White Court (judges)

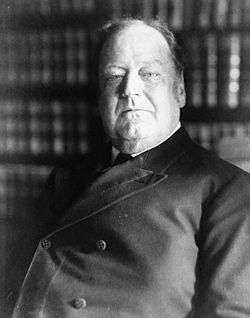

The White Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1910 to 1921, when Edward Douglass White served as Chief Justice of the United States. White, an associate justice since 1894, succeeded Melville Fuller as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and White served as Chief Justice until his death a decade later. He was the first sitting associate justice to be elevated to chief justice in the Court's history. He was succeeded by former president William Howard Taft.

| White Court | |

|---|---|

| |

| December 18, 1910 – May 19, 1921 (10 years, 152 days) | |

| Seat | Old Senate Chamber Washington, D.C. |

| No. of positions | 9 |

| White Court decisions | |

| |

The White Court was less conservative than the preceding Fuller Court, though conservatism remained a powerful force on the bench (and would remain so through the mid-1930s).[1] The most notable legacy of White's chief-justiceship was the development of the rule of reason doctrine, used to interpret the Sherman Antitrust Act, and foundational to United States antitrust law. During this era the Court also established that the Fourteenth Amendment protected the "liberty of contract." On the grounds of the Fourteenth Amendment and other provisions of the Constitution, it controversially overturned many state and federal laws designed to protect employees.

Membership

The White Court began in December 1910 when President William Howard Taft appointed White to succeed Melville Fuller as Chief Justice. White was the first Associate Justice to ascend to the position of Chief Justice.[2] Earlier in 1910, Taft had appointed Horace Harmon Lurton and Charles Evans Hughes to the Supreme Court. In 1911, Taft appointed Willis Van Devanter and Joseph Rucker Lamar to the court, filling vacancies that had arisen in 1910. The White Court thus began with the five Taft appointees and four veterans of the Fuller Court: John Marshall Harlan, Joseph McKenna, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and William R. Day. Harlan retired in 1911, and Taft appointed Mahlon Pitney to replace him. Lurton died in 1914, and President Woodrow Wilson appointed James Clark McReynolds to replace him.

In 1916, Lamar died and Hughes resigned to accept the Republican nomination for president. Wilson appointed Louis Brandeis and John Hessin Clarke to replace them. The White Court ended with White's death in 1921; President Warren G. Harding appointed Taft as White's successor.

Timeline

Rulings of the Court

- Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States (1911): In a decision written by Chief Justice White, the court upheld the government's prosecution of Standard Oil as valid under the Commerce Clause and the Sherman Antitrust Act. The decision resulted in the break-up of Standard Oil. United States v. American Tobacco Co. (1911) was decided on the same day for similar reasons, and led to the break-up of American Tobacco Company.

- Houston East & West Texas Railway Co. v. United States (1914): In a decision written by Justice Hughes, the court allowed the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate intrastate railroad rates, ruling that the ICC could regulate activity that has a "close and substantial relation" to interstate commerce.

- Guinn v. United States (1915): In a decision written by Chief Justice White, the court found grandfather clause exemptions to literacy tests to be unconstitutional. The court held that such clauses violated the Fifteenth Amendment, though Southern states continued to find ways to disenfranchise African-American voters.

- Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Co. (1916): In a decision written by Chief Justice White, the court upheld the federal income tax imposed by the Revenue Act of 1913.

- Selective Draft Law Cases (1918): In a decision written by Chief Justice White, the court upheld the Selective Service Act of 1917, which provided for conscription.

- Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918): In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Day, the court struck down the Keating–Owen Act, which sought to limit the use of child labor. The court held manufacturing itself does not constitute interstate commerce, and thus Congress did not have the power to regulate manufacturing conditions. Hammer was overruled by United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941).

- International News Service v. Associated Press (1918): In a decision written by Justice Pitney, the court formulated the misappropriation doctrine of federal intellectual property law. The case arose from the International News Service's copying of reports about World War I written by the Associated Press, and the court held that the AP reports qualified as quasi-property.

- Schenck v. United States (1919): In a decision written by Justice Holmes, the court upheld the Espionage Act of 1917 and the conviction of Charles Schenck, a socialist organizer who handed out leaflets urging draftees to refuse to serve in World War I. Holmes laid out the clear and present danger doctrine to determine what speech was not protected by the First Amendment. A similar case, Debs v. United States (1919), upheld the conviction of perennial socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs.

- Abrams v. United States (1919): In a decision written by Justice Clarke, the court upheld the Sedition Act of 1918 and the conviction of several defendants who had printed leaflets denouncing the American intervention in the Russian Civil War. In a dissenting opinion, Justice Holmes argued that the defendants did not present a clear and present danger, and also noted that the Sedition Act only applied to the First World War.

- Missouri v. Holland (1920): In a decision written by Justice Holmes, the court upheld the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which regulated the hunting of migratory waterfowl. The decision held that treaties take precedence over state law, and that the treaty did not violate the Tenth Amendment.

- United States v. Wheeler (1920): In a decision written by Chief Justice White, the court held that the Privileges and Immunities Clause establishes a right to travel.

- Newberry v. United States (1921): In a decision written by Justice McReynolds, the court overturned the conviction of Truman Handy Newberry and held that Congress has no authority to regulate the nominations processes of political parties. The decision struck down spending limits established by the Federal Corrupt Practices Act. The case stemmed from the 1918 Senate elections, in which Newberry defeated Henry Ford to win office as Senator from Michigan.

Judicial philosophy

Though the White Court continued to strike down some economic regulations and make conservative rulings, it was more open to such regulations than the other courts that preceded the New Deal.[1][3] The White Court issued several favorable rulings towards an expanded interpretation of the Commerce Clause and taxing powers, although Hammer stands as a notable exception.[3] The White Court also issued notable rulings in the wake of World War I, and the court generally ruled in favor of the government.[4] After the 1916 appointments, the court had three ideological wings: Holmes, Brandeis, and Clarke were the progressives, McKenna, White, Pitney, and Day were centrists, and McReynolds and Van Devanter were conservative.[1] Prior to his resignation, Hughes was often considered a progressive, while Lurton and Lamar did not serve long enough to develop strong ideological leanings.[5] Regardless of the ideological blocs, consensual norms and the high load of relatively mundane cases faced by the Supreme Court prior to the Judiciary Act of 1925 meant that many cases were decided unanimously.[6]

References

- Galloway, Jr., Russell Wl (1 January 1985). "The Taft Court (1921-29)". Santa Clara Law Review. 25 (1): 1–2. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Currie, David P. (1985). "THE CONSTITUTION IN THE SUPREME COURT: 1910-1921". Duke Law Journal. 34 (6): 1111. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Shoemaker, Rebecca (2004). The White Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 32–33. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- White, 147

- Wood, Sandra L. (Summer 1998). "The Supreme Court, 1888-1940: An Empirical Overview" (PDF). Social Science History. 22 (2): 206–207. doi:10.1017/s0145553200023269. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Wood, 204, 211-212

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry Julian (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742558953.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. (1995). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L.; Ely, Jr., James W.; Grossman, Joel B., eds. (2005). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195176612.

- Hall, Kermit L.; Ely, Jr., James W., eds. (2009). The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195379396.

- Hall, Timothy L. (2001). Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438108179.

- Highsaw, Robert B. (1999). Edward Douglass White: Defender of the Conservative Faith. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807124284.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles; Hoffer, WilliamJames Hull; Hull, N. E. H. (2018). The Supreme Court: An Essential History (2nd ed.). University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2681-6.

- Howard, John R. (1999). The Shifting Wind: The Supreme Court and Civil Rights from Reconstruction to Brown. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791440896.

- Irons, Peter (2006). A People's History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution (Revised ed.). Penguin. ISBN 9781101503133.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Pratt, Walter F. (1999). The Supreme Court Under Edward Douglass White, 1910-1921. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570033094.

- Schwarz, Bernard (1995). A History of the Supreme Court. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195093872.

- Shoemaker, Rebecca S. (2004). The White Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomlins, Christopher, ed. (2005). The United States Supreme Court: The Pursuit of Justice. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618329694.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- White, G. Edward (1995). Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: Law and the Inner Self. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198024330.