Oxford, Mississippi

Oxford is a city in, and the county seat of, Lafayette County, Mississippi, United States. Founded in 1837, it was named after the British university city of Oxford in hopes of having the state university located there, which it did successfully attract.

Oxford, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| City of Oxford | |

University of Mississippi, aka "Ole Miss" | |

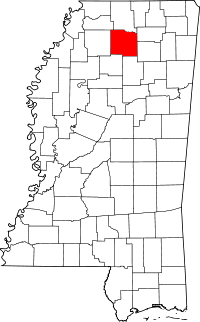

Location of Oxford, Mississippi | |

Oxford, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°21′35″N 89°31′34″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Lafayette |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Robyn Tannehill[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 26.71 sq mi (69.18 km2) |

| • Land | 26.62 sq mi (68.94 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.24 km2) |

| Elevation | 505 ft (154 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 18,916 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 28,122 |

| • Density | 1,056.54/sq mi (407.94/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | 38655 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-54840 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0691644 |

| Website | www |

As of the 2010 US Census, the population was 18,916;[4] the Census Bureau estimated the city's 2019 population at 28,122.[5] Oxford is the home of the University of Mississippi, founded in 1848, also commonly known as "Ole Miss".

History

Oxford and Lafayette County were formed from lands ceded by the Chickasaw people in the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek in 1832. The county was organized in 1836, and in 1837 three pioneers—John Martin, John Chisom, and John Craig—purchased land from Hoka, a female Chickasaw landowner, as a site for the town.[6] They named it "Oxford", intending to promote it as a center of learning in the Old Southwest. In 1841, the Mississippi legislature selected Oxford as the site of the state university, which opened in 1848.

During the American Civil War, Oxford was occupied by Union Army troops under Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman in 1862; in 1864 Major General Andrew Jackson Smith burned the buildings in the town square, including the county courthouse. In the postwar Reconstruction era, the town recovered slowly, aided by federal judge Robert Andrews Hill, who secured funds to build a new courthouse in 1872. During this period many African American freedmen moved from farms into town and established a neighborhood known as "Freedmen Town", where they built houses, businesses, churches and schools, and exercised all the rights of citizenship.[7] Even after Mississippi disenfranchised most African Americans in the 1890 Constitution of Mississippi, they continued to build their lives in the face of discrimination.

During the Civil Rights Movement, Oxford drew national attention in the Ole Miss protest of 1962. State officials, including Governor Ross Barnett, prevented James Meredith, an African American, from enrolling at the University of Mississippi, even after the federal courts had ruled that he be admitted. Following secret face-saving negotiations with Barnett, President John F. Kennedy ordered 127 U.S. Marshals, 316 deputized U.S. Border Patrol agents and 97 federalized Federal Bureau of Prisons officers to accompany Meredith.[8] Thousands of armed "volunteers" flowed into the Oxford area. Meredith traveled to Oxford under armed guard to register, but protests by segregationists broke out in opposition of his admittance. That night, cars were burned, federal law enforcement were pelted with rocks, bricks and small arms fire, and university property was damaged by 3,000 rioters. Two civilians were killed by gunshot wounds, and the protest spread into adjacent areas of the city of Oxford.[9] The protests were broken up on the campus with the early morning arrival of 3,000 nationalized Mississippi National Guard and federal troops, who camped in the city.[10]

More than 3,000 journalists came to Oxford on September 26, 2008, to cover the first presidential debate of 2008, which was held at the University of Mississippi.[11]

Geography

Oxford is in central Lafayette County in northern Mississippi, about 75 miles (121 km) south-southeast of Memphis, Tennessee.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 26.7 square miles (69.2 km2), of which 26.6 square miles (68.9 km2) are land and 0.1 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.35%, is water.[12] The campus of the University of Mississippi, west of downtown, is an unincorporated area surrounded by the city.

The city is located in the North Central Hills region of Mississippi. The region is known for its heavily forested hills made up of red clay. The area is higher and greater in relief than areas to the west (such as the Mississippi Delta or loess bluffs along the Delta), but lower in elevation than areas in northeast Mississippi. The changes in elevation can be noticed when traveling on the Highway 6 bypass, since the east-west highway tends to transect many of the north-south ridges. Downtown Oxford sits on one of these ridges and the University of Mississippi sits on another one, while the main commercial corridors on either side of the city sit in valleys.

Oxford is located at the confluence of highways from eight directions: Mississippi Highway 6 (now co-signed with US-278) runs west 25 miles (40 km) to Batesville and east 31 miles (50 km) to Pontotoc; Highway 7 runs north 30 miles (48 km) to Holly Springs and south 18 miles (29 km) to Water Valley. Highway 30 goes northeast 33 miles (53 km) to New Albany; Highway 334 ("Old Highway 6") leads southeast 19 miles (31 km) to Toccopola; Taylor Road leads southwest 9 miles (14 km) to Taylor; and Highway 314 ("Old Sardis Road") leads northwest, formerly to Sardis but now 11 miles (18 km) to the Clear Creek Recreation Area on Sardis Lake.

The streets in the downtown area follow a grid pattern with two naming conventions. Many of the north-south streets are numbered from west to east, beginning at the old railroad depot, with numbers from four to nineteen. The place of "Twelfth Street", however, is taken by North and South Lamar Boulevard (formerly North Street and South Street). The east-west avenues are named for the U.S. presidents in chronological order from north to south, from Washington to Cleveland; here again, there are gaps: there is no street for John Quincy Adams, who shares a last name with John Adams; "Polk Avenue" is replaced by University Avenue; and "Arthur Avenue" is lacking.

Oxford has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) and is in hardiness zone 7b.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 492 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,422 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,534 | 7.9% | |

| 1890 | 1,546 | 0.8% | |

| 1900 | 1,820 | 17.7% | |

| 1910 | 2,014 | 10.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,150 | 6.8% | |

| 1930 | 2,890 | 34.4% | |

| 1940 | 3,433 | 18.8% | |

| 1950 | 3,956 | 15.2% | |

| 1960 | 5,283 | 33.5% | |

| 1970 | 8,519 | 61.3% | |

| 1980 | 9,882 | 16.0% | |

| 1990 | 9,984 | 1.0% | |

| 2000 | 11,756 | 17.7% | |

| 2010 | 18,916 | 60.9% | |

| Est. 2019 | 28,122 | [3] | 48.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 1920-1930[14] | |||

As of the census[15] of 2010, there were 18,916 people, with 8,648 households residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 72.3% White, 21.8% African American, 0.3% Native American, 3.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, and 1.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.5% of the population. The average household size was 2.09.

The median income for a household in the city was $38,872, and the average household income was $64,643. The per capita income for the city was $29,195.[16] About 12% of families and 32.3% of the population were below the poverty line.

Arts and culture

Attractions

- The courthouse square, called "The Square", is the geographic and cultural center of the city. It features a confederate statue next to its courthouse, which was designed by the same architect that designed the statue in Holly Springs, Mississippi. It was erected in 1907.[17] The last person to be lynched in Oxford, around 1936, was dragged behind a car from "three-way", currently a four-way intersection on North Lamar, a prominent road which now is connected to Molly Bar, another prominent road in Oxford. The body of the lynched black man was then placed in the front window of a lawyer's office on the Square for several days to intimidate black Oxonians.

In addition to the historic Lafayette County Courthouse, the Square is known for an abundance of locally owned restaurants, specialty boutiques, and professional offices, along with Oxford City Hall.

- The J. E. Neilson Co., located on the southeast corner of the Square, is the South's oldest documented store. Founded as a trading post in 1839, Neilson's continues to anchor the Oxford square. Neilsons (pronounced Nelsons) was one of the few stores to survive the burning of Oxford during the Civil war. It stands within eyesight of one of Oxford's two confederate statues (one was erected after the original faced south because the South "never retreats;" a Falkner (William added a "U") paid for the second). Neilson's also features a letter from William Faulkner, who repeatedly refused to pay debts owed to the department store. When the Great Depression hit Oxford and most of the banks in town closed, Neilson's acted as a surrogate bank, cashing paychecks for university employees and others. Neilson's is also the only store in Oxford to carry supplies for Boy Scout uniforms.

- Square Books, founded in 1979, is an independent bookstore. A sister store, Off Square Books, is several doors down the street to the east. It deals in used and remainder books and is the venue for a radio show called Thacker Mountain Radio, with host Jim Dees, that is broadcast statewide on Mississippi Public Broadcasting. The show often draws comparisons to Garrison Keillor's A Prairie Home Companion for its mix of author readings and musical guests. A third store, Square Books Jr., deals exclusively in children's books and educational toys.

- The Lyric Theater, just off the courthouse square, is Oxford's largest music venue, with a capacity near 1200. Originally built in the late 1800s, the structure became a livery stable owned by William Faulkner's family in the early part of the 20th century. During the 1920s it became Oxford's first motion picture theater, the Lyric. In 1949, Faulkner walked from his home in Oxford to his childhood stable for the world premiere of MGM's Intruder in the Dust, adapted from one of his novels. The building housed office space and a health center from the early 1980s. After extensive restoration, the Lyric reopened on 3 July 2008 as a live music venue. It also is used occasionally for film and live drama.

- The Gertrude Castellow Ford Center for the Performing Arts on the University of Mississippi's campus hosts a broad range of events, such as symphony performances, operas, musicals, plays, comedy tours, chamber music, and guest lectures. The Ford Center, as it is commonly known, also hosted the 2008 Presidential Debate between former President Barack Obama and Senator John McCain.

- The University of Mississippi Museum is located on the University of Mississippi's main campus. The Robinson collection of Greek and Roman antiquities and the Millington-Barnard collection of 19th century scientific instruments are permanent collections of the museum. The museum is also home to the personal collections of Kate Skipwith and Mary Buie. The permanent exhibits are free to the public.[18]

- The Burns-Belfry Museum was previously the Burns Methodist Episcopal Church organized by freed African Americans in 1910. Now, the museum pays tribute to its role in the Civil War era. The museum houses a permanent exhibit on African American history that spans from slavery through the Civil Rights Movement.[19]

Culture

- Oxford has had a diverse music scene for many years. Oxford's relatively close proximity to large music cities such as Memphis, New Orleans, and Nashville, influence its musical stylings. Musicians past and present living in Oxford include Beanland, The Cooters, Bass Drum of Death, Kudzu Kings, Blue Mountain, George McConnell, Caroline Herring and blues harp player Adam Gussow.

- Oxford is also the home of the renegade blues label Fat Possum Records, who released records by blues legends R. L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough, as well as The Black Keys. Johnny Marr, former guitarist for The Smiths and current member of Modest Mouse bought a home in Oxford but no longer lives in it. Former Derek and the Dominos member Bobby Whitlock lived in Oxford where he had a ranch and his own studio.

- Musicians Modest Mouse, Gavin Degraw, Elvis Costello, The Hives, and Counting Crows have recorded albums at Sweet Tea Recording Studio in Oxford. Dennis Herring, the owner of Sweet Tea, has received Grammy awards for his work with artists such as Jars of Clay and blues great Buddy Guy.

- Bob Dylan wrote a song called "Oxford Town", which was included on his album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. The song was about the violent events surrounding the admission of James Meredith into the University of Mississippi in 1962. Dylan played a memorable concert at the Tad Smith Coliseum on the Ole Miss campus in November 1990, which opened with a performance of the song Oxford Town.

- Oxford has been the setting for numerous movies, including Intruder in the Dust (1949, based on the Faulkner novel), Home from the Hill (1960), Barn Burning (1980, based on the Faulkner short story), Rush (1981 documentary), Heart of Dixie (1989), The Gun in Betty Lou's Handbag (1992), Glorious Mail (2005), Sorry, We're Open (2008 documentary), The Night of the Loup Garou (2009), Where I Begin (2010), and parts of The People vs. Larry Flynt (1997).

- American journalist and novelist Joan Didion mentions Oxford in her collection of essays The White Album (book).[20]

Historic sites

See also National Register of Historic Places listings in Lafayette County, Mississippi[21] and the Lyceum-The Circle Historic District, University of Mississippi.

- Ammadelle (Pegues House), designed by Calvert Vaux

- Barnard Observatory (Center for the Study of Southern Culture), University of Mississippi, 1859

- Isom Place, ca. 1843, remodeled 1848

- Lafayette County Courthouse, 1872, designed by Willis, Sloan, and Trigg

- Lucius Q. C. Lamar House, ca. 1860

- The Lyceum, University of Mississippi, 1848, designed by William Nichols

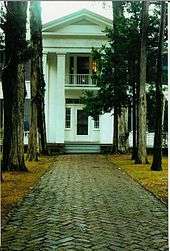

- Rowan Oak (William Faulkner House), 1848

- St. Peter's Episcopal Church, 1860, attributed to Richard Upjohn (Neo-Gothic)

- University of Mississippi Power House, site of William Faulkner's composition of As I Lay Dying

- Ventress Hall, University of Mississippi, 1889 (Richardson Romanesque)

Education

The city is served by two public school districts, Oxford School District and Lafayette County School District, and by three private schools: Oxford University School, Regents School of Oxford[22] and Magnolia Montessori. Oxford is partially the home of the main campus of the University of Mississippi, known as "Ole Miss" (much of the campus is in University, Mississippi, an unincorporated enclave surrounded by the city), and of the Lafayette-Yalobusha Center of Northwest Mississippi Community College. The North Mississippi Japanese Supplementary School, a Japanese weekend school, is operated in conjunction with the University of Mississippi, with classes held on campus.[23][24]

Media

Infrastructure

Health care

The Baptist Memorial Hospital - North Mississippi, located in Oxford provides comprehensive health care services for Oxford and the surrounding area, supported by a growing number of physicians, clinics and support facilities. The North Mississippi Regional Center, a state-licensed Intermediate Care Facility for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities (ICF/IID), is located in Oxford.

Oxford is home to the National Center for Natural Products Research at the University of Mississippi's School of Pharmacy. The Center is the only facility in the United States that is federally licensed to cultivate marijuana for scientific research, and to distribute it to medical marijuana patients.

Transportation

The city operates public transportation under the name Oxford-University Transit (OUT), with bus routes throughout the city and University of Mississippi campus.[27] Ole Miss students and faculty ride free upon showing University identification.

Mississippi Central Railroad provides freight rail service to the Lafayette County Industrial Park in Oxford.

University-Oxford Airport is a public use airport located two nautical miles (4 km) northwest of the central business district of Oxford. The airport is owned by the University of Mississippi.

Notable people

- William Faulkner grew up in Oxford and used it as the fictional city of "Jefferson".

- Authors include John Grisham, Kiese Laymon, Curtis Wilkie, Ace Atkins, Chris Offutt, Howard Bahr, Richard Ford, Tom Franklin, Beth Ann Fennelly, Ann Fisher-Wirth, Wright Thompson, Stark Young, Larry Brown, Willie Morris and Barry Hannah.

- Artists include photorealist painter Glennray Tutor, figurative painter Jere Allen and primitive artist Theora Hamblett (1895–1977).

- Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson (1810–1885) owned a manor called "Home Place" in Oxford that was burned during the Civil War by Union troops. A historical marker stands where it once stood.

- L.Q.C. Lamar (1825–1893), U.S. senator and supreme court justice, resided in Oxford, where he served as professor of mathematics at the University of Mississippi, farmed, and practiced law. He was the son-in-law of university chancellor Augustus Baldwin Longstreet. Lamar's home in Oxford was restored as a museum in 2008.

- Naomi Sims (1948-2009), fashion model, was born in Oxford.

- New York Giants quarterback Eli Manning, who played college football at Ole Miss, lives in Oxford during the off-season. His father, former Ole Miss and New Orleans Saints quarterback Archie Manning, owns a condominium in Oxford.

Sister city

References

- "Tannehill becomes Mayor". Oxfordeagle.com. June 29, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Total Population: 2010 Census DEC Summary File 1 (P1), Oxford city, Mississippi". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Jack Lamar Mayfield. Oxford and Ole Miss. Arcadia Publishing, 2009, p. 7.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-08-05. Retrieved 2008-06-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- U.S. Marshals Mark 50th Anniversary of the Integration of ‘Ole Miss’

- Doyle, William. An American Insurrection: James Meredith and the Battle of Oxford, Mississippi, 1962. New York: Anchor Books, 2003.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "2008 Presidential Debate | The University of Mississippi - Official Home Page". Debate.olemiss.edu. 2008-09-26. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- "U.S. Gazetteer Files: 2019: Places: Mississippi". U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Oxford, MS Household Income Statistics. CLRSearch. Retrieved on 2013-08-17.

- "Confederate statues in Oxford, Mississippi—Monuments to the dead or to white supremacy?". Oxfordeagle.com. September 27, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "University Museum —". Museum.olemiss.edu. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "Untitled Document". Burns-belfry.com. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- Didion, Joan. The white album (Paperback [reissue]ition ed.). ISBN 0374532079.

- Thomas S. Hines (1997). William Faulkner and the Tangible Past : The Architecture of Yoknapatawpha. University of California Press.

- "Regents School of Oxford". Regents School of Oxford. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Japanese Supplementary School." OGE-US Japan Partnership, University of Mississippi. Retrieved on February 25, 2015.

- "周辺案内." North Mississippi Japanese Supplementary School at The University of Mississippi. Retrieved on April 1, 2015.

- http://www.oxfordeagle.com/index.html

- http://www.thelocalvoice.net/

- "Oxford-University Transit". Oxfordms.net. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- Schnugg, Alyssa. ""Sister Cities"". Oxford Eagle. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oxford, Mississippi. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Oxford. |