Taft Court

The Taft Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1921 to 1930, when William Howard Taft served as Chief Justice of the United States. Taft succeeded Edward Douglass White as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Taft served as Chief Justice until his resignation, at which point Charles Evans Hughes was nominated and confirmed as Taft's replacement. Taft was also the nation's 27th president (1909–13); he is the only person to serve as both President of the United States and Chief Justice.

| Taft Court | |

|---|---|

| |

| July 11, 1921 – February 3, 1930 (8 years, 207 days) | |

| Seat | Old Senate Chamber Washington, D.C. |

| No. of positions | 9 |

| Taft Court decisions | |

| |

The Taft Court continued the Lochner era and largely reflected the conservatism of the 1920s.[1] The Taft Court is also notable for being the first court able to exert some control over its own docket, as the Judiciary Act of 1925 instituted the requirement that almost all cases receive a writ of certiorari from four justices before appearing before the Supreme Court.[2]

Membership

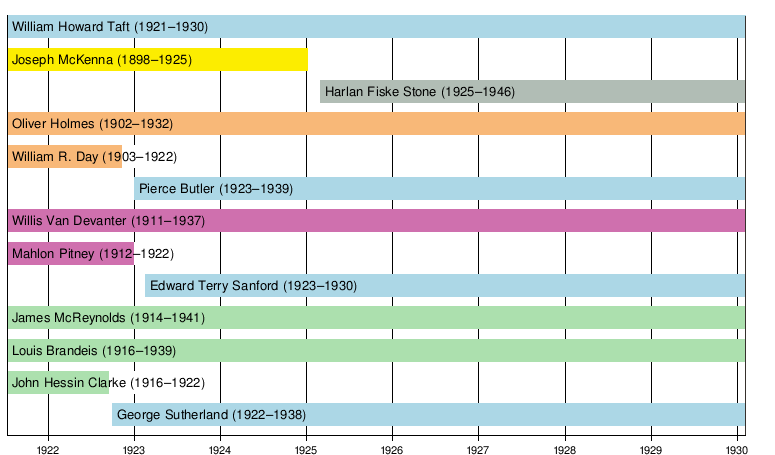

The Taft Court began in 1921 when President Warren Harding appointed former President William Howard Taft to replace Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, who Taft himself had made Chief Justice in 1910. The Taft Court began with Taft and eight members of the White Court: Joseph McKenna, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., William R. Day, Willis Van Devanter, Mahlon Pitney, James Clark McReynolds, Louis Brandeis, and John Hessin Clarke. In 1922 and 1923, Harding appointed George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, and Edward Terry Sanford to replace Day, Pitney, and Clarke. In 1925, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Harlan F. Stone to replace the retiring McKenna.

Timeline

Selected Rulings of the Court

- Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon (1922): In a decision written by Justice Holmes, the court established the doctrine of regulatory taking under the Takings Clause.

- Federal Baseball Club v. National League (1922): In a unanimous decision written by Justice Holmes, the court held that Major League Baseball operations did not qualify as interstate commerce and hence that the league was exempt from the Sherman Antitrust Act. The suit had been brought by the owner of the Baltimore Terrapins of the Federal League, the last major league to compete with Major League Baseball.

- Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. (1922): In an 8-1 decision delivered by Justice Taft, the court struck down the 1919 Child Labor Tax Law, which Congress had passed to tax companies using child labor. The court held that the tax was not a true tax, but rather a regulation on businesses using child labor, and thus a violation of the Tenth Amendment which the court held was charged with such regulation.

- Moore v. Dempsey (1923): In a 6-2 decision written by Justice Holmes, the court held that mob interference in a criminal trial violates due process, and that federal courts could protect against due process violations in trials held by state courts. It was the first Supreme Court case in the 20th century that protected the civil rights of African Americans in the South.[3]

- Adkins v. Children's Hospital (1923): In a 5-3 decision written by Justice Sutherland, the court struck down a national minimum wage law for women. The court held that minimum wage laws violate freedom of contract, a doctrine established in Lochner v. New York (1905). Adkins was overruled by West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937).

- Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925): In a unanimous decision written by Justice McReynolds, the court struck down the Oregon Compulsory Education Act, which had required children to attend only public schools; the law included several exceptions, and was mostly targeted at parochial schools. The court held that the law violated due process.

- Gitlow v. New York (1925): In a 7-2 decision written by Justice Sanford, the court held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment extended freedom of speech and freedom of the press protections of the First Amendment to the states. However, the court upheld the conviction of the defendant, socialist Benjamin Gitlow, on the basis that Gitlow's speech represented a danger to the country under the bad tendency test.[4] This was the first of several cases that incorporated the Bill of Rights.

- Carroll v. United States (1925): In a 7-2 decision written by Justice Taft, the court created the motor vehicle exception, which allows warrantless searches of automobiles.

- Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. (1926): In a 6-3 decision written by Justice Sutherland, the court upheld a local zoning measure as a valid use of police power. The court ruled that the local ordnance did not violate the Due Process Clause, as it was not discriminatory and had a rational basis.

- Buck v. Bell (1927): In an 8-1 decision written by Justice Holmes, the court upheld the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, a Virginia statute authorizing compulsory sterilization of the intellectually disabled at some state institutions.

- Olmstead v. United States (1928): In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Taft, the court upheld the conviction of Roy Olmstead and held that wiretapping private telephone conversations does not violate the Fourth Amendment or the Fifth Amendment. The case was overruled by Katz v. United States (1967).

Judicial philosophy

The Taft Court struck down numerous economic regulations in defense of a laissez faire economy, but largely avoided striking down laws that affected civil liberties.[5] The court struck down both federal and state regulations, with the latter often being struck down on basis of the dormant commerce clause.[6] The court also tended to take the side of businesses over unions, rarely intervened to protect minorities, and generally issued conservative rulings with regard to criminal procedure.[7] During the preceding White Court, progressives came close to taking control of the court, but Harding's appointments shored up the conservative wing.[5] Holmes and Brandeis (and Clarke, before his retirement) formed the progressive wing of the court and were more willing to uphold government regulations. McReynolds, Van Devanter, and the Harding appointees (Taft, Sutherland, Butler, and Sanford) made up the conservative bloc and frequently voted to strike down progressive legislation such as child labor laws.[5] Van Devanter, Taft, Sutherland, Butler, and Sanford formed a cohesive quintet that often voted together, while McReynolds was more likely than the others to dissent from the right.[8] McKenna was the lone centrist judge following the departures of Pitney and Day, though McKenna became more conservative as he neared retirement.[5] In 1925, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Attorney General Harlan F. Stone to replace McKenna, and Stone surprised many by aligning with Holmes and Brandeis.[9]

References

- Renstrom, Peter (2003). The Taft Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Galloway, Jr., Russell Wl (1 January 1985). "The Taft Court (1921-29)". Santa Clara Law Review. 25 (1): 21–22. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Galloway, Jr., 12

- Galloway, Jr., 19

- Galloway, Jr., 1-4

- Post, Robert (2002). "FEDERALISM IN THE TAFT COURT ERA: CAN IT BE "REVIVED"?". Duke Law Journal. 51 (5): 1606–1608. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Galloway, Jr., 47-48

- Galloway, Jr., 12-13

- Galloway, Jr., 16-17

Further reading

Works centering on the Taft Court

- Burton, David Henry (1998). Taft, Holmes, and the 1920s Court: An Appraisal. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838637685.

- Renstrom, Peter G. (2003). The Taft Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576072806.

Works centering on Taft Court judges

- Arkes, Hadley (1997). The Return of George Sutherland: Restoring a Jurisprudence of Natural Rights. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691016283.

- Rosen, Jeffrey (2016). Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300158670.

- Rosen, Jeffrey (2018). William Howard Taft. Times Books. ISBN 9781250293695.

- Slater, Stephanie L. (2018). Edward Terry Sanford: A Tennessean on the US Supreme Court. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781621903697.

- Urofsky, Melvin (2012). Louis D. Brandeis: A Life. Schocken Books. ISBN 9780805211955.

- White, G. Edward (1995). Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: Law and the Inner Self. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198024330.

Other relevant works

- Abraham, Henry Julian (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742558953.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. (1995). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L.; Ely, Jr., James W.; Grossman, Joel B., eds. (2005). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176612.

- Hall, Kermit L.; Ely, Jr., James W., eds. (2009). The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195379396.

- Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438108179.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles; Hoffer, WilliamJames Hull; Hull, N. E. H. (2018). The Supreme Court: An Essential History (2nd ed.). University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2681-6.

- Howard, John R. (1999). The Shifting Wind: The Supreme Court and Civil Rights from Reconstruction to Brown. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791440896.

- Irons, Peter (2006). A People's History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution (Revised ed.). Penguin. ISBN 9781101503133.

- Lendler, Marc (2012). Gitlow v. New York: Every Idea an Incitement. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1875-0.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Schwarz, Bernard (1995). A History of the Supreme Court. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195093872.

- Tomlins, Christopher, ed. (2005). The United States Supreme Court: The Pursuit of Justice. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618329694.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.