Nyungar language

Nyungar (/ˈnjʊŋɡər/; also Noongar) is an Australian Aboriginal language or dialect continuum, still spoken by members of the Noongar community, who live in the southwest corner of Western Australia. The 1996 census recorded 157 speakers; that number increased to 232 by 2006. The rigour of the data collection by the Australian Bureau of Statistics census data has been challenged, with the number of speakers believed to be considerably higher.[4]

| Nyungar | |

|---|---|

| Noongar | |

| Region | Western Australia |

| Ethnicity | Noongar (Amangu, Ballardong, Yued, Kaneang, Koreng, Mineng, ?Njakinjaki, Njunga, Pibelmen, Pindjarup, Wardandi, Whadjuk, Wiilman, Wudjari) |

Native speakers | 475 (2016 census)[1] |

Pama–Nyungan

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | nys – inclusive codeIndividual codes: xgg – Gorengxrg – Minang (Mirnong)xbp – Bibbulman (Pipelman)wxw – Wardandipnj – Pinjarupxwj – Wajuk (Whadjuk) |

qsz Juat (Yuat) | |

| Glottolog | nyun1247[2] |

| AIATSIS[3] | W41 |

Noongar was first recorded in 1801 by Matthew Flinders, who made a number of word lists.[5]

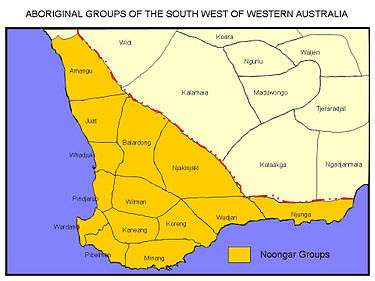

Dialects/languages of the Nyungar subgroup

It is generally agreed that there was no single, standard Nyungar (or Noongar) language before European settlement: it was a subgroup (or possibly a dialect continuum) of closely related languages, whose speakers were differentiated geographically (and in some cases, by cultural practices). The dialects merged into the modern Nyungar language following colonisation. A 1990 conference organised by the Nyoongar Language Project Advisory Panel recognised that the Nyungar subgroup included at least three distinct languages. This was highlighted by a 2011 Noongar Dictionary, edited by Bernard Rooney, which was based on the dialect/language of Yuat (Juat), from the north west part of the Nyungar subgroup area.[6]

The highlighted area of the map shown on the right may correspond to the Nyungar subgroup. The subdivisions shown correspond to individual dialects/languages. In modern Nyungar these dialects/languages have merged. There is controversy in some cases as to whether all of these dialects/languages were part of the original Nyungar subgroup. Some may have been distinct languages and some may have belonged to neighbouring subgroups.

Many linguists believe that the northernmost language shown, Amangu, was not part of the Nyungar subgroup, was instead a part of the Kartu subgroup, and may have been a dialect of the Kartu language Nhanda. (As such, Amangu may have been synonymous with a dialect known as Nhanhagardi, which has also been classified, at different times, as a part of Nhanda, Nyungar, or Widi.)

There is a general consensus that the following dialects/languages belong to the Nyungar subgroup:[3] Wudjari, Minang, Bibelman (a.k.a. Pibelman; Bibbulman),[7] Kaneang (Kaniyang), Wardandi, Balardung (a.k.a. Ballardong; which probably included Tjapanmay/Djabanmai), and Yuat (Juat).

Wiilman, Whadjuk (Wajuk) and Pinjarup are also usually regarded as dialects of Nyungar, although this identification is not completely secure.

The Koreng (Goreng) people are thought to have spoken a dialect of, or closely related to, Wudjari, in which case their language would have been part of the Nyungar subgroup.

Njakinjaki (Nyakinyaki) was possibly a dialect of Kalaamaya – a language related to, but separate from, the original Nyungar subgroup.[7]

It is not clear if the Njunga (or Nunga) dialect was significantly different from Wudjari. However, according to Norman Tindale, the Njunga people rejected the name Wudjari and had adopted some of the customs of their non-Nyungar-speaking eastern neighbours, the Ngadjunmaya.[8]

Documentation

The Nyungar names for birds were included in Serventy and Whittell's Birds of Western Australia (1948), noting their regional variations.[9] A later review and synthesis of recorded names and consultation with Nyungars produced a list of recommended orthography and pronunciation for birds (2009) occurring in the region.[9] The author, Ian Abbott, also published these recommendations for plants (1983) and mammals (2001), and proposed that these replace other vernacular in common use.[10]

A number of small wordlists were recorded in the early days of the Swan River Colony, for example Robert Menli Lyon's 1833 publication A Glance at the Manners and Language of Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia. Lyon acquired much of his information from Yagan while Yagan was incarcerated on Carnac Island. Despite the significance of Lyons work in being the first of its kind, George Fletcher Moore diary republished in 1884 described Lyons work as "containing many inaccuracies and much that was fanciful".[11] During August and October 1839 the Perth Gazette published Vocabulary of the Aboriginal people of Western Australia written by Lieutenant Grey of HM 83rd Regiment.[12][13] Grey spent twelve months studying the languages of the Nyungar people and came to the conclusion that there was much in common between them, just prior to the publication he received from Mr Bussel of the Busselton district a list of 320 words from that region which was near identical to those he had collected in the Swan River region. The work of Grey much to his disappointment was published in an unfinished list as he was leaving the colony, but he believed that the publication would assist in communication between settlers and Nyungar people. Also noted by Grey was that the Nyungar language had no soft c sound, there was no use of f and that h was very rarely used and never at the start of a word.[14]

Serious documentation of the Nyungar language began in 1842 with the publication of A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia by George Fletcher Moore, later republished in 1884 as part of the diary of George Fletcher Moore. This work included a substantial wordlist of Nyungar. The first modern linguistic research on Nyungar was carried out by Gerhardt Laves on the variety known as "Goreng", near Albany in 1930, but this material was lost for many years and has only recently been recovered. Beginning in the 1930s and then more intensively in the 1960s Wilfrid Douglas learnt and studied Nyungar, eventually producing a grammar, dictionary, and other materials.[15] More recently Nyungar people have taken a major role in this work as researchers, for example Rose Whitehurst who compiled the Noongar Dictionary in her work for the Noongar Language and Culture Centre.[16] Tim McCabe has recently finished a PhD in the Nyungar language, having been taught a variety of the language by Clive Humphreys of Kellerberrin, and is teaching Nyungar to inmates in Perth prisons.

Peter Bindon and Ross Chadwick have compiled an authoritative cross referenced "A Nyoongar Wordlist: from the South West of Western Australia", by assembling material from all of the above writers in their original spelling. It is clear from this reference that the orthographies used did not only reflect dialectical differences, but also how the various authors "heard" and transcribed spoken Nyungar.[17]

Current situation

| Neo-Nyungar | |

|---|---|

| Region | SW Australia |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 8,000)[18] |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

eng-neo | |

| Glottolog | None |

Today the Nyungar language is disputed as being endangered; there has been a revival of interest in recent years, and Professor Len Collard from the Indigenous Studies faculty at the University of Western Australia has challenged the science behind the claim, citing the lack of rigour in the data.[4] The Noongar Language and Culture Centre was set up by concerned individuals and has now grown to include offices in Bunbury, Northam and Perth. Authors such as Charmaine Bennell have released several books in the language.[19] Educators Glenys Collard and Rose Whitehurst started recording elders speaking using Noongar language in 1990, and by 2010 had 37 schools in the South West and Perth teaching the language.[20]

An English dialect with Nyungar admixture, known as Neo-Nyungar, is spoken by perhaps 8,000 ethnic Nyungar.[21]

Recently, the collaborative work of digitising and transcribing many word lists created by ethnographer Daisy Bates the 1900s at Daisy Bates Online[22] provides a valuable resource for those researching especially Western Australian languages.[23] The project is co-ordinated by Nick Thieburger, who works in collaboration with the National Library of Australia "to have all the microfilmed images from Section XII of the Bates papers digitised", and the project is ongoing.[24]

Language through the arts

Singer-songwriter Gina Williams has promoted the use of the language through song, including lullabies for children and a translation of the song "Moon River".[25]

An adaption and translation of the Shakespearean tragedy Macbeth into Nyungar is on the programme for the 2020 Perth Festival. The play, named Hecate, is produced by Yirra Yaakin Theatre Company with Bell Shakespeare, and performed by an all-Noongar cast. The play took years to translate, and has sparked wider interest in reviving the language.[25][26]

Phonology

The following are the sounds in the Noongar language:[16]

Vocabulary

Many words vary in a regular way from dialect to dialect, depending on the area. For example: the words for bandicoot include quernt (south) and quenda (west); the word for water may be käip (south) or kapi (west), or the word for fire may vary from kaall to karl.

A large number of modern place names in Western Australia end in -up, such as Joondalup, Nannup and Manjimup. This is because in the Noongar language, -up means "place of". For example, the name Ongerup means "place of the male kangaroo".[27] The word "gur", "ger" or "ker" in Noongar meant a gathering. Daisy Bates suggests that central to Noongar culture was the "karlupgur", referring to those that gather around the hearth (karlup).[28]

Nyungar words which have been adopted into Western Australian English, or more widely in English, include the given name Kylie "boomerang",[29] gilgie or jilgie, the freshwater crayfish Cherax quinquecarinatus, and gidgie or gidgee, "spear". The word for smoke, karrik, was adopted for the family of compounds known as karrikins. The word kodj "to be hit on the head" comes from the term for a stone axe.[29] The word quokka, denoting a type of small macropod, is thought to come from Nyungar.[30]

Pronunciation

| Letter | English sound | Nyunga sound |

|---|---|---|

| B | book | boodjar |

| D | dog | darbal |

| dj or tj | dew | djen or nortj |

| ny | canyon | nyungar |

| ng | sing | ngow |

Grammar

Nyungar grammar is fairly typical of Pama–Nyungan languages in that it is agglutinating, with words and phrases formed by the addition of affixes to verb and noun stems.[31] Word order in Nyungar is free, but generally tends to follow a subject–object–verb pattern.[32] Because there are several varieties of Nyungar,[33] aspects of grammar, syntax and orthography are highly regionally variable.

Verbs

Like most Australian languages, Nyungar has a complex tense and aspect system.[34] The plain verb stem functions as both the infinitive and the present tense. Verb phrases are formed by adding suffixes or adverbs to the verb stem.[35]

The following adverbs are used to indicate grammatical tense or aspect.[36][37]

- boorda later (boorda ngaarn, “will eat later”)

- mila future (mila ngaarn, “will eat after a while”)

- doora conditional (doora ngaarn, “should eat”)

Some tense/aspect distinctions are indicated by use of a verb suffix. In Nyungar, the past or preterite tense is the same as the past participle.[36]

- -iny progressive (ngaarniny, “eating”)

- -ga past (ngaarnga, “ate, had eaten”)

A few adverbs are used with the past tense to indicate the amount of time since the event of the verb took place.[36]

- gorah a long time (gorah gaarnga, “ate a long time ago”)

- karamb a short time (karamb ngaarnga, “ate a little while ago”)

- gori just now (gori ngaarnga, “just ate”)

Nouns

There are no articles in Nyungar.[38][39] Nouns (as well as adjectives) take a variety of suffixes which indicate grammatical case, specifically relating to motion or direction, among other distinctions.[40][41]

- -(a)k locative (boorn-ak, “in the tree”)

- -(a)k purposive (daatj-ak, “for meat”)

- -(a)l instrumental (kitj-al, “by means of a spear”)

- -an/ang genitive (noon-an kabarli, “your grandmother”)

- -(a)p place-of (boorn-ap, “place of trees”)

- -koorl illative (keba-koorl, “towards the water”)

- -ool ablative (kep-ool, “away from the water”)

- -ngat adessive (keba-ngat, “near the water”)

- -(a)biny translative (moorditj-abiny, “becoming strong”)

- -mokiny semblative (dwert-mokiny, “like a dog”)

- -boorong having or existing (moorn-boorong, “getting dark”)

- -broo abessive (bwoka-broo, “without a coat”)

- -kadak comitative (mereny-kadak, “with food”)

- -mit used-for (kitjal baal daatj-mit barangin'y, “a spear is used for hunting kangaroos”)

- -koop belong-to, inhabitant of (bilya-koop, “river dweller”)

- -djil emphatic (kwaba-djil, “very good”)

- -mart species or family (bwardong-mart, “crow species”)

- -(i)l agentive suffix used with ergative

The direct object of a sentence (what might be called the Dative) can also be expressed with the locative suffix -ak.[42][43]

Grammatical number is likewise expressed by the addition of suffixes. Nouns that end in vowels take the plural suffix -man, whereas nouns that end in consonants take -gar.[44][45] Inanimate nouns, that is, nouns that do not denote human beings, can also be pluralized by the simple addition of a numeral.[45]

Pronouns

Nyungar pronouns are declined exactly as nouns, taking the same endings.[43][46] Thus, possessive pronouns are formed by the addition of the regular genitive suffix -ang.[46] Conversely, object pronouns are formed by the addition of the -any suffix.[46] Notably, there does not appear to be a great deal of pronominal variation across dialectal lines.[44]

Subject Object Possessive I ngany nganyany nganyang he/she/it baal baalany baalang they baalap baalabany baalabang you noonook noonany noonang we ngalak ngalany ngalang

Nyungar features a set of dual number pronouns which identify interpersonal relationships based on kinship or marriage. The “fraternal” dual pronouns are used by and for people who are siblings or close friends, “paternal” dual pronouns are used by and for people who are paternal relatives (parent-child, uncle-niece and so forth),[47] and “marital” pronouns are used by and for people who are married to each other or are in-laws.[48]

Fraternal Paternal Marital 1st person ngali ngala nganik 2nd person nubal nubal nubin 3rd person bula bulala bulen

Typically, if the subject of a sentence is not qualified by a numeral or adjective, a subject-marker pronoun is used. Thus: yongka baal boyak yaakiny (lit. “kangaroo it on-rock standing), “the kangaroo is standing on the rock.”[49]

Adjectives

Adjectives precede nouns.[49] Some adjectives form the comparative by addition of the suffix -jin but more generally the comparative is formed by reduplication, a common feature in Pama-Nyungan languages.[50] The same is also true for intensified or emphatic adjectives, comparable to the English word “very”. The superlative is formed by the addition of -jil.[51]

Negation

Statements are negated by adding the appropriate particle to the end of the sentence. There are three negation particles:

- bart used generally with verbs

- yuada used generally with adjectives

There is also an adverbial negation word, bru, roughly equivalent to the English “less” or “without”.[52]

Interrogatives

Questions are formed by the addition of the interrogative interjection kannah alongside the infinitive root of the verb.[53]

See also

References

- "Census 2016, Language spoken at home by Sex (SA2+)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Nyunga". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- W41 Nyungar at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Collard, Len. "Noongarpedia". RTRFM. RTRFM. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- "Language | Kaartdijin Noongar". www.noongarculture.org.au. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Rooney, Bernard (2011). Nyoongar dictionary. Batchelor Press. ISBN 9781741312331.

- Spelling may vary, especially in the case of "Bilelman" and "Nadji Nadji", which are apparent errors for Bibbulman and Njakinjaki.

- "Njunga (WA)"

- Abbott, Ian (2009). "Aboriginal names of bird species in south-west Western Australia, with suggestions for their adoption into common usage" (PDF). Conservation Science Western Australia Journal. 7 (2): 213–78 [255].

- Abbott, Ian (2001). "Aboriginal names of mammal species in south-west Western Australia". CALMScience. 3 (4): 433–486.

- Bindon, Peter; Ross, Chadwick (2011). Nyoongar Wordlist (second ed.). Welshpool WA: Western Australian Museum. ISBN 9781920843595.

- "Grey, Sir George (1812–1898)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- Grey, George (1839). – via Wikisource.

- "VOCABULARY OF THE ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA". The Perth Gazette And Western Australian Journal. VII (346). Western Australia. 24 August 1839. p. 135. Retrieved 22 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Douglas, W. (1996) Illustrated dictionary of the South-West Aboriginal language Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Whitehurst, R. (1997) Noongar Dictionary Noongar to English and English to Noongar (2nd Ed) Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Bindon, Peter and Chadwick, Ross (2011), "A Nyoongar Wordlist: from the South West of Western Australia" (WA Museum books)

- Nyunga at Ethnologue (8th ed., 1974). Note: Data may come from an earlier edition.

- "Western and Northern Aboriginal Language Alliance Conference - List of Authors". Batchelor Press. 2013. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- Sharon Kennedy (20 July 2010). "Learning Noongar language". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Nyunga at Ethnologue (12th ed., 1992).

- "Digital Daisy Bates". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Map". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Technical details". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Turner, Rebecca (25 January 2020). "Noongar language reborn in Hecate, an Aboriginal translation of Shakespeare's Macbeth at Perth Festival". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Shakespeare in Noongar a world first" (PDF). Perth Festival. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Place of the Male Kangaroo" Albany GateWAy Co-operative Limited, 28 July 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- Bates, Daisy (1937), "The Passing of the Aborigines"

- "A Noongar word for 'smoke' finds a place in science". University of Western Australia News. 6 March 2009.

- Oxford Dictionary of English, p 1,459.

- Baker, Brett (2014). "Word Structure in Australian Languages". In Koch, Harold and Rachel Nordlinger. The Languages and Linguistics of Australia. De Gruyter. p.164.

- Spehn-Jackson, Lois (2015). Noongar Waangkiny: A Learner’s Guide to Noongar. Batchelor Press. p.12.

- Bates, Daisy M (1914). “A Few Notes on Some South-Western Australian Dialects.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 44.6 pp.77.

- Stirling, Lesley and Alan Dench. “Tense, Aspect, Modality and Evidentiality in Australian Languages: Foreword.” Australian Journal of Linguistics 32.1 (2012): 3

- Symmons, Charles (1842) “Grammatical Introduction to the Study of the Aboriginal Language of Western Australia.” Western Australia Almanack. p.xvii.

- Symmons 1842, p.xvii.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.16.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.11.

- Bates 1914, p.66.

- Symmons 1842, p.viii.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.18-19.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.18.

- Symmons 1842, p.xiii.

- Bates 1914, p.68.

- Symmons 1842, p.ix.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.20.

- Symmons 1842, p.xiv.

- Symmons 1842, p.xv.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.13.

- Baker 2014, p.182.

- Symmons 1842, p.xi.

- Symmons 1842, p.xxvi.

- Spehn-Jackson 2015, p.15.

External links

| Noongar test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |