Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar

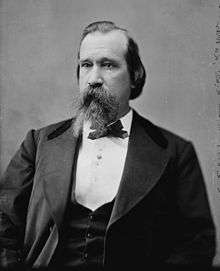

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II (September 17, 1825 – January 23, 1893) was an American politician, diplomat, and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Mississippi in both houses of Congress, served as the United States Secretary of the Interior, and was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He also served as an official in the Confederate States of America.

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 16, 1888 – January 23, 1893 | |

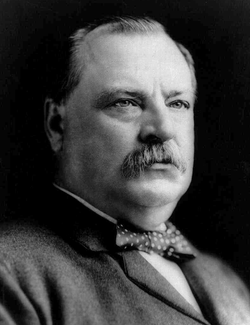

| Nominated by | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | William Woods |

| Succeeded by | Howell Jackson |

| 16th United States Secretary of the Interior | |

| In office March 6, 1885 – January 10, 1888 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | Henry Teller |

| Succeeded by | William Vilas |

| United States senator from Mississippi | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – March 6, 1885 | |

| Preceded by | James Alcorn |

| Succeeded by | Edward Walthall |

| Chairman of the House Democratic Caucus | |

| In office March 4, 1875 – March 3, 1877 | |

| Speaker | Michael C. Kerr (1875–1876) Samuel J. Randall (1876–1877) |

| Preceded by | William E. Niblack |

| Succeeded by | Hiester Clymer |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Mississippi's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1873 – March 3, 1877 | |

| Preceded by | George Harris |

| Succeeded by | Henry Muldrow |

| In office March 4, 1857 – December 20, 1860 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Wright |

| Succeeded by | Vacant 1860–1870; George Harris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 17, 1825 Eatonton, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | January 23, 1893 (aged 67) Vineville, Georgia, U.S. (now Macon) |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Father | Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar I |

| Education | Emory University (BA) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Born and educated in Georgia, he moved to Oxford, Mississippi to establish a legal practice. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1856 and served until December 1860, when he helped draft Mississippi's Ordinance of Secession. He helped raise the 19th Mississippi Infantry Regiment and worked on the staff of his wife's cousin, General James Longstreet. In 1862, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Lamar to the position of Confederate minister to Russia. Following the Civil War, Lamar taught at the University of Mississippi and was a delegate to several state constitutional conventions.

Lamar returned to the United States House of Representatives in 1873, becoming the first Mississippi Democrat elected to the House since the end of the Civil War. He remained in the House until 1877, and represented Mississippi in the Senate from 1877 to 1885. He opposed Reconstruction and voting rights for African Americans.[1][2] In 1885, he accepted appointment as Grover Cleveland's Secretary of the Interior. In 1888, the Senate confirmed Lamar's nomination to the Supreme Court, making Lamar the first Southerner appointed to the court since the Civil War. He remained on the court until his death in 1893.

Early life and career

Lamar was born at the family home of "Fairfield," near Eatonton, Putnam County, Georgia, the son of Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar and Sarah Williamson Bird. He was a cousin of future associate justice Joseph Lamar, and nephew of Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, second president of the Republic of Texas. In 1845 he graduated from Emory College (now Emory University), then located in Oxford, Georgia. He was a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity and was among the first initiates in that fraternity's chapter at the University of Mississippi.[3]

After graduating, Lamar married the daughter of Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, who moved to Oxford, Mississippi in 1849 to take the position of Chancellor at the recently established University of Mississippi. Lamar followed him and took a position as a professor of mathematics for a single year. He also practiced law in Oxford, eventually taking up the role of a planter, establishing a cotton plantation named Solitude in northern Lafayette County, near Abbeville.

In 1852, Lamar moved to Covington, Georgia, where he practiced law. He became involved with the Democratic Party and in 1853, he was elected to the Georgia State House of Representatives.

In 1855, he moved back to Mississippi where he purchased a plantation and many slaves.[4]

Congressional career and Civil War

In 1855, Lamar moved with his family back to Mississippi. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1856, beginning his service in 1857. When Mississippi declared that it had seceded from the U.S. and joined the Confederacy on January 9, 1861, Lamar said:

Thank God, we have a country at last: to live for, to pray for, and if need be, to die for.[5]

Lamar withdrew from the House in December 1860 to become a member in the Mississippi Secession Convention. Lamar drafted the state's Ordinance of Secession (see also Mississippi Ordinance of Secession). He considered a staff appointment to the new government, but abandoned that to co-operate with his former law partner, Christopher H. Mott in raising and supplying a regiment.

Lamar raised, and funded out of his own pocket, the 19th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Mott was commissioned colonel, as he had served as an officer in the war with Mexico, and Lamar was commissioned as lieutenant colonel. Lamar resigned his professorship in the university and was, on May 14, in Montgomery, offered his regiment to the Confederate War Department. On May 15, 1862, Colonel Lamar, while reviewing his regiment, fell with an attack of vertigo, which had previously disabled him; his service as a soldier was ended.

After this he served as a judge advocate and aide to his wife's cousin, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. Later in 1862, Confederate States President Jefferson Davis appointed Lamar as Confederate minister to Russia and special envoy to the United Kingdom and France. When the Civil War was over, he returned to the University of Mississippi where he was a professor of metaphysics, social science and law. In 1865, 1868, 1875, 1877, and 1881, he was also a member of Mississippi's constitutional conventions.

Later career

After having his civil rights restored following the war, Lamar returned to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1873, the first Democrat from Mississippi to be elected to the House since the Civil War. He served there until 1877. Lamar was elected by the state legislature (as was the practice at the time) to represent Mississippi in the U.S. Senate from 1877 to 1885. Lamar was a staunch opponent of Reconstruction, and did not consider freedmen and other black Americans fit to vote. He promoted "the supremacy of the unconquered and unconquerable Saxon race."[6]

Lamar served as United States Secretary of the Interior under President Grover Cleveland from March 6, 1885 to January 10, 1888. As part of the first Democratic administration in 24 years, and as head of the corrupt Interior Department rife with political patronage, Lamar was besieged by visitors seeking jobs. One day a visitor came who was not seeking a job and, as The New York Times later reported:

In the outer room were several prominent Democrats, including a high judicial officer, several Senators, and any number of members of the House. Mr. Lamar waved his visitor to a chair without saying a word. ... By and by his visitor said that he would go away and return at some other time, as he feared that he was keeping the people outside. "Pray sit still," requested Mr. Lamar. "You rest me. I can look at you, and you do not ask me for anything; and you keep those people out as long as you stay in."[7]

As secretary, Lamar removed the Department's fleet of carriages for its officials and used only his personal one-horse rockaway.

On December 6, 1887, President Cleveland nominated Lamar to be an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, filling the seat of the late William Burnham Woods.[8] Lamar was confirmed on January 16, 1888, making him the first justice of Southern origin appointed after the Civil War. (Woods, though appointed as a resident of Alabama, had been a native of Ohio and a Republican.)

He served on the court until his death. He died on January 23, 1893, in Vineville, Georgia. He is the only Mississippian to have served on the Supreme Court.

Lamar was originally interred at Riverside Cemetery in Macon, Georgia, but was reinterred at St. Peter's Cemetery in Oxford, Mississippi, in 1894.

Memorials and namesakes

During an 1884–85 Geological Survey, Geologist Arnold Hague named the East Fork of the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park the Lamar River in his honor. The Lamar Valley, or the Secluded Valley of trapper Osborne Russell and other park features or administrative names which contain Lamar are derived from this original naming in honor of Secretary of the Interior Lamar.[9]

Lamar Hall (1977) at the University of Mississippi in Oxford is named for him.

Lamar Avenue, a main thoroughfare in Oxford, Mississippi is also named for him.[10]

The L.Q.C. Lamar House in Oxford, MS designated in 1975 as a National Historic Landmark for its significance to "Political and Military Affairs 1865-1900." The house operates as a museum and the 3 acre grounds as a park.[11]

Lamar School in Meridian, MS is named for L.Q.C. Lamar.

The Lamar Bathhouse in Hot Springs National Park is named for him.

Legacy and honors

Three U.S. counties are named in his honor: Lamar County, Alabama; Lamar County, Georgia; and Lamar County, Mississippi, as well as communities in Wisconsin and Colorado. The Colorado community was named for him by the town fathers in the failed hope that he would designate it the home of the government mining office. Also named in his honor are at least two roadways: Lamar Blvd in Oxford and Lamar Avenue (US 78, and originally known as Pigeon Roost Road) in Memphis.[12]

Lamar was later featured in John F. Kennedy's Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Profiles in Courage (1957), for his eulogy speech for Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner (R) in 1874, along with his support of the findings of a partisan congressional committee regarding the disputed presidential election of 1876, and for his unpopular vote against the Bland–Allison Act of 1878.

Notes

- Mitchell, Dennis (2014). A New History of Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi. p. 162. ISBN 9781626741621.

Lamar told his audiences hat blacks were unfit to vote

- Teed, Paul (2015). Reconstruction: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 191. ISBN 9781610695336.

- Levere, Thomas. "A Paragraph History of Sigma Alpha Epsilon From The Founding of The Fraternity Until The Present Time". Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Cushman, Clare, ed. (2013). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–2012. SAGE Publications. p. 216. ISBN 9781608718337.

- The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns. Dir. Ken Burns, Narr. David McCullough, Writ. and prod. Ken Burns, PBS DVD Gold edition, Warner Home Video, 2002, ISBN 0-7806-3887-5.

- Lemann, Nicholas (2006). Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 96–97, 105, 151.

- "Justice Lamar's Death" (PDF). The New York Times. January 25, 1893. p. 8. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- U.S. Senate. "Supreme Court nominations: present-1789". Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Haines, Aubrey L. Yellowstone Place Names-Mirrors of History. Niwot, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-87081-382-X.

- https://mobile.nytimes.com/2017/08/09/us/ole-miss-confederacy.html

- http://www.lqclamarhouse.com/

- Christopher Blank (May 21, 2015). "More Memphis Streets Should Honor Great Musicians". WKNO-FM. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

References

- Edward Mayes, Lucius Q. C. Lamar: His Life, Times, and Speeches (Nashville, 1896)

- The Department of Everything Else: Highlights of Interior History (1989)

- Congressional Biography http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=L000030

- Senate summary of Profiles in Courage https://www.senate.gov/reference/common/generic/Profiles_LL.htm

- L.Q.C. Lamar. Letters, 1868–1885, photocopied. Clippings, one ALS (1874). 53 folders. University of Mississippi archives

- John F. Kennedy: Profiles in Courage.

- Thomas Lamar Coughlin, Those Southern Lamars ISBN 0-7388-2410-0

- James B. Murphy, "L. Q. C. Lamar: Pragmatic Patriot" (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 1973)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar (II). |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Works by or about Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar at Internet Archive

- Works by Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)