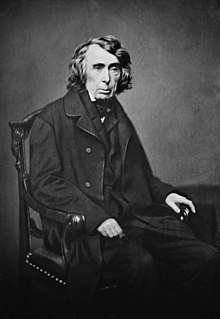

Peter Vivian Daniel

Peter Vivian Daniel (April 24, 1784 – May 31, 1860) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Peter Vivian Daniel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 10, 1842 – May 31, 1860[1] | |

| Nominated by | Martin Van Buren |

| Preceded by | Philip Barbour |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Miller |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia | |

| In office April 19, 1836 – March 3, 1841 | |

| Appointed by | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Philip Barbour |

| Succeeded by | John Mason |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Stafford County | |

| In office December 5, 1808 – December 3, 1810 | |

| Preceded by | John T. Brooke |

| Succeeded by | Charles Julian |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 24, 1784 Stafford County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | May 31, 1860 (aged 76) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Lucy Randolph

( m. 1808; died 1847)Elizabeth Harris

( m. 1850; died 1857) |

| Children | 5 |

| Education | Princeton University |

Early life, education, and career

Daniel was born in Stafford County, Virginia, in 1784 to Travers Daniel, a plantation owner, and Frances Moncure Daniel. He was educated at home by private tutors and entered the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) at the age of 18. He returned to Virginia after one year and subsequently studied law under former Virginia governor and U.S. attorney general Edmund Randolph. In 1808 he was admitted to the bar.[2]

Shortly after returning he entered into a conflict with a Fredericksburg businessman, John Seddon, which resulted in the parties agreeing to a duel. Since dueling was prohibited in Virginia, the Daniel-Seddon duel was fought in Maryland. The duel took place and Daniel wounded Seddon, who later died of his wound shortly after returning to Virginia. Daniel married Randolph's daughter, Lucy, two years later.

In 1809, Daniel was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, and in 1812 became a member of the advisory Virginia Privy Council. In 1818 he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, retaining his Council seat.[3] During the 1830s, he was a member of the Richmond Junto, a powerful element of the Jacksonian Democrats, and a strong supporter of both Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren. In 1830, he ran unsuccessfully for governor of Virginia.

Judicial service

Eastern District of Virginia

On April 6, 1836, Daniel was nominated by President Jackson to a seat on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia vacated by the elevation of Philip Pendleton Barbour to the Supreme Court. Daniel was confirmed by the United States Senate on April 19, 1836, and received his commission the same day.[4] While Daniel sat on the District Court he was against latitudinarian judicial constructs, or the practice of District Court Justices also riding the Circuit Court system.

Supreme Court

On February 26, 1841, Daniel was nominated by President Martin Van Buren, a Democrat, to serve as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, again to a seat vacated by Barbour (who had died). As Daniel's nomination to the Court came during the last week of the president's term (he succeeded on March 4, 1841 by William Henry Harrison of the Whig party) it was strongly opposed by Whigs in the Senate.[2] Nonetheless, he won Senate confirmation by a wide margin (25–5)[5] on March 2, 1841, and received his commission the following day.<FJC-PVD/> His actual service on the Supreme Court began on January 10, 1842, and ended May 31, 1860, upon his death.[6]

Daniel was the most frequent dissenter in the Taney Court with nearly two-thirds of his opinions going against the majority. Of the seventy-four opinions he wrote, fifty of them were dissents. His political views were extremely reactionary and made the other justices around him seem moderate in comparison. He was a supporter of slavery, arguably the largest of the Taney Court, and he disagreed with the amount of power that was given to the federal government. He authored only one significant opinion, West River Bridge Co. v. Dix, in his eighteen years. He sided with the majority in the 1857 case Dred Scott v. Sandford by writing a concurring opinion, in which he stated that "the African negro race never have been acknowledged as belonging to the family of nations."[7] He was also in Jones v. Van Zandt, and concurred with the majority in Prigg v. Pennsylvania which affirmed the legality of the Fugitive Slave Act. Daniel wrote:

Concurring entirely, as I do, with the majority of the court, in the conclusions they have reached relative to the effect and validity of the statute of Pennsylvania now under review, it is with unfeigned regret that I am constrained to dissent from some of the principles and reasonings which that majority, in passing to our common conclusions, have believed themselves called on to affirm.

Death

Daniel died on May 31, 1860, in Richmond, Virginia at the age of 76. He was preceded in death by his first wife Lucy Nelson Randolph who died in November 1847. He left behind his second wife, Elizabeth Harris, and five children.

References

- "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Smentkowski, Brian P. Smentkowski. "Peter Vivian Daniel: United States Jurist". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Peter V. Daniel, 1842-1860". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Daniel, Peter Vivian". Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Supreme Court Nominations: 1789–Present". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary of the Senate. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary of the Senate. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Daniel, Peter (1857). "Daniel, Peter V. (1784-1860) The opinion of Justice Peter V. Daniel of the United States Supreme Court in the famous Dred Scott case". The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

Further reading

- John Paul Frank, Justice Daniel Dissenting: A Biography of Peter V. Daniel, 1784-1860 (Harvard University Press 1964 ISBN 0-678-08028-3).

- Friedman, Leon, and Fred L. Israel. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court, 1789-1969, Their Lives and Major Opinions. Vol. 1. New York: Chelsea House in Association with Bowker, 1969.

- Abraham, Henry Julian. Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Clinton. New and Rev. Ed., [4th ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999).

- Huebner, Timothy S. The Taney Court Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2003.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Pub., 1994.

External links

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Philip Barbour |

Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia 1836–1841 |

Succeeded by John Mason |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1842–1860 |

Succeeded by Samuel Miller | |