Daisy Bates (author)

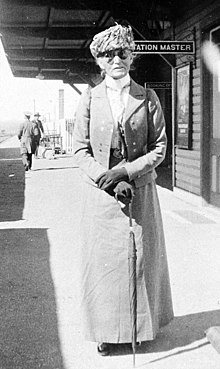

Daisy May Bates, CBE[1] (born Margaret Dwyer; 16 October 1859 – 18 April 1951) was an Irish-Australian journalist, welfare worker and lifelong student of Australian Aboriginal culture and society. Some Aboriginal people referred to Bates by the courtesy name Kabbarli "grandmother" (which is cognate with /kaparli/, a kin term in many Australian languages, and may also mean "granddaughter" in some contexts).[2]

Daisy Bates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Margaret Dwyer 16 October 1859 |

| Died | 18 April 1951 (aged 91) Adelaide, South Australia, Australia |

| Resting place | North Road Cemetery, Nailsworth, South Australia |

| Other names | Daisy May O'Dwyer, Daisy May Bates |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Spouse(s) | Harry Harbord 'Breaker' Morant, possible bigamous marriage to John (Jack) Bates and definite bigamous marriage to Ernest C. Baglehole |

| Children | Arnold Hamilton Bates |

Early life

Daisy Bates was born Margaret Dwyer in County Tipperary, Ireland in 1859. Her mother, Bridget (née Hunt), died of tuberculosis in 1862. Her father, James Edward O'Dwyer, married Mary Dillon in 1864 and died en route to the United States, so she was raised in Roscrea by relatives, and educated at the National School in that town.

Emigration and life in Australia

In November 1882, Dwyer—who by then had changed her first name to Daisy May—emigrated to Australia aboard the RMS Almora as part of a Queensland government assisted immigration scheme. Some accounts (based on Dwyer's own claims) say that she left Ireland for "health reasons", but biographer Julia Blackburn discovered that after getting her first job as a governess in Dublin at age 18, there was a scandal, presumably sexual in nature, which resulted in the young man of the house taking his own life. This story has never been verified, but if true, could have spurred Dwyer to leave Ireland and reinvent her history, setting a pattern for the rest of her life.[3] It was not until long after her death that the truth about her early life emerged,[4] and even her recent biographers have produced differing accounts of her life and work.[5]

Dwyer settled first at Townsville, Queensland allegedly staying first at the home of the Bishop of North Queensland and later with family friends who had migrated earlier. Dwyer had travelled with Ernest C. Baglehole and James C. Hann, amongst others, on the later stage of her journey. Both Baglehole and Hann had boarded at Batavia for the journey to Australia. Hann's family, through William Hann's donation of £1000, had been very generous to the construction of St James Church of England some few years before Bishop Stanton had arrived at Townsville. She subsequently found employment as a governess on Fanning Downs Station.

Records show that she married poet and horseman Breaker Morant (Harry Morant aka Edwin Murrant) on 13 March 1884 in Charters Towers; the union lasted only a short time and Dwyer reputedly threw Morant out because he failed to pay for the wedding and stole some livestock.[6] The marriage was not in fact legal, as Morant was underage (he declared himself to be twenty-one, when he was actually nineteen).[7][8] Significantly, they were never divorced. Morant biographer Nick Bleszynski suggests that Dwyer played a more important role in Morant's life than has been previously thought, and that it was she who convinced him to change his name from Edwin Murrant to Harry Harbord Morant.

After parting ways with Morant, Dwyer moved to New South Wales. She said that she became engaged to Philip Gipps (the son of a former governor) but he died before they could marry, though no records support this. Her biographer, Bob Reece, calls this story 'nonsense', as Gipps in fact died in February 1884, before her marriage to Morant.[9]

She then met John (Jack) Bates—like Morant, a bushman and drover—and they married on 17 February 1885. Their only child, Arnold Hamilton Bates, was born in Bathurst, New South Wales on 26 August 1886. It is possible that Ernest Baglehole, not Bates, was Arnold's father.[8] The marriage was not a happy one, probably because Jack's work kept him away from home for long periods.

She also found time to marry Ernest Baglehole, her emigration voyage shipmate, on 10 June 1885[8] at St Stephen's Anglican Church, Newtown, Sydney. Although he is shown as being a seaman, he was the son of a wealthy London family and had become a ship's officer after completing an apprenticeship and this might have been an attraction for Daisy. The polygamous nature of these marriages was kept secret during Bates's lifetime.

In February 1894, Bates returned to England, leaving Arnold in a Catholic boarding school and telling Jack that she would only return when he had a home established for her. She arrived in England penniless, but eventually found a job working for journalist and social campaigner WT Stead. Despite her skeptical views she worked as an assistant editor on the psychic quarterly Borderlands, and enjoyed an active intellectual life among London's well-connected and bohemian literary and political milieu. However, after she left Stead's employment in 1896, it is unclear how she supported herself until 1899, when she embarked for Western Australia after Jack wrote to say that he was looking for a property there.[10]

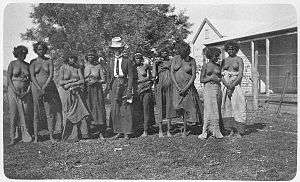

Involvement with Australian Aboriginal people

Bates's involvement with the Aboriginal Australians was not as a missionary, doctor or teacher. The foreword of her book written by Alan Moorehead said, " As far as I can make out she never tried to teach the Australians Aborigines anything or convert them to any faith. She preferred them to stay as they were and live out the last of their days in peace." Alan Moorehead also said, "She was not an anthropologist but she knew them better than anyone else who ever lived; and she made them interesting not only to herself but to us as well."

At about 1899 a letter was published in The Times about the cruelty of West Australian settlers to Aborigines. As Bates was preparing to return to Australia, she wrote to The Times offering to make full investigations and report the results to them. Her offer was accepted and she sailed back to Australia in August 1899. In all, Bates devoted 40 years of her life to studying Aboriginal life, history, culture, rites, beliefs and customs. She researched and wrote on the subject while living in a tent in small settlements from Western Australia to the edges of the Nullarbor Plain, including at Ooldea in South Australia. She was also famed for her strict lifelong adherence to Edwardian fashion, including boots, gloves and a veil.

Bates set up camps to feed, clothe and nurse the transient population, drawing on her own income to meet the needs of the aged. She was said to have worn pistols even in her old age and to have been quite prepared to use them to threaten police when she caught them mistreating "her" Aborigines.

Bates was convinced that the Australian Aborigines were a dying race and that her mission was to record as much as she could about them before they disappeared.[11] In a 1921 article in the Perth Sunday Times,[12] Bates advocated a "woman patrol" to prevent the movement of Aborigines from the Central Australian Reserve into settled areas, and later responded to criticism by the Aboriginal civil-rights leader William Harris, who maintained that part-Aboriginal people could be of value to Australian society, by writing that "As to the half-castes, however early they may be taken and trained, with very few exceptions, the only good half-caste is a dead one."[13]

Western Australia

On her return voyage she met Father Dean Martelli, a Roman Catholic priest who had worked with Aborigines and who gave her an insight into the conditions they faced. She found a school and home for her son in Perth, invested some of her money in property as a security for her old age, bought note books and supplies and left for the state's remote north-west to gather information on Aborigines and the effects of white settlement.

She wrote articles about conditions around Port Hedland and other areas for geographical society journals, local newspapers and The Times. This experience kindled her lifelong interest in the lives and welfare of Aboriginal people in Western and South Australia.

Based at the Beagle Bay Mission near Broome, Bates, now thirty-six, began her life's work. Her accounts, among the first attempts at a serious study of Aboriginal culture, were published in the Journal of Agriculture and later by anthropological and geographical societies in Australia and overseas.

While at the mission she also compiled a local dictionary of several dialects, comprising some two thousand words and sentences, as well as notes on legends and myths. In April 1902 Bates, accompanied by her son and her husband, set out on a droving trip from Broome to Perth. It provided good material for her articles but after spending six months in the saddle and travelling four thousand kilometres, Bates knew that her marriage was over.

Following her final separation from Bates in 1902, she spent most of the rest of her life in outback Western and South Australia, studying and working for the remote Aboriginal tribes, who were being decimated by the incursions of European settlement and the introduction of modern technology, western culture and exotic diseases.

In 1904, the Registrar General of Western Australia, Malcolm Fraser,[14] appointed her to research Aboriginal customs, languages and dialects, a task which took nearly seven years to compile and arrange the data. Many of her papers were read at Geographical and Royal Society meetings.

In 1910–11 she accompanied anthropologist A. R. Brown (later Professor Alfred Radcliffe-Brown) and writer and biologist E. L. Grant Watson on a Cambridge ethnological expedition to inquire into Western Australian marriage customs. She was appointed a "Travelling Protector" with a special commission to conduct inquiries into all native conditions and problems, such as employment on stations, guardianship and the morality of native and half-caste women in towns and mining camps.

Legend has it that Bates later came into conflict with Radcliffe-Brown because she sent him her manuscript report of the expedition. Much to Bates's chagrin, it was not returned for many years and when it came back it was heavily annotated with Radcliffe-Brown's critical remarks. The conflict culminated in a famous incident at a symposium, where Bates accused Radcliffe-Brown of plagiarism—Bates was scheduled to speak after Radcliffe-Brown had presented his paper, but when she rose it was only to compliment him sarcastically on his presentation of her work, after which she resumed her seat.

A "Protector of Aborigines"

After 1912, despite having earlier been appointed as Travelling Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, her application to become the Northern Territory's Protector of Aborigines was rejected on basis of her gender, Bates continued her work on her own, financing it by selling her cattle station.

The same year she became the first woman ever to be appointed Honorary Protector of Aborigines at Eucla. During the sixteen months she spent there, Bates changed from a semi-professional scientist and ethnologist to a staunch friend and protector of the Aborigines, deciding to live among them and look after them, and to observe and record their lives and lifestyle.

Bates stayed at Eucla until 1914, when she travelled to Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney to attend the Science Congress of the Association for the Advancement of Science. Before returning to the desert, she gave lectures in Adelaide which aroused the interests of several women's organisations.

During her years at Ooldea she financed the supplies she bought for the Aborigines from the sale of her property. To maintain her income she wrote numerous articles and papers for newspapers, magazines and learned societies. Through journalist and author Ernestine Hill, Bates's work was introduced to the general public, although much of the publicity tended to focus on her sensational stories of cannibalism.

In August 1933 the Commonwealth Government invited Bates to Canberra to advise on Aboriginal affairs. The next year she was created a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by King George V. More important to Bates was the opportunity to put her work in print.

South Australia

She left Ooldea and went to Adelaide where, with the help of Ernestine Hill, she produced a series of articles for leading Australian newspapers, titled My Natives and I.[15]

Aged seventy-one, she still walked every day to her office at The Advertiser building. Later the Commonwealth Government paid her a stipend of $4 a week to assist her in putting all her papers and notes in order and prepare her manuscript. But with no other income it was impossible for her to remain in Adelaide so she moved to the village settlement of Pyap on the Murray River where she pitched her tent and set up her typewriter.

In 1938, she published The Passing of the Aborigines[16] which asserted practices of cannibalism and infanticide.[17]

Final years

In 1941 she went back to her tent life at Wynbring Siding, east of Ooldea, and she remained there on and off until her health forced her back to Adelaide in 1945.

In 1948 she tried, through the Australian Army, to contact her son Arnold, who had served in France during World War I. Later, in 1949, she contacted the Army again, through the RSL, in an effort to communicate with him[18]. Arnold was living in New Zealand but refused to have anything to do with his mother.

Daisy Bates died on 18 April 1951, aged 91. She is buried at Adelaide's North Road Cemetery.

Recognition and memberships

- Bates was elected a member of the Royal Geographical Society (Melbourne).

- She was elected a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Society of Australasia (F.R.A.S.) in 1907.[19]

- She was appointed an honorary corresponding member of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- She was made a CBE in 1934

Digital database

The collaborative work of digitising and transcribing many word lists created by Bates in the 1900s at Daisy Bates Online[20] provides a valuable resource for those researching especially Western Australian languages, and some of the Northern Territory and South Australia.[21] The project is co-ordinated by Nick Thieburger, who works in collaboration with the National Library of Australia "to have all the microfilmed images from Section XII of the Bates papers digitised", and the project is ongoing.[22]

In popular culture

Sidney Nolan's 1950 painting Daisy Bates at Ooldea shows Bates standing in a barren outback landscape. It was acquired by the National Gallery of Australia.[23] An episode in her life was the basis for Margaret Sutherland's chamber opera The Young Kabbarli (1964). Choreographer Margaret Barr represented Bates in two dance dramas, Colonial portraits (1957),[24] and Portrait of a Lady with the CBE (1971).[25] In 1972, ABC TV screened Daisy Bates, a series of four 30 minute episodes, written by James Tulip, produced by Robert Allnutt, with art by Guy Gray Smith; choreography and reading by Margaret Barr, danced by Christine Cullen; music composed by Diana Blom, sung by Lauris Elms.[26] Her involvement with the Aboriginal people is the basis for the 1983 lithograph The Ghost of Kabbarli by Susan Dorothea White.

References

- Australian Women Biographical entry

- Glass, A. and D. Hackett, (2003) Ngaanyatjarra and Ngaatjatjarra to English Dictionary Alice Springs, IAD Press. ISBN 1-86465-053-2, p39

- Reece, Bob (18 October 2009). "The Irishness of Daisy Bates" (PDF). Australian-Irish Heritage Association. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

Was her departure hastened by a young man of good family committing suicide on her account? We shall never know.

- de Vries, Susanna. "Desert Queen: the Many Lives and Loves of Daisy Bates". Susanna de Vries. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Jones, Philip (5 March 2008). "Native entitlement". Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Maloney, Shane (June 2007). "Daisy Bates & Harry 'Breaker' Morant". The Monthly. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Reece, Bob (2007a). Daisy Bates: Grand Dame of the Desert. Canberra: National Library of Australia. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-64-227654-4. OCLC 212893816.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Joe; Roper, Roger (2016). Breaker Morant: The final roundup. Stroud, Gloucesteshire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-44-565965-7. OCLC 976033815.

- Reece (2007a), p. 21.

- Reece, Bob (2007b). "'You would have loved her for her lore': the letters of Daisy Bates". Australian Aboriginal Studies (1): 51–70. ISSN 0729-4352. Retrieved 19 June 2018 – via The Free Library.

- "The Passing of the Aborigines, by Daisy Bates : Epilogue". ebooks.adelaide.edu.au. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Bates, Daisy (12 June 1921). "New Aboriginal Reserve". Sunday Times. (Perth, WA : 1902 - 1954): via National Library of Australia. p. 8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Reece (2007a), pp. 89–90.

- Lomas, Brian D. (2015). Queen of Deception. Amazon. ISBN 978-0-646-94238-4.

- "MY NATIVES AND I". The Nowra Leader. New South Wales, Australia. 27 August 1937. p. 2. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Bates, Daisy (1938), The passing of the Aborigines : a lifetime spent among the natives of Australia (1st ed.), Murray, ISBN 978-0-7195-0071-8

- "LATEST in the BOOK SHOPS". Weekly Times (3720). Victoria, Australia. 14 January 1939. p. 34. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Aborigines Friend Daisy Bates Seeks Her Son". The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1950). 4 July 1949. p. 7. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "Mrs. Daisy M. Bates, F.R.A.S." Western Mail. XXIII (1, 158). Western Australia. 7 March 1908. p. 15. Retrieved 1 January 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Digital Daisy Bates". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Map". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Technical details". Digital Daisy Bates. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Nolan, Sidney | Daisy Bates at Ooldea, National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- R.R. (12 September 1964). "Program of Four Ballets". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, New South Wales. p. 8. Retrieved 1 May 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Pask, Edward (1982). Ballet in Australia: the Second Act, 1940-1980. OUP. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9780195542943. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Anderson, Don (29 April 1972). "Daisy Bates, superstar". The Bulletin. 94 (4802): 41. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

Works cited

- Daisy Bates (17 December 2014) [1938]. The Passing of the Aborigines: a Lifetime spent among the Natives of Australia. The University of Adelaide Library.

- Wright, R. V. S. (1979). "Bates, Daisy May (1863–1951)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 7. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 19 February 2017 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Further reading

- Blackburn, Julia. (1994) Daisy Bates in the Desert: A Woman's Life Among the Aborigines London, Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-436-20111-9

- De Vries, Susanna. (2008) Desert Queen: The many lives and loves of Daisy Bates Pymble, N.S.W. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7322-8243-1

- Lomas, Brian D. (2015). Queen of Deception. Amazon. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-646-94238-4.

External links

- "Daisy Bates". Flinders Ranges Research. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- "Seven Sisters" – includes a collection of quotes by and about Daisy Bates

- Daisy Bates – A list of her papers held by University of Adelaide Library

- Daisy Bates – Guide to the papers at the National Library of Australia (including the rare maps)

- Daisy May Bates – Guide to records at the South Australian Museum Archives

- Works by Daisy Bates at Project Gutenberg Australia

- The Ghost of Kabbarli (Daisy Bates), lithograph (1983) by Susan Dorothea White

- Digital Daisy Bates – a project in the School of Languages and Linguistics at The University of Melbourne

- Bates, Daisy May (1859–1951) in The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia