Miguel Cabrera (painter)

Miguel Mateo Maldonado y Cabrera (1695–1768) was a Mestizo[1] painter born in Oaxaca but moved to Mexico City, the capital of Viceroyalty of New Spain.[2] During his lifetime, he was recognized as the greatest painter in all of New Spain. He created religious and secular art for the Catholic Church and wealthy patrons. His casta paintings, depicting interracial marriage among Amerindians, Spaniards and Africans, are considered among the genre's finest.[3] Cabrera's paintings range from tiny works on copper to enormous canvases and wall paintings. He also designed altarpieces and funerary monuments.[4]

Biography

Cabrera was born in Antequera, today's Oaxaca, Oaxaca, and moved to Mexico City in 1719. He may have studied under the Rodríguez Juárez brothers or José de Ibarra. Cabrera was a favorite painter of Archbishop Manuel José Rubio y Salinas, whose portrait he twice painted, and of the Jesuits, which earned him many commissions.

In 1756 he created an important analytical study of the icon of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Maravilla americana y conjunto de raras maravillas observadas con la dirección de las reglas del arte de la pintura (1756) ("American marvel and ensemble of rare wonders observed with the direction of the rules of the art of painting", often referred to in English simply as American Marvel).[5] Cabrera and a group of six other painters analyzed the painting, with scientific eyes, not religious, identifying four different substances used in the painting: "oil, tempera with agglutinates, an aguazo, and a fresco-like tempera." In Cabrera's assessment, no painter was capable of using such techniques in the eighteenth century, much less in the sixteenth century, when the image was created.[6] Cabrera was concerned that there was a proliferation of inferior copies of the painting, and let it be known that the noted seventeenth-century painter, Juan Correa, used a waxed paper template of the image, so that down to the last detail, copies were faithful to the original. Cabrera's atelier created many copies of the image, some of which were signed by Cabrera himself. He sought faithfulness to the original image but to add luster and power to the copies, some paintings had the notation "touched to the original," [Tocada a su Original] with the date.[7] In 1752 he was again permitted access to the icon of Our Lady of Guadalupe to make three copies with the aid of fellow painters, José de Alcíbar and José Bentura Arnáez. The copies were for his patron Archbishop José Manuel Rubio y Salinas, one for Pope Benedict XIV, and a third to use "as a model for further copies."[8]

The essential purpose of Maravilla Americana was to affirm the 1666 opinions of the witnesses who swore that the image of the Virgin was of a miraculous nature. However, he also elaborated a novel opinion: the image was crafted with a unique variety of techniques. He contended that the Virgin's face and hands were painted in oil paint, while her tunic, mandorla, and the cherub at her feet were all painted in egg tempera. Finally, her mantle was executed in gouache. He observed that the golden rays emanating from the Virgin seemed to be of dust that was woven into the very fabric of the canvas, which he asserted was of "a coarse weave of certain threads which we vulgarly call pita," a cloth woven from palm fibers.

His involvement in the analysis of the Guadalupe image was part of his long term campaign to raise the status of painters from mere artisans to respected practitioners of the liberal arts. It came at the same time that Mexican archbishop Manuel José Rubio y Salinas (1749-1765) sought the designation of the Virgin of Guadalupe as a universal patron. Jesuit Francisco López was the advocate in Rome for her cause. Benedict XIV recognized Guadalupe with her own feast day, starting in 1754.[9][10]

In 1753, he founded the second Academy of Painting in Mexico City and served as its director.[11]

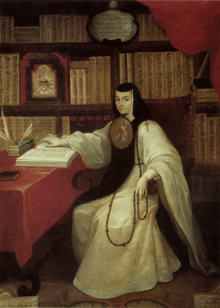

Most of the rest of his works are also religious in nature; as the official painter of the Archbishop of Mexico, Cabrera painted his and other portraits. In 1760, Cabrera created The Virgin of the Apocalypse, which describes the chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation.[12] He is also known for his posthumous portrait of the seventeenth-century poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Cabrera is currently most famous for his casta paintings. One of the sixteen in the set that was missing for many years was purchased by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2015.[3] The museum received information that the last of the sixteen, thought lost, may be in Los Angeles, California.[13]

In the 19th century, the writer José Bernardo Couto called him "the personification of the great artist and of the painter par excellence; and a century after his death the supremacy which he knew how to merit remains intact." His remains are interred at the Church of Santa Inés in Mexico City.

Gallery

Allegory of the Virgin Patroness of the Dominicans

Allegory of the Virgin Patroness of the Dominicans

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) The divine shepherdess, around 1760

The divine shepherdess, around 1760 The Adoration of the Kings

The Adoration of the Kings Don Juan Xavier Joachín Gutiérrez Altamirano Velasco, Count of Santiago de Calimaya, ca. 1752. Oil on canvas Brooklyn Museum

Don Juan Xavier Joachín Gutiérrez Altamirano Velasco, Count of Santiago de Calimaya, ca. 1752. Oil on canvas Brooklyn Museum_Cervantes_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum

Doña María de la Luz Padilla y Gómez de Cervantes, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum

Manuel José Rubio y Salinas, Chapter house - Cathedral of Mexico, oil on canvas, 1758  The Flight into Egypt

The Flight into Egypt

St. Francis Xavier

St. Francis Xavier Miguel Cabrera. St. Ignatius of Loyola

Miguel Cabrera. St. Ignatius of Loyola Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Mexican nun and savante, posthumous portrait, oil on canvas, 1750

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Mexican nun and savante, posthumous portrait, oil on canvas, 1750 The Annunciation

The Annunciation The Marriage of the Virgin

The Marriage of the Virgin

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miguel Cabrera (painter). |

- Inmaculada Rodríguez Moya (2003). La mirada del virrey: iconografía del poder en la Nueva España. Jaume I University. p. 70. ISBN 84-8021-418-X.

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. Art of Colonial Latin America. London: Phaidon Press 2005, p. 418

- "LACMA purchases long-lost masterpiece, once kept under a couch". LATimes.com. 2015-04-01. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- Bargellini, Clara. "Cabrera, Miguel." In Davíd Carrasco (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, vol 1. New York : Oxford University Press, 2001

- americanmarvel.org

- Peterson, Jeanette Favrot. Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press 2014, p. 107.

- Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe, pp. 198-99

- Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe, p. 194.

- Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe, p. 298.

- Cuadrielo, Jaime. "Zodiaco Mariano: Una alegoria de Miguel Cabrera" in Zodiaco Mariano, pp. 21-128. Mexico City: Insigne y Nacional Basilica de Santa María de Guadalupe.

- Hamnett, Brian R. A concise history of Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999: 97 (retrieved through Google Books, 1 May 2009). ISBN 978-0-521-58916-1.

- "Miguel Cabrera, Virgin of the Apocalypse – Smarthistory". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- An 18th century masterpiece appears to be hiding in L.A., Los Angeles Times 22 October 2017, front page. accessed 18 November 2017.

Further reading

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. Art of Colonial Latin America. London: Phaidon Press 2005.

- Carrillo y Gariel, Abelardo. El pintor Miguel Cabrera. México, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1966. OCLC 2900831

- Castro Mantecón, Javier; Manuel Zárate AquinoMiguel Cabrera, pintor oaxaqueño del siglo XVIII,. México, Instituto Nacional de Antropología 41579}}exas Press 1967.

- Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press 2004.

- Peterson, Jeanette Favrot. Visualizing Guadalupe. Austin: University of Texas Press 2014.

- Toussaint, Manuel. Colonial Art in Mexico. Translated and edited by Elizabeth Wilder Weisman. Austin: University of Texas Press 1967.