Mineng

Mineng, also spelled Minang or Menang or Mirnong, are an indigenous Noongar people of southern Western Australia.

Name

The ethnonym Minang is etymologized to the word for south, minaq, which means that the tribe were defined as "southerners".[1]

Country

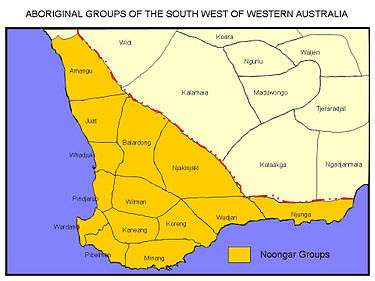

The Minang's traditional lands encompassed some 4,900 square miles (13,000 km2) from King George Sound northwards to the Stirling Range. It took in Tenterden, Lake Muir, Cowerup and the Shannon River area. Along the coast their territory ran from West Cliff Point to Boat Harbour, Pallinup. Mount Barker, Nornalup, Wilson Inlet and Porongurup Range were also part of their territory.[1]

Social organization

The Minang were divided into hordes. A northerly group of these, known as the Munite, perhaps may refer to the "White Cockatoo" tribe mentioned in other sources.[1]

History of contact

Norman Tindale[1] mentions a passage in Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle which may reflect an encounter with the Minang. Describing his 8-day sojourn in the King George Sound, he stated that "we did not during our voyage pass a more dull and uninteresting time",[2] save for a performance given by the Cockatoo tribe:

A large tribe of natives, called the White Cockatoo men, happened to pay the settlement a visit while we were there. These men, as well as those of the tribe belonging to King George's Sound, being tempted by the offer of some tubs of rice and sugar, were persuaded to hold a corrobery, or great dancing-party. As soon as it grew dark, small fires were lighted, and the men commenced their toilet, which consisted in painting themselves white in spots and lines. As soon as all was ready, large fires were kept blazing, round which the women and children were collected as spectators; the Cockatoo and King George's men formed two distinct parties, and generally danced in answer to each other. The dancing consisted in their running either sideways or in Indian file into an open space, and stamping the ground with great force as they marched together. Their heavy footsteps were accompanied by a kind of grunt, by beating their clubs and spears together, and by various other gesticulations, such as extending their arms and wriggling their bodies. It was a most rude, barbarous scene, and, to our ideas, without any sort of meaning; but we observed that the black women and children watched it with the greatest pleasure. Perhaps these dances originally represented actions, such as wars and victories. There was one called the Emu dance, in which each man extended his arm in a bent manner, like the neck of that bird. In another dance, one man imitated the movements of a kangaroo grazing in the woods, whilst a second crawled up, and pretended to spear him. When both tribes mingled in the dance, the ground trembled with the heaviness of their steps, and the air resounded with their wild cries. Every one appeared in high spirits, and the group of nearly naked figures, viewed by the light of the blazing fires, all moving in hideous harmony, formed a perfect display of a festival amongst the lowest barbarians. In Tierra del Fuego, we have beheld many curious scenes in savage life, but never, I think, one where the natives were in such high spirits, and so perfectly at their ease. After the dancing was over, the whole party formed a great circle on the ground, and the boiled rice and sugar was distributed, to the delight of all.[3]

Culture

One of the most famous singers of the Noongar peoples was a Mineng man, Nebinyan, who had worked many years as a hand on a whaling ship in the coastal waters of the Indian Ocean and the Great Australian Bight, and lived to achieve distinction as a singer of the narrative songs he wove around his experiences. One particular song, on a whale hunt, was heard and admired by Daisy Bates, who jotted down details, but failed to record it.[4] Another performance by Nebinyan, transmitting a dance his grandfather had created to mimic what he had observed when Matthew Flinders had set foot on the southern coast a century earlier, was also greatly admired.[5]

Present day

The Minang now predominantly live in and around Albany and the surrounding South Coast area of Western Australia.[6]

Alternative names

- Mean-anger, Meernanger

- Meenung (Koreng exonym)

- Minnal Yungar ("southern men")

- Minung, Meenung

- Mirnong

- Mount Barker tribe

Source: Tindale 1974, p. 248

Some words

- janka (whiteman)

- mam (father)

- moking (wild dog)

- nginung, ngyank, nonk (mother)

- nop, kooling (baby)

- twert (tame dog)

Source: Spencer, Hossell & Knight 1886

Notes

Citations

- Tindale 1974, p. 248.

- Darwin 1860, p. 442.

- Darwin 1860, pp. 443–444.

- Gibbs 2003, pp. 1–13.

- White 1980, pp. 33–42.

- Glossary.

Sources

- "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". AIATSIS.

- Clark, William Nairne (16 February 1842a). "An inquiry respecting the aborigines of south-western Australia". Perth. Australia: Inquirer. pp. 4–5 – via Trove.

- Clark, William Nairne (23 February 1842b). "An inquiry respecting the aborigines of south-western Australia 2". Perth. Australia: Inquirer. pp. 4–5 – via Trove.

- Clark, William Nairne (2 March 1842c). "An inquiry respecting the aborigines of south-western Australia 3". Perth, Australia: Inquirer. p. 4 – via Trove.

- Darwin, Charles (1860) [First published 1839]. Journal of researches during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (PDF). Collins.

- Gibbs, Martin (2003). "Nebinyan's songs: an Aboriginal whaler of south-west Western Australia 2003" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 27: 1–13.

- "Glossary". Kaartdijin Noongar. South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Nind, Scott (1831). "Description of the Natives of King George's Sound (Swan River Colony) and Adjoining Country". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 1: 21–51. JSTOR 1797657.

- Spencer, W. A.; Hossell, J. A.; Knight, W. A. (1886). "King George's Sound. Minung tribe" (PDF). In Curr, Edward Micklethwaite (ed.). The Australian race: its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia and the routes by which it spread itself over the continent. Volume 1. Melbourne: J. Ferres. pp. 348–351.

- "Tindale Tribal Boundaries" (PDF). Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Western Australia. September 2016.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Minang (WA)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- White, Isobel (1980). "The birth and death of a ceremony" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 4: 33–42.