Newar language

Newar (English: /niːˈwɑːr/)[4] or Newari,[5] known officially in Nepal as Nepal Bhasa,[6] is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the Newar people, the indigenous inhabitants of Nepal Mandala, which consists of the Kathmandu Valley and surrounding regions in Nepal.

| Newar | |

|---|---|

| Nepal Bhasa | |

| नेवाः भाय्, Nevāh Bhāy | |

The word "Nepal Bhasa" written in the Ranjana script and the Prachalit Nepal script | |

| Native to | Nepal |

| Ethnicity | 1.26 million Newars (2001 census?)[1] |

Native speakers | 860,000 (2011 census)[2] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

Early form | |

| Dialects |

|

| Ranjana script, Pracalit script and various in the past, Devanagari currently | |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Nepal Bhasa Academy |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | new Nepal Bhasa, Newari |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:new – Newarinwx – Middle Newar |

new Newari | |

nwx Middle Newar | |

| Glottolog | newa1247[3] |

Although "Nepal Bhasa" literally means "Nepalese language", the language is not the same as Nepali (Devanāgarī: नेपाली), the country's current official language. The two languages belong to different language families (Sino-Tibetan and Indo-European, respectively), but centuries of contact have resulted in a significant body of shared vocabulary. Both languages have official status in Kathmandu Metropolitan City.

Newar was Nepal’s administrative language from the 14th to the late 18th century. From the early 20th century until democratisation, Newar suffered from official suppression.[7] From 1952 to 1991, the percentage of Newar speakers in the Kathmandu Valley dropped from 75% to 44%[8] and today Newar culture and language are under threat.[9] The language has been listed as being "definitely endangered" by UNESCO.[10]

Name

The earliest occurrences of the name Nepālabhāṣā (Devanāgarī: नेपालभाषा) or Nepālavāc (Devanāgarī: नेपालवाच) can be found in the manuscripts of a commentary to the Nāradasaṃhitā, dated 1380 AD, and a commentary to the Amarkośa, dated 1386 AD.[11][12] Since then, the name has been used widely on inscriptions, manuscripts, documents and books. The colloquial form is "Newah Bhay" (Devanāgarī: नेवा: भाय्, IAST: Nevāḥ Bhāy).

In the 1920s, the name of the language known as Khas Kura,[13] Gorkhali or Parbatiya[14] was changed to Nepali,[15] and the language began to be officially referred to as Newari while the Newars continued using the original term.[16] Conversely, the term Gorkhali in the former national anthem entitled "Shreeman Gambhir" was changed to Nepali in 1951.[17]

On 8 September 1995, following years of lobbying to use the old name, the government decided that the name Nepal Bhasa should be used instead of Newari.[18] However, the decision was not implemented, and on 13 November 1998, the Minister of Information and Communication issued another directive to use the name Nepal Bhasa instead of Newari.[19] However, the Central Bureau of Statistics has not been doing so.[20]

Geographic distribution

Newar is spoken by over a million people in Nepal according to the 2001 census.

- In Nepal: Kathmandu Valley (including Kathmandu, Lalitpur, Bhaktapur and Madhyapur Thimi municipalities), Dolakha District, Banepa, Dhulikhel, Bandipur, Bhimphedi (Makwanpur), Panauti, Palpa, Trishuli, Nuwakot, Bhojpur, Chitlang, Narayangarh, Chitwan.[21][22]

- In India: West Bengal[23]

- In Tibet: Khasa

With an increase in emigration, various bodies and societies of Newar-speaking people have emerged in countries such as the US, the UK, Australia, and Japan.

Relationship with other Tibeto-Burman languages

The exact placement of Newar within the Tibeto-Burman language family has been a source of controversies and confusion. The linguist Warren W. Glover classified Newar as a part of Bodic subdivision using Shafer's terminology.[24] Professor Van Driem classified Newar within the Mahakiranti grouping but he later retracted his hypothesis in 2003. Moreover, he proposed a new grouping called "Maha-Newari" which possibly includes Baram–Thangmi.[25]

T. R. Kansakar attributes the difficulty about the placement of Newar to the inability of scholars to connect it with the migration patterns of the Tibeto-Burman speakers. Since Newar separated from rest of the family very early in history, it is difficult or at least arbitrary to reconstruct the basic stratum that contributed to present day Newar speech. He underscored the point that the language evolved from mixed racial/linguistic influences that do not lend easily to a neat classification.[26]

A classification (based on Glover's) indicating a percentage of shared vocabulary within the labeled branch and an approximate time of split:

|

Indo-Aryanized (~50-60% lexicons) |

ɫ "%" indicates lexical similarity/common vocabulary between Newar and the other languages in the branch. The date indicates an approximate time when the language diverged.

ɞ Van Driem labelled this branch as "Parakiranti" and included it together with Kiranti branch to form Maha Kiranti group. However, he would later drop this hypothesis.

ʌ All languages within this branch have extensive Indo-Aryan vocabulary. It is hypothesised that either ancient IndoAryan admixture happened before Newar-Thangmi-Baram split or that Thangmi-Baram borrowed through Newari.[27]

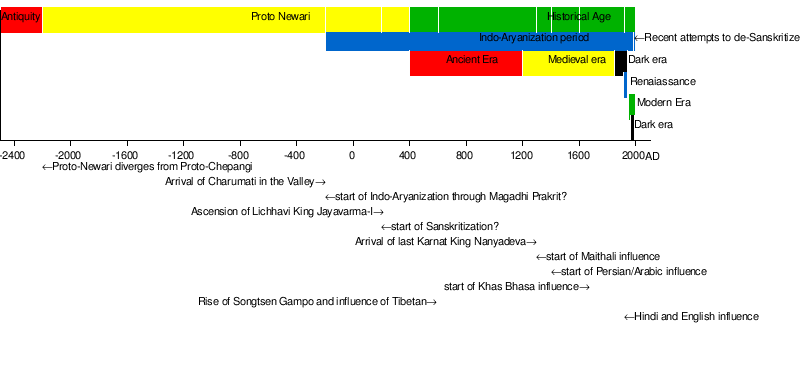

History and development

According to the linguist, Glover, Newari and the Chepang language must have diverged around 2200 BC. It is estimated that Newari shares 28% of its vocabulary with Chepang. At the same time, a very large and significant proportion of Newari vocabulary is Indo-European in origin, by one estimate more than 50%, indicating an influence of at least 1600 years from Indo-European languages, first from Sanskrit, Maithili, Persian, and Urdu and today from Hindi, Nepali and English.[28]

Newar words appeared in Sanskrit inscriptions in the Kathmandu Valley for the first time in the fifth century. The words are names of places, taxes and merchandise indicating that it already existed as a spoken language during the Licchavi period (approximately 400-750 AD).[29]

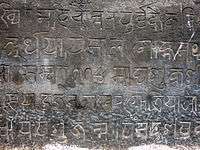

Inscriptions in Newar emerged from the 12th century, the palm-leaf manuscript from Uku Bahah being the first example.[30] By the 14th century, Newar had become an administrative language as shown by the official proclamations and public notices written in it. The first books, manuals, histories and dictionaries also appeared during this time. The Gopalarajavamsavali, a history of Nepal, appeared in 1389 AD.[31] From the 14th century onwards, an overwhelming number of stone inscriptions in the Kathmandu Valley, where they are a ubiquitous element at heritage sites, are in Newar.[32]

Newar developed as the court and state language of Nepal from the 14th to the late 18th centuries.[15] It was the definite language of stone and copper plate inscriptions, royal decrees, chronicles, Hindu and Buddhist manuscripts, official documents, journals, title deeds, correspondence and creative writing. Records of the life-cycle ceremonies of Malla royalty and the materials used were written in Newar.[33]

The period 1505–1847 AD was a golden age for Newar literature. Poetry, stories, epics, and dramas were produced in great numbers during this time which is known as the Classical Period. Since then it entered a period of decline due to official disapproval and oftentimes outright attempts to stamp it out.

Newar can be classified into the old and new eras. Although there is no specific demarcation between the two, the period 1846–1941 AD during the Rana regime is taken as the dividing period between the two.[34]

Ancient era

An example of the language of the ancient period is provided by the following line from the palm-leaf manuscript from Uku Bahah which dates from 1114 AD. It is a general discussion of business transactions.

- छीन ढाको तृसंघष परिभोग। छु पुलेंग कीत्य बिपार वस्त्र बिवु मिखा तिवु मदुगुन छु सात दुगुनव ल्है

- chīna ḍhākō tr̥saṃghaṣa paribhōga, chu pulēṃga kītya bipāra vastra bivu mikhā tivu maduguna chu sāta dugunava lhai

Medieval era

The language flourished as an administrative and literary language during the medieval period.[15] Noted royal writers include Mahindra Malla, Siddhi Narsingh Malla, and Jagat Prakash Malla. An example of the language used during this period is provided by the following lines from Mooldevshashidev written by Jagat Prakash Malla.[35]

- धु छेगुकि पाछाव वाहान

- dhu chēguki pāchāva vāhāna

- तिलहित बिया हिङ लाहाति थाय थायस

- tilahita biyā hiŋa lāhāti thāya thāyasa

The verse is a description of Shiva and the use of a tiger skin as his seat.

Dark age

Newar began to be sidelined after the Gorkha conquest of Nepal and the ouster of the Malla dynasty by the Shah dynasty in the late 18th century. Since then, its history has been one of constant suppression and struggle against official disapproval.[36]

Following the advent of the Shahs, the Gorkhali language became the court language,[37] and Newar was replaced as the language of administration.[38] However, Newar continued to remain in official use for a time as shown by the 1775 treaty with Tibet which was written in it.[15] A few of the new rulers cultivated the language. Kings Prithvi Narayan Shah, Rana Bahadur and Rajendra Bikram Shah composed poetry and wrote plays in it.

Newar suffered heavily under the repressive policy of the Rana dynasty (1846–1951 AD) when the regime attempted to wipe it out.[39][40] In 1906, legal documents written in Newar were declared unenforceable, and any evidence in the language was declared null and void.[41] The rulers forbade literature in Newar, and writers were sent to jail.[42] In 1944, Buddhist monks who wrote in the language were expelled from the country.[43][44]

Moreover, hostility towards the language from neighbours grew following massive migration into the Kathmandu Valley leading to the indigenous Newars becoming a minority.[45] During the period 1952 to 1991, the percentage of the valley population speaking Newar dropped from 74.95% to 43.93%.[46] The Nepal Bhasa movement arose as an effort to save the language.

Nepal Bhasa movement

Newars have been fighting to save their language in the face of opposition from the government and hostile neighbours from the time of the repressive Rana regime till today.[47] The movement arose against the suppression of the language that began with the rise of the Shah dynasty in 1768 AD, and intensified during the Rana regime (1846–1951) and Panchayat system (1960–1990).[48]

At various times, the government has forbidden literature in Newar, banned the official use and removed it from the media and the educational system.[49] Opponents have even petitioned the Supreme Court to have its use barred.

Activism has taken the form of publication of books and periodicals to public meets and protest rallies. Writers and language workers have been jailed or expelled from the country, and they have continued the movement abroad. The struggle for linguistic rights has sometimes combined with the movement for religious and political freedom in Nepal.

Renaissance era

The period between 1909 and 1941 is considered as the renaissance era of Newar.[50] During this period, a few authors braved official disapproval and started writing, translating, educating and restructuring the language. Writers Nisthananda Bajracharya, Siddhidas Mahaju, Jagat Sundar Malla and Yogbir Singh Kansakar are honored as the Four Pillars of Nepal Bhasa. Shukraraj Shastri and Dharmaditya Dharmacharya were also at the forefront of the Renaissance.

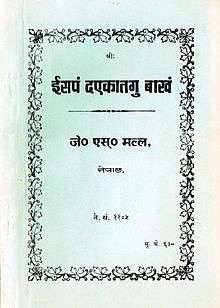

In 1909, Bajracharya published the first printed book using movable type. Shastri wrote a grammar of the language entitled Nepal Bhasa Vyakaran, the first one in modern times. It was published from Kolkata in 1928. His other works include Nepal Bhasa Reader, Books 1 and 2 (1933) and an alphabet book Nepali Varnamala (1933).[51]

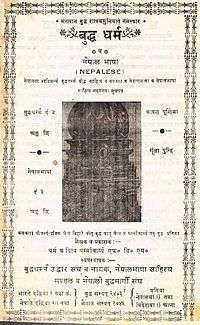

Mahaju's translation of the Ramayan and books on morals and ethics, Malla's endeavours to impart education in the native language and other literary activities marked the renaissance. Dharmacharya published the first magazine in Newar Buddha Dharma wa Nepal Bhasa ("Buddhism and Nepalese") from Kolkata in 1925. Also, the Renaissance marked the beginning of the movement to get official recognition for the name "Nepal Bhasa" in place of the Khas imposed term "Newari".

Some of the lines of Mahaju read as follows:

- सज्जन मनुष्या संगतनं मूर्ख नापं भिना वै

- sajjana manuṣyā saṃgatanaṃ mūrkha nāpaṃ bhinā vai

- पलेला लपते ल वंसा म्वति थें ल सना वै

- palēlā lapatē la vaṃsā mvati thēṃ la sanā vai

The verse states that even a moron can improve with the company of good people just like a drop of water appears like a pearl when it descends upon the leaves of a lotus plant.

Modern Newar

Jail years

The years 1941–1945 are known as the jail years for the large number of authors who were imprisoned for their literary or political activities. It was a productive period and resulted in an outpouring of literary works.

Chittadhar Hridaya, Siddhicharan Shrestha and Phatte Bahadur Singh were among the prominent writers of the period who were jailed for their writings. While in prison, Hridaya produced his greatest work Sugata Saurabha,[52] an epic poem on the life of Gautama Buddha.[42] Shrestha wrote a collection of poems entitled Seeswan ("Wax Flower", published in 1948) among other works. Singh (1902–1983) was sentenced to life imprisonment for editing and publishing an anthology of poems by various poets entitled Nepali Bihar.[53]

The efforts of Newar authors coincided with the revival of Theravada Buddhism in Nepal, which the rulers disliked equally. In 1946, the monks who had been exiled by the Ranas in 1944 for teaching Buddhism and writing in Newar were allowed to return following international pressure. Restrictions on publication were relaxed, and books could be published after being censored. The monks wrote wide-ranging books on Buddhism and greatly enriched the corpus of religious literature.[54][55]

Outside the Kathmandu Valley in the 1940s, poets like Ganesh Lal Shrestha of Hetauda composed songs and put on performances during festivals.[56]

The 1950s

Following the overthrow of the Rana dynasty and the advent of democracy in 1951, restrictions on publication in Newar were removed. Books, magazines and newspapers appeared. A daily newspaper Nepal Bhasa Patrika began publication in 1955.[57] Textbooks were published and Newar was included in the curriculum. Nepal Rastriya Vidhyapitha recognised Newar as an alternative medium of instruction in the schools and colleges affiliated to it.

Literary societies like Nepal Bhasa Parisad were formed and Chwasa: Pasa returned from exile.[36] In 1958, Kathmandu Municipality passed a resolution that it would accept applications and publish major decisions in Newar in addition to the Nepali language.[58]

Second dark age

Democracy lasted for a brief period, and Newar and other languages of Nepal entered a second dark age with the dissolution of parliament and the imposition of the Panchayat system in 1960. Under its policy of "one nation, one language", only the Nepali language was promoted, and all the other languages of Nepal were suppressed as "ethnic" or "local" languages.[59]

In 1963, Kathmandu Municipality's decision to recognize Newar was revoked. In 1965, the language was also banned from being broadcast over Radio Nepal.[60] Those who protested against the ban were put in prison, including Buddhist monk Sudarshan Mahasthavir.

The New Education System Plan brought out in 1971 eased out Nepal's other languages from the schools in a bid to diminish the country's multi-lingual traditions.[61] Students were discouraged from choosing their native language as an elective subject because it was lumped with technical subjects.[47] Nepal's various languages began to stagnate as the population could not use them for official, educational, employment or legal purposes.

Birat Nepal Bhasa Sahitya Sammelan Guthi (Grand Nepal Bhasa Literary Conference Trust), formed in 1962 in Bhaktapur, and Nepal Bhasa Manka Khala, founded in 1979 in Kathmandu, are some of the prominent organizations that emerged during this period to struggle for language rights. The names of these organizations also annoyed the government which, on one occasion in 1979, changed the name of Brihat Nepal Bhasa Sahitya Sammelan Guthi in official media reports.[62]

Some lines by the famous poet Durga Lal Shrestha of this era are as follows:[63]

- घाः जुयाः जक ख्वइगु खः झी

- स्याःगुलिं सः तइगु खः

- झी मसीनि ! झी मसीनि !

- धइगु चिं जक ब्वैगु खः

- We are crying because we are wounded

- We are shouting because of the pain

- All in all, we are demonstrating

- That we are not dead yet.

Post-1990 People's Movement

After the 1990 People's Movement that brought the Panchayat system to an end, the languages of Nepal enjoyed greater freedom.[64] The 1990 constitution recognized Nepal as a multiethnic and multilingual country. The Nepali language in the Devanagari script was declared the language of the nation and the official language. Meanwhile, all the languages spoken as native languages in Nepal were named national languages.[65]

In 1997, Kathmandu Metropolitan City declared that its policy to officially recognize Nepal Bhasa would be revived. The rest of the city governments in the Kathmandu Valley announced that they too would recognize it. However, critics petitioned the Supreme Court to have the policy annulled, and in 1999, the Supreme Court quashed the decision of the local bodies as being unconstitutional.[66]

Post-2006 People's Movement

A second People's Movement in 2006 ousted the Shah dynasty and Nepal became a republic which gave the people greater linguistic freedom. The 2007 Interim Constitution states that the use of one's native language in a local body or office shall not be barred.[67] However, this has not happened in practice. Organizations with names in Newar are not registered, and municipality officials refuse to accept applications written in the language.[68][69]

The restoration of democracy has been marked by the privatization of the media. Various people and organizations are working for the development of Newar. Newar has several newspapers, a primary level curriculum, several schools, several FM stations (selected time for Newar programs), regular TV programs and news (on Image TV Channel), Nepal Bhasa Music Award (a part of Image Award) and several websites (including a Wikipedia in Nepal Bhasa[70]).

The number of schools teaching Newar has increased, and Newar is also being offered in schools outside the Kathmandu Valley.[71]

Outside Nepal Mandala

Inscriptions written in Newar occur across Nepal Mandala and outside.

In Gorkha, the Bhairav Temple at Pokharithok Bazaar contains an inscription dated Nepal Sambat 704 (1584 AD), which is 185 years before the conquest of the Kathmandu Valley by the Gorkha Kingdom. The Palanchowk Bhagawati Temple situated to the east of Kathmandu contains an inscription recording a land donation dated Nepal Sambat 861 (1741 AD).[72]

In Bhojpur in east Nepal, an inscription at the Bidyadhari Ajima Temple dated Nepal Sambat 1011 (1891 AD) records the donation of a door and tympanum. The Bindhyabasini Temple in Bandipur in west Nepal contains an inscription dated Nepal Sambat 950 (1830 AD) about the donation of a tympanum.[73]

Outside Nepal, Newar has been used in Tibet. Official documents and inscriptions recording votive offerings made by Newar traders have been found in Lhasa.[74] A copper plate dated Nepal Sambat 781 (1661 AD) recording the donation of a tympanum is installed at the shrine of Chhwaskamini Ajima (Tibetan: Palden Lhamo) in the Jokhang Temple.[75]

Literature

Newar literature has a long history. It has the one of the oldest literature of the Sino-Tibetan languages (together with Chinese, Tibetan, Tangut, Burmese, Yi, etc.)

Drama

Dramas are traditionally performed in open Dabu (stage). Most of the traditional dramas are tales related to deities and demons. Masked characters and music are central elements to such dramas. Most of them are narrated with the help of songs sung at intervals. Such dramas resemble dance in many cases. The theme of most dramas is the creation of a social well-being with morals illustrating the rise, turbulence, and fall of evil. There is fixed dates in the Nepal Sambat (Nepal Era) calendar for the performance of specific drama. Most of the dramas are performed by specific Guthis.

Poetry

Poetry writing constituted a pompous part of medieval Malla aristocracy. Many of the kings were well-renowned poets. Siddhidas Mahaju and Chittadhar Hridaya are two great poets in the language.

Prose fiction

Prose fiction in Newar is a relatively new field of literature compared to other fields. Most fiction was written in poetry form until the medieval era. Consequently, almost all prose fiction belongs to the modern Newar era. Collections of short stories in Newar are more popular than novels.

Story

The art of verbal story telling is very old in Newar. There are a variety of mythical and social stories that have aided in establishing the norm of Kathmandu valley. Stories ranging from the origin of Kathmandu valley to the temples of the valley and the important monuments have been passed down verbally in Newar and very few exist in written form. However, with an increase in the literacy rate and an awareness among the people, folklore stories are being written down. Stories on other topics are also becoming popular.

Dialects

Kansakar (2011)[76] recognizes three main Newar dialect clusters.

- Western: Tansen (Palpa), Butwal, Old Pokhara, Dumre, Bandipur, Ridhi (Gulmi), Baglung, Dotili / Silgadi

- Central: Kathmandu, Lalitpur, Bhaktapur, Thimi, Kirtipur, Chitlang, Lele, Balaju, Tokha, Pharping, Thankot, Dadikot, Balami, Gopali, Bungamati, Badegaon, Pyangaon, Chapagaon, Lubhu, Sankhu, Chakhunti, Gamtsa Gorkha, Badikhel (Pahari), Kavrepalanchok District dialects (Banepa, Nala, Sangaa, Chaukot, Panauti, Dhulikhel, Duti), Khampu, Khopasi

- Eastern: Chainpur, Dharan, Dolakha, Sindhupalchok, Taplejung, Terhathum, Bhojpur, Dhankuta, Narayangadh, Jhapa, Ilam

Kansakar (2011) also gives the following classification of Newar dialects based on verb conjugation morphology.

- Central

- Kathmandu, Lalitpur, Kirtipur, Chitlang, Lele

- Bhaktapur, Thimi

- Eastern

- Dolakha, Tauthali, Jethal, Listikot, Doti

- Pahari (Badikhel)

The main dialects of Newar are:

- Dolkhali (Dolakha)

- This is the most preserved form of the language and resembles the old Newar.

- Sindhupalchok Pahri

- This dialect, also known as Pahri or Pahari, is found in the Sindhupalchok District of central Nepal.[2] It a similar vocabulary as the Yala subdialect of Yen-Yala-Kyepu dialect. However, the language is spoken with a Tamang language tone.

- Chitlang

- This dialect is used in Chitlang, a place south of Kathmandu valley in Makawanpur district. This is one of the biggest Newar bastions at Chitlang. Balami caste predominates there. Recently a new committee named "Balami Samaaj" has been established to give an identity rather than Newar but as the government has categorized Balami as Newar, this attempt fails.

- Kathmandu

- Kathmandu dialect is one of the dominant form of language and very close to the standard form of language used in academics and media. It is also the most widely used dialect. It is especially spoken in Kathmandu. It is very similar to the Lalitpur dialect.

- Lalitpur

- Lalitpur dialect is the most dominant form of language and is the standard form of language used in academics and media. It is also very widely used dialect. It is especially spoken in Lalitpur.

- Bhaktapur

- Also known as Khvapa Bhāy ख्वप: भाय्, this dialect is more archaic than the standard. Variations exist in the use of this form of language in Bhaktapur, Banepa, Panauti, and Dhulikhel.

Religions play a register-like role in dialectical diversity though they are minor. It has been recorded from the Malla period. Hinduism and Buddhism were present at that age and few words in Hinduism and Buddhism of Newar differs. With the recent growth of Christianity, Islam, other religions, and atheism in Nepal, the diversity in the speech registers regarding religious terminology has become more extended, such as omitting the word dyaḥ (द्यः, 'god') after the name of a deity by many people whereas it is retained in Hinduism and Buddhism. For example, Lord Ganesha is said as Ganedyaḥ (गनेद्यः) by Hindus and Buddhists but only Gane (गने) by other people.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | (Alveolo-) palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ* | tɕ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ* | tɕʰ | kʰ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɖ* | dʑ | ɡ | ||

| murmured | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ* | dʑʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| Fricative | s | h | |||||

| Nasal | voiced | m | n | ŋ | |||

| murmured | mʱ | nʱ | |||||

| Tap | voiced | (ɾ) | (ɽ)* | ||||

| murmured | (ɾʱ) | (ɽʱ)* | |||||

| Lateral | voiced | l | |||||

| murmured | lʱ | ||||||

| Approximant | voiced | w | j | ||||

| murmured | wʱ | jʱ | |||||

*-only occur in Dolakha Newar.

- Tap consonants mainly occur as word-medial alternates of /t/, /d/, /dʱ/ or /ɖ/ (in Dolakha only).

- /s/ can be heard as [ɕ] when occurring before front vowels/glide /i, e, j/.

- In Kathmandu Newar, /ŋ/ only occurs as word-final.

- Affricates /tɕ, dʑ/ can also shift to retracted sounds [t̠s̠, d̠z̠] when occurring before back vowels.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | nasal | short | long | nasal | short | long | nasal | |

| Close | i | iː | ĩ | u | uː | ũ | |||

| Close-mid | e | eː | ẽ | o | oː | õ | |||

| Mid | ə | əː | ə̃ | (ɔ) | (ɔː) | ||||

| Open-mid | ɛː | ɛ̃ː | |||||||

| Open | æː | æ̃ː | a | aː | ã | ɑ* | ɑː* | ɑ̃* | |

*-only occur in Dolakha Newar.[77][78][79]

- /o, oː/ and /u/ can also be heard as [ɔ, ɔː], and [ʊ].

- In Dolakha Newar, the back vowel sound /ɑ/ can also range to [ʌ], [ə].

- The following nasal vowels can also be distinguished in vowel length as /ĩː ẽː ə̃ː ãː õː ũː/.

Writing systems

Newar is now almost always written in the Devanagari script. The script originally used, Nepal Lipi or "Nepalese script", fell into disuse at the beginning of the 20th century when writing in the language and the script was banned.[80]

Nepal Lipi, also known as Nepal Akha,[81] emerged in the 10th century. Over the centuries, a number of variants of Nepali Lipi have appeared.

Nepal has been written in a variety of abugida scripts:

- Brahmi script

- Gupta script

- Kutila script

- Prachalit script

- Ranjana script

- Bhujinmol script

- Kunmol script

- Kwenmol script

- Litumol script

- Hinmol script

- Golmol script

- Pachumol script

- Devanagari script

Devanagari is the most widely used script at present, as it is common in Nepal and India. Ranjana script was the most widely used script to write Classical Nepalese in ancient times. It is experiencing a revival due to the recent rise of cultural awareness. The Prachalit script is also in use. All used to write Nepal but Devanagari are descended from a script called the Nepal script.

Ranjana alphabet

Classical Nepalese materials written in Ranjana can be found in present-day Nepal, East Asia, and Central Asia.

Consonants

Special consonant in Nepal omitted.

Vowels

There are 3 series of vowel diacritics - the [ka]-like system, the [ɡa]-like system, and the [ba]-like system.

- Use the [ka]-like system when applying to [ka], [d͡ʑa], [m̥a], [hʲa], [kʂa], and [d͡ʑȵa]

- Use the [ɡa]-like system when applying to [ɡa], [kʰa], [ȵa], [ʈʰa], [ɳa], [tʰa], [dʱa], and [ɕa]

- Use the [ba]-like system when applying to [ba], [ɡʱa], [ŋa], [t͡ɕa], [t͡ɕʰa], [d͡ʑʱa], [ʈa], [ɖa], [ɖʱa], [ta], [da], [na], [n̥a], [pa], [pʰa], [ba], [bʱa], [ma], [ja], [ra], [hra], [la], [l̥a], [va], [vʱa], [ʂa], [sa], [ha], [t͡r̥a]

Note that many of the consonants mentioned above (e.g. [bʱa], [ɖʱa], [ɡʱa], etc.) occur only in loan words and mantras.

Consonant-free vowels

Numerals

- The numerals used in Ranjana script are as follows (from 0 to 9):

Devanagari orthography

Modern Newar is written generally with the Devanagari script, although formerly it was written in the Ranjana and other scripts. The letters of the Nagari alphabet are traditionally listed in the order vowels (monophthongs and diphthongs), anusvara and visarga, stops (plosives and nasals) (starting in the back of the mouth and moving forward), and finally the liquids and fricatives, written in IAST as follows (see the tables below for details):

- a ā i ī u ū ṛ ṝ ḷ ḹ; e ai o au

- ṃ ḥ

- k kh g gh ṅ; c ch j jh ñ; ṭ ṭh ḍ ḍh ṇ; t th d dh n; p ph b bh m

- y r l v; ś ṣ s h

Kathmandu Newar does not use ñ for the palatal nasal but instead writes this sound with the ligature ⟨ny⟩ as for example in the word nyā 'five'. Orthographic vowel length represents a difference of vowel quality, and in fact vowel length is indicated with the visarga after the vowel an (e.g. khāḥ 'ís') and with other vowels is written with the independent vowel letter (which would not be permitted e.g. in Sanskrit), for example mhii:ga: 'day after tomorrow'.

Vowels

The vowels, called mā ākha (माआखः), meaning "mother letters", used in Newar are:

| Orthography | अ | अः | आ | आः | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ऋ | ॠ | ऌ | ॡ | ए | ऐ | ओ | औ | अँ | अं | अय् | आय् | एय् |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman | a | a: | aa | aa: | i | ii | u | uu | ri | rii | lri | lrii | e | ai | o | au | an | aN | ay | aay | ey |

Even though ऋ, ॠ, ऌ, ॡ are present in Newar, they are rarely used. Instead, some experts suggest including अय् (ay) and आय् (aay) in the list of vowels.[82]

Consonants

The consonants, called bā ākha (बाआखः), meaning "father letters", used in Newar are:

| क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | ङ्ह | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /k/a | /kʰ/a | /g/a | /gʱ/a | /ŋ/a | /ŋ/ha | |||

| च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ||||

| /c/a | /cʰ/a | /ɟ/a | /ɟʱ/a | /ɲ/a | ||||

| ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | ||||

| /ʈ/a | /ʈʰ/a | /ɖ/a | /ɖʱ/a | /ɳ/a | ||||

| त | थ | द | ध | न | न्ह | |||

| /t̪/a | /t̪ʰ/a | /d̪/a | /d̪ʱ/a | na | nha | |||

| प | फ | ब | भ | म | म्ह | |||

| /p/a | /pʰ/a | /b/a | /bʱ/a | ma | mha | |||

| य | ह्य | र | ह्र | ल | ल्ह | व | व्ह | |

| ya | hya | ra | hra | la | lha | va or wa | wha | |

| श | ष | स | ह | |||||

| /ɕ/a | /ʃ/a | sa | ha | |||||

| क्ष | त्र | ज्ञ | ||||||

| ksha | tra | /ɡɲ/a | ||||||

ङ्ह, न्ह, म्ह, ह्य, ह्र, ल्ह and व्ह are sometimes included in the list of consonants as they have a specific identity in Nepal.

The use of ङ and ञ was very common in the old form of language. However, in the new form, especially in writing, the use of these characters has diminished. The use of ण, त, थ, द, ध, न, श, ष, क्ष, त्र, ज्ञ is limited by the new grammar books to the loan words only.

Complex/compound consonants

Besides the consonants mentioned above, combined consonants called chinā ākha (चिना आखः) are used.

Numerals

- The same numericals in Devnagari are:

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Grammar

Newar language is one of the few Tibeto-Burman languages with a clusivity distinction.

Sentence structure

Statement sentence-

This language is a SOV (subject–object–verb) language. For instance, "My name is Bilat (Birat)" is "Jigu Na'aa Bilat Khaa'a " which word by word translation becomes, "My (Jigu) Name (Na'aa) Bilat is (Khaa'a)".

Interrogative sentence-

Wh-question:

In the case of Newar language, Wh-questions are rather "G-questions" with "when/which" being replaced by "Gublay/Gugu" respectively. There is an additional "Guli" which is used for "How much/How many". A S-word "Soo" is used for "who". "Chhoo/Schoo (with a silent 's')" is used for "What", and "Gathey" is used for "How".

Affixes

Suffix- "Chaa" and "Ju" are two popular suffixes. "Chaa" is added to signify "junior" or "lesser". But when added to a name, it is used derogatorily. For example, kya'ah-chaa means nephew where "chaa" is being added to kya'ah(son). When added to name like Birat for "Birat-chaa", it is being used derogatorily. The suffix "ju" is added to show respect. For example, "Baa-ju" means "father-in-law" where "ju" is added to "Baa(father)". Unlike "chaa", "ju" is not added to a first/last name directly. Instead, honorific terms like "Bhaaju" is added for males and "Mayju" for females. Example, "Birat bhaaju" for a male name (Birat) and "Suja Mayju" for a female name (Suja).

Prefix – "Tap'ah" is added to denote "remote" or "distant" relative ('distance' in relationship irrespective of spatial extent). A distant (younger) brother (kija) becomes "tap'ah-kija". "Tuh" is added to denote "higher". Father (baa)'s senior brother is referred to as "Tuh-baa".

Indo-Aryan loanwords

Newar is one of the most Aryanized Sino-Tibetan languages. Below are some basic words borrowed from Indo-Iranian languages:[83]

| Words | Origin (orig. word) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| La:h (ल:) | Pali (Jala:h) | Water |

| Kaa:sa | Pali | Bronze |

| Kaji | Arabic | leader |

| Khaapaa (खापा) | Pali | Door (Original meaning in Pali was "door panel") |

| Kimi (कीमी) | Sanskrit (Krmi) | Hookworm |

| Adha:vata | Persian | Malice |

| Ka:h | Pali (Kana) | Blind (Original meaning in Pali was "one-eyed") |

| Dya:h | Pali (Dev) | Deity |

| Nhya:h | Pali (Na:sika) | Nose |

| Mhu:tu | Pali (Mukhena) | Mouth |

| Khicha: (खिचा) | Pali (Kukkura) | Dog |

The Newar language and the Newar community

Nepal Bhasa is the native language of Newars. Newars form a very diverse community with people from Sino-Tibetan, ASI and ANI origin.[84] Newars follow Hinduism and Buddhism, and are subdivided into 64 castes. The language, therefore, plays a central unifying role in the existence and perpetuation of the Newar community. The poet Siddhidas Mahaju concluded that the Newar community and its rich culture can only survive if the Newar language survives (भाषा म्वासा जाति म्वाइ).

The Newars enjoyed promotions in various areas since Kathmandu become the capital of the country as they rose in ranks throughout the government, royal courts and businesses. However, the Newar language has languished as the state has patronized Gorkhali as the Nepali national language.

Newar faced a decline during the Shah era when this language was replaced by Khas Kura (later renamed Nepali) as the national language and after the introduction of the "One nation, one language" policy of King Mahendra. The then Royal Nepalese Government spent a lot for Sanskrit education and a Sanskrit University was approved during those times—although Sanskrit is virtually not spoken by anyone in Nepal—because Khas Kura's roots lie in Sanskrit. There were very few resources available then for even primary-level education in Newar. There were no programs broadcast in Newar on the state radio, Radio Nepal. Even after programs in Newar began to be broadcast, the language was referred to as "Newari", a term considered derogatory by Newars. Even today, there are no programs in Newar in the state television, Nepal Television, although it broadcasts a Bollywood Hindi movie every Saturday (although it is used as lingua franca in Terai, Hindi is the native language of less than 1% population in Nepal) and often Pakistani serials (in Urdu) as well. The Supreme Court of Nepal has also banned any use of Newar even for trivial matters in official purposes of any part of Nepal. These factors have led to a resentment among the Newar community.

This fact has been used for political advantages by many parties of Nepal. Many slogans are translated into Newar, although very few important documents of political parties are ever translated into Newar.

References

- Newar at Ethnologue (15th ed., 2005)

- Newar at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Middle Newar at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Subfamily: Newar". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Newar". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Genetti, Carol (2007). A Grammar of Dolakha Newar. Walter de Gruyter. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-11-019303-9.

Some people in Newar community, including some prominent Newar linguists, consider the derivational suffix -i found in the term Newari to constitute an 'Indianization' of the language name. These people thus hold the opinion that the term Newari is non-respectful of Newar culture.

- Maharjan, Resha (2018). The Journey of Nepal Bhasa: From Decline to Revitalization (M.Phil. thesis). UIT The Arctic University of Norway.

- Tumbahang, Govinda Bahadur (2010). "Marginalization of Indigenous Languages of Nepal" (PDF). Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 37 (1): 73–74. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Malla, Kamal P. "The Occupation of the Kathmandu Valley and its Fallout". p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Grandin, Ingemar. "Between the market and Comrade Mao: Newar cultural activism and ethnic/political movements (Nepal)". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Page 10.

- "Classical Newari Literature" (PDF). Retrieved 28 December 2011. Page 1.

- Thapa, Lekh Bahadur (1 November 2013). "Roots: A Khas story". The Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Hodgson, B. H. (1841). "Illustrations of the literature and religion of the Buddhists". Serampore. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 3.

- Clark, T. W. (1973). "Nepali and Pahari". Current Trends in Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 252.

- "The kings song". Himal Southasian. June 2003. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "It's Nepal Bhasa". The Rising Nepal. 9 September 1995.

- "Mass media directed to use Nepal Bhasa". The Rising Nepal. 14 November 1998.

- "Major highlights" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- Shrestha, Bal Gopal (2005). "Ritual and Identity in the Diaspora: The Newars in Sikkim" (PDF). Bulletin of Tibetology. Retrieved 21 March 2011. Page 26.

- "Himalaya Darpan". Himalaya Darpan. 20 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- "Newar". Ethnologue.

- Newari language and linguistic conspectus, CNAS,1981

- Mark Turin, Newar-Thangmi Linguistics Correspondence, Journal of Asian and African Studies, No. 68, 2004

- Tej R. Kansakar (June 1981). "Newari Language and Linguistics: Conspectus" (PDF). CNAS Journal. VIII (2). Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Mark Turin (12 September 2003). "Newar-Thangmi Lexical Correspondences and the Linguistic Classification of Thangmi" (PDF). Journal of Asian and African Studies. 68: 97. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- David N. Gellner (1986). Language, caste, religion and territory: Newar identity ancient and modern, European Journal of Sociology, p.102-148

- Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Pages 19-20.

- Malla, Kamal P. "The Earliest Dated Document in Newari: The Palmleaf from Uku Bahah NS 234/AD 1114". Kailash. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2012. Pages 15-25.

- Vajracarya, Dhanavajra and Malla, Kamal P. (1985) The Gopalarajavamsavali. Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Gutschow, Niels (1997). The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist Votive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. Edition Axel Menges. p. 25. ISBN 9783930698752. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- Bajracharya, Chunda (1985). Mallakalya Chhun Sanskriti ("Some Customs of the Malla Period"). Kathmandu: Kashinath Tamot for Nepal Bhasa Study and Research Centre.

- Pulangu Nepalbhasa Wangmaya-muna by Kashinath Tamot

- Mooldevshashidev by Jagatprakash Malla, edited by Saraswati Tuladhar

- Shrestha, Bal Gopal (January 1999). "The Newars: The Indigenous Population of the Kathmandu Valley in the Modern State of Nepal" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Levy, Robert I. (1990) Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-1038-4. Page 15.

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Pal, Pratapaditya (1985) Art of Nepal: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05407-3. Page 19.

- Singh, Phatte Bahadur (September 1979). "Nepali Biharya Aitihasik Pristabhumi ("Historical Background of Nepali Bihar")". Jaa. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Sahitya Pala, Tri-Chandra Campus. Page 186.

- Hutt, Michael (December 1986). "Diversity and Change in the Languages" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Tribhuvan University. Retrieved 20 March 2011. Page 10.

- Tumbahang, Govinda Bahadur (September 2009). "Process of Democratization and Linguistic (Human) Rights in Nepal". Tribhuvan University Journal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2011. Page 8.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 4.

- LeVine, Sarah and Gellner, David N. (2005). Rebuilding Buddhism: The Theravada Movement in Twentieth-Century Nepal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674019083, 9780674019089. Pages 47-49.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (1982, third ed.) Jheegu Sahitya ("Our Literature"). Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 8.

- Manandhar, T (7 March 2014). "Voice Of The People". The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Malla, Kamal P. "The Occupation of the Kathmandu Valley and its Fallout". p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Hoek, Bert van den & Shrestha, Balgopal (January 1995). "Education in the Mother Tongue: The Case of Nepal Bhasa (Newari)" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Retrieved 22 April 2012. Page 75.

- Shrestha, Bal Gopal (January 1999). "The Newars: The Indigenous Population of the Kathmandu Valley in the Modern State of Nepal)" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Gurung, Kishor (November–December 1993). "What is Nepali Music?" (PDF). Himal: 11. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- शुक्रराज अस्पताल स्मारिका २०५७, Page 52, नेपालभाषाको पुनर्जागरणमा शुक्रराज शास्त्री by सह-प्रा. प्रेमशान्ति तुलाधर

- Bajracharya, Phanindra Ratna (2003). Who's Who in Nepal Bhasha. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. Page 27.

- Sugata Saurabha: An Epic Poem from Nepal on the Life of the Buddha by Chittadhar Hridaya. Oxford Scholarship Online. 13 November 2009. ISBN 9780199866816. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Shrestha, Siddhicharan (1992). Siddhicharanya Nibandha ("Siddhicharan's Essays"). Kathmandu: Phalcha Pithana. Page 73.

- LeVine, Sarah and Gellner, David N. (2005). Rebuilding Buddhism: The Theravada Movement in Twentieth-Century Nepal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01908-3, ISBN 978-0-674-01908-9. Pages 47-49.

- Tewari, Ramesh Chandra (1983). "Socio-Cultural Aspects of Theravada Buddhism in Nepal". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. Retrieved 19 April 2012. Pages 89-90.

- Bajracharya, Phanindra Ratna (2003). Who's Who in Nepal Bhasha. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-560-0-X. Page 225.

- "History of Nepali Journalism". Nepal Press Institute. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Sandhya Times. 1 July 1997. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Whelpton, John (2005). A History of Nepal. Cambridge University Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780521804707. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Timalsina, Ramji (Spring 2011). "Language and Political Discourse in Nepal" (PDF). CET Journal. Itahari: Itahari Research Centre, Circle of English Teachers (CET). Retrieved 28 February 2012. Page 14.

- Hangen, Susan (2007). "Creating a "New Nepal": The Ethnic Dimension" (PDF). Washington: East-West Center. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Maharjan, Harsha Man (2009). "They' vs 'We': A Comparative Study on Representation of Adivasi Janajati Issues in Gorkhapatra and Nepal Bhasa Print Media in the Post Referendum Nepal (1979-1990)". Social Inclusion Research Fund. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012. Page 34.

- नेपालभाषाया न्हूगु पुलांगु म्ये मुना ब्वः१

- Eagle, Sonia (1999). "The Language Situation in Nepal". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Scribd. Retrieved 28 February 2012. Page 310.

- "Constitution of Nepal 1990". Nepal Democracy. 2001. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Limbu, Ramyata (21 June 1999). "Attempt to Limit Official Language to Nepali Resented". IPS. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "The Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2063 (2007)" (PDF). UNDP Nepal. January 2009. p. 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- "State affairs". The Kathmandu Post. 7 July 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Jigu Nan Dhayegu Du". Sandhya Times. 18 July 2013. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Nepal Bhasa Wikipedia". new.wikipedia.org.

- Rai, Ganesh (11 April 2012). "९७ विद्यालयमा नेपालभाषा पढाइने ("Nepal Bhasa to be taught in 97 schools")". Kantipur. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 113.

- Jhee (February–March 1975). Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Bikas Mandal. Page 9.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Pages 255-256.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 47.

- Kansakar, Tej R. 2011. A sociolinguistic survey of Newar / Nepal Bhasa. Linguistic Survey of Nepal (LinSuN), Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Genetti, Carol (2003). Dolakhā Newār. The Sino-Tibetan Languages: London & New York: Routledge. pp. 353–370.

- Hargreaves, David (2003). Kathmandu Newar (Nepāl Bhāśā). The Sino-Tibetan Languages: London & New York: Routledge. pp. 371–384.

- Hale, Austin; Shrestha, Kedar P. (2006). Newār (Nepāl Bhāsā). Languages of the World/Materials, 256: München: LINCOM. pp. 1–22.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Page 14.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 2.

- Nepal Bhasa Wyaakarana (page 2) by Tuyubahadur Maharjan, published by Nepal Bhasa Academy

- From the review article on "Dictionary of classical Newari compiled from manuscript sources." With the financial support of Toyota Foundation, Japan, Nepal Bhasa Dictionary Committee. Cwasā Pāsā. Kathmandu: Modern Printing Press, Jamal 2000, pp. XXXV, 530. ISBN 99933-31-60-0"

- Metspalu, Mait (December 2011). "Shared and Unique Components of Human Population Structure and Genome-Wide Signals of Positive Selection in South Asia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (6): 731–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010. PMC 3234374. PMID 22152676.

Further reading

- Bendix, E. (1974) ‘Indo-Aryan and Tibeto-Burman contact as seen through Nepali and Newari verb tenses’, International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 3.1: 42–59.

- —— (1992) ‘The grammaticalization of responsibility and evidence: the interactional potential of evidential categories in Newari’, in J. Hill and J.T. Irvine (eds) Responsibility and Evidence in Oral Discourse, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Driem, G. van (1993) ‘The Newar verb in Tibeto-Burman perspective’, Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 26: 23–43.

- Genetti, C. (1988) ‘A syntactic correlate of topicality in Newari narrative’, in S. Thompson and J. Haiman (eds) Clause Combining in Grammar and Discourse, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- —— (1994) ‘A descriptive and historical account of the Dolakha Newari dialect’, Monumenta Serindica 24, Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Hale, A. (1973) ‘On the form of the verbal basis in Newari’, in Braj Kachru et al. (eds) Issues in Linguistics: Papers in Honor of Henry and Renee Kahane, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- —— (1980) ‘Person markers: finite conjunct and disjunct forms in Newari’, in R. Trail (ed.) Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics 7 (Pacific Linguistics Series A, no. 53), Canberra: Australian National University.

- —— (1985) ‘Noun phrase form and cohesive function in Newari’, in U. Piepel and G. Stickel (eds.) Studia Linguistica Diachronica et Synchronica, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- —— (1986) ‘Users’ guide to the Newari dictionary’, in T. Manandhar (ed.) Newari–English Dictionary, Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

- —— (1994) ‘Entailed kin reference and Newari -mha’, paper presented to the 27th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Paris, France.

- Hale, A. and Mahandhar, T. (1980) ‘Case and role in Newari’, in R. Trail (ed.) Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics 7 (Pacific Linguistics Series A, no. 53), Canberra: Australian National University.

- Hargreaves, D. (1986) ‘Independent verbs and auxiliary functions in Newari’ Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 12: 401–12.

- —— (1991) ‘The conceptual structure of intentional action: data from Kathmandu Newari’, Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 17: 379–89.

- —— (1996) ‘From interrogation to topicalization: PTB *la in Kathmandu Newar’, Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 19.2: 31–44.

- Jørgenson, H. (1931) ‘A dictionary of the Classical Newari’, Det. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser 23.1.

- —— (1941) ‘A grammar of the Classical Newari’, Det. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser 27.3.

- Jos/, L.K. (1992) [NS 1112] ‘Nep%l bh%M%y% bh%M%vaijñ%nika vyakaraNa’ (A linguistic grammar of

nep%l bh%Ma (Newar)), Kathmandu: Lacoul Publications.

- Kansakar, T.R. (1982) ‘Morphophonemics of the Newari verb’, in T.R. Kansakar (ed.) Occasional Papers in Nepalese Linguistics 12–29. Linguistic Society of Nepal Publication No.1, Lalitpur, Nepal.

- —— (1997) ‘The Newar language: a profile’, New%h Vijñ%na: Journal of Newar Studies 1.1: 11–28.

- Kölver, U. (1976) ‘Satztypen und verbsubcategorisierung der Newari’, Structura 10, Munich: Fink Verlag.

- —— (1977) ‘Nominalization and lexicalization in Newari’, Arbeiten des Kölner Universalen-Projekts 30.

- Kölver, U. and Shresthacarya, I. (1994) A Dictionary of Contemporary Newari, Bonn: VGH Wissenschaftsverlag.

Manandhar, T. (1986) Newari-English Dictionary, Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

- Malla, K.P. (1982) Classical Newari Literature: A Sketch, Kathmandu: Educational Enterprise Pvt. Ltd.

- —— (1985) ‘The Newari language: a working outline’, Monumenta Serindica No. 14., Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Shakya, D.R. (1992) ‘Nominal and verbal morphology in six dialects of Newari’, unpublished masters thesis, University of Oregon.

- Shrestha, Uma (1990) ‘Social networks and code-switching in the Newar community of Kathmandu City’, unpublished PhD dissertation, Ball State University.

- Shresthacharya, I. (1976) ‘Some types of reduplication in the Newari verb phrase’, Contributions

to Nepalese Studies 3.1: 117–27.

- —— (1981) ‘Newari root verbs’, Bibliotheca Himalayica 2.1, Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

External links

| Newari edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Nepal Bhasa |