Yulin Caves

The Yulin Caves (Chinese: 榆林窟; pinyin: Yulin kū) is a Buddhist cave temple site in Guazhou County, Gansu Province, China. The site is located some 100 km east of the oasis town of Dunhuang and the Mogao Caves. It takes its name from the eponymous elm trees lining the Yulin River, which flows through the site and separates the two cliffs from which the caves have been excavated. The forty-two caves house some 250 polychrome statues and 4,200 m2 of wall paintings, dating from the Tang Dynasty to the Yuan Dynasty (seventh to fourteenth centuries).[1][2] The site was among the first to be designated for protection in 1961 as a Major National Historical and Cultural Site.[3] In 2008 the Yulin Grottoes were submitted for future inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List as part of the Chinese Section of the Silk Road.[4]

Caves

Most of the caves take the form of an entrance corridor, antechamber, and main chamber. In three caves, a central pier was left intact during excavation then carved with niches on all four sides. A number of caves were reworked and repainted in later periods, since the site remained in use throughout the Tang, Five Dynasties, Song, Western Xia, and Yuan Dynasties. It fell into disuse during the Ming Dynasty. There were early efforts to restore the caves at the time of the Qing Dynasty and several new caves also date to this period. More recently, under the management of the Dunhuang Academy, the focus has been on preventive conservation through consolidation of the cliff face and controlling access.[1][5]

Wall paintings

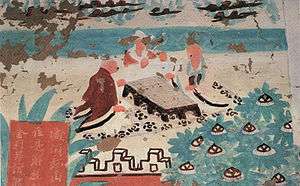

The paintings are Buddhist with some secular scenes, the former including buddhas, bodhisattvas, apsara, and jataka tales; and the latter, donor portraits, go players, representatives of China's ethnic minorities, marked out by their hair styles and dress, farming scenes such as milking a cow, wine-making, a smelting furnace, and a marriage ceremony; depictions of musicians and dancers help break down the distinction between the sacred and the profane.[1][2] The paintings are not frescoes but instead executed on an earthen render with mineral and organic pigments and gum or glue binders.[5]

List of caves

The forty-two caves are dated as follows, based largely on the style of the paintings and their accompanying inscriptions (in Chinese, Mongolian, Tibetan, Sanskrit, Tangut, and Old Uighur):[6][7]

| Cave | Construction | Restorations | Former Numbering | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cave 1 | Qing | |||

| Cave 2 | Western Xia | Yuan, Qing | C1 | .jpg) |

| Cave 3 | Western Xia | Yuan, Qing | C2 | .jpg) |

| Cave 4 | Yuan | Qing | C3 | .jpg) |

| Cave 5 | Tang | Qing | .jpg) | |

| Cave 6 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, Western Xia, Qing, Republic of China | C4 | |

| Cave 7 | Qing | |||

| Cave 8 | Qing | |||

| Cave 9 | Qing | |||

| Cave 10 | Western Xia | Yuan, Qing | C5 | .jpg) |

| Cave 11 | Qing | |||

| Cave 12 | Five Dynasties | Qing | C6 | .jpg) |

| Cave 13 | Five Dynasties | Song, Qing | C7 | |

| Cave 14 | Song Dynasty | Qing, Republic of China | C8 | |

| Cave 15 | Mid-Tang | Song, Western Xia, Yuan, Qing | C9 | .jpg) |

| Cave 16 | Five Dynasties | Early Republic of China | C10 | |

| Cave 17 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, (date unclear), Qing | C11 | |

| Cave 18 | Five Dynasties | Western Xia, Yuan | C11b | |

| Cave 19 | Five Dynasties | Qing | C12 | .jpg) |

| Cave 20 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, Qing | C13 | |

| Cave 21 | Tang | Song, (date unclear), Qing | C14 | |

| Cave 22 | Tang | Song, Western Xia, Qing | C15 | |

| Cave 23 | Tang | Song, Qing | C16 | |

| Cave 24 | Tang | C17b | ||

| Cave 25 | Mid-Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, Qing | C17 | .jpg) |

| Cave 26 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, (date unclear), Qing | C18 | |

| Cave 27 | Tang | C18b | ||

| Cave 28 | Early-Tang | Song, Western Xia, Qing | C19 | |

| Cave 29 | Western Xia | Yuan, Qing | C20 | .jpg) |

| Cave 30 | Late-Tang | Song | C20 | |

| Cave 31 | Five Dynasties | Qing | C21 | |

| Cave 32 | Five Dynasties | Song | C22 |  |

| Cave 33 | Five Dynasties | Qing | C23 | |

| Cave 34 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, Qing | C24 | |

| Cave 35 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, Qing | C25 | |

| Cave 36 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Song, Qing | C26 | |

| Cave 37 | Qing | |||

| Cave 38 | Tang | Five Dynasties, Qing | C27 | |

| Cave 39 | Tang | (date unclear), Yuan, Qing | C28 | .jpg) |

| Cave 40 | Five Dynasties | Qing | C29 | |

| Cave 41 | Five Dynasties | Yuan, Qing | ||

| Cave 42 | High-Tang |

See also

- Mogao Caves

- Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China

- National Heritage Sites in Gansu Province

- International Dunhuang Project

- World Heritage Sites in China

References

- Fan Jinshi, ed. (1999). 安西榆林窟 The Anxi Yulin Grottoes (in Chinese and English). Gansu National Publishing House. pp. 6–9. ISBN 7542106465.

- Dunhuang Academy, ed. (1997). 安西榆林窟 [Anxi Yulin Caves] (in Chinese). 文物出版社. ISBN 7501007748.

- "国务院关于公布第一批全国重点文物保护单位名单的通知 (1st Designations)" (in Chinese). State Administration of Cultural Heritage. 3 April 1961. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Chinese Section of the Silk Road". UNESCO. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Whitfield, Roderick (et al.) (2000). Cave Temples of Mogao: Art and History on the Silk Road. Getty Conservation Institute. pp. 5, 114 ff, 135. ISBN 0892365854.

- Dunhuang Academy, ed. (1997). 安西榆林窟 [Anxi Yulin Caves] (in Chinese). 文物出版社. pp. 254–263. ISBN 7501007748.

- Dai Matsui (2008). "Revising the Uigur Inscriptions of the Yulin Caves". Studies on the Inner Asian Languages. Osaka University. 23: 17–33. ISSN 1341-5670.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yulin Caves. |