Foguang Temple

Foguang Temple (Chinese: 佛光寺) is a Buddhist temple located five kilometres from Doucun, Wutai County, Shanxi Province of China. The major hall of the temple is the Great East Hall, built in 857 AD, during the Tang Dynasty (618–907). According to architectural records, it is the third earliest preserved timber structure in China. It was rediscovered by the 20th-century architectural historian Liang Sicheng (1901–1972) in 1937, while an older hall at Nanchan Temple was discovered by the same team a year later.[1] The temple also contains another significant hall dating from 1137 called the Manjusri Hall. In addition, the second oldest existing pagoda in China (after the Songyue Pagoda), dating from the 6th century, is located in the temple grounds.[2] Today the temple is part of a UNESCO World Heritage site and is undergoing restoration.

| Foguang Temple | |

|---|---|

The Great East Hall of the Foguang Temple | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Buddhist |

| Province | Shanxi |

| Location | |

| Location | Wutaishan |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | 857 CE Tang Dynasty |

| Foguang Temple | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Foguang Temple" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 佛光寺 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Temple of Buddha's Light" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

History

The temple was established in the fifth century during the Northern Wei dynasty. From the years of 785 to 820, the temple underwent an active building period when a three level, 32 m tall pavilion was built.[3] In 845, Emperor Wuzong banned Buddhism in China. As part of the persecution, Foguang temple was burned to the ground, with only the Zushi pagoda surviving from the temple's early history.[4] Twelve years later in 857 the temple was rebuilt, with the Great East Hall being built on the former site of a three storey pavilion. A woman named Ning Gongyu provided most of the funds needed to construct the hall, and its construction was led by a monk named Yuancheng. In the 10th century, a depiction of Foguang Temple was painted in cave 61 of the Mogao Grottoes. However, it is likely the painters had never seen the temple, because the main hall in the painting is a two-storied white building with a green-glaze roof, very different from the red and white of the Great East Hall. This painting indicates that Foguang Temple was an important stop for Buddhist pilgrims.[5] In 1137 of the Jin dynasty, the Manjusri Hall was constructed on the temple's north side, along with another hall dedicated to Samantabhadra, which was burnt down in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912).[6][7]

In 1930, the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture began a search in China for ancient buildings. In the seventh year of the society's search in 1937, an architectural team led by Liang Sicheng discovered that Foguang Temple was a relic of the Tang Dynasty.[8] Liang was able to date the building after his wife found an inscription on one of the rafters.[9] The date's accuracy was confirmed by Liang's study of the building which matched with known information about Tang buildings.[10]

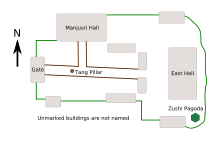

Layout

Unlike most other Chinese temples which are oriented in a south-north position, the Foguang temple is oriented in an east-west position due to there being mountains located on the east, north and south.[12] Having mountains behind a building is believed to improve its Feng Shui.[13] The temple consists of two main halls. The northern hall is called The Hall of Manjusri and was constructed in 1147 during the Jin dynasty. The largest hall, the Great East Hall was constructed in 857 during the Tang Dynasty.[14] Another large hall, known as the Samantabhadra Hall, once existed on the south side of the monastery but is no longer extant.[6]

Great East Hall

Dating from 857 of the Tang Dynasty, the Great East Hall (东大殿) is the third oldest dated wooden building in China after the main hall of the Nanchan Temple dated to 782, and the main hall of the Five Dragons Temple, dated to 831,[15][16] and the largest of the three. The hall is located on the far east side of the temple, atop a large stone platform. It is a single storey structure measuring seven bays by four or 34 by 17.7 metres (110 by 58 ft), and is supported by inner and outer sets of columns. On top of each column is a complicated set of brackets containing seven different bracket types that are one-second as high as the column itself.[17] Supporting the roof of the hall, each of the bracket sets are connected by crescent shaped crossbeams, which create an inner ring above the inner set of columns and an outer ring above the outer columns. The hall has a lattice ceiling that conceals much of the roof frame from view.[18] The hipped-roof and the extremely complex bracket sets are testament to the Great East Hall's importance as a structure during the Tang Dynasty.[17] According to the 11th-century architectural treatise, Yingzao Fashi, the Great East Hall closely corresponds to a seventh rank building in a system of eight ranks. The high rank of the Great East Hall indicates that even in the Tang Dynasty it was an important building, and no other buildings from the period with such a high rank survive.[18][19]

Inside the hall are thirty-six sculptures, as well as murals on each wall that date from the Tang Dynasty and later periods.[18][20] Unfortunately the statues lost much artistic value when they were repainted in the 1930s. The centre of the hall has a platform with three large statues of Sakyamuni, Amitabha and Maitreya sitting on lotus shaped seats. Each of the three statues is flanked by four assistants on the side and two bodhisattvas in front. Next to the platform, there are statues of Manjusri riding a lion as well as Samantabhadra on an elephant. Two heavenly kings stand on either side of the dais. A statue representing the hall's benefactor, Ning Gongwu and one of the monk who helped build the hall Yuancheng, are present in the back of the hall.[20] There is one large mural in the hall that shows events that took place in the Jataka, which chronicles Buddha's past life. Smaller murals in the temple show Manjusri and Samantabhadra gathering donors to help support the upkeep of the temple.[4]

Hall of Manjusri

On the north side of the temple courtyard is the Manjusri Hall (文殊殿).[2] It was constructed in 1137 during the Jin dynasty and is roughly the same size as the East Hall, also measuring seven bays by four. It is located on an 83 cm (2.7 ft) high platform, has three front doors and one central back door, and features a single-eave hip gable roof. The interior of the hall has only four support pillars. In order to support the large roof, diagonal beams are used.[21] On each of the four walls are murals of arhats painted in 1429 during the Ming dynasty.[2][22]

Zushi Pagoda

The Zushi Pagoda (祖师塔), is a small funerary pagoda located to the south of the Great East Hall. While it is unclear as to the exact date of its construction, it was either built during the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) or Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577) and possibly contains the tomb of the founder of the Foguang Temple.[23] It is a white, hexagonal shaped 6 metres (20 ft) tall pagoda. The first storey of the pagoda has a hexagonal chamber, while the second storey is purely decorative. The pagoda is decorated with lotus petals and the steeple supports a precious bottle in the shape of a flower.[24]

Funerary pillars

The temple grounds contain two Tang Dynasty funerary pillars. The oldest one, which 3.24 meters (10.6 ft) tall and hexagonal, was built in 857 to record the East Hall's construction.[4]

The present

Beginning in 2005, Global Heritage Fund (GHF), in partnership with Tsinghua University (Beijing), has been working to conserve the cultural heritage of Foguang Temple's Great East Hall. The hall has not had any restoration work done since the 17th century, and suffers from water damage and rotting beams.[25] Despite the temple undergoing restoration, it is still open to the public.[26] On June 26, 2009, the temple was inscribed as part of the Mount Wutai UNESCO World Heritage Site.[27]

Notes

- 'Discovered' in this context means that while the temple was known to local people, its importance was unknown to the academic community.

- Qin (2004), 342.

- Chai (1999), 83.

- "Foguang Temple Nomination File". UNESCO. 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- Steinhardt (2004), 237.

- Steinhardt (1997), 231.

- Chai (1999), 310.

- Steinhardt (2004), 228.

- Fairbank (1994), 96.

- Fairbank (1994), 95.

- Wei (2000), 143.

- Steinhardt (2004), 233.

- Bramble (2003), 115.

- Qin (2004), 335.

- Steinhardt (2004), 229–230.

- Steinhardt identifies some other buildings from the Tang Dynasty (not all of these are recognized by scholars as actually dating from the Tang Dynasty), but these do not have specific building dates associated with them, and can only be dated stylistically to a certain era.

- Steinhardt (2002), 116.

- Steinhardt (2004), 234.

- Steinhardt (2004), 239.

- Howard (2006), 373.

- Steinhardt (1997), 232.

- Chai (1999), 87.

- Qin (2004), 341–342.

- Lin (2004), 123.

- Global Heritage Fund (GHF) - Where We Work Archived 2011-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Harper (2009), 404.

- "China's sacred Buddhist Mount Wutai inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

References

- Bramble, Cate. Architect's Guide to Feng Shui: Exploding the Myth. Oxford: Elsevier, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7506-5606-1

- (in Chinese) Chai Zejun. Chai Zejun Gujianzhu Wenji. Beijing: Wenwu, 1999. ISBN 978-7-5010-1034-9

- Fairbank, Wilma. Liang and Lin: Partners in Exploring China's Architectural Past. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8122-3278-3

- Harper, Damian ed. China. London: Lonely Planet, 2009.

- Howard, Angela Falco, et al. Chinese Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-300-10065-5

- (in Chinese) Lin Zhu. Liang Sicheng: Linhuiyinyuwo. Lianjing, 2004 ISBN 978-957-08-2761-3

- (in Chinese) Qin Xuhua, ed. Dudong Wutaishan. Taiyuan: Shanxi People's Press, 2004. ISBN 7-203-05076-9

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman ed. Chinese Architecture. New Haven: Yale University, 2002. ISBN 978-0-300-09559-3

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. Liao Architecture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1997. ISBN 0-8248-1843-1

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History", The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254.

- Wei Ran. Buddhist Buildings: Ancient Chinese Architecture. Springer, 2000. ISBN 978-3-211-83030-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Foguang Temple. |