Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island.[3] It is located in Narragansett Bay approximately 33 miles (53 km) southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, 20 miles (32 km) south of Fall River, Massachusetts, 74 miles (119 km) south of Boston, and 180 miles (290 km) northeast of New York City. It is known as a New England summer resort and is famous for its historic mansions and its rich sailing history. It was the location of the first U.S. Open tournaments in both tennis and golf, as well as every challenge to the America's Cup between 1930 and 1983. It is also the home of Salve Regina University and Naval Station Newport, which houses the United States Naval War College, the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, and an important Navy training center. It was a major 18th-century port city and also contains a high number of buildings from the Colonial era.[4]

Newport, Rhode Island | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): City by the Sea, Sailing Capital of the World, Queen of Summer Resorts, America's Society Capital | |

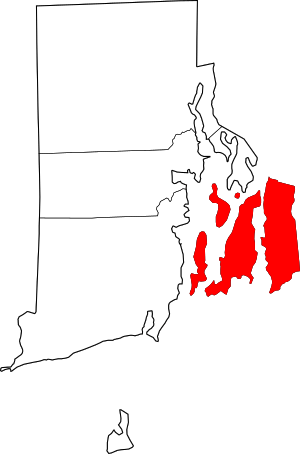

Location of Newport in Newport County, Rhode Island | |

| Coordinates: 41°29′17″N 71°18′45″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Rhode Island |

| County | Newport |

| Incorporated (city) | 1784 |

| Incorporated (town) | 1639 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jamie Bova |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.38 sq mi (29.47 km2) |

| • Land | 7.66 sq mi (19.84 km2) |

| • Water | 3.72 sq mi (9.63 km2) |

| Elevation | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 24,672 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 24,334 |

| • Density | 3,177.18/sq mi (1,226.76/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 02840-02841 |

| Area code(s) | 401 |

| FIPS code | 44-49960 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1217986 |

| Website | www |

The city is the county seat of Newport County, which has no governmental functions other than court administrative and sheriff corrections boundaries. It was known for being the location of the "Summer White Houses" during the administrations of Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy. The population was 24,672 as of 2010.

History

Colonial period

.jpg)

Newport was founded in 1639 on Aquidneck Island, which was called Rhode Island at the time. Its eight founders and first officers were Nicholas Easton, William Coddington, John Clarke, John Coggeshall, William Brenton, Jeremy Clark, Thomas Hazard, and Henry Bull. Many of these people had been part of the settlement at Portsmouth, along with Anne Hutchinson and her followers. They separated within a year of that settlement, however, and Coddington and others began the settlement of Newport on the southern side of the island.

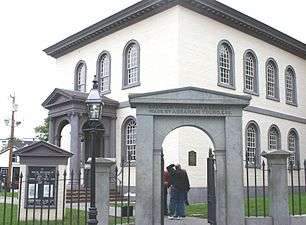

Newport grew to be the largest of the four original settlements which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, which also included Providence Plantations and Shawomett. Many of the first colonists in Newport became Baptists, and the second Baptist congregation in Rhode Island was formed in 1640 under the leadership of John Clarke. In 1658, a group of Jews were welcomed to settle in Newport; they were fleeing the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal but had not been permitted to settle elsewhere. The Newport congregation is now referred to as Congregation Jeshuat Israel and is the second-oldest Jewish congregation in the United States. It meets in Touro Synagogue, the oldest synagogue in the United States.

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations received its royal charter in 1663, and Benedict Arnold was elected as its first governor at Newport. The Old Colony House served as a seat of Rhode Island's government upon its completion in 1741 at the head of Washington Square, until the current Rhode Island State House in Providence was completed in 1904 and Providence became the state's sole capital city. Newport became the most important port in colonial Rhode Island, and a public school was established in 1640.

The commercial activity which raised Newport to its fame as a rich port was begun by a second wave of Portuguese Jews who settled there around the middle of the 18th century. They had been practicing Judaism in secret for 300 years in Portugal, and they were attracted to Rhode Island because of the freedom of worship there. They brought with them commercial experience and connections, capital, and a spirit of enterprise. Most prominent among those were Jacob Rodrigues Rivera, who arrived in 1745 (died 1789) and Aaron Lopez, who came in 1752 (died May 28, 1782). Rivera introduced the manufacture of sperm oil which became one of Newport's leading industries and made the town rich. Newport developed 17 manufactories of oil and candles and enjoyed a practical monopoly of this trade until the American Revolution.

Aaron Lopez is credited with making Newport an important center of trade.[5] He encouraged 40 Portuguese Jewish families to settle there, and Newport had 150 vessels engaged in trade within 14 years of his activity.[6] He was involved in the slave trade and manufactured spermaceti candles, ships, barrels, rum, chocolate, textiles, clothes, shoes, hats, and bottles.[7] He became the wealthiest man in Newport but was denied citizenship on religious grounds, even though British law protected the rights of Jews to become citizens.[8] He appealed to the Rhode Island legislature for redress and was refused with this ruling: "Inasmuch as the said Aaron Lopez hath declared himself by religion a Jew, this Assembly doth not admit himself nor any other of that religion to the full freedom of this Colony. So that the said Aaron Lopez nor any other of said religion is not liable to be chosen into any office in this colony nor allowed to give vote as a free man in choosing others."[9] Lopez persisted by applying for citizenship in Massachusetts, where it was granted.[10]

From the mid-17th century, the religious tolerance in Newport attracted numbers of Quakers, known also as the Society of Friends.[11] The Great Friends Meeting House in Newport (1699) is the oldest existing structure of worship in Rhode Island.

In 1727, James Franklin (brother of Benjamin) printed the Rhode-Island Almanack in Newport. In 1732, he published the first newspaper, the Rhode Island Gazette. In 1758, his son James founded the weekly newspaper Mercury. The famous 18th century Goddard and Townsend furniture was also made in Newport.

Throughout the 18th century, Newport suffered from an imbalance of trade with the largest colonial ports. As a result, Newport merchants were forced to develop alternatives to conventional exports.[12] In the 1720s, Colonial leaders arrested many pirates, acting under pressure from the British government. Many were hanged in Newport and were buried on Goat Island.

Slave trade

Newport was a major center of the slave trade in colonial and early America, active in the "triangle trade" in which slave-produced sugar and molasses from the Caribbean were carried to Rhode Island and distilled into rum, which was then carried to West Africa and exchanged for captives. In 1764, Rhode Island had about 30 rum distilleries, 22 in Newport alone. The Common Burial Ground on Farewell Street was where most of the slaves were buried.

Sixty percent of slave-trading voyages launched from North America issued from tiny Rhode Island, in some years more than 90%, and many from Newport. Almost half were trafficked illegally, breaking a 1787 state law prohibiting residents of the state from trading in slaves. Slave traders were also breaking federal statutes of 1794 and 1800 barring Americans from carrying slaves to ports outside the United States, as well as the 1807 Congressional act abolishing the transatlantic slave trade. A few Rhode Island families made substantial fortunes in the trade. William and Samuel Vernon were Newport merchants who later played an important role in financing the creation of the United States Navy; they sponsored 30 African slaving ventures. However, it was the DeWolfs of Bristol, Rhode Island, and most notably James De Wolf, who were the largest slave-trading family in all of North America, mounting more than 80 transatlantic voyages, most of them illegal. The Rhode Island slave trade was broadly based. Seven hundred Rhode Islanders owned or captained slave ships, including most substantial merchants, and many ordinary shopkeepers and tradesmen who purchased shares in slaving voyages.[13]

In addition to being one of America's most active slave ports, Newport was also home to a small community of abolitionists and free blacks. Reverend Samuel Hopkins, minister at Newport's First Congregational Church, has been called "America's first abolitionist".[14] Among subscribers to Hopkins' writings were 17 free black subscribers, most of whom lived in Newport.[14] This community of free blacks, including Newport Gardner, founded the Free African Union Society in 1780, the first African mutual aid society in America.[15]

Some of the historic buildings in Newport, near the coast

Some of the historic buildings in Newport, near the coast- Oliver Perry Monument in Eisenhower Park

Touro Synagogue, America's oldest existing synagogue

Touro Synagogue, America's oldest existing synagogue

American Revolutionary era

Newport was the scene of much activity during the American Revolution. William Ellery came from Newport, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He later served on the Naval Committee.

In the winter of 1775 and 1776, the Rhode Island Legislature put militia General William West in charge of rooting out loyalists in Newport, and several notable individuals were exiled to the northern part of the state, such as Joseph Wanton and Thomas Vernon.[16] In the fall of 1776, the British saw that Newport could be used as a naval base to attack New York (which they had recently occupied), so they took over the city. The population of Newport had divided loyalties. Many pro–independence Patriots left town, while loyalist Tories remained. Newport was a British stronghold for the next three years.

In the summer of 1778, the Americans began the campaign known as the Battle of Rhode Island. This was the first joint operation between the Americans and the French after the signing of the Treaty of Alliance. The Americans based in Tiverton planned a formal siege of the town. However, the French refused to take part in it, wanting a frontal assault. This weakened the American position, and the British were able to expel the Americans from the island. The following year, the British abandoned Newport, wanting to concentrate their forces in New York.

On July 10, 1780, a French expedition arrived in Narragansett Bay off Newport with an army of 450 officers and 5,300 men, sent by King Louis XVI and commanded by Rochambeau. For the rest of the war, Newport was the base of the French forces in the United States. In July 1781, Rochambeau was finally able to leave Newport for Providence to begin the decisive march to Yorktown, Virginia, along with General George Washington. The first Roman Catholic mass in Rhode Island was said in Newport during this time. The Rochambeau Monument in King Park on Wellington Avenue along Newport Harbor commemorates Rochambeau's contributions to the Revolutionary War and to Newport's history.

Newport's population had fallen from over 9,000 (according to the census of 1774) to fewer than 4,000 by the time that the war ended (1783). Over 200 abandoned buildings were torn down in the 1780s. Also, the war destroyed Newport's economic wealth, as years of military occupation closed the city to any form of trade. The Newport merchants moved away, some to Providence, others to Boston and New York.

It was in Newport that the Rhode Island General Assembly voted to ratify the Constitution in 1790 and become the 13th state, acting under pressure from the merchant community of Providence.

The city was the last residence of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and the birthplace of Commodore Matthew C. Perry and the Unitarian theologian William Ellery Channing.

- Rochambeau statue in King park

- Newport's City Hall

Gilded Age

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, wealthy southern planters seeking to escape the heat began to build summer cottages on Bellevue Avenue, such as Kingscote (1839).[17] Around the middle of the century, wealthy Yankees, such as the Wetmore family, also began constructing larger mansions, such as Chateau-sur-Mer (1852) nearby.[18] Most of these early families made a substantial part of their fortunes in the Old China Trade.[19]

By the turn of the 20th century, many of the nation's wealthiest families were summering in Newport, including the Vanderbilts, Astors, and the Widener family, who constructed the largest "cottages", such as The Breakers (1895) and Miramar.[20] They resided for a brief summer social season in grand, gilded mansions with elaborate receiving rooms, dining rooms, music rooms, and ballrooms—but with few bedrooms, since the guests were expected to have "cottages" of their own. Many of the homes were designed by New York architect Richard Morris Hunt, who kept a house in Newport himself.

The social scene at Newport is described in Edith Wharton's novel The Age of Innocence. Wharton's own Newport "cottage" was called Land's End. Today, many mansions continue in private use. Hammersmith Farm is the mansion where John F. Kennedy and Jackie Kennedy held their wedding reception; it was open to tourists as a "house museum", but has since been purchased and reconverted into a private residence. Many other mansions are open to tourists; still others were converted into academic buildings for Salve Regina College in the 1930s, when the owners could no longer afford their tax bills.

In the mid-19th century, a large number of Irish immigrants settled in Newport. The Fifth Ward of Newport in the southern part of the city became a staunch Irish neighborhood for many generations. To this day, St. Patrick's Day is an important day of pride and celebration in Newport, with a large parade going down Thames Street.

The oldest Catholic parish in Rhode Island is St. Mary's, located on Spring Street—though the current building is not the original one.

The Breakers, 2009

The Breakers, 2009 "Hypotenuse", Newport home owned by architect Richard Morris Hunt

"Hypotenuse", Newport home owned by architect Richard Morris Hunt

20th century and beyond

Rhode Island did not have a fixed capital during and after the colonial era but rotated its legislative sessions among Providence, Newport, Bristol, East Greenwich, and South Kingstown. In 1854, the sessions were eliminated in the cities other than Providence and Newport, and Newport was finally dropped in 1900. A constitutional amendment that year restricted the meetings of the legislature to Providence.[21]

John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier were married in St. Mary's Church in Newport on September 12, 1953.[22] Presidents Kennedy and Eisenhower both made Newport the sites of their "Summer White Houses" during their years in office. Eisenhower stayed at Quarters A at the Naval War College and at what became known as the Eisenhower House,[23] while Kennedy used Hammersmith Farm next door.

The city has long been entwined with the United States Navy. It held the campus of the U.S. Naval Academy during the American Civil War (1861–65) when the undergraduate officer training school was temporarily moved north from Annapolis, Maryland. From 1952 to 1973, it hosted the Cruiser-Destroyer Force of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, and subsequently it has hosted smaller numbers of warships from time to time. Today it hosts the Naval Station Newport (NAVSTA Newport) and remains home to the U.S. Naval War College and the Naval Education and Training Command (NETC), the center for Surface Warfare Officer training, numerous other schools, and the headquarters of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center. The decommissioned aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-60) was moored in an inactive status at the docks previously used by the Cruiser-Destroyer Force, until it was towed to Brownsville, Texas in August–September 2014 to be dismantled. The USS Forrestal (CV-59) shared the pier until June 2010.

The departure of the Cruiser-Destroyer fleet from Newport and the closure of nearby Naval Air Station Quonset Point in 1973 were devastating to the local economy. The population of Newport decreased, businesses closed, and property values plummeted. However, in the late 1960s, the city began revitalizing the downtown area with the construction of America's Cup Avenue, malls of stores and condominiums, and upscale hotels. Construction was completed on the Newport Bridge. The Preservation Society of Newport County began opening Newport's historic mansions to the public, and the tourist industry became Newport's primary commercial enterprise over the subsequent years.[24]

Geography and climate

Newport is located at 41°29′17″N 71°18′45″W. It is the most populous municipality on Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 11.4 square miles (29.5 km2), of which 7.7 square miles (19.9 km2) is land and 3.7 square miles (9.6 km2), or 32.64%, is water.[25] The Newport Bridge, the longest suspension bridge in New England, connects Newport to neighboring Conanicut Island across the East Passage of the Narragansett.

| Climate data for Newport, Rhode Island | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38 (3) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

54 (12) |

64 (18) |

72 (22) |

78 (26) |

77 (25) |

71 (22) |

62 (17) |

52 (11) |

43 (6) |

58 (15) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

31 (−1) |

39 (4) |

48 (9) |

58 (14) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

58 (14) |

48 (9) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

44 (6) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.21 (107) |

3.54 (90) |

4.53 (115) |

4.29 (109) |

3.50 (89) |

3.11 (79) |

2.99 (76) |

3.70 (94) |

3.58 (91) |

3.70 (94) |

4.49 (114) |

4.43 (113) |

46.07 (1,171) |

| Source: Newport climate | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 6,716 | — | |

| 1800 | 6,739 | 0.3% | |

| 1810 | 7,907 | 17.3% | |

| 1820 | 7,319 | −7.4% | |

| 1830 | 8,010 | 9.4% | |

| 1840 | 8,333 | 4.0% | |

| 1850 | 9,563 | 14.8% | |

| 1860 | 10,508 | 9.9% | |

| 1870 | 12,521 | 19.2% | |

| 1880 | 15,693 | 25.3% | |

| 1890 | 19,457 | 24.0% | |

| 1900 | 22,441 | 15.3% | |

| 1910 | 27,149 | 21.0% | |

| 1920 | 30,255 | 11.4% | |

| 1930 | 27,612 | −8.7% | |

| 1940 | 30,532 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 37,564 | 23.0% | |

| 1960 | 47,049 | 25.3% | |

| 1970 | 34,562 | −26.5% | |

| 1980 | 29,259 | −15.3% | |

| 1990 | 28,227 | −3.5% | |

| 2000 | 26,475 | −6.2% | |

| 2010 | 24,672 | −6.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 24,334 | [2] | −1.4% |

As of 2013, there were 24,027 people, 10,616 households, and 4,933 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,204.2 people per square mile (1,239.8/km²). There were 13,069 housing units at an average density of 1,697.3 per square mile (656.7/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 82.5% White, 6.9% African American, 0.8% Native American, 1.4% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.1% some other race, and 5.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.4% of the population (3.3% Puerto Rican, 1.2% Guatemalan, 1.1% Mexican[27]).[28]

There were 10,616 households, out of which 21.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 30.9% were headed by married couples living together, 12.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 53.5% were non-families. 41.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.7% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.05, and the average family size was 2.82.[28]

The age distribution was 16.5% under the age of 18, 16.3% from 18 to 24, 28.1% from 25 to 44, 24.9% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.3 males.[28]

For the period 2009–11, the estimated median annual income for a household in the city was $59,388, and the median income for a family was $83,880. Male full-time workers had a median income of $52,221 versus $41,679 for females. The per capita income for the city was $35,644. About 10.7% of the population were below the poverty line.[29]

Culture

Newport has one of the highest concentrations of colonial homes in the nation in the downtown Newport Historic District, one of three National Historic Landmark Districts in the city, and Newport's colonial heritage is well preserved and documented at the Newport Historical Society. In addition to the colonial architecture, the city is known for its Gilded Age mansions, summer "cottages" built in varying styles copied from the royal palaces of Europe.

The White Horse Tavern was built prior to 1673 and is one of the oldest taverns in the US.[30] Newport is also home to the Touro Synagogue, one of the oldest Jewish houses of worship in the Western hemisphere, and to the Newport Public Library and Redwood Library and Athenaeum, one of the nation's oldest lending libraries.

Bellevue Avenue's Belcourt is owned by Carolyn Rafaelian

Bellevue Avenue's Belcourt is owned by Carolyn Rafaelian Marble House, owned and operated by the Preservation Society

Marble House, owned and operated by the Preservation Society

Outdoor activities

Newport is sometimes referred to as the "Sailing Capital of the World".[31][32] The city was chosen as the new home of the National Sailing Hall of Fame which moved here from Annapolis, Maryland in 2019.[33] Several sailing clubs are based in the city, including the New York Yacht Club and the Ida Lewis Yacht Club.[34] Newport was the site of the America's Cup races from 1930 to 1983, and it remains the starting point of the biannual 635 nautical-mile Newport Bermuda Race.[35][36]

Aquidneck Island has many beaches, both public and private. The largest public beach is Easton's beach or First Beach, which has a view of the Newport Cliff Walk. Sachuest Beach or Second Beach in Middletown is the second-largest beach in the area. Gooseberry Beach is private but is open to the public on certain days of the year; it is located on Ocean Drive, along with the private Bailey's Beach and Hazard's Beach. The Cliff Walk is one of the most popular attractions in the city. It is a 3.5-mile (5.6 km) public access walkway bordering the shoreline and has been designated a National Recreation Trail.

Brenton Point State Park is the site of the annual Brenton Point Kite Festival. Newport is also home to the Newport Country Club, which hosted the 2007 Women's US Open and the 1995 Men's US Amateurs. Fort Adams dates back to the War of 1812; it houses the Museum of Yachting and hosts both the Newport Folk Festival and the Newport Jazz Festival. The Jazz Festival was established in 1954 by local socialite Elaine Lorillard and music promoter George Wein. It was held annually until 1971, and was re-established in Newport in 1981.[37][38] In 1959, Wein, folk singer Pete Seeger, and music manager Albert Grossman established the Newport Folk Festival as a counterpart to the Jazz Festival.[39] It was held in Newport through 1969, returned to the city in 1985, and has been held annually at Fort Adams since then.[39] The Folk Festival was the venue for a controversial performance by singer-songwriter Bob Dylan in July 1965 that proved influential to the "folk rock movement".[40][41] Both festivals were held at other venues in Newport before moving to Fort Adams when they were revived in the 1980s.[42][39]

As of Fall 2013, Newport has been designated a Bronze Bicycle Friendly Community by the League of American Bicyclists.[43] The International Tennis Hall of Fame is also located in Newport. The Campbell's Hall of Fame Tennis Championships is held every year in early July, the week following Wimbledon. The week also includes annual enshrinements into the Hall of Fame. The annual Citizens Bank Pell Bridge Run is held every Fall to raise money for local charities.[44]

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Newport Public Schools operates public schools: Claiborne Pell Elementary School, Thompson Middle School, Rogers High School, Newport Area Career and Technical Center, Aquidneck Island Adult Learning Center. Prior to 2013 multiple small public elementary schools served the Newport community; the Pell School, a consolidation of those schools, opened in 2013.[45]

There is one private elementary school in Newport, St. Michael's Country Day School.[46] Nearby private primary schools include All Saints Academy in Middletown, The Pennfield School in Portsmouth, and St. Philomena School in Portsmouth.[47] Nearby private secondary schools include Portsmouth Abbey School in Portsmouth and St. George's School in Middletown.

St. Joseph of Cluny School was formerly located in Newport, on property given by the estate of Arthur Curtiss James to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Providence in 1941. Military families from Fort Adams requested a Catholic school; Cluny opened in September 1957 as a kindergarten and added grades until 1965, when the first eighth grade graduation was held.[48] Since the period, the overall population of Newport declined and the concentration of the middle class declined; much of the housing became too expensive for families with young children, and there were relatively few houses being sold in Newport to new residents. In addition many families previously going to Cluny instead sent their children to the Portsmouth School Department.[47] From circa 2014 to 2017 the enrollment decreased by one fourth; the school administration stated that this decline and the general competition among private schools in the Newport area caused the operation of the school to be no longer viable. It closed in 2017.[49] Betsy Sherman Walker of Newport This Week described the closure as a "curveball" unexpected by the community.[47]

Tertiary education

Post-secondary schools include the Naval Academy Preparatory School, Salve Regina University, Naval War College, International Yacht Restoration School, and the Community College of Rhode Island Newport Campus.

Economy

Principal employers

According to Newport's 2016 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[50] the principal employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Naval Station Newport | 4,219 |

| 2 | Newport Hospital | 926 |

| 3 | City of Newport | 924 |

| 4 | Newport Harbor Corporation | 622 |

| 5 | Salve Regina University | 580 |

| 6 | Preservation Society of Newport County | 366 |

| 7 | James L. Maher Center | 344 |

| 8 | Savings Institute Bank & Trust | 315 |

| 9 | Gurney's Newport Resort and Marina | 313 |

| 10 | Newport Marriott | 225 |

Notable people

Sister cities

.svg.png)

In popular culture

Newport was a filming location for High Society (1956), The Great Gatsby (1974), Mr. North (1988), Wind (1992), and Moonrise Kingdom (2012).[51]

See also

- Buildings and structures in Newport, Rhode Island

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Aquidneck Island was called Rhode Island during Colonial times, and is still shown on nautical charts as Rhode Island. in Newport County, Rhode Island.

- James D. Kornwolf, Georgiana Wallis Kornwolf, Architecture and town planning in colonial North America, Volume 1 (JHU Press, 2002), pg. 1021 https://books.google.com/books?id=DA9_v6Ma1a8C&source=gbs_navlinks_s Archived 2015-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Settlement of the Jews in North America. Charles P. Daly, Ll.D., President of the American Geographical Society; P. Cowen, 1893, Digitized Mar 17, 2008>

- Wiernik, Peter. History of the Jews in America: From the Period of the Discovery of the New World to the Present Time. The Jewish Press Publishing Company, 1912, p. 73.

- Kaplan, Marilyn (2004), "The Jewish Merchants of Newport, 1749–1790", in George M. Goodwin and Ellen Smith (eds.), The Jews of Rhode Island, Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press ISBN 1-58465-424-4

- Feldberg, Michael (ed.) (2002). "Aaron Lopez's Struggle for Citizenship". Blessings of Freedom: Chapters in American Jewish History. New York: American Jewish Historical Society. ISBN 0-88125-756-7.

- Archived March 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Newport". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-06. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- "Great Friends Meeting House". www.newporthistory.org. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Tunnell, Daniel L.; Hechtlinger, Adelaide (April 1975). "Life in Newport Part II: The Eighteenth Century". Early American Life: 26–31.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved 2016-03-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Stokes, Keith (19 December 2017). "R.I.'s former slaves achieved great things". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Stokes, Keith. "The Black Origins of the Back to Africa Movement". 1696 Heritage Group. 1696 Heritage Group. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Vernon, Thomas; Rider, Sidney Smith; Ellery, Harrison; Greene, George Sears (1879). The Diary of Thomas Vernon. S.S. Rider. p. 1.

thomas vernon.

- "Kingscote". The Preservation Society of Newport County. Archived from the original on 2007-02-04. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- "Chateau-sur-Mer". The Preservation Society of Newport County. Archived from the original on 2007-02-04. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- Michie, Thomas (1995-04-01). "Newport and the Far East. (Newport, Rhode Island)". The Magazine Antiques. Archived from the original on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- "The Breakers". The Preservation Society of Newport County. Archived from the original on 2007-02-04. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- Taylor, William Harrison. Legislative History and Souvenir of Rhode Island, 1899–1900. pg 211

- Catherine, Martha; Anderson, Cosgrove (2005). John F. Kennedy. Learner Publishing Group. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780822526438.

- "The Eisenhower House". Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "Rhode Island History". Rhode Island General Assembly. Archived from the original on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Newport city, Rhode Island". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "QT-P10 Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Newport city, Rhode Island". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2009-2011 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates (DP03): Newport city, Rhode Island". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- "History—The White Horse Tavern". Archived from the original on 2007-01-15. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- Bessinger, Tony. "Is San Diego the Sailing Capital of the World?". Sailing World. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Sailing Capital of the World". WindCheck Magazine. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Duca, Rob (12 September 2019). "National Sailing Hall Projects 2021 Opening". Newport This Week. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Harbour Court - New York Yacht Club". nyyc.org. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "History of the America's Cup". www.americascup.com. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "About". Newport Bermuda Race. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Elaine Lorillard; helped start Newport Jazz Festival". The Boston Globe. December 3, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- Clendinen, Dudley (1981-08-24). "After a decade, prospering Newport celebrates the jazz festival's return". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- Gillis, James. "LOOKING BACK: Newport festival and folk music have come a long way since '59". The Newport Daily News. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "The Night Bob Dylan Went Electric". Time. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Righthand, Jess. "July 25, 1965: Dylan Goes Electric at the Newport Folk Festival". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "America's first jazz festival comes home". UPI. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2017-06-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Pell Bridge Run". pellbridgerun.com. Archived from the original on 2018-12-16. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- Borg, Linda (2018-02-24). "Newport's newest school already bursting at the seams". Providence Journal. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- Home. St. Michael's Country Day School. Retrieved on June 4, 2018. "ST MICHAEL’S COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL 180 Rhode Island Avenue Newport, RI 02840"

- Walker, Betsy Sherman (2017-03-09). "Navigating the Curveball of Cluny School Closing". Newport This Week. Island Communications. Archived from the original on 2018-06-04. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- Belmore, Ryan (2017-03-01). "Cluny School to Close After 60 Years (Updated)". What's Up Newp. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- Glavin, Kirsten (2017-03-02). "Newport elementary school to close at end of academic year". WLNE-TV ABC 6. Archived from the original on 2018-06-04. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "City of Newport CAFR". Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Barth, Jack (1991). Roadside Hollywood: The Movie Lover's State-By-State Guide to Film Locations, Celebrity Hangouts, Celluloid Tourist Attractions, and More. Contemporary Books. Pages 256-257. ISBN 9780809243266.

Further reading

- Bridenbaugh, Carl. Cities in the Wilderness-The First Century of Urban Life in America 1625-1742 (1938) online edition

- Bridenbaugh, Carl. Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America, 1743-1776 (1955)

- Crane, Elaine Forman. A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 1992)

- Crane, Elaine Forman. The Poison Plot: A Tale of Adultery and Murder in Colonial Newport. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018)

- Crane, Elaine F. "’The first wheel of commerce’: Newport, Rhode Island and the slave trade, 1760–1776." Slavery and Abolition (1980) 1#2 pp: 178–198.

- Downing, Antoinette Forrester, and Vincent Joseph Scully. The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island: 1640-1915 (CN Potter, 1967)

- Jefferys, C. P. B. Newport: A Short History (1992)

- Withey, Lynne. Urban growth in colonial Rhode Island: Newport and providence in the eighteenth century (SUNY Press, 1984)

Older titles

- S. G. Arnold, History of the State of Rhode Island, (two volumes, New York, (1859–60)

- G. C. Mason, Reminiscences of Newport, (Newport, 1884)

- E. M. Stone, Our French Allies, (Providence, 1884)

- Newport History, the journal of the Newport Historical Society

- Newport Mansions: Postcards of the Gilded Age, Schiffer Publishing

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Newport, Rhode Island. |

- City of Newport official website

- Discover Newport, official tourism website

- "Class and Leisure at America's First Resort: Newport 1870–1914" from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.