Yidiny language

Yidiny (also spelled Yidiɲ, Yidiñ, Jidinj, Jidinʲ, Yidinʸ, Yidiń IPA: [ˈjidiɲ]) is a nearly extinct Australian Aboriginal language, spoken by the Yidinji people of north-east Queensland. Its traditional language region is within the local government areas of Cairns Region and Tablelands Region, in such localities as Cairns, Gordonvale, and the Mulgrave River, and the southern part of the Atherton Tableland including Atherton and Kairi.[5]

| Yidiny | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Australia |

| Region | Queensland |

| Ethnicity | Yidinji, Gungganyji, Wanjuru, Madjandji |

Native speakers | 19 (2016 census)[1] |

Pama–Nyungan

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | yii |

| Glottolog | yidi1250[3] |

| AIATSIS[4] | Y117 |

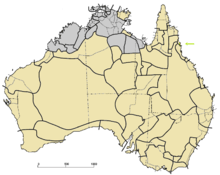

Yidiny (green, with arrow) among other Pama–Nyungan languages (tan) | |

Classification

Yidiny forms a separate branch of Pama–Nyungan. It is sometimes grouped with Djabugay as Yidinyic, but Bowern (2011) retains Djabugay in its traditional place within the Paman languages.[6]

Sounds

Vowels

Yidiny has the typical Australian vowel system of /a, i, u/. Yidiny also displays contrastive vowel length.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | b | d | ɟ | g | |

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Approximant | w | l | ɻ | j | |

| Rhotic | r |

Yidiny consonants, with no underlyingly voiceless consonants, are posited.[7]

It is not clear if the two rhotics are trill and flap, or tap and approximant. Dixon (1977) gives them as a "trilled apical rhotic" and a "retroflex continuant".[8]

Grammar

The Yidiny language has a number of particles that change the meaning of an entire clause. These, unlike other forms in the language, such as nouns, verbs and gender markers, have no grammatical case and take no tense inflections. The particles in the Yidiny language: nguju - 'not' (nguju also functions as the negative interjection 'no'), giyi - 'don't', biri - 'done again', yurrga - 'still', mugu - 'couldn't help it' (mugu refers to something unsatisfactory but that is impossible to avoid doing), jaymbi / jaybar - 'in turn'. E.g. 'I hit him and he jaymbi hit me', 'He hit me and I jaybar hit him'. Dixon[9] states that "pronouns inflect in a nominative-accusative paradigm… deictics with human reference have separate cases for transitive subject, transitive object, and intransitive subject… whereas nouns show an absolutive–ergative pattern." Thus three morphosyntactic alignments seem to occur: ergative–absolutive, nominative–accusative, and tripartite.

Pronouns and deictics

Pronoun and other pronoun-like words are classified as two separate lexical categories. This is for morphosyntactic reasons: pronouns show nominative-accusative case marking, while demonstratives, deictics, and other nominals show absolutive-ergative marking.[10]

Affixes

In common with several other Australian Aboriginal languages, Yidiny is an agglutinative ergative-absolutive language. There are many affixes which indicate a number of different grammatical concepts, such as the agent of an action (shown by -nggu), the ablative case (shown by -mu or -m), the past tense (shown by -nyu) and the present and future tenses (both represented with the affix -ng).

There are also two affixes which lengthen the last vowel of the verbal root to which they are added, -Vli- and -Vlda (the capital letter 'V' indicates the lengthened final vowel of the verbal root). For example: magi- 'climb up' + ili + -nyu 'past tense affix' (giving magiilinyu), magi- 'climb up' + ilda + -nyu 'past tense affix' (giving magiildanyu). The affix -Vli- means 'do while going' and the affix -Vlda- means 'do while coming'. It is for this reason that they cannot be added to the verbs gali- 'go' or gada- 'come'. Therefore, the word magiilinyu means 'went up, climbing' and magiildanyu means 'came up, climbing'.

One morpheme, -ŋa, is an applicative in some verbs and a causative in others. For example, maŋga- 'laugh' becomes applicative maŋga-ŋa- 'laugh at' while warrŋgi- 'turn around' becomes causative warrŋgi-ŋa- 'turn something around'. The classes of verbs are not mutually exclusive however, so some words could have both meanings (bila- 'go in' becomes bila-ŋa- which translates either to applicative 'go in with' or causative 'put in'), which are disambiguated only through context.[11]

Affixes and number of syllables

There is a general preference in Yidiny that as many words as possible should have an even number of syllables. It is for this reason that the affixes differ according to the word to which they are added. For example: the past tense affix is -nyu when the verbal root has three syllables, producing a word that has four syllables: majinda- 'walk up' becomes majindanyu in the past tense, whereas with a disyllabic root the final vowel is lengthened and -Vny is added: gali- 'go' becomes galiiny in the past tense, thus producing a word that has two syllables. The same principle applies when forming the genitive: waguja- + -ni = wagujani 'man's' (four syllables), bunya- + -Vn- = bunyaan 'woman's'. The preference for an even number of syllables is retained in the affix that shows a relative clause: -nyunda is used with a verb that has two or four syllables (gali- (two syllables) 'go' + nyunda = galinyunda), giving a word that has four syllables whereas a word that has three or five syllables takes -nyuun (majinda- (three syllables) 'walk up' + nyuun = majindanyuun), giving a word that has four syllables.[12]

Some words

- bunggu. 'Knee,' but more extensively: 'That part of the body of anything which, in moving, enables the rest of the body or object to be propelled.' This is used of the hump in a snake's back as it wriggles, the swish point of a crocodile's tail, or the wheel of a car or tractor.[13]

- jilibura. 'Green (tree) ant'. It was squeezed, and the 'milk' it yielded was then mixed with the ashes of a gawuul (blue gum tree), or from a murrgan (quandong) or a bagirram tree, and the concoction then drunk to clear headaches. The classifier used for ants,munyimunyi was used for all species, such as the gajuu (black tree ant) and burrbal, (red ant), but never for a jilibura because it was different, having a medicinal use.[14]

References

- "Census 2016, Language spoken at home by Sex (SA2+)". stat.data.abs.gov.au. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge University Press. p. xxxiii.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Yidiñ". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Y117 Yidiny at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

-

- Bowern, Claire. 2011. "How Many Languages Were Spoken in Australia?", Anggarrgoon: Australian languages on the web, December 23, 2011 (corrected February 6, 2012)

- "A Grammar of Yidiɲ", by R. M. W. Dixon, 1977, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. P. 32

- "A Grammar of Yidiɲ", by R. M. W. Dixon, 1977, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. P. 32

- "A Grammar of Yidiɲ", by R. M. W. Dixon, 1977, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dixon, R.M.W. 1977. A Grammar of Yidiny. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cited in Bhat, D.N.S. 2004. Pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 4–5

- Dixon, R.M.W. (2000). "A Typology of Causatives: Form, Syntax, and Meaning". In Dixon, R.M.W. & Aikhenvald, Alexendra Y. Changing Valency: Case Studies in Transitivity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–32.

- R.M.W. Dixon, Searching for Aboriginal Languages, pages 247-251, University of Chicago Press, 1989

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2011). Searching for Aboriginal Languages: Memoirs of a Field Worker. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-108-02504-1.

- Dixon (2011), 298–299.

Further reading

- R. M. W. Dixon. (1977). A Grammar of Yidiny. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- R. M. W. Dixon. (1984, 1989). Searching for Aboriginal Languages. University of Chicago Press.