Mulatto

Mulatto (/mjuːˈlætoʊ/, /məˈlɑːtoʊ/) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed white and black ancestry.[3][4][5] A Mulatta is a female Mulatto.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| No official worldwide estimates | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| South America, Caribbean, Southern Africa, North America, Northwestern Europe | |

| c. 84 million multiracial people with european and african background, as well as others, see Pardo Brazilian | |

| c. 8 million | |

| c. 4.7 million (2012)[1] | |

| c. 4.6 million (2011) | |

| c. 1.8 million (2010)[2] | |

| c. 8 million | |

| c. 1 million | |

| c. ~600,000 (2011) | |

| 85,037 | |

| 300,000 | |

| Languages | |

| English creoles, French creoles, Spanish creoles, Portuguese creoles, Languages of Europe, Languages of Africa | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pardos | |

Etymology

The English term mulatto is derived from the Spanish and Portuguese mulato. The origin of mulato is uncertain, though it may derive from Portuguese mula (from the Latin mūlus), meaning mule, the hybrid offspring of a horse and a donkey.[6][7] The Real Academia Española traces its origin to mulo in the sense of hybridity; originally used to refer to any mixed race person.[8]

Jack D. Forbes suggests it originated in the Arabic term muwallad, which means "a person of mixed ancestry".[9] Muwallad literally means "born, begotten, produced, generated; brought up", with the implication of being born and raised among Arabs, but not of Arab blood. Muwallad is derived from the root word WaLaD (Arabic: ولد direct Arabic transliteration: waw, lam, dal), and colloquial Arabic pronunciation can vary greatly. Walad means, "descendant, offspring, scion; child; son; boy; young animal, young one".

In al-Andalus, Muwallad referred to the offspring of non-Arab/Muslim people who adopted the Islamic religion and manners. Specifically, the term was historically applied to the descendants of indigenous Christian Iberians who, after several generations of living among a Muslim majority, adopted their culture and religion. Notable examples of this category include the famous Muslim scholar Ibn Hazm. According to Lisan al-Arab, one of the earliest Arab dictionaries (c. 13th century AD), applied the term to the children of Non-Muslim (often Christian) slaves, or Non-Muslim children who were captured in a war and were raised by Muslims to follow their religion and culture. Thus, in this context, the term "Muwalad" has a meaning close to "the adopted". According to the same source, the term does not denote being of mixed-race but rather being of foreign-blood and local culture.

In English, printed usage of mulatto dates to at least the 16th century. The 1595 work Drake's Voyages first used the term in the context of intimate unions producing biracial children. The Oxford English Dictionary defined mulatto as "one who is the offspring of a European and a Black". This earliest usage regarded "black" and "white" as discrete "species", with the "mulatto" constituting a third separate "species".[10]

According to Julio Izquierdo Labrado,[11] the 19th-century linguist Leopoldo Eguilaz y Yanguas, as well as some Arabic sources[12] muwallad is the etymological origin of mulato. These sources specify that mulato would have been derived directly from muwallad independently of the related word muladí, a term that was applied to Iberian Christians who had converted to Islam during the Moorish governance of Iberia in the Middle Ages.

The Real Academia Española (Spanish Royal Academy) casts doubt on the muwallad theory. It states, "The term mulata is documented in our diachronic data bank in 1472 and is used in reference to livestock mules in Documentacion medieval de la Corte de Justicia de Ganaderos de Zaragoza, whereas muladí (from mullawadí) does not appear until the 18th century, according to [Joan] Corominas".[nb 1]

Scholars such as Werner Sollors cast doubt on the mule etymology for mulatto. In the 18th and 19th centuries, racialists such as Edward Long and Josiah Nott began to assert that mulattoes were sterile like mules. They projected this belief back onto the etymology of the word mulatto. Sollors points out that this etymology is anachronistic: "The Mulatto sterility hypothesis that has much to do with the rejection of the term by some writers is only half as old as the word 'Mulatto.'"[14]

Africa

Of São Tomé and Príncipe's 193,413 inhabitants, the largest segment is classified as mestiço, or mixed race.[15] 71% of the population of Cape Verde is also classified as such.[16] The great majority of their current populations descend from unions between the Portuguese, who settled the islands from the 15th century onward, and black Africans they brought from the African mainland to work as slaves. In the early years, mestiços began to form a third-class between the Portuguese colonists and African slaves, as they were usually bilingual and often served as interpreters between the populations.

In Angola and Mozambique, the mestiço constitute smaller but still important minorities; 2% in Angola[17] and 0.2% in Mozambique.[18]

Mulatto and mestiço are not terms commonly used in South Africa to refer to people of mixed ancestry. The persistence of some authors in using this term, anachronistically, reflects the old-school essentialist views of race as a de facto biological phenomenon, and the 'mixing' of race as legitimate grounds for the creation of a 'new race'. This disregards cultural, linguistic and ethnic diversity and/or differences between regions and globally among populations of mixed ancestry.[19]

In Namibia, an ethnic group known as Rehoboth Basters, descend from historic liaisons between the Cape Colony Dutch and indigenous African women. The name Baster is derived from the Dutch word for "bastard" (or "crossbreed"). While some people consider this term demeaning, the Basters proudly use the term as an indication of their history. In the early 21st century, they number between 20,000 and 30,000 people. There are, of course, other people of mixed race in the country.

South Africa

In South Africa, Coloured is a term used to refer to individuals with some degree of sub-Saharan ancestry but subjectively 'not enough' to be considered black-African under the Apartheid era law of South Africa. Today these people self-identify as 'Coloured'. Other Afrikaans terms used include Bruinmense (translates to "brown people"), Kleurlinge (translates to "Coloured") or Bruin Afrikaners (translates to "brown Africans" and is used to distinguish them from the main body of Afrikaners (translates to "African") who are white). Under Apartheid law through the latter half of the 20th century, the government established seven categories of Coloured people: Cape Coloured, Cape Malay, Griqua and Other Coloured - the aim of subdivisions was to enhance the meaning of the larger category of Coloured by making it all encompassing. Legally and politically speaking, all people of colour were classified "black" in the non-racial terms of anti-Apartheid rhetoric of the Black Consciousness Movement.[20]

In addition to European ancestry, the Coloured people usually had some portion of Asian ancestry from immigrants from India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mauritius, Sri Lanka, China and/or Saint Helena. Based on the Population Registration Act to classify people, the government passed laws prohibiting mixed marriages. Many people who classified as belonging to the "Asian" category could legally intermarry with "mixed-race" people because they shared the same nomenclature.[20] There was extensive combining of these diverse heritages in the Western Cape.

In other parts of South Africa and neighboring states, the coloured usually were descendants of two primary ethnic groups - primarily Africans of various tribes and European colonists of various tribes, with generations of coloured forming families. The use of the term 'Coloured' has changed over the course of history. For instance, in the first census after the South African war (1912), Indians were counted as 'Coloured'. But before and after this war, they were counted as 'Asiatic'.[21]

In KwaZulu-Natal, most Coloureds (that were classified as "other coloureds") had British and Zulu heritage. Zimbabwean coloureds were descended from Shona or Ndebele mixing with British and Afrikaner settlers.

Griqua, on the other hand, are descendants of Khoisan and Afrikaner trekboers, with contributions from central Southern African groups.[22] The Griqua were subjected to an ambiguity of other creole people within Southern African social order. According to Nurse and Jenkins (1975), the leader of this "mixed" group, Adam Kok I, was a former slave of the Dutch governor. He was manumitted and provided land outside Cape Town in the eighteenth century. With territories beyond the Dutch East India Company administration, Kok provided refuge to deserting soldiers, refugee slaves, and remaining members of various Khoikhoi tribes.[20]

Afro-European tribes and clans

- Akus

- Americo-Liberians

- Amaros

- Fernandinos

- Gold Coast Euro-Africans

- Saro people

- Sherbro Hubris

- Sherbro Tuckers

- Sherbro Caulkers

- Sherbro Rogers

- Sherbro Clevelands

- Sierra Leone Creole people

Latin America and the Caribbean

Mulattoes in colonial Spanish America

Africans were transported by Portuguese slave traders to Spanish America starting in the early 16th century. Offspring of European Spaniards and African women resulted early on in mixed-race children, termed Mulattos. In Spanish law, the status of the child followed that of the mother, so that despite having a Spanish parent, their offspring were enslaved. The label Mulatto was recorded in official colonial documentation, so that marriage registers, censuses, and court documents allow research on different aspects of mulattos’ lives. Although some legal documents simply label a person a Mulatto/a, other designations occurred. In the sales of casta slaves in 17th-century Mexico City, official notaries recorded gradations of skin color in the transactions. These included mulato blanco or mulata blanca (white mulatto), for light-skinned slave. These were usually American-born (criollo) slaves. Some said categorized persons i.e.m 'mulata blanca.' used their light skin to their advantage if they escaped their unlawful and brutal incarceration from their criminal slave owners, thus 'passing' as free persons on color. Mulatos blancos often emphasized their Spanish parentage, and considered themselves and were considered separate from negros or pardos and ordinary mulattos. Darker mulatto slaves were often termed mulatos prietos or sometimes mulatos cochos.[23] In Chile, along with mulatos blancos, there were also españoles oscuros (dark Spaniards).[24]

There was considerable malleability and manipulation of racial labeling, including the seemingly stable category of mulatto. In a case that came before the Mexican Inquisition, a woman publicly identified as a mulatta was described by a Spanish priest, Diego Xaimes Ricardo Villavicencio, as "a white mulata with curly hair, because she is the daughter of a dark-skinned mulata and a Spaniard, and for her manner of dress she has flannel petticoats and a native blouse (huipil), sometimes silken, sometimes woolen. She wears shoes, and her natural and common language is not Spanish, but Chocho [an indigenous Mexican language], as she was brought up among Indians with her mother, from which she contracted the vice of drunkenness, to which she often succumbs, as Indians do, and from them she has also received the crime of [idolatry]." Community members were interrogated as to their understanding of her racial standing. Her mode of dress, very wavy hair and light skin confirmed for one witness that she was a mulatta. Ultimately though, her rootedness in the indigenous community persuaded the Inquisition that she was an India, and therefore outside of their jurisdiction.[25] Even though the accused physical features of a mulatta, her cultural category was more important. In colonial Latin America, mulatto could also refer to an individual of mixed African and Native American ancestry.[26]

English Dominican friar Thomas Gage spent over a decade in Mexico and Central America in the early 17th century, he converted to Anglicanism and later wrote of his travels, often disparaging Spanish American society and culture. In Mexico City, he observed in considerable detail the opulence of dress of women, saying "The attire of this baser sort of people of blackamoors and mulattoes (which are of a mixed nature, of Spaniards and blackamoors) is so light, and their carriage so enticing, that many Spaniards even of the better sort (who are too too [sic] prone to venery) disdain their wives for them...Most of these are or have been slaves, though love have set them loose, at liberty to enslave souls to sin and Satan."[27]

In the late 18th century, some mixed-race persons sought legal "certificates of whiteness" (cédulas de gracias al sacar), in order to rise socially and practice professions. American-born Spaniards (criollos) sought to prevent the approval of such petitions, since the "purity" of their own whiteness would be in jeopardy. They asserted their "purity of blood (limpieza de sangre) as white persons who had "always been known, held and commonly reputed to be white persons, Old Christians of the nobility, clean of all bad blood and without any mixture of commoner, Jew, Moor, Mulatto, or converso in any degree, no matter how remote."[28] Spaniards both American- and Iberian-born discriminated against pardos and mulattoes because of their "bad blood." One Cuban sought the grant of his petition in order to practice as a surgeon, a profession from which he was barred because of his mulatto designation. Royal laws and decrees prevented pardos and mulattoes from serving as a public notary, lawyer, pharmacist, ordination to the priesthood, or graduation from university. Mulattas declared white could marry a Spaniard.[29]

Gallery

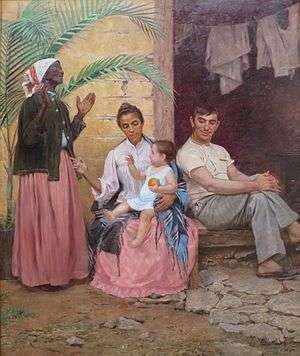

Casta painting of a Spaniard, a Negra and a Mulatto. José de Alcíbar, 18th c. Mexico

Casta painting of a Spaniard, a Negra and a Mulatto. José de Alcíbar, 18th c. Mexico De Español y Negra, Mulato. Anon. 18th c.

De Español y Negra, Mulato. Anon. 18th c. De Español y Negra, Mulato. José Joaquín Magón. 18th c. Mexico

De Español y Negra, Mulato. José Joaquín Magón. 18th c. Mexico De Español y Negra, Mulato. Anon.

De Español y Negra, Mulato. Anon. De negro y española, sale mulato (From a Black man and a Spanish woman, a Mulatto is begotten). Anon.

De negro y española, sale mulato (From a Black man and a Spanish woman, a Mulatto is begotten). Anon. De Español y Mulata, Morisca. Anon. 1799

De Español y Mulata, Morisca. Anon. 1799.jpg) De Mulata y Español, Morisca, Juan Patricio Morlete. 18th c. Mexico

De Mulata y Español, Morisca, Juan Patricio Morlete. 18th c. Mexico De Mulato y Mestiza, Torna atrás

De Mulato y Mestiza, Torna atrás De Negro y Mulata, Zambo. 18th c. Peru

De Negro y Mulata, Zambo. 18th c. Peru

Mulattoes in the modern era

Mulattoes represent a significant part of the population of various Latin American and Caribbean countries:[30] Dominican Republic (73%; all mixed-race people),[30][nb 2] Brazil (49.1% mixed-race, Gypsy and Black, Mulattoes (20.5%), Mestiços, Mamelucos or Caboclos (21.3%), Blacks (7.1%) and Eurasian (0.2%)),[31][32] Belize (25%), Colombia (10,4%),[30] Cuba (24.86%),[30] Haiti (15%).[30]

In the 21st century, persons with indigenous and black African ancestry in Latin America are more frequently called zambos in Spanish or cafuzo in Portuguese.

Brazil

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Porto Alegre (Rio Grande do Sul state) Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 9.3% | 5.3% | 85.5% | |

| Pardo | 15.4% | 42.4% | 42.2% | |

| Black | 11% | 45.9% | 43.1% | |

| Total | 9.6% | 12.7% | 77.7% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Ilhéus (Bahia state) Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 8.8% | 24.4% | 66.8% | |

| Pardo | 11.9% | 28.8% | 59.3% | |

| Black | 10.1% | 35.9% | 53.9% | |

| Total | 9.1% | 30.3% | 60.6% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Belém (Pará state) Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 14.1% | 7.7% | 78.2% | |

| Pardo | 20.9% | 10.6% | 68.6% | |

| Black | 20.1% | 27.5% | 52.4% | |

| Total | 19.4% | 10.9% | 69.7% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Fortaleza (Ceará state) Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 10.9% | 13.3% | 75.8% | |

| Pardo | 12.8% | 14.4% | 72.8% | |

| Black | N.S. | N.S. | N.S | |

Autosomal DNA studies (tables above and below) have shown the Brazilian population as a whole tends to have European, African and Native American components.

A 2015 autosomal genetic study, which also analysed data of 25 studies of 38 different Brazilian populations concluded that: European ancestry accounts for 62% of the heritage of the population, followed by the African (21%) and the Native American (17%). The European contribution is highest in Southern Brazil (77%), the African highest in Northeast Brazil (27%) and the Native American is the highest in Northern Brazil (32%).[34]

| Region[34] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 16% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 58% | 27% | 15% |

| Central-West Region | 64% | 24% | 12% |

| Southeast Region | 67% | 23% | 10% |

| South Region | 77% | 12% | 11% |

An autosomal study from 2013, with nearly 1300 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found a predominant degree of European ancestry combined with African and Native American contributions, in varying degrees. 'Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values up to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in the Northeast, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban

populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population'.[36]

| Region[37] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 17% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 56% | 28% | 16% |

| Central-West Region | 58% | 26% | 16% |

| Southeast Region | 61% | 27% | 12% |

| South Region | 74% | 15% | 11% |

An autosomal DNA study (2011), with nearly 1000 samples from all over the country ("whites", "pardos" and "blacks", according to their respective proportions), found a major European contribution, followed by a high African contribution and an important Native American component.[33] "In all regions studied, the European ancestry was predominant, with proportions ranging from 60.6% in the Northeast to 77.7% in the South".[38] The 2011 autosomal study samples came from blood donors (the lowest classes constitute the great majority of blood donors in Brazil[39]), and also public health institutions' personnel and health students. The study showed that Brazilians from different regions are more homogenous than previously thought by some based on the census alone. "Brazilian homogeneity is, therefore, a lot greater between Brazilian regions than within Brazilian regions".[40]

| Region[33] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brazil | 68.80% | 10.50% | 18.50% |

| Northeast of Brazil | 60.10% | 29.30% | 8.90% |

| Southeast Brazil | 74.20% | 17.30% | 7.30% |

| Southern Brazil | 79.50% | 10.30% | 9.40% |

According to a DNA study from 2010, "a new portrayal of each ethnicity contribution to the DNA of Brazilians, obtained with samples from the five regions of the country, has indicated that, on average, European ancestors are responsible for nearly 80% of the genetic heritage of the population. The variation between the regions is small, with the possible exception of the South, where the European contribution reaches nearly 90%. The results, published by the scientific magazine American Journal of Human Biology by a team of the Catholic University of Brasília, show that in Brazil, physical indicators such as skin colour, colour of the eyes and colour of the hair have little to do with the genetic ancestry of each person, which has been shown in previous studies (regardless of census classification).[41] "Ancestry informative SNPs can be useful to estimate individual and population biogeographical ancestry. Brazilian population is characterized by a genetic background of three parental populations (European, African, and Brazilian Native Amerindians) with a wide degree and diverse patterns of admixture. In this work we analyzed the information content of 28 ancestry-informative SNPs into multiplexed panels using three parental population sources (African, Amerindian, and European) to infer the genetic admixture in an urban sample of the five Brazilian geopolitical regions. The SNPs assigned apart the parental populations from each other and thus can be applied for ancestry estimation in a three hybrid admixed population. Data was used to infer genetic ancestry in Brazilians with an admixture model. Pairwise estimates of F(st) among the five Brazilian geopolitical regions suggested little genetic differentiation only between the South and the remaining regions. Estimates of ancestry results are consistent with the heterogeneous genetic profile of Brazilian population, with a major contribution of European ancestry (0.771) followed by African (0.143) and Amerindian contributions (0.085). The described multiplexed SNP panels can be useful tool for bioanthropological studies but it can be mainly valuable to control for spurious results in genetic association studies in admixed populations".[42] It is important to note that "the samples came from free of charge paternity test takers, thus as the researchers made it explicit: "the paternity tests were free of charge, the population samples involved people of variable socioeconomic strata, although likely to be leaning slightly towards the ‘‘pardo’’ group".[43]

| Region[43] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 71.10% | 18.20% | 10.70% |

| Northeast Region | 77.40% | 13.60% | 8.90% |

| Central-West Region | 65.90% | 18.70% | 11.80% |

| Southeast Region | 79.90% | 14.10% | 6.10% |

| South Region | 87.70% | 7.70% | 5.20% |

An autosomal DNA study from 2009 found a similar profile: "all the Brazilian samples (regions) lie more closely to the European group than to the African populations or to the Mestizos from Mexico".[44]

| Region[45] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 60.6% | 21.3% | 18.1% |

| Northeast Region | 66.7% | 23.3% | 10.0% |

| Central-West Region | 66.3% | 21.7% | 12.0% |

| Southeast Region | 60.7% | 32.0% | 7.3% |

| South Region | 81.5% | 9.3% | 9.2% |

According to another autosomal DNA study from 2008, by the University of Brasília (UnB), European ancestry dominates in the whole of Brazil (in all regions), accounting for 65.90% of heritage of the population, followed by the African contribution (24.80%) and the Native American (9.3%).[46]

Studies carried out by the geneticist Sergio Pena estimated the average white Brazilian also to have African and Native American ancestries, on average, this way: is 80% European, 10% Amerindian, and 10% African/black.[47] Another study, carried out by the Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, concludes the average white Brazilian is (>70%) European.[48]

According to the IBGE 2000 census, 38.5% of Brazilians identified as pardo, i.e. of mixed ancestry.[49][50] This figure includes mulatto and other multiracial people, such as people who have European and Amerindian ancestry (called caboclos), as well as assimilated, westernized Amerindians, and mestizos with some Asian ancestry. A majority of mixed-race Brazilians have all three ancestries: Amerindian, European, and African. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics census 2006, some 42.6% of Brazilian identify as pardo, an increase over the 2000 census.[51]

According to genetic studies, some of those who identify as White Brazilians (48.4%) also have some mixed-race ancestry (both Subsaharan African and Amerindian ancestry). Brazilians who identify as de raça negra or de cor preta, i.e. Brazilians of Black African origin, make up 6.9% of the population; genetic studies show their average total ancestry is still mixed: 40% African, 50% European, and 10% Amerindian, but they likely grew up within visibly black communities.

Such autosomal DNA studies, which measure total genetic contribution, continue to reveal differences between how individuals identify, which is usually based in family and close community, with genetic ancestry, which may relate to a distant past they know little about.[52] An autosomal DNA study from Rio de Janeiro poor periphery showed that self-perception and real ancestry may not go hand in hand. "The results of the tests of genomic ancestry are quite different from the self made estimates of European ancestry", say the researchers. The test results showed that the proportion of European genetic ancestry was higher than students expected. When questioned before the test, students who identified as "pardos", for example, identified as 1/3 European, 1/3 African and 1/3 Amerindian.[53][54] On the other hand, students classified as "white" tended to overestimate their proportion of African and Amerindian genetic ancestry.[53]

Cuba

About one-fourth of Cubans are mulattoes. Whites have been the dominant ethnic group for centuries. Although mulattoes have become increasingly prominent since the mid-20th century, some mulattoes still face racial discrimination.[55]

Hispaniola

Mulattoes account for up to 5% of Haiti's population. In Haitian history, such mixed-race people, known in colonial times as free people of color, gained some education and property before the Revolution. In some cases, their white fathers arranged for multiracial sons to be educated in France and join the military, giving them an advance economically. Free people of color gained some social capital and political power before the Revolution, were influential during the Revolution and since then. The people of color have retained their elite position, based on education and social capital, that is apparent in the political, economic and cultural hierarchy in present-day Haiti. Numerous leaders throughout Haiti's history have been people of color.[56]

The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) was started by mulattoes.[57] The subsequent struggle within Haiti between the mulattoes led by André Rigaud and the black Haitians led by Toussaint Louverture devolved into the War of Knives.[58][59] Toussaint eventually won the conflict and made himself ruler of the entire island of Hispaniola. Napoleon ordered for Charles Leclerc and a substantial army to put down the rebellion; Leclerc seized Toussaint in 1802 and deported him to France, where he died in prison a year later. Leclerc was succeeded by General Rochambeau. With reinforcements from France and Poland, Rochambeau began a bloody campaign against the mulattoes and intensified operations against the blacks, importing bloodhounds to track and kill them. Thousands of black POW and suspects were chained to cannonballs and tossed into the sea.[60] Historians of the Haitian Revolution credit Rochambeau's brutal tactics for uniting black and mulatto soldiers against the French.

In 1806, Haiti divided into a black-controlled north and a mulatto-ruled south. Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer (1818–43), the son of a Frenchman and a former African slave, managed to unify a divided Haiti but excluded blacks from power. In 1847, a black military officer named Faustin Soulouque was made president, with the mulattoes supporting him; but, instead of proving a tool in the hands of the senators, he showed a strong will, and, although by his antecedents belonging to the mulatto party, he began to attach the blacks to his interest. The mulattoes retaliated by conspiring; but Soulouque began to decimate his enemies by confiscation, proscriptions, and executions. The black soldiers began a general massacre in Port-au-Prince, which ceased only after the French consul, Charles Reybaud, threatened to order the landing of marines from the men-of-war in the harbor.

Ambitious to unite the two parts of the island, Soulouque invaded the Dominican territory in March, 1849, but was defeated in a decisive battle by Pedro Santana near Ocoa on 21 April and compelled to retreat. Haitian strategy was ridiculed by the American press:

[At the first encounter] ... a division of negro troops of Faustin ran, and their commander, Gen. Garat, was killed. The main body, eighteen thousand troops, under the Emperor, encountered four hundred Dominicans with a field piece, and notwithstanding the disparity of force, the latter charged and caused the Haytiens to flee in every direction ... Faustin came very near falling into the enemy's hands. They were once within a few feet of him, and he was only saved by Thirlonge and other officers of his staff, several of whom lost their lives. The Dominicans pursued the retreating Haytiens some miles until they were checked and driven back by the Garde Nationale of Port-au-Prince, commanded by Robert Gateau, the auctioneer.[62]

Despite the failure of the campaign, Soulouque caused himself to be proclaimed emperor on 26 August 1849, under the name of Faustin I. Toward the close of 1855, he invaded the Dominican territory again at the head of an army of 30,000 men, but was again defeated by Santana, and barely escaped being captured. His treasure and crown fell into the hands of the enemy. Soulouque was ousted in a military coup led by mulatto General Fabre Geffrard in 1858–59.

In the eastern two-thirds of Hispaniola, the mulattoes were an ever-growing majority group, and in essence they took over the entire Dominican Republic, with no organized black opposition. The Dominican Republic has been described as the only true mulatto country in the world.[63] A pervasive Dominican racism, based on rejection of African ancestry, led to many assaults against the large Haitian immigrant community,[63] the most lethal of which was the 1937 Parsley Massacre. Approximately 5,000–67,000[64] men, women, children, babies and elderly, who were selected by their skin color, were massacred with machetes, or were thrown to sharks.[65]

Puerto Rico

In a 2002 genetic study of maternal and paternal direct lines of ancestry of 800 Puerto Ricans, 61% had mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from an Amerindian female ancestor, 27% inherited MtDNA from a female African ancestor and 12% had MtDNA from a female European ancestor.[66] Conversely, patrilineal direct lines, as indicated by the Y chromosome, showed that 70% of Puerto Rican males in the sample have Y chromosome DNA from a male European ancestor, 20% inherited Y-DNA from a male African ancestor, and less than 10% inherited Y-DNA from a male Amerindian ancestor.[67] As these tests measure only the DNA along the direct matrilineal and patrilineal lines of inheritance, they cannot tell what total percentage of European, Indigenous, or African ancestry any individual has.

In keeping with Spanish practice, for most of its colonial period, Puerto Rico had laws such as the Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar. A person with African ancestry could be considered legally white if he could prove that at least one person per generation in the last four generations had been legally white. People of black ancestry with known white lineage were classified as white, in contrast to the "one-drop rule" put into law in the early 20th century in the United States. In colonial and antebellum times in certain locations, persons of three-quarters or more white ancestry were considered legally white.[68] If born to slave mothers, however, this status did not overrule their being considered slaves, like Sally Hemings, who was three-quarters white, and her children by Thomas Jefferson, who were seven-eighths white, and all born into slavery.

United States

Colonial and Antebellum eras

Historians have documented sexual abuse of enslaved women during the colonial and post-revolutionary slavery times by white men in power: planters, their sons before marriage, overseers, etc., which resulted in many multiracial children born into slavery. Starting with Virginia in 1662, colonies adopted the principle of partus sequitur ventrem in slave law, which said that children born in the colony were born into the status of their mother. Thus, children born to slave mothers were born into slavery, regardless of who their fathers were and whether they were baptized as Christians. Children born to white mothers were free, even if they were mixed-race. Children born to free mixed-race mothers were also free.

Paul Heinegg has documented that most of the free people of color listed in the 1790–1810 censuses in the Upper South were descended from unions and marriages during the colonial period in Virginia between white women, who were free or indentured servants, and African or African-American men, servant, slave or free. In the early colonial years, such working-class people lived and worked closely together, and slavery was not as much of a racial caste. Slave law had established that children in the colony took the status of their mothers. This meant that multi-racial children born to white women were born free. The colony required them to serve lengthy indentures if the woman was not married, but nonetheless, numerous individuals with African ancestry were born free, and formed more free families. Over the decades, many of these free people of color became leaders in the African-American community; others married increasingly into the white community.[69][70] His findings have been supported by DNA studies and other contemporary researchers as well.[71]

A daughter born to a South Asian father and Irish mother in Maryland in 1680, both of whom probably came to the colony as indentured servants, was classified as a "mulatto" and sold into slavery.[72]

Historian F. James Davis says,

Rapes occurred, and many slave women were forced to submit regularly to white males or suffer harsh consequences. However, slave girls often courted a sexual relationship with the master, or another male in the family, as a way of gaining distinction among the slaves, avoiding field work, and obtaining special jobs and other favored treatment for their mixed children (Reuter, 1970:129). Sexual contacts between the races also included prostitution, adventure, concubinage, and sometimes love. In rare instances, where free blacks were concerned, there was marriage (Bennett, 1962:243–68).[73]

Historically in the American South, the term mulatto was also applied at times to persons with mixed Native American and African American ancestry.[74] For example, a 1705 Virginia statute reads as follows:

"And for clearing all manner of doubts which hereafter may happen to arise upon the construction of this act, or any other act, who shall be accounted a mulatto, Be it enacted and declared, and it is hereby enacted and declared, That the child of an Indian and the child, grand child, or great grand child, of a negro shall be deemed, accounted, held and taken to be a mulatto."[75]

But southern colonies began to prohibit Indian slavery in the eighteenth century, so, according to their own laws, even mixed-race children born to Native American women should be considered free. The societies did not always observe this distinction.

Certain Native American tribes of the Inocoplo family in Texas referred to themselves as "mulatto".[76] At one time, Florida's laws declared that a person from any number of mixed ancestries would be legally defined as a mulatto, including White/Hispanic, Black/Native American, and just about any other mix as well.[77]

In the United States, due to the influence and laws making slavery a racial caste, and later practices of hypodescent, white colonists and settlers tended to classify persons of mixed African and Native American ancestry as black, regardless of how they identified themselves, or sometimes as Black Indians. But many tribes had matrilineal kinship systems and practices of absorbing other peoples into their cultures. Multiracial children born to Native American mothers were customarily raised in her family and specific tribal culture. Federally recognized Native American tribes have insisted that identity and membership is related to culture rather than race, and that individuals brought up within tribal culture are fully members, regardless of whether they also have some European or African ancestry. Many tribes have had mixed-race members who identify primarily as members of the tribes.

If the multiracial children were born to slave women (generally of at least partial African descent), they were classified under slave law as slaves. This was to the advantage of slaveowners, as Indian slavery had been abolished. If mixed-race children were born to Native American mothers, they should be considered free, but sometimes slaveholders kept them in slavery anyway. Multiracial children born to slave mothers were generally raised within the African-American community and considered "black".[74]

Influence

Some mixed-race people in the South became wealthy enough to become slave owners themselves. At times they held family members in slavery when there were many restrictions against freeing slaves. By the time of the Civil War, many mixed-race persons, or free people of color, who were accepted in the society supported the Confederacy. For example, William Ellison owned 60 slaves. Andrew Durnford of New Orleans, which had a large population of free people of color, mostly of French descent and Catholic culture, was listed in the census as owning 77 slaves. In Louisiana free people of color constituted a third class between white colonists and the mass of slaves.[78]

Other multiracial people became abolitionists and supported the Union. Frederick Douglass escaped slavery and became nationally known as an abolitionist in the North.

In other examples, Mary Ellen Pleasant and Thomy Lafon of New Orleans used their fortunes to support the abolitionist cause. Francis E. Dumas, also a free person of color in New Orleans, emancipated all his slaves and organized them into a company in the Second Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guards.[79]

The men of color below spanned the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Contemporary era

Mulatto was used as an official census racial category in the United States, to acknowledge multiracial persons, until 1930. (In the early 20th century, several southern states had adopted the one-drop rule as law, and southern Congressmen pressed the US Census Bureau to drop the mulatto category: they wanted all persons to be classified as "black" or "white".)[80][81][82]

In the 2000 United States Census, 6,171 Americans self-identified as having mulatto ancestry.[83] Since then, persons responding to the census have been allowed to identify as having more than one type of ethnic ancestry.

Colonial references

- Fernandino

- Quadroon – and other terms denoting the degree of African descent

- Métis

- Mestizo

- Zambo

- Creole peoples

See also

- African diaspora in the Americas

- Afro-Argentines

- Afro-Colombians

- Afro-Latin Americans

- Afro-Mexicans

- Cafres

- Cassare, a marriage alliance between European traders and African rulers.

- Casta

- Cholo

- Coloureds

- Free people of color

- Melungeon

- Multiracial

- Rhineland Bastard

- Tragic mulatto

References

- Notes

- Corominas describes his doubts on the theory as follows: "[Mulato] does not derive from the Arab muwállad, 'acculturated foreigner' and sometimes 'mulatto' (see 'Mdí'), as Eguílaz would have it, since this word was pronounced 'moo-EL-led' in the Arabic of Spain. In the 19th century, Reinhart Dozy (Supplément aux Dictionnaires Arabes, Vol. II, Leyden, 1881, 841a) rejected this Arabic etymology, indicating the true one, supported by the Arabic nagîl, 'mulatto', derived from nagl, 'mule'."[13]

- In the Dominican Republic, the mulatto population absorbed remnants of the Taíno Amerindians historically present in that country, based on a 1960 census that included colour categories such as white, black, yellow, and mulatto. Since then, racial components have been dropped from the Dominican census.

- Citations

- official 2012 Census Archived 2014-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- 2010 US census p.5

- Mulatto – dictionary.com

- "mulatto, n. and adj". OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- "Chambers Dictionary of Etymology". Robert K. Barnhart. Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd. 2003. p. 684.

- Harper, Douglas. "mulatto". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Mulato". Real Academia Española. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

De mulo, en el sentido de híbrido, aplicado primero a cualquier mestizo

- Jack D. Forbes (1993). Africans and Native Americans: the language of race and the evolution of Red-Black peoples. University of Illinois Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-252-06321-3.

- David S. Goldstein; Audrey B. Thacker, eds. (2007). Complicating Constructions: Race, Ethnicity, and Hybridity in American Texts. University of Washington Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0295800745. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Izquierdo Labrado, Julio. "La esclavitud en Huelva y Palos (1570-1587)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Salloum, Habeeb. "The impact of the Arabic language and culture on English and other European languages". The Honorary Consulate of Syria. Archived from the original on 2008-06-30. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Corominas, Joan and Pascual, José A. (1981). Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico, Vol. ME-RE (4). Madrid: Editorial Gredos. ISBN 84-249-1362-0.

- Werner Sollors, Neither Black Nor White Yet Both, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 129.

- "São Tomé and Príncipe". Infoplease. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Cape Verde". Infoplease. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Angola". Infoplease. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Mozambique". Infoplease. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- results, search (2005-11-17). Not White Enough, Not Black Enough: Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community (1st ed.). Athens: Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780896802445.

- Palmer, Fileve (2015). "THROUGH A COLOURED LENS: POST-APARTHEID IDENTITY FORMATION AMONGST COLOUREDS IN KZN" (PDF). Scholarworks.iu.edu. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- Christopher, A.J. (2009). "Delineating the nation: South African censuses 1865–2007". Political Geography. 28 (2): 101–109. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.12.003. ISSN 0962-6298.

- The Griqua mission at Philippolis, 1822-1837. Schoeman, Karel. Pretoria, South Africa: Protea Book House. 2005. ISBN 978-1869190170. OCLC 61189833.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Vinson, Ben III. Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018, pp. 82-83, 86

- Undurraga Schüler, Verónica. "Españoles oscuros y mulatos blancos: Identidades múltiples y disfraces del color en el ocaso de la colonia chilena: 1778–1820,” in Historias de racismo y discriminación en Chile, ed. Rafael Gaune and Martín Lara (Santiago, 2009), 341–68

- Tavárez, David. "Legally Indian: Inquistorial Readings of Indigenous Identity in New Spain” in Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America. Eds. Andrew B. Fisher and Matthew D. O’Hara. Durham: Duke University Press 2009, (quoting AGN Mexico, Inquisition 669, no, 10m 481r-v) pp. 91-93.

- Schwaller, Robert C. (2010). "Mulata, Hija de Negro y India: Afro-Indigenous Mulatos in Early Colonial Mexico". Journal of Social History. 44 (3): 889–914. doi:10.1353/jsh.2011.0007. PMID 21853621.

- Thomas Gage's Travels in the New World (1648). J. Eric S. Thompson, ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1958, pp. 68-69.

- Twinam, Ann. "Purchasing Whiteness: Conversations on the Essence of Pardo-ness and Mulatto-ness at the End of Empire" in Imperial Subjects, p. 146.

- Twinam, "Purchasing Whiteness" p. 147.

- "CIA - The World Factbook -- Field Listing - Ethnic groups". CIA. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- "Pardo category includes Castizos, Mestizos, Caboclos, Gypsies, Eurasians, Hafus and Mulattoes". www.nacaomestica.org/. 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- "Black population becomes the majority in Brazil". En.mercopress.com. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral de; Moraes, Milene Raiol de; Ojopi, Élida B.; Perini, Jamila A.; Racciopi, Clarice; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos; Rios-Santos, Fabrício; Romano-Silva, Marco A.; Sortica, Vinicius A.; Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme; Harpending, Henry (16 February 2011). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil Is More Uniform Than Expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- Rodrigues De Moura, Ronald; Coelho, Antonio Victor Campos; De Queiroz Balbino, Valdir; Crovella, Sergio; Brandão, Lucas André Cavalcanti (2015). "Meta-analysis of Brazilian genetic admixture and comparison with other Latin America countries". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (5): 674–80. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22714. PMID 25820814.

- Gondin da Fonseca, Machado de Assis e o Hipopótamo, 6ªed, 1974.

- Saloum de Neves Manta, Fernanda; Pereira, Rui; Vianna, Romulo; Rodolfo Beuttenmüller de Araújo, Alfredo; Leite Góes Gitaí, Daniel; Aparecida da Silva, Dayse; de Vargas Wolfgramm, Eldamária; da Mota Pontes, Isabel; Ivan Aguiar, José; Ozório Moraes, Milton; Fagundes de Carvalho, Elizeu; Gusmão, Leonor; O'Rourke, Dennis (20 September 2013). "Revisiting the Genetic Ancestry of Brazilians Using Autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC 3779230. PMID 24073242.

- Lins, Tulio C.; Vieira, Rodrigo G.; Abreu, Breno S.; Grattapaglia, Dario; Pereira, Rinaldo W. (2009). "Genetic composition of Brazilian population samples based on a set of twenty-eight ancestry informative SNPs". American Journal of Human Biology. 22 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20976. PMID 19639555.

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral de; Moraes, Milene Raiol de; Ojopi, Élida B.; Perini, Jamila A.; Racciopi, Clarice; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos; Rios-Santos, Fabrício; Romano-Silva, Marco A.; Sortica, Vinicius A.; Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme; Harpending, Henry (16 February 2011). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil Is More Uniform Than Expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- "Profile of the Brazilian blood donor". Archived from the original on May 2, 2012.

- Drago, Carolina (February 24, 2011). "Nossa herança europeia" [Our European heritage] (in Portuguese). cienciahoje.org.br. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Lopes, Reinaldo José (October 5, 2009). "DNA de brasileiro é 80% europeu, indica estudo" [Brazilian DNA is 80% European, study shows] (in Portuguese). Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Lins, TC; Vieira, RG; Abreu, BS; Grattapaglia, D; Pereira, RW (2010). "Genetic composition of Brazilian population samples based on a set of twenty-eight ancestry informative SNPs". Am. J. Hum. Biol. 22 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20976. PMID 19639555.

- Lins, TC; Vieira, RG; Abreu, BS; Grattapaglia, D; Pereira, RW (2010). "Genetic composition of Brazilian population samples based on a set of twenty-eight ancestry informative SNPs". Am. J. Hum. Biol. 22 (2): 187–92. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20976. PMID 19639555.

- De Assis Poiares, L; De Sá Osorio, P; Spanhol, F. A.; Coltre, S. C.; Rodenbusch, R; Gusmão, L; Largura, A; Sandrini, F; Da Silva, C. M. (Feb 2010). "Allele frequencies of 15 STRs in a representative sample of the Brazilian population". Forensic Sci Int Genet. 4 (2): e61–3. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.05.006. PMID 20129458.

- de Assis Poiares, Lilian; de Sá Osorio, Paulo; Spanhol, Fábio Alexandre; Coltre, Sidnei César; Rodenbusch, Rodrigo; Gusmão, Leonor; Largura, Alvaro; Sandrini, Fabiano; da Silva, Cláudia Maria Dornelles (February 2010). "Allele frequencies of 15 STRs in a representative sample of the Brazilian population". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 4 (2): e61–e63. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.05.006. PMID 20129458.

- de Oliveira Godinho, Neide Maria (2008). "O impacto das migrações na constituição genética de populações Latino-Americanas" [The impact of migration on the genetic makeup of Latin American populations] (PDF) (in Portuguese). University of Brazil. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Black in Brazil: a question of identity", BBC News

- "DNA tests probe the genomic ancestry of Brazilians", Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research

- "Last stage of publication of the 2000 Census presents the definitive results, with information about the 5,507 Brazilian municipalities". Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Populaçăo residente, por cor ou raça, segundo a situaçăo do domicÌlio e os grupos de idade - Brasil" (PDF). Censo Demográfico 2000. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Sintese de Indicadores Sociais" (PDF). Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- White Americans Admixture Serving History; "The Ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA Lineages" National Library of Medicine, NIH; "Y-STR diversity and ethnic admixture in White and Mulatto Brazilian population samples" Scielo.

- "Rio de Janeiro's Black and Multiracial people carry more European ancestry in their genes than they supposed, according to research" Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, MEIO News

- Santos, RV; Fry, PH; Monteiro, S; Maio, MC; Rodrigues, JC; Bastos-Rodrigues, L; Pena, SD (2009). "Color, Race, and Genomic Ancestry in Brazil: Dialogues Between Anthropology and Genetics" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 50 (6): 787–819. doi:10.1086/644532. PMID 20614657. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- "Cuba". Britannica.

- Smucker, Glenn R. "The Upper Class". A Country Study: Haiti (Richard A. Haggerty, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 1989).

- "Jefferson on the Haitian Revolution".

- Corbett, Bob. "The Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803". Webster University.

- Smucker, Glenn R. "Toussaint Louverture". A Country Study: Haiti (Richard A. Haggerty, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 1989).

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. p. 141. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Schoenrich, Otto (1918). Santo Domingo: a Country with a Future. New York: Macmillan Company.

- Philadelphia Public Ledger, January 28, 1856.

- Keen, Benjamin; Haynes, Keith A. (2009). A History of Latin America. Cengage Learning. p. 303.

- "Parsley Massacre / El Corte - the Harvest". GlobalSecurity.org.

- Tarbox, Jeremy (2012). "Racist massacre in the Dominican pigmentocracy". Eureka Street. 22 (19): 20–21. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Martínez Cruzado, Juan C. (2002). "The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean:Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic" (PDF). Kacike (Special): 1–11. ISSN 1562-5028. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Gonzalez, Juan (2003-11-04). "Puerto Rican Gene Pool Runs Deep". Puerto Rico Herald. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Kinsbruner, Jay (1996). Not of Pure Blood. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822318423.

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 1995–2005, Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co, 1995-2005

- Dorothy Schneider, Carl J. Schneider, Slavery in America, Infobase Publishing, 2007, pp. 86–87.

- Felicia R Lee, "Family Tree’s Startling Roots", New York Times. Accessed November 3, 2013.

- Assisi, Francis C. (2005). "Indian-American Scholar Susan Koshy Probes Interracial Sex". INDOlink. Archived from the original on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Floyd James Davis, Who Is Black?: One Nation's Definition, pp. 38–39

- Miles, Tiya (2008). Ties that Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25002-4. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- General Assembly of Virginia (1823). "4th Anne Ch. IV (October 1705)". In Hening, William Waller (ed.). Statutes at Large. Philadelphia. p. 252. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "Mulato Indians". The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2013-01-07..

- Sewell, Christopher Scott; Hill, S. Pony (2011-06-01). The Indians of North Florida: From Carolina to Florida, the Story of the Survival of a Distinct American Indian Community. Backintyme. p. 19. ISBN 9780939479375. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- Joseph Conlin (2011). The American Past: A Survey of American History. Cengage Learning, p. 370. ISBN 111134339X

- Shirley Elizabeth Thompson, Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans, Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 162.

- "Introduction". Mitsawokett: A 17th Century Native American Community in Central Delaware.

- "Walter Plecker's Racist Crusade Against Virginia's Native Americans". Mitsawokett: A 17th Century Native American Settlement in Delaware. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Heite, Louise. "Introduction and statement of historical problem". Delaware's Invisible Indians. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- "Mulatto ancestry in 2000 U.S census". Census.gov. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Further reading

- Beckmann, Susan. "The mulatto of style: language in Derek Walcott's drama." Canadian Drama 6.1 (1980): 71-89. online

- McNeil, Daniel (2010). Sex and Race in the Black Atlantic: Mulatto Devils and Multiracial Messiahs. Routledge.

- Tenzer, Lawrence Raymond (1997). The Forgotten Cause of the Civil War: A New Look at the Slavery Issue. Scholars' Pub. House.

- Talty, Stephan (2003). Mulatto America: At the Crossroads of Black and White Culture: A Social History. HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

- Gatewood, Willard B. (1990). Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880-1920. Indiana University Press.

- Eguilaz y Yanguas, Leopoldo (1886). Glosario de las palabras españolas (castellanas, catalanas, gallegas, mallorquinas, portuguesas, valencianas y bascongadas), de orígen oriental (árabe, hebreo, malayo, persa y turco) (in Spanish). Granada: La Lealtad.

- Freitag, Ulrike; Clarence-Smith, William G., eds. (1997). Hadhrami Traders, Scholars and Statesmen in the Indian Ocean, 1750s-1960s. Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia. 57. Leiden: Brill. p. 392. ISBN 90-04-10771-1. Archived from the original on 2008-06-28. Retrieved 2008-07-14. Engseng Ho, an anthropologist, discusses the role of the muwallad in the region. The term muwallad, used primarily in reference to those of "mixed blood", is analyzed through ethnographic and textual information.

- Freitag, Ulrike (December 1999). "Hadhrami migration in the 19th and 20th centuries". The British-Yemeni Society. Archived from the original on 2000-07-12. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Myntti, Cynthia (1994). "Interview: Hamid al-Gadri". Yemen Update. American Institute for Yemeni Studies. 34 (44): 14–9. Archived from the original on 2008-06-18. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Williamson, Joel (1980). New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States. The Free Press.

External links

| Look up mulatto in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- A Brief History of Census “Race”

- Surprises in the Family Tree

- The Mulatto Factor in Black Family Genealogy

- Dr. David Pilgrim, "The Tragic Mulatto Myth", Jim Crow Museum, Ferris State University

- At "Race Relations", in-depth research links on Mulattoes, About.com

- Encarta's breakdown of Mulatto people (Archived 2009-11-01)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

.jpg)