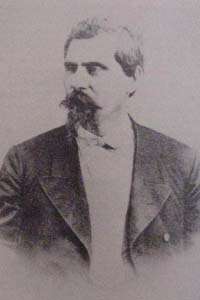

John Rollin Ridge

John Rollin Ridge (Cherokee name: Cheesquatalawny, or Yellow Bird,[1] March 19, 1827 – October 5, 1867), a member of the Cherokee Nation, is considered the first Native American novelist.

John Rollin Ridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Chee-squa-ta-law-ny (Yellow Bird)--more accurately, "tsisgwa daloni" March 19, 1827 New Echota, Cherokee Nation (now Georgia) |

| Died | October 5, 1867 (aged 40) |

| Cause of death | encephalitis lethargia ("Brain fever") |

| Resting place | Grass Valley, California |

| Nationality | American, British |

| Other names | Chee-squa-ta-law-ny (Yellow Bird) |

| Citizenship | London |

| Occupation | Novelist, newspaperman |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Wilson |

| Parent(s) | John Ridge Sarah Bird Northrup |

| Signature | |

Biography

Early life and education

Born in New Echota, Georgia, he was the son of John Ridge, and the grandson of Major Ridge, both of whom were signatories to the Treaty of New Echota, which Congress affirmed in early 1836, ceding Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi River and ultimately leading to the Trail of Tears. At the age of twelve, Ridge witnessed his father's death at the hands of supporters of Cherokee leader John Ross, who had vehemently opposed the treaty. His mother, Sarah Bird Northrup (a white woman), took him and fled to Fayetteville, Arkansas. In 1843, he was sent to the Great Barrington School in Great Barrington, Massachusetts for two years, after which he returned to Fayetteville to study law.[2] It was during this period that his first known writing appeared in print. He published a poem, "To a Thunder Cloud," in the Arkansas State Gazette.[3] He married Elizabeth Wilson, a white woman, in 1847. They had one daughter, Alice, in 1848.

On the run

In 1849, he killed Ross sympathizer David Kell, whom he thought had been involved with his father's assassination, over a horse dispute.[1] Despite having a good argument for self-defense, he fled to Missouri to avoid prosecution.[4] The next year, he joined in the California Gold Rush, but disliked being a miner.[2] While there, he was reunited with his wife and daughter.[5]

Writing career

His writing career began with poetry (published posthumously)[2] and essays for the Democratic Party before what is now considered the first Native American novel and the first novel written in California, The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit (1854).[1] A fictionalized version of the notorious bandit's story, the tale describes a young Mexican who comes to California to seek his fortune during the Gold Rush and turns to crime after his wife is raped and his brother murdered by white men. This novel, which condemned American racism especially towards Mexicans, later inspired the Zorro stories. Although widely popular, Ridge saw no money from the book's publication—by the time of his death it had not yet even turned a profit.[6]

Ridge was a writer and the first editor of the Sacramento Bee and also wrote for the San Francisco Herald, among other publications.[1] As an editor, he advocated assimilationist policies for American Indians as his father had, placing his trust in the federal government to protect their rights. At the same time, however, he was blind to the ways in which those rights were continually abused by the same government.[2] Despite his novel's stance against racism, Ridge had owned slaves on his Arkansas property[1] and felt that California Indians were inferior to those of other tribes.[5]

The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta

Ridge's novel, one of the earliest by a Native American author, is curious both because it is written not about a Native American subject, but about a Mexican immigrant, and because it is not original but based on a legendary figure widely discussed in the media of the day. Ridge presents the figure of Joaquin Murieta as that of a young, innocent and industrious man who is hampered in his attempts to be successful in the United States by the racism of the people and by the 1850 Foreign Miner's Tax Law, which severely hampered the ability of Latinos to mine for gold. Ridge's version of Murieta becomes a bandit who attracts a large number of associates and who terrorizes the state of California for several months with his gruesome acts of violence. At the same time, Ridge's Murieta is a romantic figure, often showing kindness (especially to women) and relishing the stories about him, even as he keeps his identity so well secret that he can walk through town in broad daylight with no one recognizing him.

Although the novel is fictional, many people took it as fact and some historians even cited it when writing biographical materials on Murrieta.[6]

Civil War and the Southern Cherokee delegation

During the Civil War, Ridge openly supported the "Copperheads" and opposed both the election of Abraham Lincoln as well as the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, blaming the war on abolitionists.[2]

After the war, Ridge was invited by the federal government to head the Southern Cherokee delegation in postwar treaty proceedings. Despite his best efforts, the Cherokee region was not admitted as a state to the Union.[2]

Death

In December 1866, Ridge returned to his home in Grass Valley, California, where he died of "brain fever" (Encephalitis lethargica) on October 5, 1867.[7] He was buried at Greenwood Memorial Park in Grass Valley.[8]

Bibliography

- The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit (San Francisco: W.B. Cooke and Company, 1854) (San Francisco: Fred MacCrellish & Co., 3rd ed., 1871) (Hollister, California: Evening Free Lance, 1927) (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955) (University of Oklahoma Press, 1969)

- Poems, by a Cherokee Indian, with an Account of the Assassination of His Father, John Ridge (San Francisco: H. Payot, 1868)

- The Lives of Joaquin Murieta and Tiburcio Vasquez; the California Highwaymen (San Francisco: F. MacCrellish & Co., 1874)

- California's Age of Terror: Murieta and Vasquez (Hollister, California: Evening Free Lance, 1927)

- Crimes and Career of Tiburcio Vasquez, the Bandit of San Benito County and Notorious Early California Outlaw (Hollister, California: Evening Free Lance, 1927)

References

- "John Rollin Ridge (1827-1867)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 20, 2005.

- "Ridge, John Rollin (Yellow Bird)". Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Archived from the original on February 12, 2006. Retrieved February 23, 2006.

- Gordon Fraser. "Yellow Bird and the Thunder: On Finding the Earliest Known Poem by John Rollin Ridge, the First Native American Novelist." Common-place. 14.4 (2014). http://www.common-place.org/vol-14/no-04/tales/#.VNU_6NLF-So

- Somerville, Richard (November 1, 2003). "The legendary life of John Rollin Ridge". The Union. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- Noy, Gary (September 17, 2005). "The California Bandit and Yellow Bird". The Union.

- "John Rollin Ridge (Yellow Bird) (1827-1867)". American Passages: A Literary Survey. Retrieved February 23, 2006.

- " American Indian Biography: John Rollin Ridge, Cherokee Writer." Posted by Ojibwa on Native American Netroots, January 4, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- Alice Huitt Preston (4 September 2004). "John Rollin Ridge". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

Further reading

- Parins, James (1991). John Rollin Ridge: His Life and Works. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8780-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Rollin Ridge. |