Public Ledger (Philadelphia)

The Public Ledger was a daily newspaper in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, published from March 25, 1836 to January 1942. Its motto was "Virtue Liberty and Independence". For a time, it was Philadelphia's most popular newspaper, but circulation declined in the mid-1930s. It also operated a syndicate, the Ledger Syndicate, from 1915 until 1946.

First edition, March 25, 1836 | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Founder(s) | William Moseley Swain, Arunah S. Abell, Azariah H. Simmons |

| Founded | March 25, 1836 |

| Political alignment | Republican |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | January 1942 |

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

Early history

Founded by William Moseley Swain, Arunah S. Abell, and Azariah H. Simmons, and edited by Swain, the Public Ledger was the first penny paper in Philadelphia. At that time most papers sold for five cents (equal to $1.16 today) or more, a relatively high price which limited their appeal to only the reasonably well-off. Swain and Abell drew on the success of the New York Herald, one of the first penny papers and decided to use a one cent cover price to appeal to a broad audience. They mimicked the Herald's use of bold headlines to draw sales. The formula was a success and the Ledger posted a circulation of 15,000 in 1840, growing to 40,000 a decade later. To put this into perspective, the entire circulation of all newspapers in Philadelphia was estimated at only 8,000 when the Ledger was founded.[1]

The Ledger favored the abolition of slavery, and in 1838 its office was burned by a pro-slavery mob, two days after it burned the new Pennsylvania Hall (Philadelphia).[2]

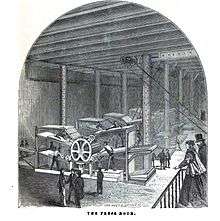

The Ledger was a technological innovator as well. It was the first daily to make use of a pony express, and among the first papers to use the electromagnetic telegraph. From 1846, it was printed on the first rotary printing press.

By the early 1860s, The Ledger was a money-losing operation, squeezed by rising paper and printing costs. It had lost circulation by supporting the Copperhead Policy of opposing the American Civil War and advocating an immediate peace settlement with the Confederate States of America. Most readers in Philadelphia at the time supported the Union, although there was a strong contingent of Southern sympathizers and families with ties to the South, as Southerners had long had second homes in Philadelphia and sent their daughters to finishing schools there. In the face of declining circulation, publishers were reluctant to increase the one-cent subscription cost, although it was needed to cover the costs of production.[3] In December 1864, the paper was sold to George William Childs and Anthony J. Drexel for a reported $20,000 (equal to $326,936 today).[4]

The Childs era

Upon buying the paper, Childs completely changed its policy and methods. He changed the editorial policy to the Loyalist (Union) line, raised advertising rates, and doubled the cover price to two cents. After an initial drop, circulation rebounded and the paper resumed profitability. Childs was closely involved in all operations of the paper, from the press room to the composing room. He intentionally upgraded the quality of advertisements appearing in the publication to suit a higher-end readership.

Childs's efforts bore fruit and the Ledger became one of the most influential journals in the country. Circulation growth led the firm to outgrow its facilities; in 1866 Childs bought property at Sixth and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia, where the Public Ledger Building was constructed. Designed by architect John McArthur, Jr., the building had at its corner a larger-than-life-sized statue of Benjamin Franklin by Joseph A. Bailly (1825–1883), which Childs had commissioned.

The quality and profitability of the Ledger improved dramatically. By 1894, The New York Times described it as "...the finest newspaper office in the country."[3] Toward the end of Child's leadership, the Ledger was estimated to generate profits of approximately $500,000 per year.

In 1870, Mark Twain mocked the Ledger for its rhyming obituaries, in a piece entitled "Post-Mortem Poetry",[5] in his column for The Galaxy:

There is an element about some poetry which is able to make even physical suffering and death cheerful things to contemplate and consummations to be desired.

The Ochs era

In 1902, Adolph Ochs, owner of The New York Times, bought the paper from Drexel's estate for a reported $2.25 million.[6] He merged it with the Philadelphia Times (which he had bought the previous year), and installed his brother George as editor. Oakes served as editor until 1914, two years after Curtis bought the publication.

The Curtis era

In 1913, Cyrus H. K. Curtis purchased the paper from Ochs for $2 million and hired his step son-in-law John Charles Martin as editor.[7] Curtis was owner of the magazines, Ladies' Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post. His intention was to establish the Ledger as Philadelphia's premier newspaper, which he achieved by buying and closing several competing papers: the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, the Philadelphia North American, and The Philadelphia Press among them. Philadelphia went from a peak of 13 papers in 1900 to seven in 1920, a time when the newspaper industry in the United States was consolidating in general.[8]

Under Curtis' ownership, the conservative appearance of the Ledger was increased: it avoided bold headlines and seldom printed photographs on the front page. Its conservative format has been compared by scholars to the Wall Street Journal or New York Times of the twentieth century.[8] Curtis built the Ledger's foreign news service and syndicated it to other papers via his Ledger Syndicate. From 1918 to 1921, former President William Howard Taft was on staff as an editorial contributor. To broaden the market, and compete against The Evening Bulletin, in 1914 Curtis began publishing the Evening Public Ledger, a bolder paper designed to appeal to a broader public.

(1924, Horace Trumbauer, architect)

The Ledger suffered by competition from an ascendant The Evening Bulletin, which under publisher William L. McLean grew in size from 12 pages in 1900 to 28 pages in 1920, and from circulation of 6,000 to a leadership position of over 500,000 readers in the same time. The Bulletin's bolder and more commercial approach attracted additional advertising, which in turn drew more readers. Advertising, which comprised only 1/3 of the Bulletin in 1900, grew to nearly 3/4 of its pages in 1920.[8] At the same time, the circulation at the Ledger stagnated.

Curtis built a new Public Ledger Building in 1924 on the same site as the old, designed in the Georgian Revival style by Horace Trumbauer.[9][10]

The paper made money in the 1920s, but saw circulation fall in half and profits disappear in the Great Depression. Some observers criticized the paper for an indistinct editorial policy which may have alienated readers. On the one hand, it endorsed reform politicians, while on the other hand, the paper was decidedly anti-labor. The paper ran anti-union advertisements during the 1919 Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America strike, but ran no pro-strike ads.[11]

Despite the circulation slump caused by the Depression, Curtis expanded by buying The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1930 for $18 million, but he did not consolidate the two franchises. When Curtis died in 1933, he was estimated to have lost $30 million on his newspaper ventures, with little to show for the investment.[8] In 1934, the Ledger was absorbed into the Inquirer, and management was assumed by John C. Martin, the son-in-law of the second Mrs. Curtis. He became General Manager of Curtis-Martin Newspapers.

The final years

On April 16, 1934, the morning and Sunday editions were merged into The Philadelphia Inquirer (also held by the heirs of Curtis). The Evening Public Ledger continued to be published independently. In 1939 John Martin was forced out of the management of the Evening Ledger, and control was assumed by Cary W. Bok, Curtis's younger grandson. Bok spent two years trying to make the paper pay, without success. In 1941, the Evening Public Ledger was sold to Robert Cresswell, formerly of the New York Herald Tribune. Mounting debts brought on a court-ordered liquidation, and the paper ceased publication in January 1942.

Controversy

"The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" and Bolshevism

On October 27 and October 28, 1919, the Public Ledger published excerpts from the first English-language translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The article was headlined "Red Bible". The paper published the excerpts from The Protocols, a text proposing the existence of a Jewish plot to take over the world, after removing all references to the purported Jewish authorship; it recast The Protocols as a Bolshevist manifesto.[12] Carl W. Ackerman, who wrote the articles, was later appointed head of the journalism department at Columbia University.

Awards

In 1931 Ledger reporter Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker received a Pulitzer Prize for correspondents for a series of articles on the Five Year Plan in the Soviet Union.[13][14]

Editors

- William M. Swain

- William Henry Fry (1844–1846)

- George Oakes

- Randolph Marshall (1918)

- Charles Munro Morrison (1930–1939, 1941)

- John McLaughlin

- Tiny Maxwell

- John Dwyer

- James S. Chambers (editor)

See also

- Charles Henry Sykes, Evening Ledger cartoonist from 1914 to 1942

- List of defunct newspapers of the United States

- General Pershing WWI casualty list

References

- Rottenberg, Dan (2006). The Man Who Made Wall Street. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780812219661. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- "(Untitled)". The Evening Post (New York, New York). May 22, 1838. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- New York Times, 3 Feb., 1894

-

Brown, John Howard (142548610X). The Cyclopaedia of American Biography: Comprising The Men And Women Of The United States Who Have Been Identified With The Growth Of The Nation. p. 11. ISBN 0-8078-2316-3. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "Post-Mortem Poetry". Twainquotes.com. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- Klein, Philip; Hoogenboom, Ari (1973). A History of Pennsylvania. Penn State Press. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- Anonymous (17 March 1930). "Again, Curtis-Martin". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- Hepp, John Henry (2003). The Middle Class City. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 9780812237238.

- Gallery, John Andrew, ed. (2004), Philadelphia Architecture: A Guide to the City (2nd ed.), Philadelphia: Foundation for Architecture, ISBN 0962290815, p.101

- Teitelman, Edward & Longstreth, Richard W. (1981), Architecture in Philadelphia: A Guide, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, ISBN 0262700212, p.31

- Klein p 546

- Jenkins, Philip (1997). Hoods and Shirts: The Extreme Right in Pennsylvania, 1925-1950. UNC Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-8078-2316-3.

- Brennan, Elizabeth A; Elizabeth C. Clarage (1999). Who's who of Pulitzer Prize winners. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 71. ISBN 9781573561112. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- Fischer, Heinz-Dietrich; Erika J. Fischer. The Pulitzer Prize archive: a history and anthology of award-winning materials in journalism, letters, and arts. Munich: Walter de Gruyter. p. 68. ISBN 9783598301704. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Public Ledger (Philadelphia). |

- University of Villanova: Falvey Library: Philadelphia's Public Ledger

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Document: Excerpts from the Public Ledger