Sterling submachine gun

The Sterling submachine gun is a British submachine gun. It was tested with the British Army in 1944–1945 as a replacement for the Sten but it did not start to replace it until 1953. A successful and reliable design, it remained as standard issue with the British Army until 1994, when it was phased out as the L85A1 assault rifle was phased in.

| Sterling submachine gun | |

|---|---|

Sterling L2A3 (Mark 4) submachine gun | |

| Type | Submachine gun |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1944—present |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars |

|

| Production history | |

| Designer | George William Patchett |

| Designed | 1944 |

| Manufacturer | Sterling Armaments Company |

| Produced | 1953—1988 |

| No. built | 400,000+ |

| Variants | See Variants |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2.7 kilograms (6.0 lb) |

| Length | 686 millimetres (27.0 in) Folded stock: 481 millimetres (18.9 in) |

| Barrel length | 196 millimetres (7.7 in) |

| Cartridge | 9×19mm Parabellum 7.62×51mm NATO (Battle Rifle variant) |

| Action | API Blowback Lever-delayed blowback (Battle Rifle variant) |

| Rate of fire | 550 round/min |

| Effective firing range | 200 metres (220 yd) Suppressed: 50–100 metres (55–109 yd) |

| Feed system | 34-round box magazine or 32- or 50-round box magazine from the Sten and Lanchester (Patchett Machine Carbine) |

| Sights | Iron sights |

History

In 1944, the British General Staff issued a specification for a new submachine gun. It stated that the weapon should weigh no more than six pounds (2.7 kg), should fire 9×19mm Parabellum ammunition, have a rate of fire of no more than 500 rounds per minute and be sufficiently accurate to allow five consecutive shots (fired in semi-automatic mode) to be placed inside a one-foot-square target at a distance of 100 yd (91 m).

To meet the new requirement, George William Patchett, the chief designer at the Sterling Armaments Company of Dagenham, submitted a sample weapon of new design in early 1944.[17] The first Patchett prototype gun was similar to the Sten insofar as its cocking handle (and the slot it moved back and forth in) was placed in line of sight with the ejection port[18] though it was redesigned soon afterwards and moved up to a slightly offset position.[19] The army quickly recognised the Patchett's potential (i.e. significantly increased accuracy and reliability when compared with the Sten) and ordered 120 examples for trials. Towards the end of the Second World War, some of these trial samples were used in combat by airborne troops during the battle of Arnhem[20] and by special forces at other locations in Northern Europe[21] where it was officially known as the Patchett Machine Carbine Mk 1.[22] For example, a Patchett submachine gun (serial numbered 078 and now held by the Imperial War Museum), was carried in action by Colonel Robert W.P. Dawson[23] while he was Commanding Officer of No. 4 Commando, during the attack on Walcheren as part of Operation Infatuate in November 1944.[24] Because the Patchett/Sterling can use straight Sten submachine gun magazines as well as the curved Sterling design, there were no interoperability problems.

After the war, with large numbers of Sten guns in the inventory, there was little interest in replacing them with a superior design. However, in 1947, a competitive trial between the Patchett, an Enfield design, a new BSA design and an experimental Australian design was held, with the Sten for comparison. The trial was inconclusive but was followed by further development and more trials. Eventually, the Patchett design won and the decision was made in 1951 for the British Army to adopt it.[25] It started to replace the Sten in 1953 as the "Sub-Machine Gun L2A1". Its last non-suppressed variation was the L2A3 but the model changes were minimal throughout its development life.

It has made numerous appearances in the James Bond franchise.

Sterling submachine guns with minor cosmetic alterations were used in the production of the Star Wars films as Stormtrooper blaster rifle props.[26]

Design details

The Sterling submachine gun is constructed entirely of steel and plastic and has a shoulder stock, which folds underneath the weapon. There is an adjustable rear-sight, which can be flipped between 100 and 200 yard settings. Although of conventional blowback design firing from an open bolt, there are some unusual features: for example, the bolt has helical grooves cut into the surface to remove dirt and fouling from the inside of the receiver to increase reliability. There are two concentric recoil springs which cycle the bolt, as opposed to the single spring arrangement used by many other SMG designs. This double-spring arrangement significantly reduces "bolt-bounce" when cartridges are chambered, resulting in better obturation, smoother recoil and increased accuracy. Additionally, the Sterling uses a much-improved (over the Sten) 34-round curved double-column feed box magazine, which is inserted into the left side of the receiver. The magazine follower, which pushes the cartridges into the feed port, is equipped with rollers to reduce friction. The bolt feeds ammunition alternately from the top and bottom of the magazine lips, and its fixed firing pin is designed so that it does not line up with the primer in the cartridge until the cartridge has entered the chamber.[27]

The Sterling employs a degree of what is known as Advanced Primer Ignition, in that the cartridge is fired while the bolt is still moving forward, a fraction of a second before the round is fully chambered. The firing of the round thus not only sends the bullet flying down the barrel but simultaneously resists the forwards movement of the bolt. By this means it is possible to employ a lighter bolt than if the cartridge was fired after the bolt had already stopped, as in simple blowback, since the energy of the expanding gases would then only have to overcome the bolt's static inertia (plus spring resistance) to push it backwards again and cycle the weapon; whereas in this arrangement some of this energy is used up in counteracting the bolt's forwards momentum as well; and thus the bolt does not have to be so massive. The lighter bolt makes not only for a lighter gun, but a more controllable one since there is less mass moving to and fro within it as it fires.[28]

The suppressed version of the Sterling (L34A1/Mk.5) was developed for covert operations. This version uses a ported barrel surrounded by a cylinder with expansion chambers. The Australian and New Zealand SAS regiments used the suppressed version of the Sterling during the Vietnam War.[29] It is notable for having been used by both Argentinian and British Special Forces during the Falklands War.[30] A Sterling was used by Libyan agents to kill WPC Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan Embassy in London, which sparked the 1984 siege of the building.

The Sterling has a reputation for excellent reliability under adverse conditions and, even though it fires from an open bolt, good accuracy. With some practice, it is very accurate when fired in short bursts. While it has been reported that the weapon poses no problems for left-handed users to operate,[31] it is not recommended without the wearing of ballistic eye protection. The path of the ejected cartridge cases is slightly down and backward, so mild burns can occasionally be incurred by left-handed shooters.

A bayonet of a similar design as that for the L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle was produced and issued in British Army service, but was rarely employed except for ceremonial duties. Both bayonets were derived from the version issued with the Rifle No. 5 Mk I "Jungle Carbine", the main difference being a smaller ring on the SLR bayonet to fit the rifle's muzzle. When mounted, the Sterling bayonet was offset to the left of the weapon's vertical line, which gave a more natural balance when used for bayonet-fighting.

For a right-handed shooter, the correct position for the left hand while firing is on the ventilated barrel-casing, but not on the magazine, as the pressure from holding the magazine can increase the risk of stoppages, and a loose magazine can lead to dropping the weapon. The barrel-casing hold provides greater control of the weapon, so the right hand can intermittently be used for other tasks. A semi-circular protrusion on the right-hand side of the weapon, approximately two inches from the muzzle, serves to prevent the supporting hand from moving too far forward and over the muzzle.

Manufacture

A total of over 400,000 were manufactured between 1953 and 1988. Sterling built them at their factory in Dagenham for the British armed forces and for overseas sales, whilst the Royal Ordnance Factories at Fazakerley near Liverpool constructed them exclusively for the British military. Production ceased in 1988 with the closing of Sterling Armaments[32] by British Aerospace/Royal Ordnance. ROF no longer makes full weapons, but still manufactures spare parts for certified end users.

A Chilean variant was made by FAMAE as the PAF submachine gun but was different externally as it had a shorter receiver lacking the barrel shroud.[33]

Canada also manufactured a variant under license, called the Submachine Gun 9 mm C1 made by Canadian Arsenals Limited.[34] It's made from stamped metal instead of cast metal and is capable of handling a C1 bayonet, which is only used during public exhibition events and not for combat operations.[35]

A similar weapon, the Sub-Machine Gun Carbine 9 mm 1A1, is manufactured under license by the Indian Ordnance Factory at Kanpur in 1963,[36] along with a Sub-Machine Gun Carbine 9 mm 2A1, manufactured in 1977.[36] In 2012, it's reported that 5,000 SMGs were made in India.[37]

Variants

- British Armed Forces

- Unassigned: Patchett Machine Carbine Mark 1 (trials commenced in 1944)

- Unassigned: Patchett Machine Carbine Mark 1 & Folding Bayonet (same as above but with folding bayonet, never accepted)

- L2A1: (Patchett Machine Carbine Mark 2) Adopted in 1953.

- L2A2: (Sterling Mark 3) Adopted in 1955.

- L2A3: (Sterling Mark 4) Adopted in 1956. Last regular version in service with the British Army, Royal Marines and RAF Regiment.

- L34A1: Suppressed version (Sterling-Patchett Mark 5).

- Sterling Mark 6 "Police": a semi-automatic-only closed-bolt version for police forces and private sales. A US export version had a longer barrel (16 in (410 mm)) to comply with Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATF) regulations. Beginning in 2009, Century Arms began marketing a similar semi-auto only carbine manufactured by Wiselite Arms. These too have a 16-inch barrel. They are assembled using a mix of newly made US parts, and parts from demilitarized Sterling Mark 4 parts kits. This is often marketed as the Sterling Sporter.[38]

- Sterling Mark 7 "Para-pistol": Special machine pistol variant issued to commando and plainclothes intelligence units. It had a barrel shortened to 4 in (100 mm), fixed vertical foregrip, and weighed 4.84 lb (2.20 kg). If used with a short 10- or 15-round magazine, it could be stowed in a special holster. It also could be used as a Close Quarters Battle weapon with the addition of an optional solid stock.

- Canadian Army

- C1 Submachine Gun: Adopted in 1958, replacing the STEN gun in general service.[35] It was different from the British L2 in that it made extensive use of stamped metal parts rather the more expensive castings used by British production SMGs.[35] It also had a removable trigger guard for use with gloves in arctic operations as a standard option, and used a different 30-round magazine with a stamped metal follower. A 10-round magazine was also available for crews of armoured vehicles.

- Indian Army

- SAF Carbine 1A: Indian made Sterling L2A1.

- SAF Carbine 2A1: Sterling Mark V silenced carbine.

7.62 NATO variant

A prototype rifle in the 7.62×51mm NATO calibre was manufactured, using some components from the SMG. The rifle used lever-delayed blowback to handle the more powerful rounds and was fed from 30-round Bren magazines.[39] To prevent ammunition cookoff, the weapon fired from an open bolt. Only one model of the rifle was produced, possibly to test the concepts of a proposed new product. It was not put into production.

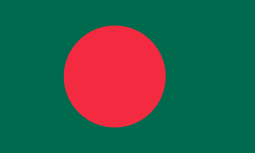

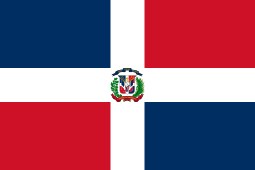

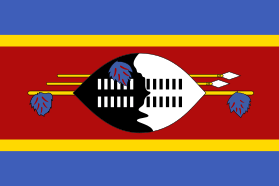

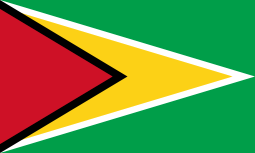

Users

_while_conducting_a_visit%2C_board%2C_search%2C_and_seizure_drill.jpg)

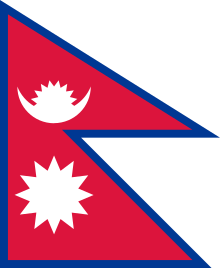

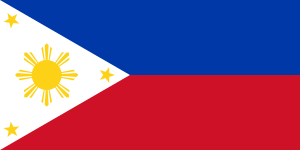

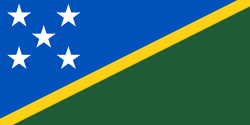

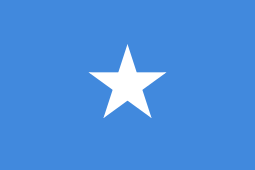

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

- CETME C2 submachine gun

- F1 submachine gun

- Lanchester submachine gun

- E-11 blaster rifle, a prop from the Star Wars film universe based on the Sterling frame.

References

Citations

- Moss 2018, pp. 41-44.

- Moss 2018, pp. 38-41.

- "Contre les Mau Mau". Encyclopédie des armes : Les forces armées du monde (in French). XII. Atlas. 1986. pp. 2764–2766.

- Moss 2018, p. 46.

- Perez, Jean-Claude (March 1992). "Les armes de l'O.A.S." Gazette des Armes (in French). No. 220. pp. 28–30. Archived from the original on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- Moss 2018, pp. 49-51.

- Moss 2018, p. 47.

- "Arms for freedom". 29 December 2017. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- Moss 2018, p. 73.

- Jowett, Philip (2016). Modern African Wars (5): The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967-70. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Press. p. 19&43. ISBN 978-1472816092.

- Moss 2018, p. 65.

- Moss 2018, pp. 51-52.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (1993). Armies of the Gulf War. Elite 45. Osprey Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 9781855322776.

- Alpeyrie, Jonathan. "English: Three Maoist rebels are waiting on top of a hill in the Rolpa district to get orders to relocate to another location".

- Small Arms Survey (2012). "Surveying the Battlefield: Illicit Arms In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets. Cambridge University Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-521-19714-4. Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- Jenzen-Jones, N.R.; McCollum, Ian (April 2017). Small Arms Survey (ed.). Web Trafficking: Analysing the Online Trade of Small Arms and Light Weapons in Libya (PDF). Working Paper No. 26. p. 95. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-08-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Patchett 9 mm Mk I experimental sub machine gun, 1944 (c) | Online Collection | National Army Museum, London". Nam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Patchett". firearms.96.lt. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "FIREARMS CURIOSA, Patchett machine-carbine In 1942, George William". Augfc.tumblr.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-13. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- According to Matthew Moss (Moss 2018, p. 38), "Despite much research, however, there is currently no documentary evidence to suggest that trials Patchetts found their way to the legendary battle that consumed Arnhem"

- "Patchett guns". Haulerwijk.com. 2015-04-19. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Patchett Machine Carbine Mk1 (FIR 6232)". Iwm.org.uk. 1999-02-22. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Capt. P.C Beckett and Lt.Col. RWP Dawson, DSO., Dec.1945". Gallery.commandoveterans.org. 2013-08-28. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Patchett Machine Carbine Mk1 (FIR 6365)". Iwm.org.uk. 1999-02-22. Archived from the original on 2018-04-03. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- "Patchett 9mm Machine Carbine, Experimental (FIR 6160)". Iwm.org.uk. 2005-06-01. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- Rinzler, JW (2013-10-22). The Making of Star Wars (Enhanced Edition). New York: Random House LLC. pp. 636–637. ISBN 978-0-345-54286-1.

- Fowler, Will (2009). Royal Marine Commando 1950–82: From Korea to the Falklands. Osprey. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-1-84603-372-8.

- Cutshaw, Charles Q. (28 February 2011). Tactical Small Arms of the 21st Century: A Complete Guide to Small Arms From Around the World. Iola, wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-1-4402-2709-7.

- Lyles, Kevin (2004). Vietnam ANZACs: Australian & New Zealand troops in Vietnam 1962–72. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-702-4. p. 62 Archived 2014-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Moss 2018, p. 57.

- Sterling 9mm MK4 SMG Sub Machine Gun on YouTube

- Moss 2018, p. 5.

- https://modernfirearms.net/en/submachine-guns/chile-submachine-guns/famae-paf-2/

- http://mpmuseum.org/securweapon.html

- "C1 Submachine Gun". Archived from the original on 2009-05-25. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190801055310/http://saf.gov.in/product.html

- https://pib.gov.in/newsite/erelcontent.aspx?relid=84268

- "Loading". www.wlawarehouse.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "British .308 Sterling prototype – Forgotten Weapons". Forgottenweapons.com. 2013-10-24. Archived from the original on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35 edition (January 27, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- Nick van der Bijl (1992). Argentine Forces in the Falklands. Osprey Publishing. p. 25.

- Fitzsimmons, Scott (November 2012). "Callan's Mercenaries Are Defeated in Northern Angola". Mercenaries in Asymmetric Conflicts. Cambridge University Press. p. 155. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139208727.005. ISBN 9781107026919.

- Horner, David (2002). SAS Phantoms of War: A History of the Australian Special Air Service. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508647-9.

- Moss 2018, p. 64.

- Miller, David (2001). The Illustrated Directory of 20th Century Guns. Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 1-84065-245-4.

- "SUB MACHINE GUN CARBINE 9 mm 1A1". Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- "Caracal & SIG Sauer Win Indian Army Deal". Mönch Publishing Group. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- https://silahreport.com/2018/03/13/guest-post-iraqi-contract-sterling-mk-4-in-syria/

- "How Much Does a Gun Cost in Kurdistan?: Militants' advance means booming business for Kurdish weapon dealers". 2014-08-21. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ncoicinnet. "Web Site of the Jamaica Defence Force". Jdfmil.org. Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- Leroy Thompson (20 September 2012). The Sten Gun. Osprey Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-78096-125-5. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "World Infantry Weapons: Libya". Archived from the original on 5 October 2016.

- Ezell, Eward. Small Arms Today (Stackpole, 1988)

- "M3 Grease Guns Re-issued". 2005-02-22. Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- Peter G. Locke (1995). Fighting vehicles and weapons of Rhodesia, 1965-80. p. 104.

- Kerrin Cocks (2015). Rhodesian Fire Force 1966-80. p. 12. ISBN 978-1910294055.

- Capie, David (2004). Under the Gun: The Small Arms Challenge in the Pacific. Wellington: Victoria University Press. pp. 65–67. ISBN 978-0864734532.

- Diez, Octavio (2000). Armament and Technology. Lema Publications, S.L. ISBN 84-8463-013-7.

Bibliography

- Hogg, Ian V., and John H. Batchelor. The Complete Machine-Gun, 1885 to the Present. London: Phoebus, 1979. ISBN 0-7026-0052-0.

- Paulson, A.C. 1990. The Sterling Mk4 submachine gun. Machine Gun News. 4(3):14-17.

- Edmiston, James. The Sterling Years. Leo Cooper Books, London. 1992. ISBN 085052-343-5.

- Gordon Rottman: Armies of the Gulf War. Osprey Military, London UK. 1993. p 31. ISBN 1-85532-277-3.

- Laidler, P., and D. Howroyd. The Guns of Dagenham. Collector Grade Publications, Cobourg, Ontario.1995. ISBN 0-88935-204-6.

- Paulson, A.C. 1996. Required reading: The Sterling Years. Fighting Firearms. 4(1):24,72-75.

- Paulson, A.C. 1996. Mystique, mystery and misinformation: suppressed Sterling Patchett Mark 5. Fighting Firearms. 4(1):50-56,75-76.

- Paulson, A.C. 1996. Best of the breed; evolution of the Mark 4 smg. Fighting Firearms. 4(3):22-27,77-78.

- Paulson, A.C. 1997. Required reading: The Guns of Dagenham: Lanchester, Patchett, Sterling. Fighting Firearms. 5(1):47,81-82.

- Paulson, A.C., N.R. Parker, and P.G. Kokalis. Silencer History and Performance. Volume 2. CQB, Assault Rifle, and Sniper Technology. Paladin Press, Boulder, Colorado. 2002. ISBN 1-58160-323-1.

- Paulson, A.C. 2005. Saddam’s SMG. Up close and personal with the 9mm Sterling Mark 4! Special Weapons for Military and Police. 33:76-81.

- Moss, Matthew (29 Nov 2018). The Sterling Submachine Gun. Weapon 65. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472828088.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Sterling submachine gun | |

- Sterling SMG – Official User's Manual

- Photos of prototype Patchett SMGs dating from early 1944

- Photos of a Patchett 9mm Mk I experimental sub machine gun from 1944 (c)

- Sterling 7.62×51mm NATO variant

- Chrome Plated L2A3 and 7.62 NATO variant

- Modern Firearms including several pictures of the various models.

- Sterling L2 at SecurityArms

- Sub Machine Gun Carbine 9 mm 1A1, Sterling L2A3 machine carbine manufactured under license by Indian State Ordnance Factory Board.

- Sub Machine Gun Carbine 9 mm 2A1 (Silent Version), Sterling L34A1 silenced machine carbine manufactured under license by Indian State Ordnance Factory Board.

- Image of a MK7 (Para Pistol)

- Image of a FAMAE PAF (Chilean Manufactured)

- Video of L2A3 being fired

- Video of Sterling Mk5 Silencer (L34A1) (in Japanese)

- Markings and Spares - sterlingl2a3.com