Panzerfaust

The Panzerfaust (German: [ˈpantsɐˌfaʊst], lit. "armor fist" or "tank fist", plural: Panzerfäuste) was an inexpensive, single shot, recoilless German anti-tank weapon of World War II. It consisted of a small, disposable pre-loaded launch tube firing a high-explosive anti-tank warhead, and was intended to be operated by a single soldier. The Panzerfaust's direct ancestor was the similar, smaller-warhead Faustpatrone ordnance device. The Panzerfaust was in use from 1943 until the end of the war.[1][2] The weapon's concepts played an important part in the development of the later Russian RPG weapon systems such as the RPG-2.[3] Most notably, the RPG-7 added a sustainer rocket motor to the projectile.

| Panzerfaust | |

|---|---|

A Wehrmacht Gefreiter aims a Panzerfaust using the integrated leaf sight | |

| Type | Man-portable anti-tank recoilless gun |

| Place of origin | Nazi Germany |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1943–1945 (Germany) |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | World War II |

| Production history | |

| Unit cost | 15-25 Reichmark |

| Produced | 1942–1945 |

| No. built | 6.7 million (all variants) |

| Variants | Panzerfaust 30, 60, 100, 150, 250 |

| Specifications (Panzerfaust 60) | |

| Mass | 6.25 kg (13.8 lb) |

| Length | ~ 1 m (3 ft 3 in) |

| Effective firing range | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Sights | leaf |

| Filling | Shaped charge |

Detonation mechanism | Impact |

Background: Faustpatrone

A forerunner of the Panzerfaust was the Faustpatrone (literally "fist cartridge").

The Faustpatrone was much smaller in physical appearance than the better known Panzerfaust. Development of the Faustpatrone started in the summer of 1942 at the German company Hugo Schneider AG (HASAG) with the development of a smaller prototype called Gretchen ("little Greta") by a team headed by Dr. Heinrich Langweiler in Leipzig. The basic concept was that of a recoilless gun; in the Faustpatrone and the Panzerfaust a propellent charge pushed the warhead out the front of the tube while the blast also exited the rear of the tube balancing forces and therefore there was no recoil force for the operator.

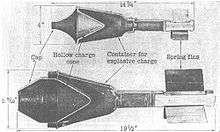

The following weapon, the Faustpatrone klein, 30 m ("small fist-cartridge") weighed 3.2 kg (7.1 lb) and a total length of 98.5 cm (38¾ in); its projectile had a length of 36 cm (14¼ in). The 10 cm (3.9 in) diameter of warhead was a shaped charge of 400 g (14 oz) of a 50:50 mix of TNT and tri-hexogen. The propellant was of 54 g (1.9 oz, 830 grains) of black powder, the metal launch tube had a length of 80 cm (31½ in) and a diameter of 3.3 cm (1.3 in) (early models reportedly 2.8 cm (1.1 in)). Fitted to the warhead was a wooden shaft with folded stabilizing fins (made of 0.25 mm (0.01 in) thick spring metal). These bent blades straightened into position by themselves as soon as they left the launch tube. The warhead was accelerated to a speed of 28 m/s (92 ft/s), had a range of about 30 m (100 ft) and an armor penetration of up to 140 mm (5½ in) of plain steel.

Soon a crude aiming device similar to the one used by the Panzerfaust was added to the design; it was fixed at a range of 30 m (100 ft). Several designations of this weapon were in use, amongst which Faustpatrone 1 or Panzerfaust 30 klein; however, it was common to refer to this weapon simply as the Faustpatrone. Of the earlier model, 20,000 were ordered and the first 500 Faustpatronen were delivered by the manufacturer, HASAG, Werk Schlieben, in August 1943.

Development

Development began in 1942 on a larger version of the Faustpatrone. The resulting weapon was the Panzerfaust 30, with a total weight of 5.1 kilograms (11.2 lb) and total length of 104.5 centimetres (3.4 ft). The launch tube was made of low-grade steel 44 millimetres (1.7 in) in diameter, containing a 95-gram (3.4 oz) charge of black powder propellant. Along the side of the tube were a simple folding rear sight and a trigger. The edge of the warhead was used as the front sight. The oversize warhead (140 mm (5.5 in) in diameter) was fitted into the front of the tube by an attached wooden tail stem with metal stabilizing fins.

The warhead weighed 2.9 kilograms (6.4 lb) and contained 0.8 kilograms (1.8 lb) of a 50:50 mixture of TNT and hexogen explosives, and had armour penetration of 200 millimetres (7.9 in).[7] The Panzerfaust often had warnings written in large red letters on the upper rear end of the tube, the words usually being "Achtung. Feuerstrahl." ("Beware. Fire jet."). This was to warn soldiers to avoid the backblast.

After firing, the tube was discarded, making the Panzerfaust the first disposable anti-tank weapon. The weapon, when correctly fired from the crook of the arm, could with its shaped charge warhead penetrate the armour of any armoured fighting vehicle of the period.[8]

Comparison of models

| Designation | Weight | Propellant weight |

Warhead diameter |

Projectile velocity |

Effective range |

Penetration performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faustpatrone 30 Panzerfaust (Klein) 30m |

2.7–3.2 kg (5 lb 15 oz–7 lb 1 oz) | 70 g (2.5 oz) | 100 mm (3.9 in) | 28 m/s (63 mph) | 30 m (98 ft) | 140 mm (5.5 in) |

| Panzerfaust 30 Panzerfaust (Gross) 30m |

5.22 kg (11.5 lb) | 95–100 g (3.4–3.5 oz) | 149 mm | 30 m/s | 30 m | 200 mm |

| Panzerfaust 60 | 6.8 kg | 120–134 g | 149 mm | 45 m/s | 60 m | 200 mm |

| Panzerfaust 100 | 6.8 kg (15 lb) | 190–200 g (6.7–7.1 oz) | 149 mm | 60 m/s | 100 m (330 ft) | 200 mm (7.9 in) |

| Panzerfaust 150 | 7 kg (15 lb) | 190–200 g (6.7–7.1 oz) | 106 mm (4.2 in) | 85 m/s (190 mph) | 150 m (490 ft) | 280–320 mm (11–13 in) |

Combat use

To use the Panzerfaust, the soldier took off the safety, tucked the tube under their arm and aimed by aligning the target, the sight, and the top of the warhead. Unlike the Americans' original M1 60 mm Bazooka and the Germans' own heavier 88 mm Panzerschreck tube-type rocket launchers based on the American ordnance piece, the Panzerfaust did not have a trigger. It had a pedal-like lever near the projectile that ignited the propellant when squeezed. Because of the short range, not only enemy tanks and infantry, but also pieces of the exploding vehicle were dangerous to the soldier. So the usage of Panzerfaust required great personal courage.[9][10] The backblast from firing went back around 2 m behind the operator.

When used against tanks, the Panzerfaust had an impressive beyond-armour effect. Compared to the Bazooka and the Panzerschreck, it made a larger hole and produced massive spalling that killed or injured (burns, shrapnels) the crew and destroyed equipment. One informal test found that the Panzerfaust made an entry hole two and three-fourths inches in diameter (~7 cm), whereas the Panzerschreck made an entry hole at least one inch in diameter (~2.5 cm), and the Bazooka made an entry hole that was only a half-inch in diameter (~1.3 cm).[11] Much of this can be attributed not only to the size of the Panzerfaust's warhead but also its horn-like shape as opposed to the traditional cone-shaped warheads of the Bazooka and Panzerschreck. This design was later copied in the modern day AT-4 to produce the same effect against modern main battle tanks.

Germany

In the Battle of Normandy, only 6% of British tank losses were from Panzerfaust fire despite the close-range combat in the bocage landscape. However, the threat from the Panzerfaust forced tank forces to wait for infantry support before advancing. The portion of British tanks taken out of action by Panzerfäuste later rose to 34%, a rise probably explained by the lack of German anti-tank guns late in the war and the increased numbers of Panzerfäuste that were available.[12]

In urban combat later in the war in eastern Germany, about 70% of tanks destroyed were hit by Panzerfäuste or Panzerschrecks. The Soviet forces responded by installing spaced armour on their tanks from early 1945 onwards. Western allied tanks were modified in the field in order to provide some protection against Panzerfaust, including to logs, sandbags, track links, and wire mesh like German skirts. In practice about 1 metre of air gap was required to substantially reduce the penetrating capability of the warhead, thus skirts and sandbags were virtually entirely ineffective against Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust, but the additions did overburden the vehicle's engine, transmission, and suspension systems.[13]

Later on, each Soviet heavy tank (IS) and assault gun (ISU-152) company had assigned a platoon of infantry in urban battles to protect them from infantry-wielded, anti-tank weapons and were often supported by flamethrowers. This order remained intact even during '50s and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.[13][14][15]

During the last stages of the war, due to the lack of available weapons, many poorly-trained conscripts (mainly elderly men) and teenage Hitler Youth members were often given a single Panzerfaust plus any type of obsolete pistols. This caused several German generals to comment sarcastically that the empty launch-tubes could then be used as clubs in hand-to-hand combat.

Other countries

Many Panzerfäuste were sold to Finland, which urgently needed them, as the Finnish forces did not have enough anti-tank weapons that could penetrate heavily armored Soviet tanks like the T-34 and IS-2. The Finnish experience with the weapon and its adaptability to Finnish needs was mixed, and only 4,000 of 25,000 Panzerfäuste delivered were expended in combat.[16] The manual that came with the weapon upon delivery to the Finns included depictions of where to aim the weapon on the Soviet T-34 and US Sherman tank (which also saw service with Soviet troops from US Lend-Lease-supplied stocks).[17]

The Italian Social Republic (RSI) and the Government of National Unity (Hungary) also used the Panzerfaust. Several RSI army units became skilled in anti-tank warfare and the Hungarians themselves used the Panzerfaust extensively, especially during the Siege of Budapest. During this brutal siege, an arms factory, the Hungarian Manfred Weiss Steel and Metal Works, located on Csepel Island (within the city) kept up production of various light armaments and ammunition, Panzerfäuste included, all the way until the very last moment, when attacking Soviet troops seized the factory by the first days of 1945.

The US 82nd Airborne Division captured some Panzerfäuste in the Allied invasion of Sicily, and later during the fighting in Normandy. Finding them more effective than their own Bazookas, they held onto them and used them during the later stages of the French campaign, even dropping with them into the Netherlands during Operation Market Garden. They captured an ammunition dump of Panzerfäuste near Nijmegen, and used them through the Ardennes Offensive toward the end of the war.[18]

The Soviet army only incidentally used captured Panzerfäuste in 1944, but from beginning of 1945 many became available and were used during Soviet 1945 offensives, mostly in street fighting against buildings and covers.[19] In February 1945 such use of captured Panzerfäuste was recommended in a directive by Marshall Georgiy Zhukov.[19] Similarly they were used by the Polish People's Army.[19] After the war some 4,000 Panzerfäuste were adapted by the Polish Army in 1949, designated as PG-49.[19]

Plans and technical materials on the Panzerfaust were supplied to the Empire of Japan to assist with their development of an effective anti-tank weapon. However, the Japanese went with a different design, the Type 4, loosely based upon the American Bazooka. Examples of the American weapon were captured on Leyte.[20]

Variants

- Panzerfaust 30 klein ("small") or Faustpatrone

- This was the original version, first delivered in August 1943 with a total weight of 3.2 kilograms (7.1 lb) and overall length of 98.5 cm (38.8 in). The "30" was indicative of the nominal maximum range of 30 m (33 yd). It had a 3.3 cm (1.3 in) diameter tube containing 54 grams (1.9 oz) of black powder propellant launching a 10 cm (3.9 in) warhead carrying 400 g (14 oz) of explosive. The projectile traveled at just 30 m (98 ft) per second and could penetrate 140 mm (5.5 in) of armour.

- Panzerfaust 30

- An improved version also appearing in August 1943. This version had a larger warhead for improved armor penetration, 200 mm (7.9 in) of steel and 5.5 inches (140 mm) of armored steel, but the same range of 30 meters. It has an explosive charge of 3.3 pounds (1.5 kg) of explosive material. Its barrel has a caliber of 1.7 inches (43 mm) and a length of 40.6 inches (103 cm). It has a weight of 11.2 pounds (5.1 kg) and a muzzle velocity of 148 feet per second (45 m/s).[21]

- Panzerfaust 60

- This was the most common version, and was completed in early 1944. However, it did not reach full production until September 1944, when 400,000 were to be produced each month.[22] It had a much more practical range of 60 m (66 yd), although with a muzzle velocity of only 45 m (148 ft) per second it would take 1.3 seconds for the warhead to reach a tank at that range. To achieve the higher velocity, the tube diameter was increased to 5 cm (2.0 in) and 134 g (4.7 oz) of propellant used while being a total length of 104 cm (41 in). It also had an improved flip-up rear sight and trigger mechanism. The weapon now weighed 6.1 kg (13 lb). It could defeat 200 mm (7.9 in) of armour.

- Panzerfaust 100

- This was the final version produced in quantity, and was completed in September 1944. However, it did not reach full production until November 1944.[22] It had a nominal maximum range of 100 m (330 ft). 190 g (6.7 oz) of propellant launched the warhead at 60 m (200 ft) per second from a 6 cm (2.4 in) diameter tube. The sight had holes for 30, 60, 80 and 150 m (260 and 490 ft), and had luminous paint in them to make counting up to the correct one easier in the dark. This version weighed 6 kg (13 lb) and could penetrate 220 mm (8.7 in) of armour.

- Panzerfaust 150

- This was a major redesign of the weapon, and was deployed in limited numbers near the end of the war. The firing tube was reinforced and reusable for up to ten shots. A new pointed warhead with increased armour penetration and two-stage propellant ignition gave a higher velocity of 85 m (279 ft) per second. Production started in March 1945, two months before the end of the war.

- Panzerfaust 250

- The last development of the Panzerfaust series was the Panzerfaust 250. It used a reloadable tube and now featured a pistol grip. With propellants in both the firing tube and on the projectile itself it was projected to reach a projectile speed of 150 m/s (490 feet/s). Serial production was scheduled to begin in September 1945. However, the development of this weapon was never completed and none were ever produced. The Soviet RPG-2 anti-tank rocket launcher partially was based on the design of the Panzerfaust 250.

Related development

- PAPI

- Argentine-made antitank weapon, similar to the Panzerfaust. The acronym stands for proyectil antitanque para infanteria (Spanish for "infantry anti-tank projectile").[23]

- Pansarskott m/45 and pansarskott m/46

- Swedish-made copies of the Panzerfaust.[24]

- Pc-100 (PC-100, pancerzownica 100m)

- Polish-made copy of the Panzerfaust 100, manufactured in 1951–1952. Despite large-scale orders, a production encountered technological difficulties and only 5000 combat and 940 training Pc-100 were made in 1952, before the Polish Army switched to more modern Soviet RPG-2.[25] It is erroneously known as PT-100 in foreign publications.[25]

Users

- Panzerfaust

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Derivatives

See also

References

Notes

- Stallings, Patrick A. "Tank Company Security Operations" (PDF). Major.

- Guzmán, Julio S. (April 1942). Las Armas Modernas de Infantería (in Spanish).

- Very similar o the Panzerfaust 250

- "Panzerfaust 100, courtesy of V. Potapov".

- "Reocities, Panzerfaust WW II German Infantry Anti-Tank Weapons Page 2: Faustpatrone & Panzerfaust, M.Hofbauer".

- "Panzerfaust WW II German Infantry Anti-Tank Weapons Page 2: Faustpatrone & Panzerfaust, M.Hofbauer". Archived from the original on February 9, 2005.

- Handbook on German Military Forces (PDF). Washington D.C.: United States War Department. 1945. p. VII-II.

- Bishop, Chris (January 1998). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. New York: Orbis Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7607-1022-7.

- "A Panzerfaust | A II. Világháború Hadtörténeti Portálja". www.roncskutatas.com. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- David Ackerman, edited by Jonathan Bocek. "The Panzerfaust". der Erste Zug. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- White, Isaac D. United States vs. German Equipment: As Prepared for the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force (1997). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p 70. ISBN 978-1468068153.

- Place, Timothy Harrison (October 2000). "Chapter 9: Armour in North-West Europe". Military training in the British Army, 1940–1944: From Dunkirk to D-Day. Cass Series—Military History and Policy. 6. London: Frank Cass. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7146-5037-1. LCCN 00031480.

- Chamberlain, Peter (1974). Anti-tank weapons. Arco. ISBN 0668036079.

- "Molnár György: A szovjet hadsereg 1956-ban". beszelo.c3.hu. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- Laurenszky, Ernő (1995). A forradalom fegyverei - 1956 (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Honvédség OKAK.

- Jowett, Philip S.; Snodgrass, Brent (Illustrator); Ruggeri, Raffaele (Illustrator) (July 2006). Martin Windrow (ed.). Finland at War, 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84176-969-1. LCCN 2006286373.

- "Jack E. Hammond, hosting of 1943 Panzerfaust manual".

- More Than Courage: Sicily, Naples-Foggia, Anzio, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace ... By Phil Nordyke P.299

- Perzyk, Bogusław: Niemieckie granatniki przeciwpancerne Panzerfaust w Wojsku Polskim 1944-1955 cz.I in: Poligon 2/2011, pp.56-62 (in Polish)

- Gordon L. Rottman (2014). Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck. Osprey Publishing. pp. 72–73. ISBN 1782007881.

- Weapons of World War II by Alexander Ludeke

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2014). Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781782007883.

- "Argentine Panzerfaust" topic, International Ammunition Association forum (retrieved 2014-01-24)

- Pansarskott Swedish Wikipedia article, accessed 2012-11-15

- Perzyk, Bogusław: Panzerfaust w Wojsku Polskim 1944-1955 cz.II. Projekt PC-100 in: Poligon 4/2011, pp. 68–80 (in Polish)

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2014). "The Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck in other hands". Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck. Osprey Publishing. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9781782007883.

- Tibor, Rada (2001). "Német gyalogsági fegyverek magyar kézben" [German infantry weapons in Hungarian hands]. A Magyar Királyi Honvéd Ludovika Akadémia és a Testvérintézetek Összefoglalt Története (1830-1945) (in Hungarian). II. Budapest: Gálos Nyomdász Kft. p. 1114. ISBN 963-85764-3-X.

- Bartošek, Karel (1965). The Prague Uprising. Artia. p. 53.

- Julio S. Guzmán, Las Armas Modernas de Infantería, Abril de 1953

- "Support Weapons". Militariarg.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Chuikov, Vasili Ivanovich; Kisch, Ruth (translator) (1969). The End of the Third Reich. Panther Books. ISBN 978-0-586-02775-2. LCCN 74534462.