Nepal Sambat

Nepal Sambat (Nepalese: नेपाल सम्बत) is the lunar calendar used by the Nepalese-speaking people native to the Indian subcontinent of Nepalese nationality and ethnic Nepalis.[1] The Calendar era began on 20 October 879 AD, with 1140 in Nepal Sambat corresponding to the year 2019–2020 AD. Nepal Sambat appeared on coins, stone and copper plate inscriptions, royal decrees, chronicles, Hindu and Buddhist manuscripts, legal documents and correspondence.[2] Though Nepal Sambat is declared a national calendar, it is used widely in Nepal. It is mostly used by the newar community whereas Bikram Sambat (B.S) remains the dominant calendar throughout the country. All the major festivals are based on Bikram Sambat along with official purposes.

History

The name Nepal Sambat was used for the calendar for the first time in Nepal Sambat 148 (1028 AD).[3]

Sankhadhar Sakhwa

The Nepal Sambat epoch corresponds to 879 AD, which commemorates the payment of all the debts of the Nepalese people by a merchant named Sankhadhar Sakhwa in popular legend.[4][5] According to the legend, an astrologer from Bhaktapur predicted that the sand at the confluence Bhacha Khushi and Bishnumati River in Kathmandu would transform into gold at a certain moment, so the king sent a team of workers to Kathmandu to collect sand from the spot at the special hour. A local merchant named Sankhadhar Sakhwa saw them resting with their baskets of sand at a traveler's shelter at Maru near Durbar Square before returning to Bhaktapur. Believing that the sand to be unusual if the workers were gathering it, he convinced them to give it to him instead. The next day, Sakhwa discovered his sand had turned to gold, while the king of Bhaktapur was left with a pile of ordinary sand which his porters had dug up after the auspicious hour had passed. Sankhadhar used the gold to repay the debts of the Nepalese people.[6][7]

Use outside Kathmandu

Nepal Sambat has also been used outside Nepal Mandala in Nepal and in other countries including India, China and Myanmar. In Gorkha, a stone inscription at the Bhairav Temple at Pokharithok Bazaar contains the date Nepal Sambat 704 (1584 AD). An inscription in the Khas language at a rest house in Salyankot is dated Nepal Sambat 912 (1792 AD).[8] In east Nepal, an inscription on the Bidyadhari Ajima Temple in Bhojpur recording the donation of a door and tympanum is dated Nepal Sambat 1011 (1891 AD). The Bindhyabasini Temple in Bandipur in west Nepal contains an inscription dated Nepal Sambat 950 (1830 AD) recording the donation of a tympanum.[9] The Palanchok Bhagawati Temple situated to the east of Kathmandu contains an inscription recording a land donation dated Nepal Sambat 861 (1741 AD).[10] An inscription on a stupa in Panauti is dated Nepal Sambat 866 (1746 AD).[11]

Similarly, Nepalese merchants based in Tibet (Lhasa Newars) used Nepal Sambat in their official documents, correspondence and inscriptions recording votive offerings.[12] A copper plate recording the donation of a tympanum at the shrine of Chhwaskamini Ajima (Tibetan: Palden Lhamo) in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa is dated Nepal Sambat 781 (1661 AD).[13]

Suppression and campaign for revival

Nepal Sambat was replaced as the national calendar in Rana period of the Kingdom of Nepal. The victory of the Gorkha Kingdom resulted in the end of the Malla dynasty and the advent of The Shahs used Saka era. However, Nepal Sambat remained in official use for a time even after the coming of the Shahs. For example, the treaty with Tibet signed during the reign of Pratap Singh Shah is dated Nepal Sambat 895 (1775 AD). In 1903, Saka Sambat, in turn, was superseded by Bikram Sambat as the official calendar.[14] However, the government continued to use Saka Sambat on gold and silver coins till 1912 when it was fully replaced by Bikram Sambat.[15][16]

The campaign to reinstate Nepal Sambat as the national calendar began in the 1920s when Dharmaditya Dharmacharya, a Buddhist and Nepal Bhasa activist based in Kolkata, initiated a campaign to promote it as the national calendar. The movement was continued by language and cultural activists in Nepal with the advent of democracy following the ouster of the autocratic Rana dynasty in 1951.[17] The demand to make Nepal Sambat a national calendar intensified with the establishment of Nepal Bhasa Manka Khala in 1979. It organized rallies and public functions publicizing the importance of the era as a symbol of nationalism. Nepal Sambat has also emerged as a symbol to rally people against the suppression of their culture, language and literature by the politically dominant ruling classes.[18] The Panchayat regime suppressed the movement by arresting and imprisoning the activists.[19][20] In 1987 in Kathmandu, a road running event organized to mark the New Year was broken up by police and the runners thrown in jail.[21]

Reinstated as national calendar

The Nepal Sambat movement achieved its first success on 18 November 1999 when the government declared the founder of the calendar, a trader of Kathmandu named Sankhadhar Sakhwa (संखधर साख्वा), a national hero.[22] On 26 October 2003, the Department of Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp depicting his portrait.[23] A statue of Sankhadhar was erected in Tansen, Palpa in western Nepal on 28 January 2012.[24]

On 25 October 2011, the government decided to bring Nepal Sambat into use as the country's national calendar following prolonged lobbying by cultural and social organizations, most prominently by Nepal Bhasa Manka Khala,[25] and formed a taskforce to make recommendations on its implementation.[26] All major newspapers now print Nepal Sambat along with other dates on their mastheads. New Year's Day celebrations have also spread from the Kathmandu Valley to other towns in Nepal as well as abroad.[27]

Structure

Months of the year

| Devanagari script | Roman script | Corresponding Gregorian month | Name of Full Moon |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. कछला | Kachhalā | November | Saki Milā Punhi, Kārtik Purnimā |

| 2. थिंला | Thinlā | December | Yomari Punhi, Dhānya Purnimā |

| 3. पोहेला | Pohelā | January | Milā Punhi, Paush Purnimā |

| 4. सिल्ला | Sillā | February | Si Punhi, Māghi Purnimā |

| 5. चिल्ला | Chillā | March | Holi Punhi, Phāgu Purnimā |

| 6. चौला | Chaulā | April | Lhuti Punhi, Bālāju Purnimā |

| 7. बछला | Bachhalā | May | Swānyā Punhi, Baisākh Purnimā |

| 8. तछला | Tachhalā | June | Jyā Punhi, Gaidu Purnimā |

| 9. दिल्ला | Dillā | July | Dillā Punhi, Guru Purnimā |

| 10. गुंला | Gunlā | August | Gun Punhi, Janāi Purnimā (Raksha Bandhan) |

| 11. ञला | Yanlā | September | Yenyā Punhi, Bhādra Purnimā |

| 12. कौला | Kaulā | October | Katin Punhi, Kojāgrat Purnimā |

Nepal Sambat is a lunisolar calendar with 354 days in a normal year. An intercalary month named Anālā (अनाला) is added every three years to prevent the calendar from drifting with the seasons.[28]

New Year

New Year's Day falls on the first day of the waxing moon during the Swanti festival.[29] Traditionally, traders used to close their ledgers and open new account books on the first day of Nepal Sambat. Newars observe New Year's Day by performing Mha Puja (Nepal Bhasa: म्हपुजा), a ritual to purify and empower the soul for the coming New Year besides praying for longevity.[30] During this ceremony, family members sit cross-legged in a row on the floor in front of mandalas (sand paintings) drawn for each person. Offerings are made to the mandala, and each family member is presented auspicious ritual food which includes boiled egg, smoked fish and rice wine during the Sagan ceremony. Mha Puja and Nepal Sambat are also celebrated abroad where Nepalese have settled.[31]

Outdoor celebrations of the new year consist of cultural processions, pageants, and rallies. Participants dressed in traditional Newar clothing like tapālan, suruwā and hāku patāsi parade on the streets. Musical bands playing various kinds of drums take part in the processions. Streets and market squares are decorated with arches, gates, and banners bearing new year greetings. The president of Nepal also issues a message of greetings on the occasion of New Year's Day.[32] Public functions are held in which the prime minister and other government leaders participate. Marking a break from tradition, Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai gave his speech at the New Year's Day program in 2011 in Nepal Bhasa.[33]

Milestones

888 Nepal Sambat (1768 CE) - Prithvi Narayan Shah's Gorkhali forces take Kathmandu.

926 (1806) - Bhandarkhal Massacre establishes Bhimsen Thapa as the prime minister of Nepal.

966 (1846) - Kot massacre establishes Jang Bahadur Rana as the prime minister of Nepal and the Rana dynasty.

1054 (1934) - Great Earthquake strikes Nepal.

1061 (1941) - Four martyrs executed by the Rana regime.

1071 (1951) - Revolution topples Rana regime and establishes democracy.

1080 (1960) - Parliamentary system abolished and Panchayat system established.

1111 (1991) - First parliamentary election held after abolition of Panchayat and reinstatement of democracy.

1121 (2001) - The king, queen and other members of the royal family are killed in Nepalese royal massacre.

1128 (2008) - Nepal becomes a republic.[34]

Gallery

- Coin issued in the name of King Ranjit Malla dated Nepal Era 842 (1722 CE)

- Coin issued in the name of King Prithvi Narayan Shah dated Saka Era 1685 (1763 CE)

- Coin issued in the name of King Surendra Bikram Shah dated 1788 Saka Era (1866 CE)

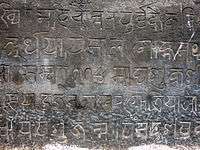

King Pratap Malla's inscription at Durbar Square dated Nepal Era 774 (1654 CE)

King Pratap Malla's inscription at Durbar Square dated Nepal Era 774 (1654 CE) Sanskrit Buddhist manuscript dated Nepal Era 989 (1869 CE)

Sanskrit Buddhist manuscript dated Nepal Era 989 (1869 CE) Copper plate inscription dated Nepal Era 1072 (1952 CE)

Copper plate inscription dated Nepal Era 1072 (1952 CE)

References

- Bernardo A. Michael (1 October 2014). Statemaking and Territory in South Asia: Lessons from the Anglo–Gorkha War (1814–1816). Anthem Press. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-1-78308-322-0.

- Gurung, D. B. (2003) Nepal tomorrow: voices & visions. Koselee Prakashan. ISBN 99933-671-0-9, ISBN 978-99933-671-0-9. Page 661.

- Malla, K. P. (1982). "The Relevance of Nepala Samvat". Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2012. Page 1.

- https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/sankhadhar-sakhwa-may-never-existed-experts/

- "My Republica". Archived from the original on 2016-01-05. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- Pradhananga, Gyanendra Dhar (29 January 2012). "The sands of time". The Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Wright, Daniel (1990). History of Nepal. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 163–165. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Itihas Prakash (14 April 1955). Kathmandu: Itihas Prakash Mandal. Page 37.

- Jhee (February–March 1975). Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Bikas Mandal. Page 9.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Pages 113.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Pages 114.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Pages 255-256.

- Hridaya, Chittadhar (ed.) (1971). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Jatah. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 47.

- "My Republica". Archived from the original on 2016-01-05. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- Pradhan, Bhuvan Lal (1995). "Maniharsha Jyoti in the Fields of Religion, Language and Era". In Memory of Maniharsha Jyoti. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 460.

- Money, George Wigram Pocklington. (1917) Gurkhali Manual. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1576-X, 9788120615762. Page 32.

- Xinhua (27 October 2011). "Nepal Sambat 1132 being celebrated in Nepal". China Daily. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- Malla, K. P. (1982). "The Relevance of Nepala Samvat". Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2012. Page 5.

- Sayami, Sneha (28 February – 13 March 2004). "Swayatta Newa Chhalphal Garna Sakinchha" [Newar autonomy can be discussed]. Himal Khabarpatrika (in Nepali). Lalitpur: Himalmedia. p. 35.

- "Nepal Sambat will have no adverse impact". The Rising Nepal. 2008. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- Tuladhar, Kamal (4 January 1991). "Culture clubbed". The Rising Nepal - Friday Supplement.

- Joshi, Amar Prasad (2008). "Shankhadhar Sakhwa: Founder of Nepal Samvat". The Rising Nepal. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- "NP010.03". Universal Postal Union. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- Sandhya Times (29 January 2012). Kathmandu: Artha Pithana Prakashan. Page 1.

- Pradhananga, Gyanendra Dhar (29 January 2012). "The sands of time". The Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Govt to bring Nepal Sambat into use". Republica. 25 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Nepal Sambat 1131". Newah Organization of America. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Levy, Robert Isaac (1990). "A Catalogue of Annual Events and Their Distribution throughout the Lunar Year". Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal. University of California Press. pp. 643–657. ISBN 9780520069114.

- Wright, Daniel (1990). History of Nepal. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 34. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Mha Puja today, Nepal Sambat 1132 being observed". Ekantipur. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Mha Puja 2012 & New Year Nepal Samvat 1133 Celebration". Pasa Puchah Guthi UK. 2012. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "Prez‚ Chairman extend Nepal Sambat New Year greetings". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- "PM Bhattarai addresses programme marking Nepal Sambat 1132 in Nepal Bhasa". Nepalnews.com. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- "Nepal profile". BBC. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.