Edward Douglass White

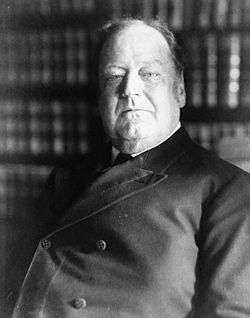

Edward Douglass White Jr. (November 3, 1845 – May 19, 1921), was an American politician and jurist from Louisiana. He was a United States Senator and the ninth Chief Justice of the United States. He served on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1894 to 1921. He is best known for formulating the Rule of Reason standard of antitrust law.

Edward Douglass White | |

|---|---|

| |

| 9th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office December 19, 1910 – May 19, 1921[1] | |

| Nominated by | William H. Taft |

| Preceded by | Melville Fuller |

| Succeeded by | William H. Taft |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office March 12, 1894 – December 18, 1910[1] | |

| Nominated by | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | Samuel Blatchford |

| Succeeded by | Willis Van Devanter |

| United States senator from Louisiana | |

| In office March 4, 1891 – March 12, 1894 | |

| Preceded by | James Eustis |

| Succeeded by | Newton Blanchard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Edward Douglass White Jr. November 3, 1845 Thibodaux, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | May 19, 1921 (aged 75) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Leita Montgomery ( m. 1894)Virginia Montgomery Kent |

| Education | Mount St. Mary's University (BA) Georgetown University (MA) Tulane University (LLB) |

Born in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana, White practiced law in New Orleans after graduating from the University of Louisiana. His father, Edward Douglass White Sr., was the 10th Governor of Louisiana and a Whig US Representative. White fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War, and was captured in 1865. After the war, White won election to the Louisiana State Senate and served on the Louisiana Supreme Court. As a member of the Democratic Party, White represented Louisiana in the United States Senate from 1891 to 1894.

In 1894, President Grover Cleveland appointed White as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. In 1910, President William Howard Taft elevated him to the position of Chief Justice. The appointment surprised many contemporaries, as Taft was a member of the Republican Party. White served as Chief Justice until his death in 1921, when he was succeeded by Taft.

He sided with the Supreme Court majority in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld the legality of state segregation to provide "separate but equal" public facilities in the United States, despite protections of the Fourteenth Amendment to equal protection of the laws. In one of several challenges to Southern states' grandfather clauses, used to disfranchise African-American voters at the turn of the century, he wrote for a unanimous court in Guinn v. United States, which struck down many Southern states' grandfather clauses. He also wrote the opinion in the Selective Draft Law Cases, which upheld the constitutionality of conscription.

Early life and education

White was born in 1845 in his parents' plantation house, now known as the Edward Douglass White House, near the town of Thibodauxville (now Thibodaux) in Lafourche Parish in south Louisiana.[2] He was the son of Edward Douglass White Sr., a former governor of Louisiana, and Catherine Sidney Lee (Ringgold).[3] He was a grandson of Dr. James White, a U.S. representative, physician, and judge.

On his mother's side, he was the grandson of Tench Ringgold, appointed as a U.S. marshal of the District of Columbia under the James Monroe and Andrew Jackson administrations. He was also related on his maternal side to the Lee family of Virginia. The White family's large plantation in Louisiana was based on cultivating and processing for market sugar cane, depending on the extensive labor of slaves.

White's paternal ancestors were of Irish Catholic descent, and he was reared in that religion, a devout Roman Catholic his entire life. He studied first at the Jesuit College in New Orleans, then at Mount St. Mary's College near Emmitsburg, Maryland. Last, he attended Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., where he was a member of the Philodemic Society. After the American Civil War, he returned to academic work and studied law at the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University) in New Orleans.

Confederate soldier

White's studies at Georgetown were interrupted by the Civil War. It has been suggested that he returned to Bayou Lafourche, enlisted in the Confederate States Army, and served under General Richard Taylor, eventually attaining the rank of lieutenant. This is questionable , as his widowed mother had remarried and was living with the rest of the family in New Orleans at the time. When he returned to Louisiana, it was probably to his primary home in New Orleans.

An apocryphal account states that White was almost captured by Union troops near Bayou Lafourche in October 1862, but that he evaded capture by hiding beneath hay in a barn. It is possible that White enlisted in the Lafourche Parish militia, as its muster rolls are not complete. There is no documentation, however, that White served in any Confederate volunteer unit or militia unit engaged in campaigns in the Lafourche area.

Another account suggests that he was assigned as an aide to Confederate General William Beall and accompanied him to Port Hudson, Louisiana, which was besieged and captured by Union troops in 1863. White's presence at Port Hudson, when he was 18 years old, is supported by a secondhand account of a postwar dinner conversation he had with Senator Knute Nelson of Minnesota, a Union veteran of Port Hudson, and another recounted by Admiral George Dewey (then a Federal naval officer at Port Hudson), in both of which White referred to being part of the besieged forces. But White's name does not appear on any list of prisoners captured at Port Hudson. According to another account of questionable reliability, White was supposedly sent to a Mississippi prisoner of war camp. (As practically all Confederate soldiers of enlisted rank of the Port Hudson garrison were paroled, and officers sent to prison in New Orleans and later to Johnson's Island, Ohio, this account is likely not true.) When White was paroled, he supposedly returned to the family plantation to find it abandoned, the canefields barren, and the place nearly empty of most former slaves.

The only "hard" evidence of White's Confederate service consists of an account of his capture on March 12, 1865 in an action in Morganza in Pointe Coupee Parish, which is contained in the Official Records of the American Civil War, and his service records in the National Archives, documenting his subsequent imprisonment in New Orleans and parole in April 1865. These records confirm his service as a lieutenant in Captain W. B. Barrow's company of a Louisiana cavalry regiment, for all practical purposes a loosely organized band of irregulars or "scouts" (guerrillas). One organizing officer of this regiment, which was sometimes called "Barrow's Regiment" or the "9th Louisiana Cavalry Regiment," was Major Robert Pruyn. Pruyn (a postwar mayor of Baton Rouge, Louisiana) served as courier relaying messages from Port Hudson's commander, General Franklin Gardner, to General Joseph E. Johnston, crossing the Union siege lines by swimming the Mississippi. Pruyn escaped from Port Hudson prior to its surrender in the same manner. According to another account, after White was paroled in April 1865 and following the surrender of the western Confederate forces, he ended his military career by walking (his clothing in rags) to a comrade's family home in Livonia in Pointe Coupee Parish.

White's Civil War service was taken as a matter of common knowledge at the time of his initial nomination to the United States Supreme Court, and the Confederate Veteran periodical, published for the United Confederate Veterans, congratulated him upon his confirmation. White was one of three ex-Confederate soldiers to serve on the Supreme Court. The others were Associate Justices Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar of Mississippi and Horace Harmon Lurton of Tennessee. The Court's other ex-Confederate, Associate Justice Howell Edmunds Jackson, had held a civil position under the Confederate government.

During the Reconstruction era, White was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Later, while on the Supreme Court, he approved of the film The Birth of a Nation, which helped reignite the Klan in the 1920s.[4]

In 1877, White served on the Reception Committee of the Knights of Momus in New Orleans. The Knights' Mardi Gras parade was an attack on Reconstruction so extreme that it was widely condemned, and even denounced by the Krewe of Rex.[5]

Political career

While living on his family's abandoned plantation, White began his legal studies. He enrolled at the University of Louisiana in New Orleans to complete his study of the law, at what is now known as the Tulane University Law School. He subsequently was admitted to the bar and commenced practice in New Orleans in 1868. He was also mentored as a young attorney by Edouard Bermudez, a New Orleans lawyer who later served as Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court.[6]

White served in the Louisiana State Senate in 1874,[7] a year marked by interracial violence in political campaigns and elections. He also served on the Louisiana Supreme Court from 1878 to 1880.[7] In 1891, the State Legislature elected him to the United States Senate[7] to succeed James B. Eustis. During his time in state politics White was politically affiliated with two-time governor Francis T. Nicholls (1876–1880; 1888–1892), a former Confederate general.

United States Supreme Court

Associate justice

White was nominated by President Grover Cleveland to be an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States in February 1894, after the failed nominations of William B. Hornblower and Wheeler Hazard Peckham. In contrast to those nominations, White's was approved by the U.S. Senate the same day it was received, and on March 12, 1894 he took the judicial oath of office.[1][7]

In 1896 White was a part of the 7–1 majority in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation laws for public facilities as long as the segregated facilities were "equal in quality."

Chief justice

President William Howard Taft nominated White to the position of Chief Justice of the United States in December 1910[7] following the death of Melville Fuller. Although White had served for sixteen years on the Court, the appointment was controversial, first because White was a Democrat while Taft was a Republican, and second because White was the first incumbent associate justice to be appointed as chief justice. (John Rutledge, a former associate justice, had been given a recess appointment as chief justice in 1795). Nonetheless, his selection was quickly confirmed by the U.S. Senate, and he took the judicial oath of office on December 19, 1910.[1]

White was generally seen as one of the more conservative members of the court. He originated the term, the "Rule of Reason." But, White also wrote the 1916 decision upholding the constitutionality of the Adamson Act, which mandated a maximum eight-hour work day for railroad employees.

As chief justice at a time when the Court's work was carried out with more than 8,000 cases brought each year before the court, and only a few clerks to work for all the members of the Court, the Chief Justice held weekly meetings with fellow jurists, assigned all the cases and wrote the majority opinions in 711 cases, as well as 155 dissenting opinions, all opposing income taxes. White wrote for a unanimous Court in Guinn v. United States (1915), which invalidated the Oklahoma and Maryland grandfather clauses (and, by extension, those in other Southern states) as "repugnant to the Fifteenth Amendment and therefore null and void."[8] But, Southern states quickly devised other methods to continue their disfranchisement of blacks (and in some cases, many poor whites) that withstood Court scrutiny.

In 1918, the Selective Draft Law Cases upheld the Selective Service Act of 1917, and more generally, upheld conscription in the United States, which President Taft said was "one of his great opinions."[8]

During his tenure as chief justice, White swore in presidents Woodrow Wilson (twice) and Warren G. Harding. At the time of his death on May 21, 1921, he had served on the Court for a total of 26 years, 10 of them as chief justice. He was the last serving Supreme Court Justice appointed by President Cleveland. He was succeeded by former president Taft, who had himself long-desired the chief justiceship, thus making White the only chief justice to be followed in office by the president who appointed him.

Marriage and family

White married Leita Montgomery Kent, the widow of Linden Kent, on November 6, 1894, in New York City.[9]

Death

White died on May 19, 1921, at the age of 75.[7] Buried initially at the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C., the Supreme Court Historical Society reports that his body was transferred after 14 years to Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio.[10]

Legacy and honors

- In 1914, he was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, the oldest and most prestigious award for American Catholics.[11]

- A statue of White is one of the two honoring Louisiana natives in the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol.

- A statue of White is located in front of the Louisiana Supreme Court building in New Orleans. The second statue is a local landmark on the New Orleans scene, created by Bryant Baker, who was selected for the commission by White's widow, and dedicated April 8, 1926.[12] "Big Green Ed", as his likeness is often referred to, is a favorite of locals and tourists alike. Visitors are often seen sitting at the base of his likeness, discussing issues of the day. Moreover, local custom holds that those who run around the statue in a counterclockwise direction will not be arrested that night.

- In his honor, the Louisiana State University Law Center founded the annual Edward Douglass White Lectures. They have featured such distinguished speakers as Chief Justices Warren E. Burger and William H. Rehnquist.

- The play, Father Chief Justice: Edward Douglass White and the Constitution by Paul Baier, a professor at LSU Law Center, was based on White's life.

- In 1995, White was posthumously inducted into the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame in Winnfield.

- Edward Douglass White Council #2473 of the Knights of Columbus in Arlington, Virginia, was named in his honor, but dropped the name in August 2020.[13]

- The Chief Justice White Council #2586 of the Knights of Columbus in Bogota, New Jersey, is also named in his honor.[14]

- Edward Douglas White Catholic High School in Thibodaux, Louisiana, was named for him.

- During World War II the Liberty ship SS Edward D. White was built in Brunswick, Georgia, and named in his honor.[15]

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the White Court

References

- "Justices 1789 to Present". www.supremecourt.gov. Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- George R. Adams and Ralph Christian (April 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Edward Douglass White House / Edward Douglass White Louisiana State Commemorative Area" (pdf). National Park Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The First Century of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1965. Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y, 1965., p. 27

- New Orleans newspaper The Republican, February 14, 1877.

- "Edouard Edmund Bermudez (1832-1892)". Louisiana Supreme Court. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Edward Douglass White, 1910-1921". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Delehant, John W. (December 1967). "A Judicial Revisitation Finds Kneedler v. Lane Not So 'Amazing'". ABA Journal. 53: 1132.

- Chadwick, Georgia (Spring 2008). "Looking Out on Royal Street" (PDF). De Novo, the newsletter of the Law Library of Louisiana. 6 (1): 6–8. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- Christensen, George A. (1983). "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices". Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook 1983. Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- "Recipients | The Laetare Medal". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Statue to White Will be Unveiled to Ceremonies." The Times-Picayune (March 4, 1926): p. 6.

- "Edward Douglass White Council #2473". Arlington Virginia: Knights of Columbus. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- "Chief Justice White #2586". West Orange, New Jersey: New Jersey State Council, Knights of Columbus. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Williams, Greg H. (July 25, 2014). The Liberty Ships of World War II: A Record of the 2,710 Vessels and Their Builders, Operators and Namesakes, with a History of the Jeremiah O'Brien. McFarland. ISBN 1476617546. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- United States Congress. "Edward Douglass White (id: W000366)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-04-11

- "Chief Justice White Is Dead at Age 75 After an Operation." The New York Times. May 19, 1921

- Floyd, William Barrow, The Barrow Family of Old Louisiana, (Transylvania Printing Co., Lexington, Ky., 1963)

- Highsaw, Robert B. (1981) Edward Douglass White: Defender of the Conservative Faith, Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1ISBN 0807124281.

- Klinkhammer, Marie. (1943) Edward Douglass White, Chief Justice of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press.

- Pratt, Walter F. (1999) The Supreme Court Under Edward Douglass White, 1910–1921. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-309-9.

- Reeves, William D., Paths to Distinction: Dr. James White, Governor E.D. White and Chief Justice Edward Douglass White of Louisiana. Thibodaux, La., 1999: Friends of the Edward Douglass White Historic Site. ISBN 1-887366-33-4.

- The White Court, 1910-1921, History of the Court, Supreme Court Historical Society.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cassidy, Lewis C. (1923) Life of Edward Douglass White: Soldier, Statesman, Jurist, 1845-1921. Ph.D. dissertation, Georgetown University.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.*The White Court, 1910-1921, History of the Court, Supreme Court Historical Society.

- Finkelman, Paul. "White, Edward Douglass"; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000. Access Oct 05 2016

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Mele, Joseph C. (Fall 1962) Edward Douglass White's Influence on the Louisiana Anti-Lottery Movement. Southern Speech Journal 28: 36-43.

- Miller, William Timothy. (1933)Edward Douglass White: A Study in Constitutional History. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University.

- Ramke, Diedrich. (1940) Edward Douglass White —- Statesman and Jurist. Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.

- Reeves, William Dale. (1999) Paths to distinction: Dr. James White, Governor E.D. White, and Chief Justice Edward Douglass White of Louisiana. Friends of the Edward Douglass White Historic Site. ISBN 1-887366-33-4

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- U.S. Supreme Court. (1921) Proceedings of the Bar and Officers of the Supreme Court of the United States in Memory of Edward Douglass White, December 17, 1921. Washington: Government Printing Office.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edward Douglass White |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Douglass White. |

- Ariens, Michael, Edward Douglass White.

- Bust of Edward Douglass White, Oyez. official Supreme Court media.

- The E. D. White Historic Site, including the original plantation home, operated by the Louisiana State Museum

- Edward Douglas White, official Supreme Court media, Oyez.

- Edward Douglass White at Find a Grave

| U.S. Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Eustis |

U.S. senator (Class 3) from Louisiana 1891–1894 Served alongside: Randall Gibson, Donelson Caffery |

Succeeded by Newton Blanchard |

| Preceded by John P. Jones |

Chair of the Senate Contingent Expenses Audit Committee 1893–1894 |

Succeeded by Johnson N. Camden |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by Samuel Blatchford |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1894–1910 |

Succeeded by Willis Van Devanter |

| Preceded by Melville Fuller |

Chief Justice of the United States 1910–1921 |

Succeeded by William Taft |