Manjushri

Mañjuśrī is a bodhisattva associated with prajñā (insight) in Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Tibetan Buddhism, he is also a yidam. His name means "Gentle Glory" in Sanskrit.[1] Mañjuśrī is also known by the fuller name of Mañjuśrīkumārabhūta,[2] literally "Mañjuśrī, Still a Youth" or, less literally, "Prince Mañjuśrī". Another deity by the name of Mañjuśrī is Mañjughoṣa.

| Mañjuśrī | |

|---|---|

%2C_India%2C_Pala_dynesty%2C_9th_century%2C_stone%2C_Honolulu_Academy_of_Arts.jpg) Mañjuśrī Pala Dynasty, India, 9th century CE. | |

| Sanskrit | मञ्जुश्री

Mañjuśrī |

| Chinese | 文殊菩薩 (Pinyin: Wénshū Púsà) 文殊师利菩薩 (Pinyin: Wénshūshīlì Púsà) 曼殊室利菩薩 (Pinyin: Mànshūshìlì Púsà) 妙吉祥菩薩 (Pinyin: Miàojíxiáng Púsà) |

| Japanese | (romaji: Monju Bosatsu) (romaji: Monjushiri Bosatsu) (romaji: Monju Bosatsu) (romaji: Myōkisshō Bosatsu) |

| Khmer | មញ្ចុស្រី (manh-cho-srei) |

| Korean | 문수보살 (RR: Munsu Bosal) 만수보살 (RR: Mansu Bosal) 묘길상보살 (RR: Myokilsang Bosal) |

| Mongolian | ᠵᠦᠭᠡᠯᠡᠨ ᠡᠭᠰᠢᠭᠲᠦ Зөөлөн эгшигт |

| Thai | พระมัญชุศรีโพธิสัตว์ |

| Tibetan | འཇམ་དཔལ་དབྱངས་ Wylie: 'jam dpal THL: jampal འཇམ་དཔལ་ Wylie: 'jam dpal dbyang THL: Jampalyang |

| Vietnamese | Văn Thù Sư Lợi Bồ Tát Văn-thù Diệu Đức Diệu Cát Tường Diệu Âm |

| Information | |

| Venerated by | Mahayana, Vajrayana |

In Mahāyāna Buddhism

Scholars have identified Mañjuśrī as the oldest and most significant bodhisattva in Mahāyāna literature.[3] Mañjuśrī is first referred to in early Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras and through this association, very early in the tradition he came to symbolize the embodiment of prajñā (transcendent wisdom).[2] The Lotus Sutra assigns him a pure land called Vimala, which according to the Avatamsaka Sutra is located in the East. His pure land is predicted to be one of the two best pure lands in all of existence in all the past, present, and future. When he attains buddhahood his name will be Universal Sight. In the Lotus Sūtra, Mañjuśrī also leads the Nagaraja's daughter to enlightenment. He also figures in the Vimalakīrti Sūtra in a debate with Vimalakīrti where he is presented as an Arhat who represents the wisdom of the Hīnayāna.

An example of a wisdom teaching of Mañjuśrī can be found in the Saptaśatikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (Taishō Tripiṭaka 232).[4] This sūtra contains a dialogue between Mañjuśrī and the Buddha on the One Samādhi (Skt. Ekavyūha Samādhi). Sheng-yen renders the following teaching of Mañjuśrī, for entering samādhi naturally through transcendent wisdom:

Contemplate the five skandhas as originally empty and quiescent, non-arising, non-perishing, equal, without differentiation. Constantly thus practicing, day or night, whether sitting, walking, standing or lying down, finally one reaches an inconceivable state without any obstruction or form. This is the Samadhi of One Act (yixing sanmei, 一行三昧).[5]

Vajrayāna Buddhism

Within Vajrayāna Buddhism, Mañjuśrī is a meditational deity and considered a fully enlightened Buddha. In Shingon Buddhism, he is one of the Thirteen Buddhas to whom disciples devote themselves. He figures extensively in many esoteric texts such as the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa[2] and the Mañjuśrīnāmasamgīti. His consort in some traditions is Saraswati.

The Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa, which later came to classified under Kriyātantra, states that mantras taught in the Śaiva, Garuḍa, and Vaiṣṇava tantras will be effective if applied by Buddhists since they were all taught originally by Mañjuśrī.[6]

Iconography

Mañjuśrī is depicted as a male bodhisattva wielding a flaming sword in his right hand, representing the realization of transcendent wisdom which cuts down ignorance and duality. The scripture supported by the padma (lotus) held in his left hand is a Prajñāpāramitā sūtra, representing his attainment of ultimate realization from the blossoming of wisdom. Mañjuśrī is often depicted as riding on a blue lion or sitting on the skin of a lion. This represents the use of wisdom to tame the mind, which is compared to riding or subduing a ferocious lion.

In Chinese and Japanese Buddhist art, Mañjuśrī's sword is sometimes replaced with a ruyi scepter, especially in representations of his Vimalakirti Sutra discussion with the layman Vimalakirti.[7] According to Berthold Laufer, the first Chinese representation of a ruyi was in an 8th-century Mañjuśrī painting by Wu Daozi, showing it held in his right hand taking the place of the usual sword. In subsequent Chinese and Japanese paintings of Buddhas, a ruyi was occasionally represented as a Padma with a long stem curved like a ruyi.[8]

He is one of the Four Great Bodhisattvas of Chinese Buddhism, the other three being Kṣitigarbha, Avalokiteśvara, and Samantabhadra. In China, he is often paired with Samantabhadra.

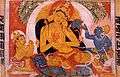

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mañjuśrī is sometimes depicted in a trinity with Avalokiteśvara and Vajrapāṇi.

Mantras

A mantra commonly associated with Mañjuśrī is the following:[9]

- oṃ arapacana dhīḥ

The Arapacana is a syllabary consisting of forty-two letters, and is named after the first five letters: a, ra, pa, ca, na.[10] This syllabary was most widely used for the Gāndhārī language with the Kharoṣṭhī script but also appears in some Sanskrit texts. The syllabary features in Mahāyāna texts such as the longer Prajñāpāramitā texts, the Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra, the Lalitavistara Sūtra, the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, and the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya.[10] In some of these texts, the Arapacana syllabary serves as a mnemonic for important Mahāyāna concepts.[10] Due to its association with him, Arapacana may even serve as an alternate name for Mañjuśrī.[9]

The Sutra on Perfect Wisdom (Conze 1975) defines the significance of each syllable thus:

- A is a door to the insight that all dharmas are unproduced from the very beginning (ādya-anutpannatvād).

- RA is a door to the insight that all dharmas are without dirt (rajas).

- PA is a door to the insight that all dharmas have been expounded in the ultimate sense (paramārtha).

- CA is a door to the insight that the decrease (cyavana) or rebirth of any dharma cannot be apprehended, because all dharmas do not decrease, nor are they reborn.

- NA is a door to the insight that the names (i.e. nāma) of all dharmas have vanished; the essential nature behind names cannot be gained or lost.

Tibetan pronunciation is slightly different and so the Tibetan characters read: oṃ a ra pa tsa na dhīḥ (Tibetan: ༀ་ཨ་ར་པ་ཙ་ན་དྷཱི༔, Wylie: om a ra pa tsa na d+hIH ).[11] In Tibetan tradition, this mantra is believed to enhance wisdom and improve one's skills in debating, memory, writing, and other literary abilities. "Dhīḥ" is the seed syllable of the mantra and is chanted with greater emphasis and also repeated a number of times as a decrescendo.

In Buddhist cultures

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Transmission |

|

Teachings

|

|

Mahāyāna sūtras |

.jpg)

In China

Mañjuśrī is known in China as Wenshu (Chinese: 文殊; pinyin: Wénshū). Mount Wutai in Shanxi, one of the four Sacred Mountains of China, is considered by Chinese Buddhists to be his bodhimaṇḍa. He was said to bestow spectacular visionary experiences to those on selected mountain peaks and caves there. In Mount Wutai's Foguang Temple, the Manjusri Hall to the right of its main hall was recognized to have been built in 1137 during the Jin dynasty. The hall was thoroughly studied, mapped and first photographed by early twentieth-century Chinese architects Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin.[12] These made it a popular place of pilgrimage, but patriarchs including Linji Yixuan and Yunmen Wenyan declared the mountain off limits.[13]

Mount Wutai was also associated with the East Mountain Teaching.[14] Mañjuśrī has been associated with Mount Wutai since ancient times. Paul Williams writes:[15]

Apparently the association of Mañjuśrī with Wutai (Wu-t'ai) Shan in north China was known in classical times in India itself, identified by Chinese scholars with the mountain in the 'north-east' (when seen from India or Central Asia) referred to as the abode of Mañjuśrī in the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. There are said to have been pilgrimages from India and other Asian countries to Wutai Shan by the seventh century.

According to official histories from the Qing dynasty, Nurhaci, a military leader of the Jurchens of Northeast China and founder of what became the Qing dynasty, named his tribe after Mañjuśrī as the Manchus.[16] The true origin of the name Manchu is disputed.[17]

Monk Hanshan (寒山) is widely considered to be a metaphorical manifestation of Mañjuśrī. He is known for having co-written the following famous poem about reincarnation with monk Shide:

Drumming your grandpa in the shrine,

Cooking your aunts in the pot,

Marrying your grandma in the past,

Should I laugh or not?

In Tibet

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mañjuśrī manifests in a number of different Tantric forms. Yamāntaka (meaning 'terminator of Yama i.e. Death') is the wrathful manifestation of Mañjuśrī, popular within the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. Other variations upon his traditional form as Mañjuśrī include Namasangiti, Arapacana Manjushri, etc.

In Nepal

According to Swayambhu Purana, the Kathmandu Valley was once a lake. It is believed that Mañjuśrī came on a pilgrimage from his earthly abode-Wutaishan(five-peaked mountain) in China. He saw a lotus flower in the center of the lake, which emitted brilliant radiance. He cut a gorge at Chovar with his flaming sword to allow the lake to drain. The place where the lotus flower settled became the great Swayambhunath Stupa and the valley thus became habitable.

In Indonesia

In eighth century Java during the Medang Kingdom, Mañjuśrī was a prominent deity revered by the Sailendra dynasty, patrons of Mahayana Buddhism. The Kelurak inscription (782) and Manjusrigrha inscription (792) mentioned about the construction of a grand Prasada named Vajrāsana Mañjuśrīgṛha (Vajra House of Mañjuśrī) identified today as Sewu temple, located just 800 meters north of the Prambanan. Sewu is the second largest Buddhist temple in Central Java after Borobudur. The depiction of Mañjuśrī in Sailendra art is similar to those of the Pala Empire style of Nalanda, Bihar. Mañjuśrī was portrayed as a youthful handsome man with the palm of his hands tattooed with the image of a flower. His right hand is facing down with an open palm while his left-hand holds an utpala (blue lotus). He also uses the necklace made of tiger canine teeth.

Gallery

Mañjuśrī figure brandishing sword of wisdom in Nepal

Mañjuśrī figure brandishing sword of wisdom in Nepal

Silver figure of Mañjuśrī holding a long-stemmed lotus. Central Java, Indonesia

Silver figure of Mañjuśrī holding a long-stemmed lotus. Central Java, Indonesia- Blanc de Chine figure of Mañjuśrī holding a ruyi scepter. China, 17th century

Mañjuśrī on lion with cintamani. Quan Âm Pagoda, Ho Chi Minh City

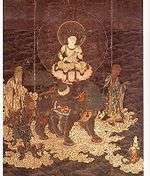

Mañjuśrī on lion with cintamani. Quan Âm Pagoda, Ho Chi Minh City Mañjuśrī crossing the sea. Japan

Mañjuśrī crossing the sea. Japan- Manjushri at Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum, Singapore

Bodhisattva Manjushri seated in lalitasana, from China, Jin Dynasty, 12th century CE. British Museum

Bodhisattva Manjushri seated in lalitasana, from China, Jin Dynasty, 12th century CE. British Museum

References

Citations

- Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2001). The Story of Buddhism: A Concise Guide to its History and Teachings. New York, USA: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-069976-0 (cloth) P.260.

- Keown, Damien (editor) with Hodge, Stephen; Jones, Charles; Tinti, Paola (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860560-9 p.172.

- A View of Manjushri: Wisdom and Its Crown Prince in Pala Period India. Harrington, Laura. Doctoral Thesis, Columbia University, 2002

- The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalog (T 232)

- Sheng-Yen, Master (聖嚴法師)(1988). Tso-Ch'an, p.364

- Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 129-131.

- Davidson, J. LeRoy, "The Origin and Early Use of the Ju-i", Artibus Asiae 1950,13.4, 240.

- Laufer, Berthold, Jade, a Study in Chinese Archaeology and Religion, Field Museum of Natural History, 1912, 339.

- Buswell, Robert. Lopez, Donald. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. 2013. p. 527

- Buswell, Robert. Lopez, Donald. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. 2013. p. 61

- - Visible Mantra's website

- Liang, Ssucheng. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture. Ed. Wilma Fairbank. Cambridge, Michigan: The MIT Press, 1984.

-

- See Robert M. Gimello, "Chang Shang-ying on Wu-t'ai Shan", in Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China:, ed. Susan Naquin and Chün-fang Yü (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), pp. 89–149; and Steven Heine, "Visions, Divisions, Revisions: The Encounter Between Iconoclasm and Supernaturalism in Kōan Cases about Mount Wu-t'ai", in The Kōan, pp. 137–167.

- Heine, Steven (2002). Opening a Mountain: Koans of the Zen Masters. USA: Oxford University Press. p. . ISBN 0-19-513586-5.

- Williams, Paul. Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. 2000. p. 227

- Agui (1988). 满洲源流考 (the Origin of Manchus). Liaoning Nationality Publishing House. ISBN 9787805270609.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yan, Chongnian (2008). 明亡清兴六十年 (彩图珍藏版). Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN 9787101059472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "诗僧寒山与拾得:文殊菩萨普贤菩萨化身" (in Chinese). Beijing: NetEase Buddhism Channel. 2014-12-10.

- 韩廷杰. "寒山诗赏析" (in Chinese). Zhejiang: 灵山海会期刊社.

- Doniger 1993, p. 243.

Sources

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1381-0

Further reading

Harrison, Paul M. (2000). Mañjuśrī and the Cult of the Celestial Bodhisattvas, Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 13, 157-193

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manjusri. |

.jpg)