Apprenticeship

An apprenticeship is a system of training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in a regulated profession. Most of their training is done while working for an employer who helps the apprentices learn their trade or profession, in exchange for their continued labor for an agreed period after they have achieved measurable competencies. Apprenticeship lengths vary significantly across sectors, professions, roles and cultures. People who successfully complete an apprenticeship in some cases can reach the "journeyman" or professional certification level of competence. In others can be offered a permanent job at the company that provided the placement. Although the formal boundaries and terminology of the apprentice/journeyman/master system often do not extend outside guilds and trade unions, the concept of on-the-job training leading to competence over a period of years is found in any field of skilled labor.

Alternative terminology

There is no global consensus on a single term and depending on the culture, country and sector, the same or very similar definitions are used to describe the terms apprenticeship, internship and trainee-ship. These last two terms seem to be preferred in the health sector - examples of this being internships in medicine for physicians and trainee-ships for nurses - and anglo-saxonic countries. Apprenticeship is the preferred term of the European Commission and the one selected for use by the European Center for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP), which has developed many studies on the subject. Some of country adapt the practice from European country such as Malaysia collaborate with Germany industry to build the professional technician.

Types of apprenticeships

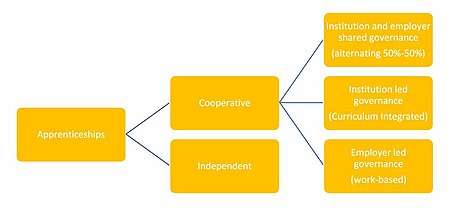

Apprenticeships can be divided into two main categories: Independent and Cooperative.[2]

Independent apprenticeships are those organized and managed by employers, without any involvement from educational institutions. They happen dissociated from any educational curricula, which means that, usually, the apprentices are not involved in any educational programme at the same time but, even if they are, there is no relation between the undergoing studies and the apprenticeship.

Cooperative apprenticeships are those organized and managed in cooperation between educational institutions and employers. They vary in terms of governance, some being more employer lead and others more educational institution lead, but they are always associated with a curriculum and are designed as a mean for students to put theory in practice and master knowledge in a way that empowers them with professional autonomy. Their main characteristics could be summarized into the following:

| Institution and Employer shared Governance | Institution led Governance (long cycle) | Institution led Governance (short cycle) | Employer led Governance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education program | ISCED 6 | ISCED 6 | ISCED 6 | ISCED 5-6 |

| Type of program | Institution- & work-integrated | Higher Vocational Education, Professional Higher Education, Higher Education | Higher Vocational Education, Professional Higher Education, Higher Education | Higher Vocational Education, Professional Higher Education |

| Average length | 3–4 years | 2–3 years | 2–3 years | 1 year |

| Balance theory/practice | Alternating theory & practice (50%-50%) | Short placements from few weeks to 6 months | Placements from 30-40% of the curriculum | Employed for a minimum of 30 hours per week, 20% of learning hours must be off-the-job |

| Location of learning | Institution -& work-integrated | Institution -& work-integrated | Institution -& work-integrated | Work-based |

| Contract | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

History

The system of apprenticeship first developed in the later Middle Ages and came to be supervised by craft guilds and town governments. A master craftsman was entitled to employ young people as an inexpensive form of labour in exchange for providing food, lodging and formal training in the craft. Most apprentices were males, but female apprentices were found in crafts such as seamstress,[3] tailor, cordwainer, baker and stationer.[4] Apprentices usually began at ten to fifteen years of age, and would live in the master craftsman's household. The contract between the craftsman, the apprentice and, generally, the apprentice's parents would often be governed by an indenture.[5] Most apprentices aspired to becoming master craftsmen themselves on completion of their contract (usually a term of seven years), but some would spend time as a journeyman and a significant proportion would never acquire their own workshop. In Coventry those completing seven-year apprenticeships with stuff merchants were entitled to become freemen of the city.[6]

Apprenticeship systems worldwide

Australia

Australian Apprenticeships encompass all apprenticeships and traineeships. They cover all industry sectors in Australia and are used to achieve both 'entry-level' and career 'upskilling' objectives. There were 475,000 Australian Apprentices in-training as at 31 March 2012, an increase of 2.4% from the previous year. Australian Government employer and employee incentives may be applicable, while State and Territory Governments may provide public funding support for the training element of the initiative. Australian Apprenticeships combine time at work with formal training and can be full-time, part-time or school-based.[7]

Australian Apprentice and Traineeship services are dedicated to promoting retention, therefore much effort is made to match applicants with the right apprenticeship or traineeship. This is done with the aid of aptitude tests, tips, and information on 'how to retain an apprentice or apprenticeship'.[8]

Information and resources on potential apprenticeship and traineeship occupations are available in over sixty industries.[9]

The distinction between the terms apprentices and trainees lies mainly around traditional trades and the time it takes to gain a qualification. The Australian government uses Australian Apprenticeships Centres to administer and facilitate Australian Apprenticeships so that funding can be disseminated to eligible businesses and apprentices and trainees and to support the whole process as it underpins the future skills of Australian industry. Australia also has a fairly unusual safety net in place for businesses and Australian Apprentices with its Group Training scheme. This is where businesses that are not able to employ the Australian Apprentice for the full period until they qualify, are able to lease or hire the Australian Apprentice from a Group Training Organisation. It is a safety net, because the Group Training Organisation is the employer and provides continuity of employment and training for the Australian Apprentice.[10][11]

In addition to a safety net, Group Training Organisations (GTO) have other benefits such as additional support for both the Host employer and the trainee/apprentice through an industry consultant who visits regularly to make sure that the trainee/apprentice are fulfilling their work and training obligations with their Host employer. There is the additional benefit of the trainee/apprentice being employed by the GTO reducing the Payroll/Superannuation and other legislative requirements on the Host employer who pays as invoiced per agreement.

Austria

Apprenticeship training in Austria is organized in a dual education system: company-based training of apprentices is complemented by compulsory attendance of a part-time vocational school for apprentices (Berufsschule).[12] It lasts two to four years – the duration varies among the 250 legally recognized apprenticeship trades.

About 40 percent of all Austrian teenagers enter apprenticeship training upon completion of compulsory education (at age 15). This number has been stable since the 1950s.[13]

The five most popular trades are: Retail Salesperson (5,000 people complete this apprenticeship per year), Clerk (3,500 / year), Car Mechanic (2,000 / year), Hairdresser (1,700 / year), Cook (1,600 / year).[14] There are many smaller trades with small numbers of apprentices, like "EDV-Systemtechniker" (Sysadmin) which is completed by fewer than 100 people a year.[15]

The Apprenticeship Leave Certificate provides the apprentice with access to two different vocational careers. On the one hand, it is a prerequisite for the admission to the Master Craftsman Exam and for qualification tests, and on the other hand it gives access to higher education via the TVE-Exam or the Higher Education Entrance Exam which are prerequisites for taking up studies at colleges, universities, "Fachhochschulen", post-secondary courses and post-secondary colleges.[12]

The person responsible for overseeing the training inside the company is called "Lehrherr" or "Ausbilder". An Ausbilder must prove that he has the professional qualifications needed to educate another person, has no criminal record and is an otherwise-respectable person. The law states that "the person wanting to educate a young apprentice must prove that he has an ethical way of living and the civic qualities of a good citizen".[16]

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic, the term "vocational school" (učiliště) can refer to the two, three or four years of secondary practical education. Apprenticeship Training is implemented under Education Act (školský zákon). Apprentices spend about 30–60% of their time in companies (sociální partneři školy) and the rest in formal education. Depending on the profession, they may work for two to three days a week in the company and then spend two or three days at a vocational school.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, after the end of compulsory schooling, two thirds of young people follow a vocational training.[17] Ninety percent of them are in the dual education system.[17]

Switzerland has an apprenticeship similarly to Germany and Austria. The educational system is ternar, which is basically dual education system with mandatory practical courses. The length of an apprenticeship can be 2, 3 or 4 years.

Length

Apprenticeships with a length of 2 years are for persons with weaker school results. The certificate awarded after successfully completing a 2-year apprenticeship is called "Attestation de formation professionnelle" (AFP) in French, "Eidgenössisches Berufsattest" (EBA) in German and "Certificato federale di formazione pratica" (CFP) in Italian. It could be translated as "Attestation of professional formation".

Apprenticeship with a length of 3 or 4 years are the most common ones. The certificate awarded after successfully completing a 3 or 4-year apprenticeship is called "Certificat Fédérale de Capacité" (CFC) in French, "Eidgenössisches Fähigkeitszeugnis" (EFZ) in German and "Attestato federale di capacità" (AFC) in Italian. It could be translated as "Federal Certificate of Proficiency".

Some crafts, such as electrician, are educated in lengths of 3 and 4 years. In this case, an Electrician with 4 years apprenticeship gets more theoretical background than one with 3 years apprenticeship. Also, but that is easily lost in translation, the profession has a different name.

Each of the over 300 nationwide defined vocational profiles has defined framework – conditions as length of education, theoretical and practical learning goals and certification conditions.

Age of the apprentices

Typically an apprenticeship is started at age of 15 and 18 after finishing general education. Some apprenticeships have a recommend or required age of 18, which obviously leads to a higher average age. There is formally no maximum age, however, for persons above 21 it is hard to find a company due to companies preferring younger ages due to the lower cost of labour.

Canada

In Canada, apprenticeships tend to be formalized for craft trades and technician level qualifications. At the completion of the provincial exam, they may write the Provincial Standard exam. British Columbia is one province that uses these exams as the provincial exam. This means a qualification for the province will satisfy the whole country. The inter-provincial exam questions are agreed upon by all provinces of the time. At the time there were only four (4) provinces, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Canada East (now Ontario), and Canada West (now Quebec).

In Canada, each province has its own apprenticeship program, which may be the only route into jobs within compulsory trades.

France

In France, apprenticeships also developed between the ninth and thirteenth centuries, with guilds structured around apprentices, journeymen and master craftsmen, continuing in this way until 1791, when the guilds were suppressed.

The first laws regarding apprenticeships were passed in 1851. From 1919, young people had to take 150 hours of theory and general lessons in their subject a year. This minimum training time rose to 360 hours a year in 1961, then 400 in 1986.

The first training centres for apprentices (centres de formation d'apprentis, CFAs) appeared in 1961, and in 1971 apprenticeships were legally made part of professional training. In 1986 the age limit for beginning an apprenticeship was raised from 20 to 25. From 1987 the range of qualifications achieveable through an apprenticeship was widened to include the brevet professionnel (certificate of vocational aptitude), the bac professionnel (vocational baccalaureate diploma), the brevet de technicien supérieur (advanced technician's certificate), engineering diplomas, master's degree and more.

On January 18, 2005, President Jacques Chirac announced the introduction of a law on a programme for social cohesion comprising the three pillars of employment, housing and equal opportunities. The French government pledged to further develop apprenticeship as a path to success at school and to employment, based on its success: in 2005, 80% of young French people who had completed an apprenticeship entered employment. In France, the term apprenticeship often denotes manual labor but it also includes other jobs like secretary, manager, engineer, shop assistant... The plan aimed to raise the number of apprentices from 365,000 in 2005 to 500,000 in 2009. To achieve this aim, the government is, for example, granting tax relief for companies when they take on apprentices. (Since 1925 a tax has been levied to pay for apprenticeships.) The minister in charge of the campaign, Jean-Louis Borloo, also hoped to improve the image of apprenticeships with an information campaign, as they are often connected with academic failure at school and an ability to grasp only practical skills and not theory. After the civil unrest end of 2005, the government, led by prime minister Dominique de Villepin, announced a new law. Dubbed "law on equality of chances", it created the First Employment Contract as well as manual apprenticeship from as early as 14 years of age. From this age, students are allowed to quit the compulsory school system in order to quickly learn a vocation. This measure has long been a policy of conservative French political parties, and was met by tough opposition from trade unions and students.

Germany

Apprenticeships are part of Germany's dual education system, and as such form an integral part of many people's working life. Finding employment without having completed an apprenticeship is almost impossible. For some particular technical university professions, such as food technology, a completed apprenticeship is often recommended; for some, such as marine engineering it may even be mandatory.

In Germany, there are 342 recognized trades (Ausbildungsberufe) where an apprenticeship can be completed. They include for example doctor's assistant, banker, dispensing optician, plumber or oven builder.[18] The dual system means that apprentices spend about 50–70% of their time in companies and the rest in formal education. Depending on the profession, they may work for three to four days a week in the company and then spend one or two days at a vocational school (Berufsschule). This is usually the case for trade and craftspeople. For other professions, usually which require more theoretical learning, the working and school times take place blockwise e.g., in a 12–18 weeks interval. These Berufsschulen have been part of the education system since the 19th century.

In 2001, two-thirds of young people aged under 22 began an apprenticeship, and 78% of them completed it, meaning that approximately 51% of all young people under 22 have completed an apprenticeship. One in three companies offered apprenticeships in 2003,[19] in 2004 the government signed a pledge with industrial unions that all companies except very small ones must take on apprentices.

The latent decrease of the German population due to low birth rates is now causing a lack of young people available to start an apprenticeship.[20][21][22][23][24]

Apprenticeship after general education

After graduation from school at the age of fifteen to nineteen (depending on type of school), students start an apprenticeship in their chosen professions. Realschule and Gymnasium graduates usually have better chances for being accepted as an apprentice for sophisticated craft professions or apprenticeships in white-collar jobs in finance or administration. An apprenticeship takes between 2.5 and 3.5 years. Originally, at the beginning of the 20th century, less than 1% of German students attended the Gymnasium (the 8–9 year university-preparatory school) to obtain the Abitur graduation which was the only way to university back then. In the 1950s still only 5% of German youngsters entered university and in 1960 only 6% did. Due to the risen social wealth and the increased demand for academic professionals in Germany, about 24% of the youngsters entered college/university in 2000.[25] Of those who did not enter university, many started an apprenticeship. The apprenticeships usually end a person's education by age 18–20, but also older apprentices are accepted by the employers under certain conditions. This is frequently the case for immigrants from countries without a compatible professional training system.

History

In 1969, a law (the Berufsbildungsgesetz) was passed which regulated and unified the vocational training system and codified the shared responsibility of the state, the unions, associations and the chambers of trade and industry. The dual system was successful in both parts of the divided Germany. In the GDR, three-quarters of the working population had completed apprenticeships.

Business and administrative professions

The precise skills and theory taught on German apprenticeships are strictly regulated. The employer is responsible for the entire education programme coordinated by the German chamber of commerce. Apprentices obtain a special apprenticeship contract until the end of the education programme. During the programme it is not allowed to assign the apprentice to regular employment and he is well protected from abrupt dismissal until the programme ends. The defined content and skill set of the apprentice profession must be fully provided and taught by the employer. The time taken is also regulated. Each profession takes a different time, usually between 24 and 36 months.

Thus, everyone who had completed an apprenticeship e.g., as an industrial manager (Industriekaufmann) has learned the same skills and has attended the same courses in procurement and stocking up, controlling, staffing, accounting procedures, production planning, terms of trade and transport logistics and various other subjects. Someone who has not taken this apprenticeship or did not pass the final examinations at the chamber of industry and commerce is not allowed to call himself an Industriekaufmann. Most job titles are legally standardized and restricted. An employment in such function in any company would require this completed degree.

Trade and craft professions

The rules and laws for the trade and craftwork apprentices such as mechanics, bakers, joiners, etc. are as strict as and even broader than for the business professions. The involved procedures, titles and traditions still strongly reflect the medieval origin of the system. Here, the average duration is about 36 months, some specialized crafts even take up to 42 months.

After completion of the dual education, e.g., a baker is allowed to call himself a bakery journeyman (Bäckergeselle). After the apprenticeship the journeyman can enter the master's school (Meisterschule) and continue his education at evening courses for 3–4 years or full-time for about one year. The graduation from the master's school leads to the title of a master craftsman (Meister) of his profession, so e.g., a bakery master is entitled as Bäckermeister. A master is officially entered in the local trade register, the craftspeople's roll (Handwerksrolle). A master craftsman is allowed to employ and to train new apprentices. In some mostly safety-related professions, e.g., that of electricians only a master is allowed to found his own company.

License for educating apprentices

To employ and to educate apprentices requires a specific license. The AdA – Ausbildung der Ausbilder – "Education of the Educators" license needs to be acquired by a training at the chamber of industry and commerce.

The masters complete this license course within their own master's coursework. The training and examination of new masters is only possible for masters who have been working several years in their profession and who have been accepted by the chambers as a trainer and examiner.

Academic professionals, e.g., engineers, seeking this license need to complete the AdA during or after their university studies, usually by a one-year evening course.

The holder of the license is only allowed to train apprentices within his own field of expertise. For example, a mechanical engineer would be able to educate industrial mechanics, but not e.g., laboratory assistants or civil builders.

After the apprenticeship of trade and craft professions

When the apprenticeship is ended, the former apprentice now is considered a journeyman. He may choose to go on his journeyman years-travels.

India

In India, the Apprentices Act was enacted in 1961.[26] It regulates the programme of training of apprentices in the industry so as to conform to the syllabi, period of training etc. as laid down by the Central Apprenticeship Council and to utilise fully the facilities available in industry for imparting practical training with a view to meeting the requirements of skilled manpower for industry.

The Apprentices Act enacted in 1961 and was implemented effectively in 1962. Initially, the Act envisaged training of trade apprentices. The Act was amended in 1973 to include training of graduate and diploma engineers as "Graduate" & "Technician" Apprentices. The Act was further amended in 1986 to bring within its purview the training of the 10+2 vocational stream as "Technician (Vocational)" Apprentices.

Responsibility of implementing Apprentices Act

Overall responsibility is with the Directorate General of Employment & Training (DGE&T) in the Union Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship.[27]

- For Trades Apprentices (ITI-Passed/Fresher) : DGE&T is also responsible for implementation of the Act in respect of Trade Apprentices in the Central Govt. Undertakings & Departments. This is done through six Regional Directorates of Apprenticeship Training located at Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Kanpur and Faridabad. While State Apprenticeship Advisers are responsible for implementation of the Act in respect of Trade Apprentices in State Government Undertakings/ Departments and Private Establishments.

- For Graduate, Technician (Polytechnic Diploma holder) and Technician (H.S Vocational-Passed) Apprentices: Department of Education in the Ministry of Human Resource Development is responsible for implementation of the through four Boards of Apprenticeship Training located at Chennai, Kanpur, Kolkata and Mumbai.[28]

Liberia

In Liberia, tailor apprenticeships engage with more skilled tailors to learn the craft and the skills that may be taught in more traditional school settings. They learn from master tailors, which gives the apprentices a promised job once their training is completed. Apprentices must have a grasp on patterns, measurement, and other math skills. They demonstrate full concept mastery before moving on to the next piece of clothing. Instead of formal testing for evaluation, articles of clothing must meet the quality standards before they can be sold and before the apprentice can begin a new design.[29]

Pakistan

In Pakistan, the Apprenticeship Training is implemented under a National Apprenticeship Ordinance 1962 and Apprenticeship Rules 1966. It regulates apprenticeship programs in industry and a TVET institute for theoretical instructions. It is obligatory for industry having fifty or more workers in an apprenticeable trade to operate apprenticeship training in the industry. Entire cost of training is borne by industry including wages to apprentices. The provincial governments through Technical Education & Vocational Training Authorities (Punjab TEVTA, Sindh TEVTA, KP TEVTA, Balochistan TEVTA and AJK TEVTA) enforce implementation of apprenticeship.

The training period varies for different trades ranging from 1–4 years. As of 2015, more than 30,000 apprentices are being trained in 2,751 industries in 276 trades across Pakistan. This figure constitutes less than 10% of institution based Vocational Training i.e. more than 350 thousand annually.

Recently, Government of Pakistan through National Vocational & Technical Training Commission (NAVTTC) has initiated to reform existing system of apprenticeship. Highlights of the modern apprenticeship system are:

- Inclusion of services, agriculture and mining sector - Cost sharing by Industry and Government - Regulating and formalizing Informal Apprenticeships - Mainstream Apprenticeship Qualifications with National Vocational Qualifications Framework (Pakistan NVQF) - Increased participation of Female - Training Cost reimbursement (for those industries training more number of apprentices than the required) - Assessment and Certification of apprentices jointly by Industry – Chamber of Commerce & Industry – Government - Apprenticeship Management Committee (having representation of 40% employers, 20% workers and 40% Government officials)

Turkey

In Turkey, apprenticeship has been part of the small business culture for centuries since the time of Seljuk Turks who claimed Anatolia as their homeland in the 11th century.

There are three levels of apprenticeship. The first level is the apprentice, i.e., the "çırak" in Turkish. The second level is pre-master which is called, "kalfa" in Turkish. The mastery level is called as "usta" and is the highest level of achievement. An 'usta' is eligible to take in and accept new 'ciraks' to train and bring them up. The training process usually starts when the small boy is of age 10–11 and becomes a full-grown master at the age of 20–25. Many years of hard work and disciplining under the authority of the master is the key to the young apprentice's education and learning process.

In Turkey today there are many vocational schools that train children to gain skills to learn a new profession. The student after graduation looks for a job at the nearest local marketplace usually under the authority of a master.

United Kingdom

Early history

Apprenticeships have a long tradition in the United Kingdom, dating back to around the 12th century and flourishing by the 14th century. The parents or guardians of a minor would agree with a master craftsman or tradesman the conditions for an apprenticeship. This contract would then bind the youth for 5–9 years (e.g., from age 14 to 21). Apprentices' families would sometimes pay a "premium" or fee to the craftsman and the contract would usually be recorded in a written indenture.[30] Modern apprenticeships range from craft to high status in professional practice in engineering, law, accounting, architecture, management consulting, and others.

In towns and cities with guilds, apprenticeship would often be subject to guild regulation, setting minimum terms of service, or limiting the number of apprentices that a master could train at any one time.[31] Guilds also often kept records of who became an apprentice, and this would often provide a qualification for later becoming a freeman of a guild or a citizen of a city.[32] Many youths would train in villages or communities that lacked guilds, however, so avoiding the impact of these regulations.

In the 16th century, the payment of a "premium" to the master was not at all common, but such fees became relatively common by the end of the 17th century, though they varied greatly from trade to trade. The payment of a one-off fee could be very difficult for some parents, limiting who was able to undertake apprenticeships. In the 18th-century, apprenticeship premiums were taxed, and the registers of the Stamp Duty that recorded tax payments mostly survive, showing that roughly one in ten teenage males served an apprenticeship for which they paid fees, and that the majority paid five to ten pounds to their master.[33]

In theory no wage had to be paid to an apprentice since the technical training was provided in return for the labour given, and wages were illegal in some cities, such as London. However, it was usual to pay small sums to apprentices, sometimes with which to buy, or instead of, new clothes. By the 18th century regular payments, at least in the last two or three years of the apprentice's term, became usual and those who lived apart from their masters were frequently paid a regular wage. This was sometimes called the "half-pay" system or "colting", payments being made weekly or monthly to the apprentice or to his parents. In these cases, the apprentice often went home from Saturday night to Monday morning. This was the norm in the 19th century but this system had existed in some trades since the 16th century.[34]

In 1563, the Statute of Artificers and Apprentices was passed to regulate and protect the apprenticeship system, forbidding anyone from practising a trade or craft without first serving a 7-year period as an apprentice to a master[35] (though in practice Freemen's sons could negotiate shorter terms).[36]

From 1601, 'parish' apprenticeships under the Elizabethan Poor Law came to be used as a way of providing for poor, illegitimate and orphaned children of both sexes alongside the regular system of skilled apprenticeships, which tended to provide for boys from slightly more affluent backgrounds. These parish apprenticeships, which could be created with the assent of two Justices of the Peace, supplied apprentices for occupations of lower status such as farm labouring, brickmaking and menial household service.[30]

Nineteenth century

In the early years of the Industrial Revolution entrepreneurs began to resist the restrictions of the apprenticeship system,[37] and a legal ruling established that the Statute of Apprentices did not apply to trades that were not in existence when it was passed in 1563, thus excluding many new 18th century industries.[34][35] In 1814 the requirement that a free worker in a skilled trade needed to have served an apprenticeship was abolished. However with the abolition of slavery, the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 established an apprenticeship system whereby formerly enslaved Africans where obliged to work three quarters of their time for their former owners. This was reckoned at 40½ hours per week.[38]

System introduced in 1964

The mainstay of training in industry has been the apprenticeship system (combining academic and practice), and the main concern has been to avoid skill shortages in traditionally skilled occupations and higher technician and engineering professionals, e.g., through the UK Industry Training Boards (ITBs) set up under the 1964 Act. The aims were to ensure an adequate supply of training at all levels; to improve the quality and quantity of training; and to share the costs of training among employers. The ITBs were empowered to publish training recommendations, which contained full details of the tasks to be learned, the syllabus to be followed, the standards to be reached and vocational courses to be followed. These were often accompanied by training manuals, which were in effect practitioners' guides to apprentice training, and some ITBs provide training in their own centres. The ITBs did much to formalise what could have been a haphazard training experience and greatly improved its quality. The years from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s saw the highest levels of apprentice recruitment, yet even so, out of a school leaving cohort of about 750,000, only about 110,000 (mostly boys) became apprentices. The apprenticeship system aimed at highly developed craft and higher technician skills for an elite minority of the workforce, the majority of whom were trained in industries that declined rapidly from 1973 onwards, and by the 1980s it was clear that in manufacturing this decline was permanent.[39]

Since the 1950s, the UK high technology industry (Aerospace, Nuclear, Oil & Gas, Automotive, Telecommunications, Power Generation and Distribution etc.) trained its higher technicians and professional engineers via the traditional indentured apprenticeship system of learning – usually a 4–6 year process from age 16–21. There were 4 types of traditional apprenticeship: craft, technician, higher technician, and graduate. Craft, technician and higher technician apprenticeships usually took 4 to 5 years while a graduate apprenticeship was a short 2-year experience usually while at university or post graduate experience. Non-graduate technician apprenticeships were often referred to as "technical apprenticeships". The traditional apprenticeship framework in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s was designed to allow young people (from 16 years old) an alternative path to A Levels to achieve both an academic qualification (equivalent to today's level 4 or 5 NVQs) and competency-based skills for knowledge work. Often referred to as the "Golden Age" of work and employment for bright young people, the traditional technical apprenticeship framework was open to young people who had a minimum of 4 GCE O-Levels to enroll in an Ordinary National Certificate or Diploma (ONC, OND) or a City & Guilds engineering technician course. Apprentices could progress to the Higher National Certificate, Higher National Diploma (HNC, HND) or advanced City and Guilds course such as Full Technological Certification. Apprenticeship positions at elite companies often had hundreds of applications for a placement. Academic learning during an apprenticeship was achieved either via block release or day release at a local technical institute. An OND or HND was usually obtained via the block release approach whereby an apprentice would be released for periods of up to 3 months to study academic courses full-time and then return to the employer for applied work experience. For entrance into the higher technical engineering apprenticeships, GCE O-Levels had to include Mathematics, Physics, and English language. The academic level of subjects such as mathematics, physics, chemistry on ONC/OND, and some City & Guilds advanced technician courses, was equivalent to A level mathematics, physics and chemistry. The academic science subjects were based on applied science in subjects such as thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, mechanics of machines, dynamics and statics, electrical science and electronics. These are often referred to as the engineering sciences. HNC and HND were broadly equivalent to subjects in the first year of a bachelor's degree in engineering but not studied to the same intensity or mathematical depth. HNC was accepted as entrance into the first year of an engineering degree and high performance on an HND course could allow a student direct entry into the second year of a degree. Few apprentices followed this path since it would have meant 10–12 years in further and higher education. For the few that did follow this path they accomplished a solid foundation of competency-based work training via apprenticeship and attained a higher academic qualification at a university or Polytechnic combining both forms of education; vocational plus academic. During the 1970s, City and Guilds assumed responsibility for the administration of HNC and HND courses.

The City and Guilds of London Institute the forerunner of Imperial College engineering school has been offering vocational education through apprenticeships since the 1870s from basic craft skills (mechanic, hairdresser, chef, plumbing, carpentry, bricklaying, etc.) all the way up to qualifications equivalent to university master's degrees and doctorates. The City and Guilds diploma of fellowship is awarded to individuals who are nationally recognised through peer review as having achieved the very highest level in competency-based achievement. The first award of FCGI was approved by Council in December 1892 and awarded in 1893 to Mr H A Humphrey, Engineering Manager of the Refined Bicarbonate and Crystal Plant Departments of Brunner, Mond & Co. His award was for material improvements in the manufacture of bicarbonate of soda. The system of nomination was administered within Imperial College, with recommendations being passed to the Council of the Institute for approval. About 500–600 people have been awarded Fellowship.

Traditional framework

The traditional apprenticeship framework's purpose was to provide a supply of young people seeking to enter work-based learning via apprenticeships by offering structured high-value learning and transferable skills and knowledge. Apprenticeship training was enabled by linking industry with local technical colleges and professional engineering institutions. The apprenticeship framework offered a clear pathway and competency outcomes that addressed the issues facing the industry sector and specific companies. This system was in place since the 1950s. The system provided young people with an alternative to staying in full-time education post- 16/18 to gain purely academic qualifications without work-based learning. The apprenticeship system of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s provided the necessary preparation for young people to qualify as a Craft trade (Machinist, Toolmaker, Fitter, Plumber, Welder, Mechanic, Millwright etc.), or Technician (quality inspector, draughtsman, designer, planner, work study, programmer), or Technician Engineer (tool design, product design, methods, stress and structural analysis, machine design etc.) and enabled a path to a fully qualified Chartered Engineer in a specific discipline (Mechanical, Electrical, Civil, Aeronautical, Chemical, Building, Structural, Manufacturing etc.). The Chartered Engineer qualification was usually achieved aged 28 and above. Apprentices undertook a variety of job roles in numerous shop floor and office technical functions to assist the work of master craftsmen, technicians, engineers, and managers in the design, development, manufacture and maintenance of products and production systems.

It was possible for apprentices to progress from national certificates and diplomas to engineering degrees if they had the aptitude.[40] The system allowed young people to find their level and still achieve milestones along the path from apprenticeship into higher education via a polytechnic or university. Though rare, it was possible for an apprentice to advance from vocational studies, to undergraduate degree, to graduate study and earn a master's degree or a PhD. The system was effective; industry was assured of a supply of practically educated and work-skilled staff, local technical colleges offered industry relevant courses that had a high measure of academic content and an apprentice was prepared for professional life or higher education by the age of 21. With the exception of advanced technology companies particularly in aerospace (BAE systems, Rolls-Royce, Bombardier) this system declined with the decline of general manufacturing industry in the UK.

Traditional apprenticeships reached their lowest point in the 1980s: by that time, training programmes declined. The exception to this was in the high technology engineering areas of aerospace, chemicals, nuclear, automotive, power and energy systems where apprentices continued to served the structured four- to five-year programmes of both practical and academic study to qualify as engineering technician or Incorporate Engineer (engineering technologist) and go on to earn a master of engineering degree and qualify as a Chartered Engineer (UK); the UK gold standard engineering qualification. Engineering technicians and technologists undertook combined theory and practice typically for example at a technical college for one day and two evenings per week on a City & Guilds programme or Ordinary National Certificate / Higher National Certificate course. Becoming a chartered engineer via the apprenticeship route normally involved 10 – 12 years of academic and vocational training at a combination of an employer, college of further education and/or university. In 1986 National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) commenced to stem a great fall in vocational training. By 1990, apprenticeship had reached an approximate low, at 2⁄3 of 1% of total employment.

Revitalisation from 1990s onward

In 1994, the UK Government introduced Modern Apprenticeships (renamed Apprenticeships in England, Wales and Northern Ireland), based on frameworks today of the Sector Skills Councils. In 2009, the National Apprenticeship Service was founded to coordinate apprenticeships in England. Apprenticeship frameworks contain a number of separately certified elements:

- a knowledge-based element, typically certified through a qualification known as a ‘Technical Certificate’ (not mandatory in the Scottish Modern Apprenticeship);

- a competence-based element, typically certified through an NVQ (in Scotland this can be through an SVQ or an alternative competence-based qualification);

- Functional Skills which are in all cases minimum levels of Mathematics and English attainment and in some cases additionally IT (in Scotland, Core Skills); and

- Employment Rights and Responsibilities (ERR) to show that the Apprentice has had a full induction to the company or training programme, and is aware of those rights and responsibilities that are essential in the workplace; this usually requires the creation of a personal portfolio of activities, reading and instruction sessions, but is not examined.

- A path with parity involving university-only education.

In Scotland, Modern Apprenticeship Frameworks are approved by the Modern Apprenticeship Group (MAG) and it, with the support of the Scottish Government, has determined that from January 2010, all Frameworks submitted to it for approval, must have the mandatory elements credit rated for the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF).

As of 2009, there are over 180 apprenticeship frameworks.[41] The current scheme extends beyond manufacturing and high technology industry to parts of the service sector with no apprenticeship tradition. In 2008, Creative & Cultural Skills, the Sector Skills Council, introduced a set of Creative Apprenticeships awarded by EDI.[42] A freelance apprenticeship framework was also approved and uses freelance professionals to mentor freelance apprentices. The Freelance Apprenticeship was first written and proposed by Karen Akroyd (Access To Music) in 2008. In 2011, Freelance Music Apprenticeships are available in music colleges in Birmingham, Manchester and London. The Department of Education under its 2007–2010 name stated their intention to make apprenticeships a "mainstream part of England's education system".[43]

Employers who offer apprenticeship places have an employment contract with their apprentices, but off-the-job training and assessment is wholly funded by the state for apprentices aged between 16–18 years. In England, Government only contributes 50% of the cost of training for apprentices aged 19–24 years. Apprenticeships at Level 3 or above for those aged 24 or over no longer receive state funding, although there is a state loan facility in place by which individuals or companies can cover the cost of study and assessment and repay the state by installments over an extended period at preferential rates of interest.

Government funding agencies (in England, the Skills Funding Agency) contract with "learning providers" to deliver apprenticeships, and may accredit them as a National Skills Academy. These organisations provide off-the-job tuition and manage the bureaucratic workload associated with the apprenticeships. Providers are usually private training companies but might also be further education colleges, voluntary sector organisations, Chambers of Commerce or employers themselves.

Structure of apprenticeships in 2000s

The UK government has implemented a rigorous apprenticeship structure which in many ways resembles the traditional architecture of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. There are three levels of apprenticeship available spanning 2–6 years of progression. It is possible for ambitious apprentices to progress from level 2 (intermediate) to level 7 ( master's degree) over many years of training and education. Learners start at a level which reflects their current qualifications and the opportunities available in the sector of interest:

Intermediate Apprenticeship (Level 2; equivalent to five good GCSE passes): provides learners with the skills and qualifications for their chosen career and allow entry (if desired) to an Advanced Apprenticeship. To be accepted learners need to be enthusiastic, keen to learn and have a reasonable standard of education; most employers require applicants to have two or more GCSEs (A*-C), including English and Maths.[44]

Advanced Apprenticeship (Level 3; equivalent to two A-level passes): to start this programme, learners should have five GCSEs (grade A*-C) or have completed an Intermediate Apprenticeship. This will provide them with the skills and qualifications needed for their career and allow entry (if desired) to a Higher Apprenticeship or degree level qualification. Advanced apprenticeships can last between two and four years.[45]

Higher Apprenticeship (Level 4/5; equivalent to a Foundation Degree): to start this programme, learners should have a Level 3 qualification (A-Levels, Advanced Diploma or International Baccalaureate) or have completed an Advanced Apprenticeship. Higher apprenticeships are designed for students who are aged 18 or over.[46]

Degree Apprenticeship (Level 5/6; achieve bachelor's degree) and (Level 7 Masters): to start this programme, learners should have a level 3/4 qualification (A-Levels, Advanced Diploma or International Baccalaureate) relevant to occupation or have completed an Advanced Apprenticeship also relevant to occupation. It differs from a 'Higher Apprenticeship' due to graduating with a bachelor's degree at an accredited university. Degree apprenticeships can last between two and four years.[47]

Under the current UK system, commencing from 2013, groups of employers ('trailblazers') develop new apprenticeships, working together to design apprenticeship standards and assessment approaches.[48] As at July 2015, there were 140 Trailblazer employer groups which had so far collectively delivered or were in the process of delivering over 350 apprenticeship standards.[49][50]

In industries where self-employment or unpaid employment are the typical form of work, an "alternative English apprenticeship" may be used (in England). Alternative English apprenticeships also operate where an apprentice has been made redundant but continues with their training although not in a paid apprenticeship position, and for elite athletes training with a view to competing in the Olympics, Paralympics or Commonwealth Games.[51] This form of apprenticeship is regulated by the Apprenticeships (Alternative English Completion Conditions) Regulations 2012.[52] Apprentices who have been made redundant but continue with their training must complete their apprenticeship within six months of their redundancy.

From April 2017 an Apprenticeship Levy has been in place to fund apprenticeships. Many UK public bodies are subject to a statutory target to employ an average of at least 2.3% of their staff as new start apprentices over the period from 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2021, and to "have regard" to this target when planning their recruitment and career development activities.[53]

United States

Apprenticeship programs in the United States are regulated by the Smith–Hughes Act (1917), The National Industrial Recovery Act (1933), and National Apprenticeship Act, also known as the "Fitzgerald Act."[54]

The number of American apprentices has increased from 375,000 in 2014 to 500,000 in 2016, while the federal government intends to see 750,000 by 2019, particularly by expanding the apprenticeship model to include white-collar occupations such as information technology.[55][56]

Educational regime

- See also standards based education reform which eliminates different standards for vocational or academic tracks

In the United States, education officials and nonprofit organizations who seek to emulate the apprenticeship system in other nations have created school to work education reforms. They seek to link academic education to careers. Some programs include job shadowing, watching a real worker for a short period of time, or actually spending significant time at a job at no or reduced pay that would otherwise be spent in academic classes or working at a local business. Some legislators raised the issue of child labor laws for unpaid labor or jobs with hazards.

In the United States, school to work programs usually occur only in high school. American high schools were introduced in the early 20th century to educate students of all ability and interests in one learning community rather than prepare a small number for college. Traditionally, American students are tracked within a wide choice of courses based on ability, with vocational courses (such as auto repair and carpentry) tending to be at the lower end of academic ability and trigonometry and pre-calculus at the upper end.

American education reformers have sought to end such tracking, which is seen as a barrier to opportunity. By contrast, the system studied by the NCEE (National Center on Education and the Economy) actually relies much more heavily on tracking. Education officials in the U.S., based largely on school redesign proposals by NCEE and other organizations, have chosen to use criterion-referenced tests that define one high standard that must be achieved by all students to receive a uniform diploma. American education policy under the "No Child Left Behind Act" has as an official goal the elimination of the achievement gap between populations. This has often led to the need for remedial classes in college.[57]

Many U.S. states now require passing a high school graduation examination to ensure that students across all ethnic, gender and income groups possess the same skills. In states such as Washington, critics have questioned whether this ensures success for all or just creates massive failure (as only half of all 10th graders have demonstrated they can meet the standards).[58]

The construction industry is perhaps the heaviest user of apprenticeship programs in the United States, with the US Department of Labor reporting 74,164 new apprentices accepted in 2007 at the height of the construction boom. Most of these apprentices participated in what are called "joint" apprenticeship programs, administered jointly by construction employers and construction labor unions.[59] For example, the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades (IUPAT) has opened the Finishing Trades Institute (FTI). The FTI is working towards national accreditation so that it may offer associate and bachelor's degrees that integrate academics with a more traditional apprentice programs. The IUPAT has joined forces with the Professional Decorative Painters Association (PDPA) to build educational standards using a model of apprenticeship created by the PDPA.

Examples of programs

Persons interested in learning to become electricians can join one of several apprenticeship programs offered jointly by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and the National Electrical Contractors Association. No background in electrical work is required. A minimum age of 18 is required. There is no maximum age. Men and women are equally invited to participate. The organization in charge of the program is called the National Joint Apprenticeship and Training Committee .

Apprentice electricians work 32 to 40+ hours per week at the trade under the supervision of a journeyman wireman and receive pay and benefits. They spend an additional 8 hours every other week in classroom training. At the conclusion of training (five years for inside wireman and outside lineman, less for telecommunications), apprentices reach the level of journeyman wireman. All of this is offered at no charge, except for the cost of books (which is approximately $200–600 per year), depending on grades. Persons completing this program are considered highly skilled by employers and command high pay and benefits. Other unions such as the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, United Association of Plumbers, Fitters, Welders and HVAC Service Techs, Operating Engineers, Ironworkers, Sheet Metal Workers, Plasterers, Bricklayers and others offer similar programs.

Trade associations such as the Independent Electrical Contractors and Associated Builders and Contractors also offer a variety of apprentice training programs. Eight registered programs also are offered by the Aerospace Joint Apprenticeship Committee (AJAC) to fill a shortage of aerospace and advanced manufacturing workers in Washington State, including occupations such as machinist, tool and die maker, industrial maintenance technician and registered Youth Apprenticeships.

For FDA-regulated industries such as food, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, nutraceuticals and cosemecuticals, companies may offer apprenticeships in Quality Assurance, Quality Control, Medical Affairs (MSLs), Clinical Trials, or Regulatory Affairs. Apprentices may be placed at a host company and must continue to work toward an industry certification such as those offered by ASQ or RAPS while they remain in the apprenticeship. The costs of training and mentorship can be covered by the program and apprentices receive full pay and benefits.

Example of a professional apprenticeship

A modified form of apprenticeship is required for before an engineer is licensed as a Professional Engineer in the United States. In the United States, each of the 50 states sets its own licensing requirements and issues licenses to those who wish to practice engineering in that state.

Although the requirements can vary slightly from state to state, in general to obtain a Professional Engineering License, one must graduate with Bachelor of Science in Engineering from an accredited college or university, pass the Fundamentals of Engineering (FE) Exam, which designates the title of Engineer in Training (EIT), work in that discipline for at least four years under a licensed Professional Engineer (PE), and then pass the Principles and Practice of Engineering Exam. One and two years of experience credit is given for those with qualifying master’s and doctoral degrees, respectively.[60]

In most cases the states have reciprocity agreements so that once an individual becomes licensed in one state can also become licensed in other states with relative ease.

Youth Apprenticeship

Youth Apprenticeship is promising new strategy to engage youth in career connected learning, encourage high school completion, lower the youth unemployment rate, lower the skills gap and to provide a pipeline for youth into higher education or into industry as qualified workers to fill open positions.

These programs provide high school sophomores, juniors, and seniors with a career and educational pathway into industry. They develop real-world skills, earn competitive wages, and gain high school credits towards graduation and receive tuition free college credits. Upon completion of the program, the youth apprentices will obtain a journey level certification from the State Department of Labor and Industries, a nationally recognized credential.

Youth apprenticeship has been successfully piloted in a number of states including, Washington, Wisconsin, Colorado, Oregon, North Carolina and South Carolina. In these states, thousands of high school students engage in both classroom technical training and paid structured on-the-job training across a number of high-growth, high-demand industries. In Charlotte, NC several companies, many rooted in Europe, have started joint programs (Apprenticeship Charlotte and Apprenticeship 2000) to jointly further the idea of apprenticeships and close the gap in technical workforce availability. In Washington State, the Aerospace Joint Apprenticeship Committee has partnered with nearly 50 aerospace manufacturing companies to offer registered Youth Apprenticeships in partnership with the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries.

Re-entry Apprenticeship

Apprenticeship programs for individuals who have been previously incarcerated aim to decrease recidivism and increase re-entry employment.[61] The Post-Release Employment Project cross analyzed data of inmates who utilized re-entry apprenticeship programs amongst those who did not. It has been found that post-prison programs increase an ex-inmate's likelihood to retain employment. Participation in work and job skill programs decreased an inmates likelihood of being recommitted by 8 to 12 years.[62] The three main types of re-entry apprenticeship programs are: "jobs in the prison setting, short term vocation training in prison, and short term assistance in the job search process upon release."[63] Research done by Uggan in 2000, concluded that these programs have the greatest effects on individuals older than 26 years old.[63] Andrews et al., highlights the importance of catering prison programs to the needs of a specific offender. Not everyone will benefit equally from these programs and this form of training has found to only be beneficial to for those who are ready to exit crime.[63] An example of a re-entry apprenticeship program is Job Corps. Job Corps is a residential program centered around work, providing a structured community for at-risk teens. In 2000, an experiment done by Schochet et al., found that those who were not enrolled in the program were had an arrest rate 15.9% higher than those who were enrolled in the program.[63]

White-Collar Apprenticeships

The U.S. Department of Labor has identified a model that has been successful in Europe and transferred it to American corporations, the model of white-collar apprenticeship programs. These programs are similar to other, more traditional blue-collar apprenticeship programs as they both consist of on-the-job training as the U.S. Department of Labor has implemented a path for the middle class in America to learn the necessary skills in a proven training program that employers in industries such as information technology, insurance, and health care. Through the adoption of these new white-collar apprenticeship programs, individuals are able to receive specialized training that they may have previously never been able to gain access to and, in some cases, also receive their Associate's Degree in a related field of study, sponsored by the company they are working for. [64] The desire for more apprenticeship programs and more apprenticeship training has been in bipartisan agreement, and the agreement and push for more individuals to join these programs has seen dividends for active enrollment. The Labor Department has seen an increase in the amount of active apprentices, with the number rising from 375,000 in 2013 all the way to 633,625 active apprentices in 2019; however, a majority of these active apprentices are still in areas of skilled trades, such as plumbing or electrical work, there has been a rise of over 700 new white-collar apprenticeship programs from 2017 to 2019. [65] The corporate support that these white-collar apprenticeship programs are receiving are from some of the world's largest organizations such as Amazon, CVS Health, Accenture, Aon, and many others.

Analogues at universities and professional development

The modern concept of an internship is similar to an apprenticeship but not as rigorous. Universities still use apprenticeship schemes in their production of scholars: bachelors are promoted to masters and then produce a thesis under the oversight of a supervisor before the corporate body of the university recognises the achievement of the standard of a doctorate. Another view of this system is of graduate students in the role of apprentices, post-doctoral fellows as journeymen, and professors as masters . In the "Wealth of Nations" Adam Smith states that:

Seven years seem anciently to have been, all over Europe, the usual term established for the duration of apprenticeships in the greater part of incorporated trades. All such incorporations were anciently called universities, which indeed is the proper Latin name for any incorporation whatever. The university of smiths, the university of tailors, etc., are expressions which we commonly meet with in the old charters of ancient towns [...] As to have wrought seven years under a master properly qualified was necessary in order to entitle any person to become a master, and to have himself apprenticed in a common trade; so to have studied seven years under a master properly qualified was necessary to entitle him to become a master, teacher, or doctor (words anciently synonymous) in the liberal arts, and to have scholars or apprentices (words likewise originally synonymous) to study under him.[66]

Also similar to apprenticeships are the professional development arrangements for new graduates in the professions of accountancy, engineering, management consulting, and the law. A British example was training contracts known as 'articles of clerkship'. The learning curve in modern professional service firms, such as law firms, consultancies or accountancies, generally resembles the traditional master-apprentice model: the newcomer to the firm is assigned to one or several more experienced colleagues (ideally partners in the firm) and learns his skills on the job.

See also

- Apprenticeship levy

- Apprentices mobility

- Apprenticeship in freemasonry

- Education

- Educational theory of apprenticeship

- German model

- Guild

- Guru-disciple tradition

- Internship

- Indentured servant

- Journeyman

- Mentorship

- Nonuniversal theory

- School-to-work transition

- Traineeship

- Tradesman

- Vocational education

References

- "Mainstreaming Procedures for Quality Apprenticeships in Educational Organisations and Enterprises (ApprenticeshipQ)".

- Davy, N., Frakenberg, A. (2019). Typology of Apprenticeships in Higher Vocational Education. Retrieved 8 May 2019

- "Apprenticeship indenture". Cambridge University Library Archives (Luard 179/9). March 18, 1642.

- "Apprenticeship indentures 1604–1697". Cambridge St Edward Parish Church archives (KP28/14/2). Archived from the original on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (2001). "The Early Middle Ages". The Oxford History of Britain. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 126.

- Adrian Room, ‘Cash, John (1822–1880)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- "Australian Apprenticeships Homepage". www.australianapprenticeships.gov.au. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- "Tips on Retaining Your Apprentice or Apprenticeship".

- "Australian Apprenticeships and Traineeships Information Service".

- "Australian Apprenticeships".

- "MEGT Australia – Apprenticeships, Traineeships, Recruitment". MEGT (Australia) Ltd.

- "Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung: Aktuelles". Archived from the original on 2009-12-17. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-07-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- STATISTIK AUSTRIA. "Bildung".

- http://www.berufslexikon.at/pdf/beruf_pdf.php?id=114&berufstyp=1%5B%5D

- Antrag auf Anerkennung als Lehrherr und Lehrbetrieb in der Landwritschaft; Land- und forstwirtschaftliche Fachausabildungsstelle Vorarlberg

- (in French) Catherine Dubouloz, "La Suisse, pays de l’apprentissage", Le temps, 27 December 2016 (page visited on 20 October 2018).

- Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (Germany). "BMWi – Ausbildungsberufe". german language. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- "Apprenticeships in the German System" (PDF). Apprenticeships in the German System.

- Meinhold, Hans-Peter; training, Lufthansa's head of vocational. "The Secret To Germany's Low Youth Unemployment". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Subscribe to read | Financial Times". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Morath, Eric. "Germany's Apprentice Challenge: Finding Young Applicants". WSJ. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Can Apprenticeships Help Reduce Youth Unemployment?". Atavist. 2015-11-15. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Apprenticeships go begging in Germany | DW | 14.06.2016". DW.COM. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Andreas Hadjar, Rolf Becker: "Die Bildungsexpansion: Erwartete und unerwartete Folgen. 2006. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; p. 32/33

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2009-05-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Apprenticeship Training Scheme (ATS) Archived October 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Home Page :: Directorate General of Training (DGT)". Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-08-21.

- Lave, Jean (1988). The Culture of Acquisition and the Practice of Understanding. Institute for Research Learning. pp. 310–326.

- Aldrich, Richard (2005) [1997 in A. Heikkinen and R. Sultana (eds), Vocational Education and Apprenticeships in Europe]. "13 – Apprenticeships in England". Lessons from History of Education. Routledge. pp. 195–205. ISBN 978-0-415-35892-7. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- Wallis, Patrick (September 2008). "Apprenticeship and Training in Premodern England" (PDF). Journal of Economic History. 68 (3): 832–861. doi:10.1017/S002205070800065X – via https://www.cambridge.org/core/.

- Withington, Phil (2005). The Politics of Commonwealth: Citizens and Freemen in Early Modern England. Cambridge. pp. 29–30.

- Minns, Chris; Wallis, Patrick (July 2013). "The price of human capital in a pre-industrial economy: Premiums and apprenticeship contracts in 18th century England". Explorations in Economic History. 50 (3): 335–350. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2013.02.001.

- "Apprenticeship in England – Learn – FamilySearch.org".

- "Research, education & online exhibitions > Family history > In depth guide to family history > People at work > Apprentices". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- Dunlop, O. J. (1912). "iv". English Apprenticeship and Child Labour, a History. London: Fisher Unwin.

- Langford, Paul (1984) [1984]. "7 – The Eighteenth Century". In Kenneth O. Morgan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain. Oxford: OUP. p. 382. ISBN 978-0-19-822684-0.

- Folz, Sebastian. "Plantation Owners and Apprenticeship: The Dawn of Emancipation". Emancipation: The Caribbean Experience. University of Miami. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Peter Haxby and David Parkes. "Apprenticeship in the United Kingdom: From ITBs to YTS". European Journal of Education, Vol. 24, No. 2 (1989), pp. 167–181.

- Peter Whalley, "The social production of technical work: the case of British engineers", SUNY Press 1986.

- "What can I do an apprenticeship in?". NGTU. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- "Creative Apprenticeships". Creative & Cultural Skills. Archived from the original on 2012-08-15.

- World Class Apprenticeships. The Government’s strategy for the future of Apprenticeships in England. DIUS/DCSF, 2008

- RateMyApprenticeship, 'Intermediate Apprenticeships' "Intermediate Apprenticeships". Retrieved 2016-12-12. accessed 12 December 2016

- RateMyApprenticeship, 'Advanced Apprenticeships' "Advanced Apprenticeships". Retrieved 2016-11-23. accessed 23 November 2016

- RateMyApprenticeship, 'Higher Apprenticeships' "Higher Apprenticeships". Retrieved 2016-11-23. accessed 23 November 2016

- RateMyApprenticeship, 'Degree Apprenticeships' "Degree Apprenticeships". Retrieved 2016-11-23. accessed 23 November 2016

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills and Department for Education, 'Future of apprenticeships in England: guidance for trailblazers', accessed 17 September 2015

- UK Government, 'The Future of Apprenticeships in England' "How to develop an apprenticeship standard: Guide for trailblazers" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-10. Retrieved 2015-08-12. accessed 17 September 2015

- Paragon Skills, 'Apprenticeships' "Apprenticeship training provider". Retrieved 2019-01-29. accessed 01 January 2019

- ESP Group (2020), Apprentices, accessed 8 August 2020

- UK Legislation, The Apprenticeships (Alternative English Completion Conditions) Regulations 2012, SI 2012/1199, accessed 8 August 2020

- Public sector apprenticeship targets, accessed 21 April 2017

- "UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR". U.S. Department of Labor.

- Krupnick, Matt (27 September 2016). "U.S. quietly works to expand apprenticeships to fill white-collar jobs: With other countries' systems as a model, apprenticeships have started to expand". Hechinger Report. Teachers College at Columbia University. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Salvador Rodriguez (2017-04-11). "As Trump Stifles Immigration, Expect Tech to Turn to Apprenticeships". Inc.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2016-02-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) SAISD Fundamental Beliefs: Excellence and equity in student performance are achievable for all students.

- Seattle Times Archived October 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, September 09, 2006 "WASL results show strong gains, puzzling declines across the state" By Linda Shaw

- "The Construction Chart Book: The US Construction Industry and its Workers" (PDF). CPWR. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "NCEES: Students". NCEES. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01.

- Saylor, William (1997). "Training Inmates Through Industrial Work Participation and Vocational Work and Apprenticeship Instruction" (PDF). www.bop.gov.

- Saylor, William (1997). "Training Inmates Through Industrial Work and Participation and Vocational and Apprenticeship Instruction" (PDF). www.bop.gov.

- Bushway, Shawn (2003). "Employment Dimensions of Reentry" (PDF). www.urban.org. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- College, Harper. "Apprenticeship Programs: Earn and Learn". www.harperapprenticeships.org.

- Stockman, Farah. "Want a White-Collar Career Without College Debt? Become an Apprentice". www.nytimes.com.

- Smith, Adam (1776). Wealth of Nations: An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell. ISBN 9781607781738.

Further reading

- Modern Apprenticeships: the way to work, The Report of the Modern Apprenticeship Advisory Committee, 2001

- Apprenticeship in the British "Training Market", Paul Ryan and Lorna Unwin, University of Cambridge and University of Leicester, 2001

- Creating a ‘Modern Apprenticeship’: a critique of the UK’s multi-sector, social inclusion approach Alison Fuller and Lorna Unwin, 2003 (pdf)

- Apprenticeship systems in England and Germany: decline and survival. Thomas Deissinger in: Towards a history of vocational education and training (VET) in Europe in a comparative perspective, 2002 (pdf)

- European vocational training systems: the theoretical context of historical development. Wolf-Dietrich Greinert, 2002 in Towards a history of vocational education and training (VET) in Europe in a comparative perspective. (pdf)

- Apprenticeships in the UK- their design, development and implementation, Miranda E Pye, Keith C Pye, Dr Emma Wisby, Sector Skills Development Agency, 2004 (pdf)

- L’apprentissage a changé, c’est le moment d’y penser !, Ministère de l’emploi, du travail et de la cohésion sociale, 2005

- Learning on the Shop Floor: Historical Perspectives on Apprenticeship, Bert De Munck, Steven L. Kaplan, Hugo Soly. Berghahn Books, 2007. (Preview on Google books)

- "The social production of technical work: the case of British engineers" Peter Whalley, SUNY Press 1986.

- "Apprenticeship in the ‘golden age’: were youth transitions really smooth and unproblematic back then?", Sarah A.Vickerstaff, University of Kent, UK, 2003

- "The Higher Apprenticeship (HA) in Engineering Technology"; The Sector Skills Council for Science, Engineering and Manufacturing technologies, UK, 2008