John Kendrick (American sea captain)

John Kendrick (1740–1794) was an American sea captain during the American Revolutionary War, and was involved in the exploration and maritime fur trading of the Pacific Northwest alongside his subordinate Robert Gray. He was the leader of the first US expedition to the Pacific Northwest. He is known for his role in the 1789 Nootka Crisis, having been present at Nootka Sound when the Spanish naval officer José Esteban Martínez seized several British ships belonging to a commercial enterprise owned by a partnership of companies under John Meares and Richard Cadman Etches. This incident nearly led to war between Britain and Spain and became the subject of lengthy investigations and diplomatic inquiries.

Kendrick was the first American to try to open trade with Japan. He began the Hawaiian sandalwood trade. He was killed by his enemy, Captain William Brown, during a ship cannon salute when one of cannons was loaded, purportedly by accident.

John Kendrick's reputation was tarnished by Meares and Etches, who claimed that Kendrick had persuaded and assisted Martínez to seize the British ships, in order to gain control of the maritime fur trade on the Northwest Coast for himself and the United States.[1] In addition, Robert Gray and his officer Robert Haswell, who had both been under Kendrick's command and resented him, publicly slandered and vilified him in various ways once they had returned to New England. Kendrick, who was killed in 1794 in Hawaii, was never able to return to New England and so was never able to defend his actions and reputation.[2]

Due to the slander of his detractors and his untimely death in Hawaii, Kendrick's legacy became obscured, his achievements overshadowed and forgotten, and accounts of his life often unfairly negative. Nonetheless, he was instrumental in pioneering trade in the Pacific Northwest, the Hawaiian Islands, and China, as well as helping the young United States establish itself as global trade power.[3]

Early life

Kendrick was born in 1740 in what was then part of the Town of Harwich, Massachusetts (now Orleans, Massachusetts), on Cape Cod. He was the third of seven children of Solomon Kendrick (or Kenwick) and Elizabeth Atkins.[4] His family name was originally spelled "Kenwrick", later "Kenwick" and "Kendrick".[5]

John Kendrick came from a long family line of seamen. Solomon Kenrick, his father, was master of a whaling vessel. John began going to sea with his father by the time he was 14 years old. By his late teens he was sailing with crews out of Potonumecut (today part of Orleans).[4] The Potonumecut area was home to remnant native tribes such as the Wampanoag. Kendrick's friendly relations with these natives later helped him forge friendships and alliances with native peoples in the Pacific Northwest, excepting the Haida chief Koyah.[6]

At the age of 20 he joined a whaling crew, working on a schooner owned by Captain Bangs. In 1762, near the end of the French and Indian War, John Kendrick served under his cousin Jabez Snow, on a militia mission in the frontier of Western New York.[4] Like most Cape Codders of the time, he served for only eight months and did not re-enlist.

During the 1760s John's father, Solomon, moved to Barrington, Nova Scotia. John stayed in Massachusetts, in Cape Cod and Boston, where an atmosphere of defiance and dissent was quickly growing during the early years of the American Revolution. There was widespread opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of the late 1760s. John may have been involved in the boycotts of British goods, riots over British impressment of American sailors, and other rebellious acts such as unrest around the Boston Custom House which led to the 1770 Boston Massacre.[4]

In late 1767 John Kendrick married Huldah Pease, who came from a seafaring family of Edgartown on Martha's Vineyard.[4]

American Revolution

Kendrick was reputed to have participated in the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773.[4] He was an ardent Patriot. During the American Revolutionary War he commanded the privateer Fanny (also known as the Boston), an eighteen-gun sloop of the Continental Navy with a crew of 104, which Kendrick converted into a brigantine. He was commissioned May 26, 1777.[7]

The Fanny disrupted British shipping and captured a few vessels, which won Kendrick a degree of fame and wealth.[4][8][9] In August, 1777, the Fanny and another privateer, General Mercer, captured two West Indiaman ships full of valuable cargo, the Hanover Planter and the Clarendon, after a battle with two 28-gun frigates. The captured ships were taken to Nantes in mid-August, 1777, causing an international stir. France had not yet joined the war and the prizes tested France's neutrality. The incident helped expedite France's decision to join the war against Britain.[4]

Kendrick returned home in the fall of 1778 a hero. With the prize money he had received from Louis XVI of France Kendrick bought a house, wharf, and store in Wareham, Massachusetts, and built the first public school there. He lived there with his family through the winter.[4]

In early 1779 he sailed to war again in command of the privateer Count d’Estang, which he owned in partnership with Isaac Sears. In April, southwest of the Azores, he was captured by the 28-gun British frigate Brutus and its 10-gun tender. The British captain impressed most of Kendrick's crew, eventually releasing Kendrick and the remaining 30 men in a boat. They travelled to the Azores and then Lisbon. In June, 1779, Kendrick and his remaining crew traveled to France, and then returned to America with the French fleet.[4]

Shortly after returning to America Kendrick sailed for the Caribbean in command of the Marianne, where he captured at least one more rich prize. He returned home once again shortly before the British surrender at Yorktown in October of 1781. By this time he had fathered six children during his sporadic visits home.[4]

When the war ended in 1783, Kendrick returned to whaling and coastal shipping until he became commander of the first American ships of discovery.

The Columbia Expedition

Not much is known about what happened to John Kendrick between the Revolution's end and his voyage to the Pacific Northwest. A syndicate led by Boston merchant Joseph Barrell financed the Columbia Expedition in 1787. The vessels included were the ship Columbia Rediviva and the sloop Lady Washington.

The command of the larger Columbia was given to Captain Kendrick, then 47 years old, and 32-year-old one-eyed Robert Gray was given Washington. Overall command of expedition was given to Kendrick.[10] The combined crews of the two ships numbered about 40 men, most hailing from Cape Cod, Boston, Rhode Island, and the North Shore of Massachusetts. Many were veterans of the Revolutionary War.[11]

The first officer of the Columbia was Simeon Woodruff, the oldest man on the voyage. Woodruff had sailed with James Cook aboard HMS Resolution on his famous third voyage around the world. As such, Woodruff had already been to the Pacific Northwest, Hawaii, and China.[12]

The second officer of Columbia was 25-year-old Joseph Ingraham, a veteran of the Massachusetts State Navy and POW during the Revolution.[13] Later, Ingraham became captain of the Hope, which sailed in 1790 to compete in the fur trade.[14] Unlike Gray and Haswell, Ingraham was an admirer and supporter of Kendrick. Ingraham kept a journal of the voyage, but it has been lost. He wrote a separate journal describing Nootka Sound in 1789, which has survived.[15]

The third officer of the Columbia was 19-year-old Robert Haswell, who kept an account of the voyage that came to serve as the main chronicle of the first two years. He also kept a journal during Gray's second voyage without Kendrick. Haswell came to dislike Kendrick and his journal is very critical of Kendrick's choices and abilities.[16]

The first officer of the Lady Washington was Robert Davis Collidge. Kendrick also brought two of his sons: Eighteen year old John Kendrick, Jr, as fifth officer of the Columbia, and sixteen year old Solomon Kendrick, as a common seaman.[17]

Outward voyage 1787–1788

The Columbia Expedition set sail from Boston Harbor on the morning of October 1, 1787, after a brief party with family and friends. The vessels reached the Cape Verde Islands on November 9, where Simeon Woodruff, after a dispute with Kendrick, left Columbia and went onto the islands with all his baggage. Kendrick was unhappy with the way Columbia handled, and felt that the hold had not been well packed, which Woodruff had been responsible for. When Kendrick ordered the hold broken up and repacked, Woodruff refused to help and after continued bickering Kendrick removed Woodruff from his position as first officer, after which Woodruff opted to leave the expedition entirely.[18] A Spanish captain passing by the islands offered to take Woodruff to Madeira. He eventually returned to America and lived in Connecticut most of the remainder of his life.

This incident deepened Haswell's dislike of Kendrick, as Haswell had been friendly with Woodruff and held him in high esteem. In his journal Haswell complained bitterly, describing Woodruff as "an officer under the Great Captain James Cook on his last Voyage". Haswell was mistaken: Woodruff was a gunner's mate under Cook, not an officer.[19]

While at Cape Verde Kendrick unpacked and reorganized the hold of the Columbia, hoping to improve its handling under sail. The hold of Columbia contained most of the expedition's provisions for the next two years, as well as a large assortment of trade goods hoped to be useful for acquiring sea otter pelts on the Pacific Northwest coast. These trade goods included such things as tin mirrors, beads, calico, mouth harps, hunting knives, files, and bar metal that could be worked into chisels or other tools. Despite the reorganization of the hold, Columbia continued to handle poorly.[20]

Kendrick continued the journey on December 21, 1787, and reached Brett Harbour on Saunders Island in the western Falkland Islands on February 16, 1788. Here they collected water and made final preparations for the voyage around Cape Horn.[20]

While sailing to the Falklands tensions between Kendrick and Haswell increased. One day Haswell struck a sailor named Otis Liscomb, who had failed to respond to Haswell's order to come on deck. When Kendrick saw Liscomb's bloody face he became angry and slapped Haswell and had him removed from his cabin to the common quarters. Haswell requested that Kendrick let him leave the expedition and Kendrick agreed, saying he could take the next vessel they encountered. But no other ship appeared. At the Falkland Islands Haswell was transferred from Columbia to Washington to serve under Gray. Haswell's dislike for Kendrick and Gray's ambition to be free from Kendrick's overall command reinforced one another. Their animosity grew over time and became a lasting problem for Kendrick.[21]

Kendrick considered wintering in the Atlantic, but decided to leave the Falklands on February 28, 1788. They sailed south toward Cape Horn. Five days later they passed Isla de los Estados (Staten Island), the eastern extremity of Tierra del Fuego. A storm was approaching from the west. Kendrick continued south, trying to skirt the edge of the storm. Other ships had escaped storms near Cape Horn by sailing farther south, a plan that Kendrick used. He evaded the worst of the storm by sailing to nearly 62° south latitude, about 400 miles (640 km) south of Cape Horn. Through March the ships struggled through cold and heavy weather, dealing with frost, sleet, twenty foot swells, high winds, and icebergs. About a month later William Bligh tried rounding Cape Horn in HMS Bounty but was forced back.[22]

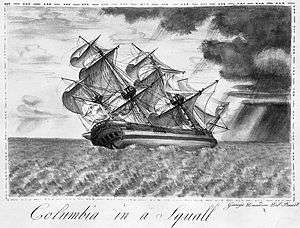

On March 22 the ships were about 670 miles (1,080 km) south-southwest of Cape Horn. They had passed west of the cape and so changed course toward the northwest. But during the night of April 1 the winds shifted, indicating dangerous weather. Kendrick had the Columbia adjust course in an attempt to race ahead. A signal gun was fired and the Washington followed. But in the morning light, with the storm still approaching, the two ships had lost sight of each other. Over three more days of heavy seas and blizzard-like conditions, they were entirely lost to one another. The Columbia, badly damaged, was driven back eastward, while the crew made what repairs they could.

For ten days Washington continued on through a series of violent squalls, culminating in a gale that Haswell described as "greatly sirpassing [sic] any thing before I had aney [sic] Idea of." Once the storm cleared Gray was pleased to be separated and saw a chance to free himself from Kendrick's command. Kendrick had written orders for Gray in the event they were separated. They would rendezvous at Alejandro Selkirk Island (then known as Más Afuera), the westernmost island of the Juan Fernández Islands, 540 miles (870 km) west of the coast of Chile. Gray made his way there, arriving on April 22, 1788. He brought the Washington to within a few miles of the island, then waited over night. In the morning Gray scanned the horizon and saw no sign of the Columbia, unsurprisingly since Washington was a faster vessel. Nevertheless, Gray figured he had fulfilled Kendrick's order and was now free to continue on alone.[23]

Gray was in need of water and wood, but there was no place to land at Alejandro Selkirk Island, so he headed north to Ambrose Island (Isla San Ambrosio), part of the Desventuradas Islands. Arriving on May 3, Gray sent men ashore. Spending the day on the island they did not find water but returned to the ship with a catch of fish, seals, and sea lions. Then Gray continued on, passing far west of the Galápagos Islands by May 24.[24]

Kendrick reached the rendezvous at Más Afuera about a month after Gray had left it. Kendrick had been instructed by Joseph Barrell "not to touch at any part of the Spanish dominions...unless driven there by some unavoidable accident". With Columbia badly in need of repairs and running out of water and wood, and Kendrick's eagerness for any news of Washington, he decided to risk visiting Más a Tierra, today known as Robinson Crusoe Island, where there was a small Spanish settlement.[25]

Kendrick had the Columbia approach the harbor, stopping about a mile offshore, unsure what sort of treatment he might receive. The Spanish governor of the island, Don Blas Gonzales, recognized a ship in distress. He sent out a fishing boat with a few armed men. The Spanish officer Nicholas Juanes came on board Columbia. He noted the ten cannons but thought the crew friendly and unthreatening. Kendrick said he needed a safe anchorage for making repairs and to take on water and wood. Juanes took first mate Joseph Ingraham back to shore to request permission to enter the harbor. Don Blas Gonzales was intrigued by this American ship, the first he had ever seen, and granted permission.[25]

The Columbia moored near the fort. Kendrick came ashore and met Gonzales, who found him affable and respectful. Inspecting the ship, Gonzales agreed with Juanes that the voyagers meant no harm. Although under Spanish law he was to seize foreign ships, mercy was permitted for ships in distress. Gonzales granted Kendrick six days for repairs and provisioning. The crew set to work repairing the damaged mast, sternpost, rudder, and many leaks. They filled water casks from a creek by the fort.[25]

After four days the Spanish packet boat Delores arrived with supplies and mail for the settlement. Kendrick wrote a letter to Joseph Barrell, informing him of their situation and separation from the Washington. He entrusted the letter to the captain of the packet boat.[25]

After the six days were up Kendrick prepared to leave, but heavy winds from the north forced Columbia to remain at anchor until June 3. Meanwhile the packet boat had reached Valparaíso, where news of Columbia resulted in orders to seize the ship. On June 12 a merchant brig, the San Pablo, was armed and sent to capture the Columbia. Shortly after the warship Santa Maria followed. By then Columbia was sailing north far off the coast and the Spanish ships did not find her. After a few days the San Pablo put into Lima with the news, prompting the Viceroy of Peru, Teodoro de Croix, to send another ship in pursuit of Columbia. After the pursuit ships returned without having found the Columbia Don Blas Gonzales was stripped of his office. Gonzales defended his actions in a court case that continued for years. Later, Kendrick enlisted Thomas Jefferson to try to help Gonzales.[25]

The Viceroy also sent warnings to the Viceroy of New Spain in Mexico City, which was forwarded to the Spanish naval bases at San Blas and Acapulco, and to the Spanish missions in California. The messages described the Columbia and Washington and details of their expedition, with orders that if either appeared they were to be seized and the crews arrested as pirates.[25]

The crews of both Columbia and Washington began to suffer from scurvy as they continued north.[26]

On August 2, 1788, the crew of Washington sighted land near the present border of California and Oregon, near the mouth of the Klamath River. After a friendly but brief encounter with a group of natives in a large redwood canoe, they continued north, looking for a safe harbor. They sailed past many native villages and encampments before finding a harbor deemed safe, in the vicinity of Tillamook Bay. They attracted the attention of many natives who began visiting the sloop for trade, offering, among other things, sea otter skins and fresh food, including baskets of berries, which helped relieve the symptoms of scurvy. Haswell noted that these natives had smallpox scars and carried steel knives, indicating previous encounters with trading vessels. On August 13, Gray anchored Washington in a protected inlet near a native village.[27]

The sloop remained in this harbor for five days. Many natives came to trade and parties were sent ashore to collect water and wood. After a couple days Gray decided to leave but Washington grounded on a rocky reef. While waiting for high tide one last party was sent ashore where an altercation occurred. In the ensuing chaos crewmember Marcus Lopius was killed. Officers Coolidge and Haswell, and another crewmember were wounded as they fled into the surf to their longboat. Native war canoes tried to capture the longboat and, failing that, positioned themselves between Washington and the open sea. During the night Washington was freed from the reef and tried to escape but grounded again, on a shoal. At high tide the next day, August 18, Washington was freed again. The sloop's swivel guns were used to hold off the war canoes and Washington escaped into the open ocean. Gray set a course for Nootka Sound, still far to the north.[28]

Shortly after this the Spanish war frigate Princesa, under José Esteban Martínez, and the packet San Carlos, under Gonzalo López de Haro, both sailing south from Alaska, passed but failed to spot Washington. Two weeks later they passed Columbia, again without visual contact. The next year Martínez and Haro would establish Santa Cruz de Nuca at Nootka Sound and, with Kendrick and Gray present, trigger events leading to the Nootka Crisis.[29]

Nootka Sound 1788–1789

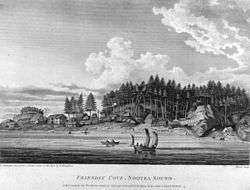

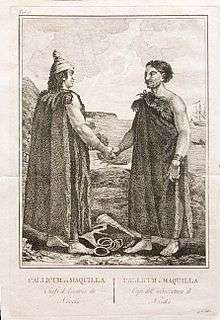

Washington arrived at Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound on September 16, 1788, finding another ship already there: Felice Adventurer, under John Meares, a British vessel but flying a Portuguese false flag to avoid paying for an East India Company licence, required of British merchants in China. Two more vessels arrived, Iphigenia Nubiana under William Douglas, who would later partner with Kendrick, and North West America under Robert Funter. The North West America was built at Nootka Sound and launched on September 20.[30][31] All three vessels were part of a fur trading venture under Meares. After a few days Meares left, and shortly after, on September 22, Kendrick's Columbia arrived. Kendrick re-assumed command of both ships and the expedition as a whole.[32] On October 26, 1788, the remaining two British ships left for Hawaii and China. Once they were gone Kendrick announced that the expedition would spend the winter in Nootka Sound. They would befriend the native Nuu-chah-nulth people and gain an advantage in the fur trade over the competing British ships.[33] During the winter Kendrick met and established friendly relations with the Nuu-chah-nulth chiefs Maquinna and Wickaninnish.[34] Kendrick knew Meares's ships would return after the winter. By staying at Nootka Sound he hoped to preempt the British by getting an early start.[30]

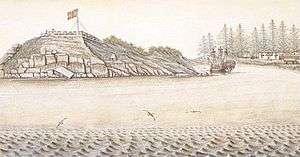

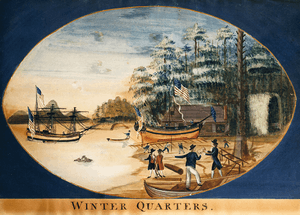

After the winter, Kendrick sent Washington under Gray out on a short trading voyage to the south. Departing on March 16, 1789, Gray visited Wickaninnish in Clayoquot Sound and cruised south looking for the Strait of Juan de Fuca. He collected many sea otter pelts in Clayoquot Sound and found the entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca before returning to Nootka Sound on April 22. Gray found the Iphigenia under William Douglas anchored at Friendly Cove, having arrived on April 19 after wintering in Hawaii. A few days later Funter's North West America arrived, also from Hawaii.[35] Kendrick had moved Columbia to a cove known as Mawina or Mowina, today called Marvinas Bay,[36] about 5 miles (8.0 km) deeper into Nootka Sound.[37] He had fortified a small island and built an outpost on it, with a house, gun battery, blacksmith forge, and outbuildings. Kendrick called it Fort Washington. It was the first US outpost on the Pacific coast. Kendrick intended it to be the foundation of an American presence on the Pacific Northwest coast, and as a headquarters for controlling the fur trade. Over the summer Kendrick used the outpost and his friendship with the Nuu-chah-nulth to collect hundreds of furs from the region.[38]

Kendrick had decided that Columbia was too unwieldy for close sailing on the Pacific Northwest coast. The smaller, more maneuverable Washington was better suited for trading. Therefore, almost immediately after arriving Washington was readied for another trading voyage. The British captains Douglas and Funter had discovered that Kendrick had control of the fur trade around Nootka Sound and that Gray had been trading in the south. Therefore the North West America set off northward to seek furs and Iphigenia prepared to do likewise. On May 2, days after North West America had left, Gray took Washington north as well.[39][40]

While sailing away from Nootka Sound Gray encountered Princesa, under Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez, who had come to take possession of Nootka Sound for Spain. Martínez informed the officers of the Washington that they were trespassing in Spanish waters and demanded to know their business. Gray and his officers showed him a passport and made weak excuses for being on the Northwest Coast. Martínez knew they were dissembling but let them go, knowing that the command ship Columbia was trapped in Nootka Sound.[41]

Martínez anchored in Friendly Cove, Nootka Sound, on May 5, 1789. Within the day Douglas and Francisco José Viana, the nominal captain of the Iphigenia, were meeting with Martínez on Princesa. Kendrick soon arrived and joined them. When questioned about his presence at Nootka Sound Kendrick dissembled, saying Columbia had been badly damaged and the crew suffering from scurvy. They had put into Nootka for repairs and recovery. Kendrick told Martínez that, expecting to have to winter at Nootka, he had built a house for the crew, a blacksmith forge, and a gun emplacement for protection. He said he had sent Washington north to look for material for barrel hoops. Kendrick readily acknowledged Spanish authority in the region and said he would leave as soon as Columbia was repaired.[42] Douglas gave similar excuses for Iphigenia and gave over the ship's papers which, being in Portuguese, Martínez held for translation.[43]

Kendrick saw the arrival of Martínez as potentially beneficial for his own goals, and he treated Martínez with deference and courtesy. He offered Martínez the use of his blacksmith, provided sail canvas, deck fixtures, and introduced him to the local Nuu-chah-nulth, seeking to promote friendship. Douglas later claimed that Kendrick and Martínez made an alliance against him and the British in general. Later still, John Meares accused Kendrick of convincing Martínez to seize British ships, though Kendrick denied it. It is not clear whether Kendrick agreed with Martínez's plan for seize Iphigenia, but Martínez did tell Kendrick he planned to arrest Meares when his command ship arrived, and gained Kendrick's complicity in that regard. Whatever the case, Kendrick had a motive for encouraging Spanish–British conflict, whether tacitly or directly, since it would reduce British competition in the fur trade and give him more time to establish an American outpost.[44]

On May 12, 1789, the Spanish vessel San Carlos arrived. With this reinforcement in place, Martínez seized Iphigenia and arrested the crew. This alarmed Chief Maquinna, who moved his Nuu-chah-nulth people from Friendly Cove to a village deeper into Nootka Sound.[45] After a couple weeks Martínez, in a tricky diplomatic situation, decided to let Iphigenia go after Douglas agreed to certain conditions. Kendrick and Ingraham acted at witnesses to the agreements. Among the conditions Martínez required Douglas to promise to leave the Pacific Northwest and never return—a promise he broke immediately upon leaving Nootka Sound as he sailed north to cruise the coast for furs.[46] Douglas sailed from Nootka Sound around the start of June. On June 8, 1789, the North West America returned. Martínez confiscated the vessel as security for payments Douglas owed for repairs and supplies given to Iphigenia.[47]

On June 15, 1789, Meares's small sloop Princess Royal, under Thomas Hudson, arrived at Friendly Cove. Needing repairs and in no condition to resist, Hudson readily accepted Martínez's authority.[48] Robert Gray returned to Nootka Sound on June 17, finding the Spanish in control, Fort San Miguel built, North West America captured and Princess Royal detained. Gray sailed Lady Washington directly to Kendrick's outpost at Marvinas Bay. While Gray had been away Kendrick's friendship with the natives had resulted in his collecting of hundreds of furs. Thinking they would soon depart, Kendrick took Columbia and Washington to Friendly Cove, anchoring there on June 28. On July 2, Martínez let the Princess Royal depart. Within hours Meares's command ship Argonaut under James Colnett arrived.[49]

Martínez and Colnett clashed right away, each claiming Nootka Sound by authority of their respective kings. Despite his misgivings, Colnett allowed Argonaut to be brought into Friendly Cove and tied to Princesa and Columbia. As tensions rose while Martínez and Colnett continued to argue, Kendrick, knowing that Martínez was planning to seize Argonaut, prepared for the possibility of violence. The next day the arguments between Martínez and Colnett nearly turned violent, and Martínez had Colnett arrested. Martínez had Princesa's cannon loaded and ready, and asked Kendrick to do the same with Columbia, which he did. Seeing Argonaut trapped between the two ships as well as the cannon of Fort San Miguel, Colnett realized that resistance was futile.[50]

The events set in motion during the summer of 1789, especially the seizure of Argonaut, lead to the Nootka Crisis. It took time for the news to reach Europe, but when it did it nearly resulted in war between Britain and Spain.

Northwest coast 1789

On July 13, 1789, the day after Martínez seized Princess Royal, the Nuu-chah-nulth leader, Callicum, the son of Maquinna, went to Friendly Cove. He called angrily to Martínez, who shot him dead with a musket. Sources differ over the details of the event, [51][52] but whatever the case it deepened the rift between the Spanish and Nuu-chah-nulth. Maquinna fled to Clayoquot Sound.[53] The next day Kendrick decided it was time to leave Nootka Sound.[54]

Kendrick asked Martínez if he would be allowed to return to Nootka Sound the next year. Martínez agreed, with certain conditions and requests, to which Kendrick agreed. Martínez asked Kendrick to take the prisoners from North West America to Macau, offering 96 sea otter skins to cover expenses. He also asked Kendrick to sell 137 prime sea otter skins in Macau for him. Martínez also offered to deliver letters from the Americans. Kendrick wrote to Joseph Barrell, but knowing the letter would probably be read by the Spanish, kept his message short. He said he would cruise north then proceed to China, where he expected to receive instructions from Barrell. He also wrote a letter to his wife Huldah.[54]

Kendrick's son, John Kendrick Jr, announced that he had decided to stay at Nootka Sound and join the Spanish Navy. An account by a Spanish officer described the elder Kendrick standing in tears as he gave advice and said goodbye to his son.[54]

On July 15 Columbia and Washington, under Kendrick and Gray, left Nootka Sound. Instead of cruising north they sailed south to Clayoquot Sound, where they stayed for two weeks. The ships anchored near Opitsaht, the largest native village in the area and home to Chief Wickaninnish. Kendrick and his men knew many of the natives at Opitsaht, some of whom had recently come from Nootka Sound. Trading began immediately and continued during their time there.[55]

While at Clayoquot Sound, Kendrick and Gray switched vessels. Kendrick ordered Gray to take Columbia to China, and Kendrick would take Washington north, trading for furs. Kendrick recognized that with the British driven off out of the trade due to the Nootka Crisis the Americans had a window of opportunity on the Northwest Coast. All the furs in Washington were transferred to Columbia and the crews were divided so Kendrick would have a full complement of experienced sailors on Washington. On July 30 Gray sailed Columbia out of Clayoquot Sound, making for Hawaii and China.[56]

The reason for this exchange of ships remains unknown, but one reason could be that Kendrick thought Washington was easier to handle because she was smaller. Whatever the reason, Gray returned to Boston via Canton, later taking a second expedition in Columbia that would enter the Columbia River on the modern Washington-Oregon border, and result in its naming for the ship.

Kendrick's movements after leaving Clayoquot Sound are unknown. The next confirmed report dates to September, about a month after leaving Clayoquot. Kendrick encountered Thomas Metcalfe's Fair American near Dundas Island and Dixon Entrance. Metcalfe continued to Nootka Sound and told Martínez about meeting Kendrick. Martínez wrote that Kendrick was in "one of the mouths of the Strait of Fonte". How Kendrick got from Clayoquot to Dixon Entrance is not known. There is some evidence that he might have entered the Salish Sea, passing east of Vancouver Island.[57]

After his meeting with Metcalfe, Kendrick sailed across Hecate Strait to Haida Gwaii. His activities there are not known in detail but he likely stopped at several Haida villages such as Skidegate and Skedans. At Anthony Island, or SG̱ang Gwaay, he traded with the Haida village of Ninstints, under Chief Koyah, or Coyah.[58]

Ninstints had been visited by George Dixon in 1787, and by Robert Gray in June, 1789, when Kendrick sent him north to trade. Robert Haswell's account of Ninstints during Gray's visit is the earliest written description.[59] Kendrick arrived at Ninstints about three months after Gray's visit.

While Kendrick trading at Ninstints minor thefts from the ship caused some tension. One day Kendrick's clothes, which had been hung out to dry, were stolen. Kendrick had Chief Koyah and Chief Skulkinanse held as hostages until the stolen goods were returned. The clothes and most other missing items were returned. Knowing that trading would be over once the chiefs were released Kendrick demanded all the remaining furs be brought for trade. Some accounts say Kendrick paid for these furs at the same rate he had been paying,[58] others say he forced the Haida to accept a lower rate.[59] After this the chiefs were released and Kendrick left. The incident caused Koyah to lose his chieftainship, although later traders still had to work with him and he seemed to retain an important role in Ninstints.[58]

Robert Gray returned to Ninstints in 1792 and Robert Haswell wrote what he claimed was the Haida account of the incident. He said that Kendrick had tied a rope around Koyah's neck, whipped him, cut off his hair and painted his face, among other things.[59] But both Gray and Haswell had been slandering Kendrick for years by this point and their accounts cannot be fully trusted.[58]

Two years later, when Kendrick returned, the Haida had not forgotten this treatment and a battle ensued. The natives captured the arms chest of Washington. Kendrick and his crew had to retreat below decks. He and his officers fought off the attack. Kendrick, seeking revenge, killed a native woman who had encouraged the attack in the water after her arm had been severed by a cutlass and killed many other natives with cannon and small arms fire as they retreated.[60]:63

Hawaii 1789

Kendrick went to the Hawaiian Islands, arriving in November, 1789. Lady Washington was the 15th Western ship known to have visited Hawaii after James Cook.[61] Kendrick sailed around the Island of Hawaii and anchored in Kealakekua Bay, not far from where Cook had been killed in 1779. Native Hawaiians came aboard to trade. Kendrick asked for Chief Kaʻiana, who had been on the Iphigenia at Nootka Sound and was friendly to Kendrick and other traders. Kaʻiana brought Kendrick a letter from Richard Howe, the clerk of Columbia, which had been in Hawaii in August. The letter warned of native duplicity and told of an attack on Iphigenia that summer. Kendrick also learned of the complicated and changing political situation in Hawaii. Chief Kamehameha I and his sub-chiefs, such as Kaʻiana were expanding their power and eager to acquire firearms, which they had been obtaining from other traders. Kendrick was reluctant to trade firearms, fearing his own safety, but probably provided a few in trade for provisions.[62]

During his stay at Kealakekua Bay Kendrick recognized sandalwood. Knowing that sandalwood was prized in China he asked Kamehameha for permission to leave a man to harvest sandalwood for later pickup. Kamehameha wanted assistance training his men in the use of firearms. The details of the deal are not known, but whatever the exact terms Kamehameha agreed and Kendrick left his carpenter Isaac Ridler and two others, James Mackay and Samuel Thomas.[62]

After leaving Kealakekua Bay Kendrick sailed through the island chain. He stopped at Kauai and Niihau to top off his provisions with water, yams, and hogs. Then he made for Macau, China.[62]

Shortly after Kendrick's visit to Hawaii, another trader, Simon Metcalfe killed about a hundred Hawaiians in an event called the Olowalu Massacre. About the same time the small ship Fair American, captained by Simon Metcalfe's son Thomas Metcalfe, was attacked and captured. The Fair American and the one survivor, Isaac Davis, came under the control of Kamehameha. Kendrick's three men, along with Isaac Davis and a man left by Simon Metcalfe, John Young, all found their lives at risk and survived by serving under Kamehameha, teaching Hawaiians not only how to use muskets but also how to sail the Fair American and use its cannons. These things helped Kamehameha invade Maui and begin his conquest of all the Hawaiian Islands.[63]

Macau 1790–1791

Kendrick anchored about a mile offshore of Macau on January 26, 1790. Gray had arrived in November and by January had made it to Whampoa, a trading center near Guangzhou (Canton), about 30 miles (48 km) up the Pearl River. Both captains found trading difficult under the Canton System. Kendrick sent a letter to Gray, telling of his arrival and asking for advice on how to proceed. Gray sent a letter back along with letters from Joseph Barrell, the owner of their venture. Gray described his difficulties with the Canton System and suggested Kendrick go to a smuggling area called Dirty Butter Bay on the west side of Montanha Island (today part of Hengqin). Gray also provided the names of buyers who would assist in smuggling. The letters from Barrell were friendly and reaffirmed Kendrick's command of the venture and broad authority to continue as he judged best.[64]

Kendrick took Lady Washington to Dirty Butter Bay on January 30, 1790. He found it rife with smuggling and illegal activity. There were two East India Company hulks acting as floating warehouses full of opium. Kendrick received another letter from Gray, who suggested Kendrick sell his cargo to Gray's agent in Whampoa, and that Gray would take the money himself. Kendrick refused, saying he might bring Washington up to Whampoa. To this Gray replied, warning of the difficulties involved and suggesting Kendrick remain where he was.[64]

Kendrick wrote back with various questions. He asserted his command of the joint venture by asking for a full account of the cargo sold and remaining on Columbia, the amount and quality of Chinese goods acquired, and other details. Gray refused to provide Kendrick with this information. Gray wrote to Barrell that he had brought 700 skins to China although it was later determined that he had sold 1,215 skins and tampered with the inventory records from Clayoquot Sound. Whatever the case, Gray's cargo was sold for $21,400, a fairly low price per skin. About half of this money was spent on the costs of his long stay at Whampoa, leaving $11,241. With that he bought 221 chests of cheap tea. About half of the tea was spoiled by the time Gray returned to Boston and Barrell took a financial loss for Gray's first voyage.[64]

Before Gray left China Kendrick sent him a number of artifacts he had collected on the Pacific Northwest Coast, to be brought back to New England for a new museum (today the Peabody Essex Museum). Kendrick, having not received an accounting of Gray's business in Whampoa, sent a copy of his letter asking for such, but again Gray ignored it. On February 9, 1790, Gray left Whampoa. While waiting for a storm to pass Gray anchored Columbia less than 10 miles (16 km) from Lady Washington, but avoided all contact and communication. On February 12, he left for Boston.[64]

Kendrick fell ill with a long fever, and fell into debt. But by spring his prospects improved. The fever abated. He sold Martínez's furs for $8,000 and his own for $18,000, a far better price per fur than Gray had managed. Now flush with cash he paid his debts and rented a house in Macau while making various preparations for a return voyage to the Pacific Northwest. He had Lady Washington refitting as a brigantine similar to the privateer Fanny he had captained during the Revolutionary War. A second mast was added to Washington, along with new sails and rigging.[65]

As spring progressed Kendrick found himself stuck in Macau. The Chinese refused to give him permission to leave port and the Portuguese Governor of Macau, Lazaro da Silva Ferreira, would not intervene. The reason for this is unclear. Stuck in Macau, Kendrick asked William Douglas for assistance. Douglas had been captain of Iphigenia but had left Meares's company and taken command of the American schooner Grace, sailing under a US flag. Kendrick's first mate, Davis Coolidge, became Douglas's first mate. Kendrick and Douglas formed a loose partnership. Douglas was about to sail to the Pacific Northwest. He agreed to stop in Hawaii on the way back and pick up Kendrick's sandalwood.[65]

Around this time John Meares arrived in London, where he began to fan the flames of the Nootka Crisis, which was rapidly heading toward war between Britain and Spain. Part of Meares's claims, made to Parliament and Prime Minister William Pitt, was that Kendrick was the true architect behind the Spanish seizure of British ships at Nootka Sound. News of impending war between Britain and Spain reached Macau in the summer of 1790. Kendrick was arrested by soldiers in Macau and ordered to leave. He retreated to Washington in Dirty Butter Bay.[66]

On August 9, 1790, Gray returned to Boston with Columbia. There were large celebrations of this first US circumnavigation and Gray became a national hero. However, the venture was a failure financially. Gray and Haswell blamed Kendrick for the failure, describing him as careless, self-interested, and seeking to cheat Barrell and the other owners. Gray and Haswell claimed they themselves had saved the venture from the total loss that would have occurred under Kendrick's command. They pointed to Haswell's journal, which had been rewritten on the return voyage, as evidence for a long list of grievances against Kendrick. Their claims were half-truths at best, outright lies at worst. They also tried to discredit Joseph Ingraham, the one officer of Columbia who supported Kendrick. Ingraham was unable to defend himself or Kendrick, since he had accepted command of a new trading venture owned by Barrell's competitor, Thomas Handasyd Perkins, and had almost immediately left Boston for the Pacific Northwest. Some were skeptical of Gray's claims about Kendrick, such as the clerk John Hoskins and Joseph Barrell himself. In addition, questions were raised about the total number of furs Gray sold in China. Gray said they sold 700 skins, with Haswell's records as evidence. Barrell's agent at Canton said there were at least 1,215 furs, and perhaps more than 1,500. The discrepancy was never resolved.[67]

Gray proposed another venture in which he would have command of Columbia, with Haswell as first mate, and without Kendrick's overall command. The owners were unsure and several declined, but others invested, including Robert Gray himself. Barrell, reluctant and not fully trusting Gray, paid for the last five-fourteenths share. While Columbia was being made ready Gray, now a hero, continued to disparage Kendrick and news of Kendrick's "nefarious character" spread through New England and the United States. Newspapers published articles condemning Kendrick and calling him a rogue and a cheat. He was also held responsible for the Nootka Crisis and the looming war. John Quincy Adams wrote about Kendrick's "egregious knavery and unpardonable stupidity". Kendrick's reputation never recovered from these smears and slanders, even to the present day.[67]

Solomon Kendrick, who had returned with Gray, quickly joined another venture and left Boston for the Pacific Northwest on Jefferson, under captain Josiah Roberts. Joseph Ingraham did likewise, obtaining command of the sloop Hope and leaving Boston on September 17, 1790. The Columbia left Boston on October 2, 1790, with Gray as captain and Haswell as first mate. Joseph Barrell placed John Hoskins, one of Kendrick's supporters, on board as supercargo. Barrell, suspicious of Gray's claims and his handling of cargo in China, gave Hoskins broad authority in the management of cargo and instructed Gray to consult with him on all matters of trade. Hoskins' task would prove very difficult, as Gray and Haswell united against him during the voyage.[67]

On October 28, 1790, the First Nootka Convention was signed, averting a British–Spanish war. Under the agreement Spain was to pay damages for John Meares's seized ships and to return the land in Nootka Sound that Meares claimed to have purchased. George Vancouver was to sail to Nootka Sound to implement the agreement. His voyage, known as the Vancouver Expedition, along with the Butterworth Squadron—ostensibly a private merchant fleet but also supporting Vancouver and British interests—would later play a major role in John Kendrick's life as well as his death.[68]

During all this time Kendrick remained at Dirty Butter Bay, unable to leave due to the restrictions that had been placed upon him. In late 1790 a new governor of Macau, Vasco Luis Caneiro de Sousa de Faro, was appointed, and Kendrick's restrictions were lifted. By this time Douglas had returned with a cargo of furs, Kendrick's Hawaiian sandalwood, and Kendrick's men James Mackay and Samuel Thomas. After selling the furs and sandalwood the two captains decided to sail together to Japan in an attempt to open trade there. They left China on March 31, 1791.[68]

Japan

Kendrick left Macau in March, 1791, along with William Douglas, formerly captain of the Iphigenia but now of an American ship called Grace. They decided to attempt to open trade with Japan, which was closed to almost all foreign trade under the sakoku policy.[69] Kendrick and Douglas approached the Kii Peninsula of Japan on May 6. Seeking shelter from an approaching typhoon Kendrick and Douglas sailed into the channel between the mainland and the island of Kii Ōshima, near the fishing villages of Kushimoto and Koza. Both villages immediately sent messages to the daimyō at Wakayama Castle. After the storm passed a few Japanese fishermen visited the ships. Kendrick offered food and drink, and a few of the fishermen went on board. None of the ships crewmembers spoke Japanese, but the Chinese crewmen were able to communicate via writing. Kendrick and Douglas learned that there was no market for sea otter furs in Japan, contrary to the rumors they had heard in Macau. The fishermen also persuaded Kendrick and Douglas not to go to Osaka, where they would have faced certain arrest.[70]

While they waited for favorable weather five men were sent ashore on Oshima Island to collect water and wood. They fired a warning musket shot at a local farmer who tried to stop them. In the meantime the messages from the villages reached Wakayama Castle and the daimyō sent a force of samurai. On May 17, Kendrick and Douglas departed, perhaps having heard that troops were coming. The samurai arrived two days later.[71]

The result of this first visit of Americans to Japan was largely symbolic for the United States. For Japan it resulted in a new system of alarms and coastal patrols, increasing Japan's isolation under sakoku.[72][73][74]

A few days after leaving the Kii Peninsula Kendrick and Douglas came across some islands not on any charts they had. Possibly part of the Nanpō Islands, they named them the "Water Islands". Here they decided to separate. Douglas sailed to Alaska, perhaps by way of Hawaii, while Kendrick made for the Pacific Northwest coast.[75]

Northwest Coast 1791

In early June, 1791, Kendrick arrived at Bucareli Bay. He spent about a week trading in Tsimshian and Haida territory. He visited several villages in Haida Gwaii before arriving at the southern end of the islands.[76]

On June 13 he visited the Haida village X̱yuu Daw Llnagaay, also spelled Ce-uda’o Inagai. The village is located on a point north-east of Saawdaan G̱awG̱a, or Keeweenah Bay, near Ninstints in the territory of Koyah, with whom Kendrick had had trouble in 1789. Sources differ over exactly how events unfolded. Sources that depend on Gray and Haswell's accounts are problematic due to their desire to smear Kendrick. Whatever the details, trading proceeded in a friendly manner for a couple of days and many Haida from the region came. A festive mood developed and Kendrick relaxed his security. Kendrick was told that Koyah was no longer a chief, and when Koyah came he appeared to hold no ill feelings.[76]

Kendrick allowed about 50 Haida, men and women, aboard his ship.[77] Koyah joined the Haida trading on board, having brought his own furs to trade. By some accounts Kendrick traded a blue nankeen coat to Koyah.[76]

During the trading on board one of the Haida chiefs, perhaps Koyah according to some versions of the story, went to the quarterdeck and gained control of one of the weapon chests. At this point Haida warriors, in what seems to have been an unplanned attack, drew knives and menaced the crew, who retreated to the middle deck and then below deck. The Haida gained control of the ship's deck.[77][76] Haida canoes had crowded alongside Washington and more warriors boarded. According to some accounts Koyah began taunting Kendrick, now alone on the quarterdeck. There was little Kendrick could do. He tried to bargain with Koyah, offering to pay the Haida to leave the ship, to no avail. While the men below were arming themselves with weapon stores in the hold, and preparing to blow up the ship if necessary, Kendrick and Koyah fought near the companionway. Koyah wounded Kendrick with his knife twice in the abdomen. Crewmembers began to fire at the Haida warriors. Kendrick retrieved a pistol from his cabin and led the crew back on deck. A hand-to-hand battle ensued. About 15 Haida, men and women, were killed in the struggle.[76] One Haida woman had climbed up the chains supporting the mainmast and had been shouting encouragement to the Haida, urging them to fight. Although badly wounded she remained aloft until all the other Haida had fled the ship, at which point she jumped into the sea and attempted to swim despite having lost an arm in the battle. She was shot as she struggled in the water. The crew fired upon the retreating Haida with muskets and cannon, and pursued them in boats. Many Haida died in the battle. Koyah was shot but survived. His wife and child were killed according to some accounts.[76]

The battle became a famous and oft-told story, and accounts portrayed Kendrick in differing ways. One second-hand account claimed that Kendrick had been drinking. Others blamed for letting the Haida gain control of the ship as well as allowing the brutal retaliation following the regaining of control. Still others found the slaughter hard to believe and supported Kendrick's actions.[76]

Having been treated as 'ahliko', or a lower class person, Koyah had lost face according to Haida law. His family and allies went on to capture two vessels to restore the honour of his matrilineage according to Haida law.[77]

Kendrick left immediately and went to Bucareli Bay where he and his crew spent a few weeks recuperating before sailing to Nootka Sound.[76] He did not know what the current situation would be at Nootka Sound. He had not yet that the Nootka Convention had been signed in late 1790, preventing war. For all he knew a global war might have begun. Therefore Kendrick entered Nootka Sound in a dramatic fashion, with cannons loaded and matches lit, and the crew all armed and ready to fire.[78] The Spanish officer Francisco de Eliza had re-established the fort at Friendly Cove but was away exploring the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Strait of Georgia. The acting commandant, Ramón Saavedra, sent an armed boat, telling Kendrick that Nootka Sound belonged to Spain and no one could enter or trade without permission. Kendrick defiantly said they had come to trade and would do so. Saavedra decided to take no action and await the return of Eliza. Kendrick arrived at his old base in Marvinas Bay, Nootka Sound, on July 12. [76]

At Marvinas Bay Kendrick was welcomed by the native Nuu-chah-nulth. The friendship he had forged with them had lasted and was even strengthened by their continued frustration with the Spanish. Kendrick began to negotiate alliances with chiefs Maquinna, Claquakinnah, Wickaninish, and others. From Saavedra he learned of the Nootka Convention and that British traders would be allowed back to Nootka Sound and permitted to trade along the coast. Kendrick hoped that a strong alliance with the natives could help him out-compete the British traders who would soon be returning.[79]

Many chiefs gathered at Marvinas Bay. Kendrick entertained them with Chinese fireworks. He warned them that both the Spanish and British were coming in larger numbers with the intention of taking over the land. Kendrick told them that if he held deeds to their land it could prevent Spanish and British conquest. He promised that they would retain all the rights and that he was essentially asking for the right to use the region as one of the Nuu-chah-nulth. Additionally he would be bound to defend the lands against Europeans and other tribes outside their confederation. But the most important thing he offered, from the Nuu-chah-nulth perspective, was firearms. If they were well-armed they could defend themselves against traders who previously had felt free to raid villages and shoot natives. The memory of Maquinna's brother Callicum being shot to death by the Spanish was still fresh.[80]

The chiefs agreed to Kendrick's proposal. In July 1791 Kendrick purchased Marvinas Bay from Maquinna and other chiefs, with "all the land, rivers, creeks, harbours, islands, etc., with all the produce of sea and land appertaining thereto."[81][80] Kendrick then went to Tahsis, deeper into Nootka Sound, and made a similar agreement. Then he maneuvered Washington through the narrows north of Nootka Island into Esperanza Inlet, thereby avoiding the Spanish fort at Friendly Cove. In Esperanza Inlet and Nuchatlitz Inlet he made two more land purchases of the same sort.[80]

In early August 1791, Kendrick sailed south to Clayoquot Sound. Chief Wickaninnish, having heard of Kendrick's activities, was waiting for him, prepared to make a similar deal of land for firearms. On August 11, 1791, Wickaninnish and other chiefs granted Kendrick essentially all the land around Clayoquot Sound. [82] The deed mentions only four muskets traded in exchange, although by 1792 Wickaninnish was said to have acquired about 200 muskets from Kendrick.[83] Kendrick's land purchases collectively gave him title to over 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) of Vancouver Island, including nearly all of Nootka Island and the lands around Nootka Sound and Clayoquot Sound.[80] Following these purchases, Kendrick built a new Fort Washington on an island in Clayoquot Sound.[83]

On August 29, 1791, the Columbia arrived at Clayoquot Sound, having returned to the Pacific Northwest on a second voyage. Robert Gray was captain and no longer under Kendrick's command. Robert Haswell was first mate. The supercargo was John Hoskins, sent by Joseph Barrell to oversee the business and finances of the venture. Hoskins, unlike Gray and Haswell, thought highly of Kendrick. Barrell had sent him in part to learn the truth about Kendrick in light of Gray and Haswell's denouncements. Upon meeting in August Kendrick did not yet know how badly Gray and Haswell had damaged his reputation. Gray and Haswell acted politely toward Kendrick, although Haswell wrote scathing condemnations in his journal.[83]

From Hoskins Kendrick learned of other traders on the coast—at least three American and five British ships. These vessels were mostly trading in the north, having found few furs on Vancouver Island: Kendrick had already acquired most of them and had negotiated advance payments for future furs. Joseph Ingraham later wrote that the natives around Nootka Sound always asked about Kendrick, saying they had many furs for him and would not sell to anyone else.[83]

The day after arriving some of the officers of Columbia visited Kendrick's Fort Washington, which Hoskins described as a rough log outpost with living quarters and a warehouse, with a US flag flying. Lady Washington had been hauled on shore and was being graved in preparation for sailing to Hawaii and China. Kendrick was given a letter from Joseph Barrell, from which he learned that Columbia was no longer under his command. In a reply letter Kendrick pointed out how unfortunate this was, since he could have added over 1,000 sea otter skins to the 500–600 Gray had gathered. Seeking some way to make this work, Kendrick offered Hoskins 1,000 furs in exchange for payment for his men and his Macau debts, which were about $4,000. Hoskins, fearing that such a deal would be used by Gray to Kendrick's disadvantage, said he did not have the authority. Thus, lacking further instructions from Barrell, Kendrick found himself on his own with Washington. He decided to continue on as he had been. Matters with Barrell could be resolved later.[83]

Borrowing Kendrick's strategy from the first voyage, Gray planned to winter in Clayoquot Sound so as to get an early start the next year. Kendrick helped tow Columbia to a cove for the winter. After Kendrick left Gray had his men build an outpost he named Fort Defiance. On September 29, 1791, Kendrick sailed for Hawaii. Over the winter Gray proved unable to maintain the friendship with Wickaninnish's people that Kendrick had built. In an incident over a coat Gray took Wickaninnish's brother hostage, threatening to kill him. Later, Gray's Hawaiian servant deserted and went into hiding among the natives. In retaliation Gray took another hostage.[83]

Toward the end of the winter Gray discovered what he thought was a conspiracy to attack his outpost and ship. In response Gray decided to destroy Opitsaht, the main native town of Clayoquot Sound and seat of Wickaninnish. As Columbia left Clayoquot Sound in March 1792, Gray ordered a cannonade upon Opitsaht, which was utterly destroyed. Although the town was empty at the time it contained over 200 ornately carved buildings. John Boit wrote of his sadness to see the town destroyed, noting that every door had been elegantly carved, often in the form of a totemic animal whose mouth functioned as the entry. Wickaninnish's people remained loyal to Kendrick, but their good feelings toward American traders over the British, which Kendrick had obtained, was largely ruined by Gray's actions.[83]

Hawaii and Macau 1791–1793

Kendrick arrived at Kealakekua Bay on the Island of Hawaii in late October, 1791. From Kaʻiana Kendrick learned that Kamehameha was now king of the entire island and that there was turmoil, danger, and ongoing war among most of the Hawaiian Islands. Kendrick left Kealakekua Bay after a few days and sailed to the island of Kauai, which was relatively safe at the western end of the main islands. By October 27, 1791, he was at Kauai. With the approval of Chief Inamoʻo, who was serving as regent while Chief Kaumualii was away, Kendrick left three men on the nearby island of Niiahu. John Williams, John Rowbottom, and James Coleman were to work on Niihau and Kauai, trading for pearls and preparing cargoes of sandalwood.[84]

Kendrick arrived at Macau on December 7, 1791, and was soon again anchored at the smugglers haven Dirty Butter Bay. Several other American traders were there, including Joseph Ingraham of the Hope, Crowell of the Hancock, and Coolidge of the Grace. The Fairy arrived soon after Kendrick. From these traders Kendrick learned the full story of Gray and Haswell's denunciation of him in Boston. On March 28, 1792, he wrote to Joseph Barrell, defending himself against the charges made against him and describing how Gray had cheated Barrell by under-reporting furs sold in Macau and selling the difference for his personal profit. He also described the land purchases he had made and promised to send copies of the deeds. Lacking specific instructions he proposed that he would continue in Barrell's employ "as usual", including, he suggested, command of Columbia. Alternatively, if Barrell was not interested in continuing the relationship, he proposed buying Lady Washington for $14,000, plus interest, and operating on his own. He entrusted the letter to Ebenezer Dorr, who had come to Macau with Ingraham on the Hope and was returning to Boston on the Fairy.[85]

Kendrick could not expect a reply from Barrell for at least a year. In the meantime he decided to strengthen his position in Hawaii and on the Northwest Coast. He felt he could not honorably return to Boston until his grand plans in the Pacific had matured and large profits made. Not longer after Dorr and most of the other traders left Kendrick fell ill. When Ingraham left on April 1, 1792, he described Kendrick as near death.[85]

In time Kendrick recovered and, over the summer of 1792, built a tender for Washington. Named Avenger, it was probably a sloop about 36 feet (11 m) long, with a crew of about ten. It was finished in the late summer and command was given to John Stoddard, who had served as clerk on Washington for two years.[86]

Kendrick and Stoddard sailed from Macau in September, 1792, planning to winter in Clayoquot Sound. Only a few days out they were caught in a violent typhoon, during which Washington was badly damaged and Avenger was lost, never to be seen again. Kendrick returned to Macau and took loans to pay for the major repairs Washington needed.[86]

About two months after this, the Columbia arrived at Macau. Kendrick sent a letter telling of the death of Stoddard and the crew of Avenger, news that the crew of Columbia would want to know. Otherwise Kendrick and Gray did not meet or communicate with each other. Gray found the price of furs very low and the second voyage of Columbia made little profit. On February 8, 1793, Columbia left for Boston.[86]

Through others Kendrick learned that Gray had fought with Wickaninnish's people in Clayoquot Sound, and had killed Wickaninnish's brother. He also learned of Gray's discovery of the Columbia River. In addition Kendrick learned about the British Vancouver Expedition under George Vancouver and the Butterworth Squadron under William Brown, and the hostility of both against American traders, especially Kendrick. In time Kendrick would find himself in fierce competition with Vancouver and Brown. Ultimately Kendrick would be killed by Brown in suspicious circumstances that Brown claimed was an accident.[86]

Kendrick learned much of this information from John Howell, who joined the crew of Washington as clerk in Macau. Howell, who was fluent in Spanish, had served as interpreter for Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra at Nootka Sound during the diplomatic negotiations with George Vancouver in 1792.[86] Howell arrived in Macau on the Margaret, under James Magee. Magee had hired Howell as a "historian". The two had collected native artifacts from the Pacific Northwest Coast and the Hawaiian Islands.[87] Howell would take command of Washington after Kendrick's death.[86]

In late February, 1793, Kendrick sailed the repaired Washington about 40 miles (64 km) east to Hong Kong Island. There, knowing that both Britain and Spain were seeking to lay claim to the Pacific Northwest and wanting to secure his own claims for the United States, Kendrick wrote to Thomas Jefferson. He described the land purchases he had made and included copies of the deeds. He wrote of his hope and belief that the United States would sanction and secure them, and protect them from Britain and Spain if necessary. He described the commercial advantages that could come from American possession of lands on the Northwest Coast, and suggested that a settlement there might be "worth the attention of some associated company, under the protection of the Government."[88] The letter was received by the State Department on October 24, 1793. Jefferson was already trying to organize an overland expedition, under André Michaux, to the Pacific coast. The under Michaux expedition never came to be, but the plan eventually resulted in the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Jefferson's reaction to Kendrick's letter is unknown, but the timing was not good. France had declared war on Britain and Spain just as Kendrick was writing the letter. Joseph Barrell had told Kendrick that any lands purchased could be authorized by Congress after the fact. Although this was true, in early 1793 Congress was unwilling to provoke Britain and Spain by annexing land on the Pacific coast.[88]

Kendrick, unaware of these events and knowing that at best there would be a long delay in any response, prepared to sail to the Pacific Northwest. He loaded Washington with trade goods, including cases of muskets, barrels of gunpowder, and ammunition. He left China and sailed to Nootka Sound, arriving in May, 1793.[88]

Northwest Coast 1793

Kendrick sailed across the Pacific from Macau, reaching Nootka Sound in late May, 1793, just days after George Vancouver had left. Salvador Fidalgo was the new commandant of the Spanish outpost, taking over after Bodeya y Quadra returned to San Blas, Mexico.[89]

Unlike Quadra, Fidalgo deeply mistrusted the Nuu-chah-nulth and other Northwest natives, and his attitude and behavior toward them had quickly led to unrest, undoing the friendly relations that had been built by Quadra and Alejandro Malaspina. Some of the Nuu-chah-nulth chiefs wanted to attack and destroy the Spanish post. Fidalgo knew that Kendrick was allied with the natives and had probably brought more firearms for them. After anchoring in Friendly Cove Kendrick went ashore with John Howell as translator. Fidalgo told Kendrick that he was under orders to deny Washington entry at Nootka Sound. Kendrick responding by threatening to "raise the Indians and drive [the Spanish] from their settlement" if Fidalgo gave him any trouble.[89]

Shortly after this meeting Kendrick took Washington to his old outpost at Marvinas Bay a few miles to the north. There he found the 90 ton American schooner Resolution and was surprised and delighted to find his son, Solomon Kendrick, now 22 years old, was second mate. He was also pleased with the very warm welcome he received from Chief Maquinna and the local natives.[89]

Solomon Kendrick had sailed with his father when they first came to the Pacific Northwest but was with the Columbia when Gray first sailed to China in 1789. Solomon brought news from home and how things were going for John's wife Huldah, his other children, and various friends. John and Solomon shared their stories about their many adventures at sea. One of Solomon's tales involved a stop at the Valparaíso, Chile, where he met Don Blas Gonzales, who had been stripped of rank for having helped Kendrick in 1788. Gonzales had spent four years trying to regain his post and his reputation, to no avail. He gave Solomon a letter begging John Kendrick to intercede on his behalf. Kendrick immediately wrote to Thomas Jefferson, describing what had happened and requesting whatever assistance Jefferson could provide for Gonzales. Jefferson asked the American ambassador in Spain to advocate for Gonzales, but ultimately no restoration was granted.[89]

In late June, 1793, Solomon Kendrick sailed with Resolution to trade in Haida Gwaii. John Kendrick traded locally in Nootka Sound, then went to Clayoquot Sound briefly, where a dispute between his allies Maquinna and Wickaninnish was threatening to turn violent. Kendrick returned to Marvinas Bay on July 13, 1793.[89] He made at least one more visit to Clayoquot Sound before departing for Hawaii in early October, 1793.[90]

Hawaii 1793–1794

Kendrick arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in late 1793. During the early winter he met with King Kamehameha on the Island of Hawaii. By January, 1794, he had given his carpenter John Boyd into the service of Kamehameha at Waiakea on Hilo Bay. Boyd began to work on building a ship for Kamehameha, planned to be a 40-ton, 36-foot (11 m) long armed sloop.[90]

As the work proceeded Kendrick toured the islands, trading and meeting the various men he had left. He had learned from Kamehameha that George Vancouver and William Brown had been trying to find a way to put the Hawaiian Islands under British control. Brown had already made a deal with Chief Kahekili that Brown believed gave him ownership of the islands of Maui, Lanai, Molokai, and Oahu. Kendrick returned to Kealakekua Bay on Hawaii and began making plans to disrupt the plans of Vancouver and Brown.[90]

On January 9, 1794, Vancouver's ships Discovery, Chatham, and Daedalus passed Kealakekua Bay as they sailed to Waiakea to meet with Kamehameha. When Vancouver met with Kamehameha he learned about Kendrick's shipwright John Boyd and the ship being built. This caused Vancouver dismay, in part because he had refused when Kamehameha had asked him for a ship. Vancouver also learned that Kendrick was at Kealakua Bay, attended by Kamehameha's aide and advisor John Young. Vancouver, eager to obstruct Kendrick, asked Kamehameha to come with him to Kealakekua Bay. The king declined, citing the makahiki season and its taboos, as well as his need to host various ceremonial events.[90]

Vancouver felt he needed Kamehameha with him to effectively proscribe Kendrick. After much persuading and inveigling Kamehameha agreed and went with Vancouver. On the way Vancouver convinced Kamehameha to let him take over the ship construction that Boyd had begun. He dismissed Boyd's abilities and offered to move the frame to Kealakekua and have his own carpenters build the rest of the ship with Vancouver's own supplies. Vancouver declared that the ship, to be named Britannia, would be a "man-of-war". This was hypocritical since Vancouver had for years denounced and complained about anyone providing weapons to native peoples. Nonetheless, Kamehameha was very pleased with the proposal.[90]

Vancouver's ships neared Kealakekua Bay on June 12, 1794. As they the crew worked to enter the bay John Young came with a friendly letter of welcome from Kendrick's agent John Howell, who was living ashore under the protection of Keeaumoku Pāpaiahiahi, chief of the Kona district and one of Kamehameha's highest ministers. While Vancouver's ships lay becalmed outside the bay Young brought Kamehameha ashore. As the ships—Discovery, Chatham, and Daedalus—made their way into the bay late in the day, Kendrick raised the US flag. As dusk turned to night Vancouver's ships anchored close to Washington.[90] The 90 ton, 60-foot (18 m) long Washington was dwarfed by the 340 ton, 99-foot (30 m) long, Discovery, 135 ton, 80-foot (24 m) Chatham, and the massive store ship Daedalus. In addition, Vancouver's men, numbering over 180, far outnumbered Kendrick's crew of less than 30.[91]

The next day Kendrick, John Howell, and Keeaumoku Pāpaiahiahi went aboard Discovery. Vancouver and Kendrick met face-to-face for the first time. Vancouver and Howell had met at Nootka Sound when Howell was serving as translator for Bodega y Quadra. Kendrick told Vancouver he was wintering in Hawaii and planning to return to the Pacific Northwest coast in the spring. Howell would stay in Hawaii to manage Kendrick's business. Vancouver knew that Kendrick had already sailed among the islands, inspecting his operations in Kauai and Oahu, and was continuing to strengthen his ties and trade with the Hawaiians. Among the items he had acquired was the largest feathered war cloak, about 9 feet (2.7 m) long and 24 feet (7.3 m) wide. Reportedly, he had traded his two stern chaser cannons for the cloak. He had also obtained chunks of ambergris worth thousands of dollars. His men on Kauai were collecting sandalwood and pearls and were starting to produce molasses, a valuable trade good on the Northwest Coast.[91]

The next day Kendrick and Howell again dined on Discovery. Kendrick wanted to talk about William Brown and his Butterworth Squadron. He knew that Vancouver, as a royal naval officer, was under certain constraints, while Brown, a private merchant, was free to do as he pleased. Kendrick knew that Vancouver and Brown had been coordinating with each other to some degree. He was also concerned about Brown's killing of natives at Clayoquot Sound in 1792, his hostility toward American traders, and his support of violence in Hawaii, especially on Kauai. But Vancouver and Brown were in close communication about the events on Kauai, and they agreed that the problem was Kendrick's presence and influence there. So Kendrick's attempt to convince Vancouver to rein in Brown went nowhere.[91]

Brown and Kendrick seemed to be supporting opposing sides in a conflict between Hawaiian chiefs. The exact situation is unclear due to the biased nature of historical sources. Brown had formally obtained various rights from Kahekili II, who ruled Maui and Oahu and had influence in Kauai. Brown believed that his agreement with Kahekili made him lord of all the islands except Hawaii, Kauai, and Niihau. Kendrick pressed Vancouver on whether Brown's deal with Kahekili was a private transaction or under royal authority. There is no record of Vancouver's reply, but there was hostility toward Kendrick among Vancouver's officers, and in general animosity toward Kendrick had become common among both Vancouver and Brown's men.[91]

On February 1, 1794, Vancouver's carpenters, having taken Boyd's ship frame, began working on the promised warship for Kamehameha. With Kamehameha increasingly pleased with him, Vancouver relaunched discussions about ceding Hawaii to Britain. Many chiefs met at a grand council on Discovery on February 19 and again on February 25. At the second council Kamehameha agreed to the cession of the island, according to Vancouver's journal. But when Vancouver required the removal of all of Kendrick's men, Kamehameha and the other chiefs refused, making the cession appear symbolic and hollow.[92]

Despite Vancouver's efforts, Kendrick was able to proceed as if nothing had happened. He ignored both Vancouver's claim over the Island of Hawaii and Brown's claim over the islands from Maui to Oahu.[92]

Vancouver left Kealakekua Bay on February 26, 1794, and briefly cruised among the Hawaiian Islands. He was finishing his survey of the islands and evaluation of harbors, as well as looking to strengthen British power and drive Kendrick away. Kendrick, however, sailed ahead, arriving at key harbors and meeting with chiefs before Vancouver. He spent five days at Waikiki (part of Honolulu today) with Kahekili and his chiefs. When Vancouver arrived the chiefs would not even meet with him.[92]

When Vancouver reached Kauai he found Kendrick at Waimea, having arrived two days before. Vancouver met with Kendrick and tried to pressure him into withdrawing his men. Kendrick dissembled and Vancouver thought he had succeeded. But when Vancouver finally left for the Pacific Northwest coast, on March 14, 1794, Kendrick and his men remained in the Hawaiian Islands.[92]

On February 24, 1794, Brown had set sail from China, making for the Pacific Northwest coast. Vancouver and Brown encountered each other on July 3, 1794, near Cross Sound, southeast Alaska. Brown had just arrived with the Jackall. Vancouver told him of his recent experiences in Hawaii, and his failure to seize or drive off the Americans, as Brown had been hoping.[93]

Not long after Vancouver left Hawaii, Kendrick also sailed to the Pacific Northwest coast. He found the situation at Nootka Sound bleak. Chief Maquinna's people had suffered a hard winter and famine. The conflict with Wickaninnish was ongoing. Maquinna wanted to move his people closer to the Spanish fort at Friendly Cove, but the new commandant, Ramón Saavedra Guiráldez y Ordónez, refused.[93] Kendrick soon sailed north, seeking sea otter skins, which had become scarce at Nootka and Clayoquot. He cruised the Alexander Archipelago, acquiring furs. At the Tlingit settlement that would later become Sitka he disposed all his remaining trade goods, including some molasses his men had made in Kauai. Then he headed back to Nootka Sound.[93]

In early September, 1794, Kendrick was anchored in Friendly Cove, Nootka Sound, along with three Spanish ships and two British trading ships, including Prince Lee Boo, one of Brown's ships. Vancouver and his three ships soon arrived as well.[93] He found his eldest son, John, now called Juan Kendrick, was there, having arrived as master of the Spanish frigate Aranzazu. He also learned that the Resolution had disappeared and his son Solomon was probably dead.[94] Neither John nor his son Juan knew that Resolution had been attacked and captured by Chief Cumshewa and possibly Kendrick's old enemy Koyah. All but one of the crew were killed, including Solomon Kendrick.[95][96] Juan Kendrick learned about this later and in 1799, with others who had lost friends or family members on Resolution, exacted revenge.[94][95]

At Friendly Cove Kendrick continued to prepared Washington for another voyage to China. It would be his fifth voyage across the Pacific Ocean. His situation seemed good. He had two seasons of furs in the hold, along with more than 80 pounds (36 kg) of ambergris from Oahu. The ambergris alone was worth about $16,000 in Macau. Awaiting him in Macau was a letter from Joseph Barrell, who had been convinced by Hoskins that Kendrick was an honest man despite the accusations of Gray and Haswell. In the letter Barrell offerred Kendrick ownership of Washington, discharge from service to Barrell, and complete independence, if Kendrick could send 400 chests of tea, valued at about $14,000. But Kendrick would be killed before reaching Macau.[94]

In September, 1794, Juan Kendrick was given command of Aranzazu and sailed for San Blas. On the way he stopped at Monterey, California, thus becoming the first American known to have set foot in California.[97] Being part of the Spanish Navy's San Blas Department, it was probably not his first time in California.

On October 5, 1794, William Brown arrived on Jackall. He learned that he could no longer count on help from Vancouver, who with failing health was soon to return to England. Brown also learned that Kendrick remained a problem for the British on the Northwest Coast as well as in Hawaii, and that if anything was to be done, it was up to Brown himself.[94]

On October 16, 1794, Vancouver left for Monterey. The next day the Spanish also left, abandoning their outpost at Nootka Sound, Santa Cruz de Nuca, as required by the Third Nootka Convention. Brown's Jackall and Prince Lee Boo soon left for Oahu, leaving only Lady Washington and the Spanish packet ship San Carlos. Around the end of October, 1794, Kendrick finally sailed for Hawaii.[94]

Hawaii and death

In December, 1794, Kendrick anchored at his usual mooring in Kealakekua Bay. Trade was good and he continued to build support among the Hawaiians. After a few days dire news came from Oahu. War was breaking out again. Kahekili had died in July and rivalry among his heirs had turned violent. His son Kalanikūpule, King of Oahu, was fighting Kahekili's brother Kaeokulani (also called Kaeo) over succession to the Kingdom of Maui.[98]

Further, when Kahekili died his agreements with William Brown ended, but Brown was trying to extend the deal by offering military support to Kalanikūpule. Brown's actions fueled increasing tensions. In late November, 1794, Brown had sailed to Honolulu and put his ships and men into the service of Kalanikūpule. A major battle was imminent and Brown knew he would lose his claims of lordship if Kaeo defeated Kalanikūpule. By the end of November Kaeo and Kalanikūpule's forces were skirmishing around Pearl Harbor.[98]