the global economic hegemon. Consequently, their approaches to major issues of foreign policy have diverged. China now is the third player in East Asia, and quite independent of both the United States and Japan. Nevertheless, the strong history of close economic and political relations, and increasingly common set of cultural values continues to provide robust support for continued bilateral political cooperation.[59]

Post–World War II occupation period

At the end of the Second World War, Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers, led by the United States with contributions from Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. This was the first time since the unification of Japan that the island nation had been occupied by a foreign power. The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation, and when it went into effect on April 28, 1952, Japan was once again an independent state, and an ally of the United States. Economic growth in the United States occurred and made the Automobile industry boom in 1946.

1950s: After the occupation

In the years after World War II, Japan's relations with the United States were placed on an equal footing for the first time at the end of the occupation by the Allied forces in April 1952. This equality, the legal basis of which was laid down in the peace treaty signed by forty-eight Allied nations and Japan, was initially largely nominal. A favorable Japanese balance of payments with the United States was achieved in 1954, mainly as a result of United States military and aid spending in Japan.[60]

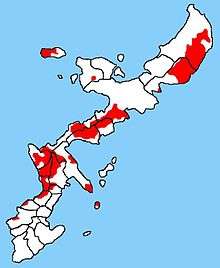

The Japanese people's feeling of dependence lessened gradually as the disastrous results of World War II subsided into the background and trade with the United States expanded. Self-confidence grew as the country applied its resources and organizational skill to regaining economic health. This situation gave rise to a general desire for greater independence from United States influence. During the 1950s and 1960s, this feeling was especially evident in the Japanese attitude toward United States military bases on the four main islands of Japan and in Okinawa Prefecture, occupying the southern two-thirds of the Ryukyu Islands.

The government had to balance left-wing pressure advocating dissociation from the United States allegedly 'against the realities' of the need for military protection. Recognizing the popular desire for the return of the Ryukyu Islands and the Bonin Islands (also known as the Ogasawara Islands), the United States as early as 1953 relinquished its control of the Amami group of islands at the northern end of the Ryukyu Islands. But the United States made no commitment to return Okinawa, which was then under United States military administration for an indefinite period as provided in Article 3 of the peace treaty. Popular agitation culminated in a unanimous resolution adopted by the Diet in June 1956, calling for a return of Okinawa to Japan.

1960s: Military alliance and return of territories

Bilateral talks on revising the 1952 security pact began in 1959, and the new Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security was signed in Washington on January 19, 1960. When the pact was submitted to the Diet for ratification on February 5, it became the subject of bitter debate over the Japan–United States relationship and the occasion for violence in an all-out effort by the leftist opposition to prevent its passage. It was finally approved by the House of Representatives on May 20. Japan Socialist Party deputies boycotted the lower house session and tried to prevent the LDP deputies from entering the chamber; they were forcibly removed by the police. Massive demonstrations and rioting by students and trade unions followed. These outbursts prevented a scheduled visit to Japan by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and precipitated the resignation of Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, but not before the treaty was passed by default on June 19, when the House of Councillors failed to vote on the issue within the required thirty days after lower house approval.[61]

Under the treaty, both parties assumed an obligation to assist each other in case of armed attack on territories under Japanese administration. (It was understood, however, that Japan could not come to the defense of the United States because it was constitutionally forbidden to send armed forces overseas (Article 9). In particular, the constitution forbids the maintenance of "land, sea, and air forces." It also expresses the Japanese people's renunciation of "the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes". Accordingly, the Japanese find it difficult to send their "self-defense" forces overseas, even for peace-keeping purposes.) The scope of the new treaty did not extend to the Ryukyu Islands, but an appended minute made clear that in case of an armed attack on the islands, both governments would consult and take appropriate action. Notes accompanying the treaty provided for prior consultation between the two governments before any major change occurred in the deployment of United States troops or equipment in Japan. Unlike the 1952 security pact, the new treaty provided for a ten-year term, after which it could be revoked upon one year's notice by either party. The treaty included general provisions on the further development of international cooperation and on improved future economic cooperation.

Both countries worked closely to fulfill the United States promise, under Article 3 of the peace treaty, to return all Japanese territories acquired by the United States in war. In June 1968, the United States returned the Bonin Islands (including Iwo Jima) to Japanese administration control. In 1969, the Okinawa reversion issue and Japan's security ties with the United States became the focal points of partisan political campaigns. The situation calmed considerably when Prime Minister Sato Eisaku visited Washington in November 1969, and in a joint communiqué signed by him and President Richard Nixon, announced the United States agreement to return Okinawa to Japan in 1972. In June 1971, after eighteen months of negotiations, the two countries signed an agreement providing for the return of Okinawa to Japan in 1972.[61][62]

The Japanese government's firm and voluntary endorsement of the security treaty and the settlement of the Okinawa reversion question meant that two major political issues in Japan–United States relations were eliminated. But new issues arose. In July 1971, the Japanese government was surprised by Nixon's dramatic announcement of his forthcoming visit to the People's Republic of China. Many Japanese were chagrined by the failure of the United States to consult in advance with Japan before making such a fundamental change in foreign policy. The following month, the government was again surprised to learn that, without prior consultation, the United States had imposed a 10 percent surcharge on imports, a decision certain to hinder Japan's exports to the United States. Relations between Tokyo and Washington were further strained by the monetary crisis involving the December 1971 revaluation of the Japanese yen.

These events of 1971 marked the beginning of a new stage in relations, a period of adjustment to a changing world situation that was not without episodes of strain in both political and economic spheres, although the basic relationship remained close. The political issues between the two countries were essentially security-related and derived from efforts by the United States to induce Japan to contribute more to its own defense and to regional security. The economic issues tended to stem from the ever-widening United States trade and payments deficits with Japan, which began in 1965 when Japan reversed its imbalance in trade with the United States and, for the first time, achieved an export surplus.[61]

Heavy American military spending in the Korean War (1950–53) and the Vietnam War (1965–73) provided a major stimulus to the Japanese economy.[63]

1970s: Vietnam War and Middle-East crisis

The United States withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975 and the end of the Vietnam War meant that the question of Japan's role in the security of East Asia and its contributions to its own defense became central topics in the dialogue between the two countries. American dissatisfaction with Japanese defense efforts began to surface in 1975 when Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger publicly stigmatized Japan. The Japanese government, constrained by constitutional limitations and strongly pacifist public opinion, responded slowly to pressures for a more rapid buildup of its Self-Defense Forces (SDF). It steadily increased its budgetary outlays for those forces, however, and indicated its willingness to shoulder more of the cost of maintaining the United States military bases in Japan. In 1976 the United States and Japan formally established a subcommittee for defense cooperation, in the framework of a bilateral Security Consultative Committee provided for under the 1960 security treaty. This subcommittee, in turn, drew up new Guidelines for Japan-United States Defense Cooperation, under which military planners of the two countries have conducted studies relating to joint military action in the event of an armed attack on Japan.[63][64]

On the economic front, Japan sought to ease trade frictions by agreeing to Orderly Marketing Arrangements, which limited exports on products whose influx into the United States was creating political problems. In 1977 an Orderly Marketing Arrangement limiting Japanese color television exports to the United States was signed, following the pattern of an earlier disposition of the textile problem. Steel exports to the United States were also curtailed, but the problems continued as disputes flared over United States restrictions on Japanese development of nuclear fuel- reprocessing facilities, Japanese restrictions on certain agricultural imports, such as beef and oranges, and liberalization of capital investment and government procurement within Japan.[65]

Under American pressure Japan worked toward a comprehensive security strategy with closer cooperation with the United States for a more reciprocal and autonomous basis. This policy was put to the test in November 1979, when radical Iranians seized the United States embassy in Tehran, taking sixty hostages. Japan reacted by condemning the action as a violation of international law. At the same time, Japanese trading firms and oil companies reportedly purchased Iranian oil that had become available when the United States banned oil imported from Iran. This action brought sharp criticism from the United States of Japanese government "insensitivity" for allowing the oil purchases and led to a Japanese apology and agreement to participate in sanctions against Iran in concert with other United States allies.[66]

Following that incident, the Japanese government took greater care to support United States international policies designed to preserve stability and promote prosperity. Japan was prompt and effective in announcing and implementing sanctions against the Soviet Union following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. In 1981, in response to United States requests, it accepted greater responsibility for defense of seas around Japan, pledged greater support for United States forces in Japan, and persisted with a steady buildup of the SDF.[67]

1980s: Rise of the falcons

A qualitatively new stage of Japan-United States cooperation in world affairs appeared to be reached in late 1982 with the election of Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone. Officials of the Ronald Reagan administration worked closely with their Japanese counterparts to develop a personal relationship between the two leaders based on their common security and international outlook. President Reagan and Prime Minister Nakasone enjoyed a particularly close relationship. It was Nakasone who backed Reagan to deploy Pershing missiles in Europe at the 1983 9th G7 summit. Nakasone reassured United States leaders of Japan's determination against the Soviet threat, closely coordinated policies with the United States toward Asian trouble spots such as the Korean Peninsula and Southeast Asia, and worked cooperatively with the United States in developing China policy. The Japanese government welcomed the increase of American forces in Japan and the western Pacific, continued the steady buildup of the SDF, and positioned Japan firmly on the side of the United States against the threat of Soviet international expansion. Japan continued to cooperate closely with United States policy in these areas following Nakasone's term of office, although the political leadership scandals in Japan in the late 1980s (i.e. the Recruit scandal) made it difficult for newly elected President George H. W. Bush to establish the same kind of close personal ties that marked the Reagan years.

A specific example of Japan's close cooperation with the United States included its quick response to the United States' call for greater host nation support from Japan following the rapid realignment of Japan-United States currencies in the mid-1980s due to the Plaza and Louvre Accords. The currency realignment resulted in a rapid rise of United States costs in Japan, which the Japanese government, upon United States request, was willing to offset. Another set of examples was provided by Japan's willingness to respond to United States requests for foreign assistance to countries considered of strategic importance to the West. During the 1980s, United States officials voiced appreciation for Japan's "strategic aid" to countries such as Pakistan, Turkey, Egypt, and Jamaica. Prime Minister Kaifu Toshiki's pledges of support for East European and Middle Eastern countries in 1990 fit the pattern of Japan's willingness to share greater responsibility for world stability. Another example of US-Japan cooperation is through energy cooperation. In 1983 a US-Japan working group, chaired by William Flynn Martin, produced the Reagan-Nakasone Joint Statement on Japan-United States Energy Cooperation.[68] Other instances of energy relations is shown through the US-Japan Nuclear Cooperation Agreement of 1987 which was an agreement concerning the peaceful use of nuclear energy.[69] Testimony by William Flynn Martin, US Deputy Secretary of Energy, outlined the highlights of the nuclear agreement, including the benefits to both countries.[70]

Despite complaints from some Japanese businesses and diplomats, the Japanese government remained in basic agreement with United States policy toward China and Indochina. The government held back from large-scale aid efforts until conditions in China and Indochina were seen as more compatible with Japanese and United States interests. Of course, there also were instances of limited Japanese cooperation. Japan's response to the United States decision to help to protect tankers in the Persian Gulf during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–88) was subject to mixed reviews. Some United States officials stressed the positive, noting that Japan was unable to send military forces because of constitutional reasons but compensated by supporting the construction of a navigation system in the Persian Gulf, providing greater host nation support for United States forces in Japan, and providing loans to Oman and Jordan. Japan's refusal to join even in a mine-sweeping effort in the Persian Gulf was an indication to some United States officials of Tokyo's unwillingness to cooperate with the United States in areas of sensitivity to Japanese leaders at home or abroad.

The main area of noncooperation with the United States in the 1980s was Japanese resistance to repeated United States efforts to get Japan to open its market more to foreign goods and to change other economic practices seen as adverse to United States economic interests. A common pattern was followed. The Japanese government was sensitive to political pressures from important domestic constituencies that would be hurt by greater openness. In general, these constituencies were of two types—those representing inefficient or "declining" producers, manufacturers, and distributors, who could not compete if faced with full foreign competition; and those up-and-coming industries that the Japanese government wished to protect from foreign competition until they could compete effectively on world markets. To deal with domestic pressures while trying to avoid a break with the United States, the Japanese government engaged in protracted negotiations. This tactic bought time for declining industries to restructure themselves and new industries to grow stronger. Agreements reached dealt with some aspects of the problems, but it was common for trade or economic issues to be dragged out in talks over several years, involving more than one market-opening agreement. Such agreements were sometimes vague and subject to conflicting interpretations in Japan and the United States.

Growing interdependence was accompanied by markedly changing circumstances at home and abroad that were widely seen to have created a crisis in Japan–United States relations in the late 1980s. United States government officials continued to emphasize the positive aspects of the relationship but warned that there was a need for "a new conceptual framework". The Wall Street Journal publicized a series of lengthy reports documenting changes in the relationship in the late 1980s and reviewing the considerable debate in Japan and the United States over whether a closely cooperative relationship was possible or appropriate for the 1990s. An authoritative review of popular and media opinion, published in 1990 by the Washington-based Commission on US-Japan Relations for the Twenty-first Century, was concerned with preserving a close Japan–United States relationship. It warned of a "new orthodoxy" of "suspicion, criticism and considerable self-justification", which it said was endangering the fabric of Japan–United States relations.

The relative economic power of Japan and the United States was undergoing sweeping change, especially in the 1980s. This change went well beyond the implications of the United States trade deficit with Japan, which had remained between US$40 billion and US$48 billion annually since the mid-1980s. The persisting United States trade and budget deficits of the early 1980s led to a series of decisions in the middle of the decade that brought a major realignment of the value of Japanese and United States currencies. The stronger Japanese currency gave Japan the ability to purchase more United States goods and to make important investments in the United States. By the late 1980s, Japan was the main international creditor.

Japan's growing investment in the United States—it was the second largest investor after Britain—led to complaints from some American constituencies. Moreover, Japanese industry seemed well positioned to use its economic power to invest in the high-technology products in which United States manufacturers were still leaders. The United States's ability to compete under these circumstances was seen by many Japanese and Americans as hampered by heavy personal, government, and business debt and a low savings rate.

In the late 1980s, the breakup of the Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe and the growing preoccupation of Soviet leaders with massive internal political and economic difficulties forced the Japanese and United States governments to reassess their longstanding alliance against the Soviet threat. Officials of both nations had tended to characterize the security alliance as the linchpin of the relationship, which should have priority over economic and other disputes. Some Japanese and United States officials and commentators continued to emphasize the common dangers to Japan- United States interests posed by the continued strong Soviet military presence in Asia. They stressed that until Moscow followed its moderation in Europe with major demobilization and reductions in its forces positioned against the United States and Japan in the Pacific, Washington and Tokyo needed to remain militarily prepared and vigilant.

Increasingly, however, other perceived benefits of close Japan-United States security ties were emphasized. The alliance was seen as deterring other potentially disruptive forces in East Asia, notably the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea). Some United States officials noted that the alliance helped keep Japan's potential military power in check and under the supervision of the United States.

21st century: Stronger alliance in the context of a rising China

By the late 1990s and beyond, the US-Japan relationship had been improved and strengthened. The major cause of friction in the relationship, e.g. trade disputes, became less problematic as China displaced Japan as the greatest economic threat to the U.S. Meanwhile, though in the immediate post–Cold War period the security alliance suffered from a lack of a defined threat, the emergence of North Korea as a belligerent rogue state and China's economic and military expansion provided a purpose to strengthen the relationship. While the foreign policy of the administration of President George W. Bush put a strain on some of the United States' international relations, the alliance with Japan became stronger, as evidenced in the Deployment of Japanese troops to Iraq and the joint development of anti-missile defense systems. The notion that Japan is becoming the "Great Britain of the Pacific", or the key and pivotal ally of the U.S. in the region, is frequently alluded to in international studies,[71] but the extent to which this is true is still the subject of academic debate.

In 2009, the Democratic Party of Japan came into power with a mandate calling for changes in the recently agreed security realignment plan and has opened a review into how the accord was reached, claiming the U.S. dictated the terms of the agreement, but United States Defense Secretary Robert Gates said that the U.S. Congress was unwilling to pay for any changes.[72][73][74] Some U.S. officials worried that the government led by the Democratic Party of Japan would maybe consider a policy shift away from the United States and toward a more independent foreign policy.[74]

In 2013 China and Russia held joint naval drills in what Chinese state media called an attempt to challenge the American-Japanese alliance.[75]

On September 19, 2013, Caroline Kennedy sat before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee and responded to questions from both Republican and Democratic senators in relation to her appointment as the US ambassador to Japan. Kennedy, nominated by President Obama in early 2013, explained that her focus would be military ties, trade, and student exchange if she was confirmed for the position.[76]

CIA activities in Japan

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the United States Central Intelligence Agency spent millions of dollars attempting to influence elections in Japan to favor the LDP against more leftist parties such as the Socialists and the Communists,[77][78] although this was not revealed until the mid-1990s when it was exposed by The New York Times.[79]

Economic relations

Trade volume

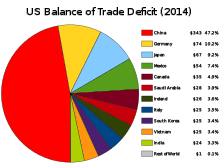

The United States has been Japan's largest economic partner, taking 31.5% of its exports, supplying 22.3% of its imports, and accounting for 45.9% of its direct investment abroad in 1990. As of 2013, the United States takes up 18% of Japanese exports, and supplies 8.5% of its imports (the slack having been picked up by China, which now provides 22%).[80]

Japan's imports from the United States included both raw materials and manufactured goods. United States agricultural products were a leading import in 1990 (US$8.5 billion as measured by United States export statistics), made up of meat (US$1.5 billion), fish (US$1.8 million), grains (US$2.4 billion), and soybeans (US$8.8 billion). Imports of manufactured goods were mainly in the category of machinery and transportation equipment, rather than consumer goods. In 1990 Japan imported US$11.1 billion of machinery from the United States, of which computers and computer parts (US$3.9 billion) formed the largest single component. In the category of transportation equipment, Japan imported US$3.3 billion of aircraft and parts (automobiles and parts accounted for only US$1.8 billion).

Japan's exports to the United States were almost entirely manufactured goods. Automobiles were by far the largest single category, amounting to US$21.5 billion in 1990, or 24% of total Japanese exports to the United States. Automotive parts accounted for another US$10.7 billion. Other major items were office machinery (including computers), which totaled US$8.6 billion in 1990, telecommunications equipment (US$4.1 billion) and power-generating machinery (US$451 million).

From the mid-1960s, the trade balance has been in Japan's favor. According to Japanese data, its surplus with the United States grew from US$380 million in 1970 to nearly US$48 billion in 1988, declining to approximately US$38 billion in 1990. United States data on the trade relationship (which differ slightly because each nation includes transportation costs on the import side but not the export side) also show a rapid deterioration of the imbalance in the 1980s, from a Japanese surplus of US$10 billion in 1980 to one of US$60 billion in 1987, with an improvement to one of US$37.7 billion in 1990.

Trade frictions

Notable outpourings of United States congressional and media rhetoric critical of Japan accompanied the disclosure in 1987 that Toshiba had illegally sold sophisticated machinery of United States origin to the Soviet Union, which reportedly allowed Moscow to make submarines quiet enough to avoid United States detection, and the United States congressional debate in 1989 over the Japan-United States agreement to develop a new fighter aircraft—the FSX—for the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.[81][82]

Direct investment

As elsewhere, Japan's direct investment in the United States expanded rapidly and is an important new dimension in the countries' relationship. The total value of cumulative investments of this kind was US$8.7 billion in 1980. By 1990, it had grown to US$83.1 billion. United States data identified Japan as the second largest investor in the United States; it had about half the value of investments of Britain, but more than those of the Netherlands, Canada, or West Germany. Much of Japan's investment in the United States in the late 1980s was in the commercial sector, providing the basis for distribution and sale of Japanese exports to the United States. Wholesale and retail distribution accounted for 32.2% of all Japanese investments in the United States in 1990, while manufacturing accounted for 20.6%. Real estate became a popular investment during the 1980s, with cumulative investments rising to US$15.2 billion by 1988, or 18.4% of total direct investment in the United States.

Energy

The US and Japan find themselves in fundamentally different situations regarding energy and energy security. Cooperation in energy has moved from conflict (the embargo of Japanese oil was the trigger that launched the Pearl Harbor attack) to cooperation with two significant agreements being signed during the 1980s: the Reagan-Nakasone Energy Cooperation Agreement and the US-Japan Nuclear Cooperation Agreement of 1987 (allowing the Japanese to reprocess nuclear fuels).[83]

Further cooperation occurred during the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami with US troops aiding the victims of the disaster zone and US scientists from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and Department of Energy advising on the response to the nuclear incident at Fukushima. In 2013 the Department of Energy allowed the export of American natural gas to Japan.[84]

Military relations

_and_the_Japan_ship_JS_Kunisaki_(LST_4003)_sail_in_formation_during_a_training_exercise._(48036785657).jpg)

The 1952 Mutual Security Assistance Pact provided the initial basis for the nation's security relations with the United States. The pact was replaced in 1960 by the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, which declares that both nations will maintain and develop their capacities to resist armed attack in common and that each recognizes that an armed attack on either one in territories administered by Japan will be considered dangerous to the safety of the other. The Agreed Minutes to the treaty specified that the Japanese government must be consulted prior to major changes in United States force deployment in Japan or to the use of Japanese bases for combat operations other than in defense of Japan itself. However, Japan was relieved by its constitutional prohibition of participating in external military operations from any obligation to defend the United States if it were attacked outside of Japanese territories. In 1990 the Japanese government expressed its intention to continue to rely on the treaty's arrangements to guarantee national security.[85]

The Agreed Minutes under Article 6 of the 1960 treaty contain a status-of-forces agreement on the stationing of United States forces in Japan, with specifics on the provision of facilities and areas for their use and on the administration of Japanese citizens employed in the facilities. Also covered are the limits of the two countries' jurisdictions over crimes committed in Japan by United States military personnel.

The Mutual Security Assistance Pact of 1952 initially involved a military aid program that provided for Japan's acquisition of funds, matériel, and services for the nation's essential defense. Although Japan no longer received any aid from the United States by the 1960s, the agreement continued to serve as the basis for purchase and licensing agreements ensuring interoperability of the two nations' weapons and for the release of classified data to Japan, including both international intelligence reports and classified technical information.

As of 2014 the United States had 50,000 troops in Japan, the headquarters of the US 7th Fleet and more than 10,000 Marines. In May 2014 it was revealed the United States was deploying two unarmed Global Hawk long-distance surveillance drones to Japan with the expectation they would engage in surveillance missions over China and North Korea.[86] At the beginning of October 2018 the new Japanese Mobile Amphibious Forces held joint exercises with the US marines in the Japanese prefecture of Kagoshima, the purpose of which was to work out the actions in defense of remote territories.[87]

Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa)

Okinawa is the site of major American military bases that have caused problems, as Japanese and Okinawans have protested their presence for decades. In secret negotiations that began in 1969 Washington sought unrestricted use of its bases for possible conventional combat operations in Korea, Taiwan, and South Vietnam, as well as the emergency re-entry and transit rights of nuclear weapons. However anti-nuclear sentiment was strong in Japan and the government wanted the U.S. to remove all nuclear weapons from Okinawa. In the end, the United States and Japan agreed to maintain bases that would allow the continuation of American deterrent capabilities in East Asia. In 1972 the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa, reverted to Japanese control and the provisions of the 1960 security treaty were extended to cover them. The United States retained the right to station forces on these islands.[88]

Military relations improved after the mid-1970s. In 1960 the Security Consultative Committee, with representatives from both countries, was set up under the 1960 security treaty to discuss and coordinate security matters concerning both nations. In 1976 a subcommittee of that body prepared the Guidelines for Japan-United States Defense Cooperation that were approved by the full committee in 1978 and later approved by the National Defense Council and cabinet. The guidelines authorized unprecedented activities in joint defense planning, response to an armed attack on Japan, and cooperation on situations in Asia and the Pacific region that could affect Japan's security.

A dispute that had boiled since 1996 regarding a base with 18,000 U.S. Marines had temporarily been resolved in late 2013. Agreement had been reached to move the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to a less-densely populated area of Okinawa.[89]

National intelligence

Japan's limited intelligence gathering capability and personnel are focused on China and North Korea, as the nation primarily relies on the American National Security Agency.[90]

Public opinion

According to a 2015 Pew survey, 68% of Americans believe that the US can trust Japan, compared to 75% of Japanese who believe that Japan can trust the United States.[92] According to a 2017 Pew survey, 57% of people in Japan had a favorable view of the United States, 75% had a favorable view of the American people, and 24% had confidence in the US president.[93] A 2018 Gallup poll showed that 87% of Americans had a favorable view of Japan.[91]

Historiography

In addition, because World War II was a global war, diplomatic historians start to focus on Japanese–American relations to understand why Japan had attacked the United States in 1941. This in turn led diplomatic historians to start to abandon the previous Euro-centric approach in favor of a more global approach.[94] A sign of the changing times was the rise to prominence of such diplomatic historians such as the Japanese historian Chihiro Hosoya, the British historian Ian Nish, and the American historian Akira Iriye, which was the first time that Asian specialists became noted diplomatic historians.[95] The Japanese reading public has a demand for books about American history and society. They read translations of English titles and Japanese scholars who are Americanists have been active in this sphere.[96]

See also

- Foreign relations of Japan

- Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Black Ships

- Convention of Kanagawa

- Cool Japan, on Japan as superpower

- Internment of Japanese Americans

- Japanese Embassy to the United States (1860)

- Occupation of Japan

- Omoiyari Yosan

- Operation Tomodachi

- Pacific War

- Plaza Accord

- Quadrilateral Security Dialogue

- Security Treaty Between the United States and Japan

- Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

- Treaty of Amity and Commerce (United States–Japan)

- Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan

- Treaty of Portsmouth

- Treaty of San Francisco

- United States beef imports in Japan

- United States Forces Japan

- U.S.–Japan Status of Forces Agreement

- War Plan Orange

- Category:Foreign relations of Bakumatsu Japan (Japanese version)

- Category:Foreign relations of the Empire of Japan (Japanese version)

- Category:Foreign relations of the State of Japan (Japanese version)

References

- "Introduction to The Art of Peace: the illustrated biography of Prince Iyesato Tokugawa". TheEmperorAndTheSpy.com.

- Katz, Stan S. (2019). The Art of Peace: an illustrated biography on Prince Tokugawa Heir to the Last Shogun of Japan. Horizon Productions.

- "Obama: US will stand by longtime ally Japan". The Washington Times. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "Rice says U.S. won't forget Japanese abductees". Reuters. 2008-06-23. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "Japanese views of U.S., Trump". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 2018-11-12. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- "Americans, Japanese: Mutual Respect 70 Years After the End of WWII". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 2015-04-07. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- "Americans Least Favorable Toward Iran; Canada, Great Britain, Germany, and Japan get highest marks". Gallup.com. 2013-03-07.

- Scott Ridley, Morning of Fire: John Kendrick's Daring American Odyssey in the Pacific (2010)

- Spencer C. Tucker, Almanac of American Military History (2012) vol 1 p 682

- Charles Oscar Paullin, American voyages to the Orient, 1690–1865 (1910) p 113

-

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. "Old Bruin": Commodore Matthew C. Perry, 1794-1858: The American naval officer who helped found Liberia, Hunted Pirates in the West Indies, Practised Diplomacy With the Sultan of Turkey and the King of the Two Sicilies; Commanded the Gulf Squadron in the Mexican War, Promoted the Steam Navy and the Shell Gun, and Conducted the Naval Expedition Which Opened Japan (1967) pp 61-76 online free to borrow pp 261-421.

- Francis Hawks, Commodore Perry and the opening of Japan (2005)

- Martha Chaiklin, "Monopolists to Middlemen: Dutch Liberalism and American Imperialism in the Opening of Japan." Journal of World History (2010): 249-269 online.

- George Feifer, Breaking Open Japan: Commodore Perry, Lord Abe, and American Imperialism in 1853 (2013)

- George Feifer, "Perry and Pearl: The unintended consequence." World Policy Journal 24.3 (2007): 103-110 online.

- Tyler Dennett, Americans in Eastern Asia: a critical study of United States' policy in the Far East in the nineteenth century (1922) pp 347-66.

- Walter LaFeber, The Clash: US-Japanese relations throughout history (1998) pp 17-23.

- William Elliot Griffis, Townsend Harris, first American envoy in Japan (1895) online

- William Elliot Griffis (1895). Townsend Harris: First American Envoy in Japan. Sampson Low, Marston.

- Edwin B. Lee "Robert H. Pruyn in Japan, 1862-1865", New York History 66 (1985) pp. 123-39.

- Treat, Payson J. (1928). Japan and the United States, 1853-1921 (2nd ed.). Stanford U.P. pp. 61–63. ISBN 9780804722513.

- John P. Tang, "A tale of two SICs: Japanese and American industrialisation in historical perspective" Australian Economic History Review. (2016) 56#2 pp 174-197.

- Lucie Cheng (1984). Labor Immigration Under Capitalism: Asian Workers in the United States Before World War II. University of California Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780520048294.

- Raymond A. Esthus, "The Taft-Katsura Agreement: Reality or Myth?" Journal of Modern History. 31#1: 46–51. Online

- Raymond Leslie Buell, "The Development of the Anti-Japanese Agitation in the United States," Political Science Quarterly (1922) 37#4 pp. 605–638 part 1 in JSTOR and Buell, "The Development of Anti-Japanese Agitation in the United States II," Political Science Quarterly (1923) 38#1 pp. 57–81 Part 2 in JSTOR

- Carl R. Weinberg, "The 'Gentlemen's Agreement' of 1907–08," OAH Magazine of History (2009) 23#4 pp 36–36.

- A. Whitney Griswold, The Far Eastern Policy of the United States (1938). pp 354–360, 372–379

- Charles E. Neu, An Uncertain Friendship: Theodore Roosevelt and Japan, 1906–1909 (Harvard University Press, 1967), p. 319.

- Rachel Cooper. "Washington, DC's Cherry Trees - Frequently Asked Questions". About. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Herbert P. Le Pore, " Hiram Johnson, Woodrow Wilson, and the California Alien Land Law Controversy of 1913." Southern California Quarterly 61.1 (1979): 99–110. in JSTOR

- Arthur Link, Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era (1954) pp. 84–87

- Jon Thares Davidann, "The American YMCA in Meiji Japan: God's Work Gone Awry." Journal of World History (1995) 6#1: 107-125. online

- Noriko Ishii, “Crossing Boundaries of Womanhood: Professionalization and American Women Missionaries' Quest for Higher Education in Meiji Japan,” Journal of American and Canadian Studies 19 (2001): 85–122.

- Febe D. Pamonag, "Turn-of-the-century cross-cultural collaborations for Japanese women's higher education." US-Japan Women's Journal (2009): 33-56. Online

- Cathal J. Nolan, et al. Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-U.S. Relations during World War I (2000)

- J. Chal Vinson, "The Annulment of the Lansing-Ishii Agreement." Pacific Historical Review (1958): 57-69. Online

- Walter LaFeber, The Clash: US-Japanese Relations Throughout History (1998) pp 106-16

- A. Whitney Griswold, The Far Eastern Policy of the United States (1938) pp 239-68

- Zhitian Luo, "National humiliation and national assertion-The Chinese response to the twenty-one demands," Modern Asian Studies (1993) 27#2 pp 297-319.

- Frederick Lewis Allen (1931), Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s, 2011 reprint, Los Angeles: Indo-European, pp. 18-22, ISBN 978-1-60444-519-0 .

- A. Whitney Griswold, The Far Eastern Policy of the United States (1938) pp 326-28

- Walter Lafeber, The Clash: A History of U.S.-Japan Relations (1997)

- John T. Davidann, "Citadels of Civilization: U.S. and Japanese Visions of World Order in the Interwar Period," in Richard Jensen, Jon Davidann, and Yoneyuki Sugita, eds., Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century (2003) pp 21-44.

- Pelz, Stephen E. Race to Pearl Harbor. Harvard University Press 1974

- Maechling, Charles. Pearl Harbor: The First Energy War. History Today. Dec. 2000

- Hein, Laura E. Fueling Growth. Harvard University Press 1990

- Maechling, Charles. Pearl Harbor: The First Energy War. History Today. December 2000

- This map is at Biennial Reports of the Chief of Staff of the United States Army to the Secretary of War 1 July 1939-30 June 1945 p 156 See full War Department Report

- Conrad Totman, A History of Japan (2005). pp 554–556.

- Herbert Feis, China Tangle: The American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission (1953) contents

- Daniel Ford, Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and His American Volunteers, 1941-1942 (2016).

- Michael Schaller, "American Air Strategy in China, 1939-1941: The Origins of Clandestine Air Warfare" American Quarterly 28#1 (1976), pp. 3-19 in JSTOR

- Martha Byrd, Chennault: Giving Wings to the Tiger (2003).

- S. Woodburn Kirby, The War Against Japan: Volume I: The Loss of Singapore (HM Stationery Office, 195) pp 454-74.

- Haruo Tohmatsu and H. P. Willmott, A Gathering Darkness: The Coming of War to the Far East and the Pacific (2004)

- Dorothy Borg and Shumpei Okamoto, eds. Pearl Harbor as History: Japanese-American Relations, 1931-1941 (1973).

- Herbert Feis, Road to Pearl Harbor: The Coming of the War Between the United States and Japan (1950) pp. 277-78 table of contents

- Michael A. Barnhart, Japan prepares for total war: The search for economic security, 1919–1941 (1987) pp. 234, 262

- Akira Iriye, "Pearl Harbor: A Fifty-Year Perspective" Amerikastudien (1993)) 38#1 13-24.

- LaFeber, The Clash: US-Japanese Relations Throughout History ch 10

- LaFeber, The Clash: US-Japanese Relations Throughout History ch 11

- Gavan McCormack, and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States (2012)

- T. R. H. Havens, Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975 (1987)

- LaFeber, The Clash: US-Japanese Relations Throughout History ch 12

- Tan Loong-Hoe; Chia Siow Yue (1989). Trade, Protectionism, and Industrial Adjustment in Consumer Electronics: Asian Responses to North America. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 4. ISBN 9789813035263.

- Carol Gluck; Stephen R. Graubard (1993). Showa: The Japan of Hirohito. Norton. p. 172. ISBN 9780393310641.

- Gluck; Graubard (1992). Showa: The Japan of Hirohito. pp. 172–73. ISBN 9780393310641.

- "Joint Statement on Japan-United States Energy Cooperation". Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum. 11 November 1983. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "AGREEMENT FOR COOPERATION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OP JAPAN AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONCERNING PEACEFUL USES OF NUCLEAR ENERGY" (PDF). Nuclear Material Control Center. Nuclear Material Control Center. 18 October 1988. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "United States-Japan Nuclear Co-operation Agreement" (PDF). Washington Policy & Analysis. Washington Policy & Analysis, Inc. 2 March 1988. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Christopher W. Hughes (June 2007). "Not quite the 'Great Britain of the Far East': Japan's security, the US-Japan alliance and the 'war on terror' in East Asia". Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP). University of Warwick. 20: 325–338. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Archived October 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Al Pessin (20 October 2009). "Gates: 'No Alternatives' to US-Japan Security Accord". GlobalSecurity.org. GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- John Pomfret (29 December 2009). "U.S. concerned about new Japanese premier Hatoyama". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Jane Perlez (10 July 2013). "China and Russia, in a Display of Unity, Hold Naval Exercises". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "Caroline Kennedy on Her Way to Becoming US Ambassador to Japan". Day News. 2013-09-20. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Weiner, Tim (1994-10-09). "C.I.A. Spent Millions to Support Japanese Right in 50's and 60's". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964-1968, Vol. XXIX, Part 2, Japan". United States Department of State. 2006-07-18. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Johnson, Chalmers (1995). "The 1955 System and the American Connection: A Bibliographic Introduction". JPRI Working Paper No. 11.

- "OEC: Japan". OEC. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Packard, George R. The Coming US-Japan Crisis. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 16-09-2011.

- Mann, Jim. FSX Deal Becomes Test of U.S., Japan Relations. 06 March 1989. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16-09-2011.

- Roger Buckley, U. S.-Japan Alliance Diplomacy, 1945-1990 (1995) p 144

- Dick K. Nanto, ed. Japan's 2011 Earthquake and Tsunami: Economic Effects and Implications for the United States (DIANE Publishing, 2011).

- Anthony Difilippo, The Challenges of the U.S.-Japan Military Arrangement (2002)

- "Advanced US drones deployed in Japan to keep watch on China, North Korea". The Japan News.Net. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-10-14. Retrieved 2018-10-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Yukinori Komine, "Okinawa Confidential, 1969: Exploring the Linkage between the Nuclear Issue and the Base Issue," Diplomatic History (2013) 37#4 pp 807-840.

- Hiroko Tabuchi and Thom Shanker, "Deal to Move Okinawa Base Wins Approval," New York Times Dec. 27, 2013

- Yoshihiro Makinioa (19 July 2013). "Japan dropped plan for eavesdropping network, still relies on U.S." The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "Country Ratings". Gallup.com. Gallup, Inc. 2007-02-21. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Americans, Japanese: Mutual Respect 70 Years After the End of WWII". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. Pew. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Global Indicators Database". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Saho Matusumoto, "Diplomatic History" in Kelly Boyd, ed., The Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing (1999) pp 314–165

- T.G. Fraser and Peter Lowe, eds. Conflict and Amity in East Asia: Essays in Honour of Ian Nish (1992) excerpt pp 77-91.

- Natsuki Aruga, Viewing American History from Japan" in Nicolas Barreyre; et al. (2014). Historians Across Borders: Writing American History in a Global Age. U of California Press. pp. 189–97. ISBN 9780520279292.

Further reading

| Library resources about Japan–United States relations |

Surveys

- Cullen, L. M. A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds (2003) online

- Dennett, Tyler. Americans in Eastern Asia: A Critical Study of the Policy of the United States with Reference to China, Japan, and Korea in the 19th Century (1922) 725 pages Online free

- Dulles, Foster Rhea. Yankees and Samurai: America’s Role in the Emergence of Modern Japan, 1791-1900 (1965)

- Emmerson, John K. and Harrison M. Holland, eds. The eagle and the rising sun : America and Japan in the twentieth century (1987) Online free to borrow

- Foster, John. American diplomacy in the Orient (1903) Online free 525 pp

- Green, Michael J. By more than providence: Grand strategy and American power in the Asia Pacific since 1783 (Columbia UP, 2017). online; 725pp; comprehensive scholarly survey.

- Iokibe Makoto and Tosh Minohara (Eng. translation), eds. The History of US-Japan Relations: From Perry to the Present (2017)

- Jentleson, Bruce W. and Thomas G. Paterson, eds. Encyclopedia of U.S. Foreign Relations ( 4 vol 1997) 2: 446–458, brief overview.

- Kosaka Masataka. The Remarkable History of Japan-US Relations (2019)

- Lafeber, Walter. The Clash: A History of U.S.-Japan Relations (1997), the major scholarly survey

- Mauch, Peter, and Yoneyuki Sugita. Historical Dictionary of United States-Japan Relations (2007) Excerpt and text search

- Morley, James William, ed. Japan's foreign policy, 1868-1941: a research guide (Columbia UP, 1974), toward the United States, pp 407–62

- Neumann, William L. America encounters Japan; from Perry to MacArthur (1961) online free to borrow

- Nimmo, William F. Stars and Stripes across the Pacific: The United States, Japan, and Asia/Pacific Region, 1895-1945 (2001) online

- Nish, I. Japanese foreign policy 1869–1942 (London, 1977)

- Reischauer, Edwin O. The United States and Japan (1957)

- Schaller, Michael. Altered States: The United States and Japan since the Occupation (1997) excerpt

- Treat, Paxson .Japan and the United States, 1853-1921 (1921) Online free

Specialized topics

- Asada, Sadao. From Mahan to Pearl Harbor: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States (Naval Institute Press, 2013)

- Austin, Ian Patrick. Ulysses S. Grant and Meiji Japan, 1869-1885: Diplomacy, Strategic Thought and the Economic Context of US-Japan Relations (Routledge, 2019).

- Barnhart, Michael A. Japan prepares for total war: The search for economic security, 1919–1941 (1987)

- Barnhart, Michael A. "Japan's economic security and the origins of the Pacific war." Journal of Strategic Studies (1981) 4#2 pp: 105–124.

- Berger, Thomas U., Mike Mochizuki, and Jitsuo Tsuchiyama, eds. Japan in international politics: the foreign policies of an adaptive state (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007)

- Borg, Dorothy, and Shumpei Okamoto, eds. Pearl Harbor as History: Japanese-American Relations, 1931-1941 (Columbia University Press, 1973), essays by scholars

- Bridoux, Jeff. American foreign policy and postwar reconstruction: Comparing Japan and Iraq (2010)

- Buell, Raymond Leslie. "The Development of the Anti-Japanese Agitation in the United States," Political Science Quarterly (1922) 37#4 pp 605–638, part 1 in JSTOR; and "The Development of Anti-Japanese Agitation in the United States II," Political Science Quarterly (1923) pp 38.1 57–81; part 2 in JSTOR

- Burns, Richard Dean, and Edward Moore Bennett, eds. Diplomats in crisis: United States-Chinese-Japanese relations, 1919-1941 (1974) short articles by scholars from all three countries. online free to borrow

- Calder, Kent E. "The Outlier Alliance: US-Japan Security Ties in Comparative Perspective," The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis (2003) 15#2 pp 31–56.

- Cha, Victor D. "Powerplay: Origins of the US alliance system in Asia." International Security (2010) 34#3 pp 158–196.

- Davidann, Jon. "A World of Crisis and Progress: The American YMCA in Japan, 1890-1930" (1998).

- Davidann, Jon. "Cultural Diplomacy in U.S.-Japanese Relations, 1919-1941 (2007).

- Dower, John. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999).

- Dower, John. War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986).