List of tsunamis

This article lists notable tsunamis, which are sorted by the date and location that the tsunami occurred.

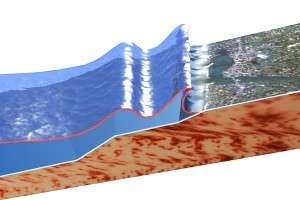

Because of seismic and volcanic activity associated with tectonic plate boundaries along the Pacific Ring of Fire, tsunamis occur most frequently in the Pacific Ocean, but are a worldwide natural phenomenon. They are possible wherever large bodies of water are found, including inland lakes, where they can be caused by landslides and glacier calving. Very small tsunamis, non-destructive and undetectable without specialized equipment, occur frequently as a result of minor earthquakes and other events.

Around 1600 BC, a tsunami caused by the eruption of Thira devastated the Minoan civilization on Crete and related cultures in the Cyclades, as well as in areas on the Greek mainland facing the eruption, such as the Argolid.

The oldest recorded tsunami occurred in 479 BC. It destroyed a Persian army that was attacking the town of Potidaea in Greece.[1]

As early as 426 BC, the Greek historian Thucydides inquired in his book History of the Peloponnesian War (3.89.1–6) about the causes of tsunamis. He argued that such events could only be explained as a consequence of ocean earthquakes, and could see no other possible causes.[2]

Prehistoric

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≈1.4 Ma | Molokai, Hawaii | East Molokai Volcano | Landslide | A third of the East Molokai Volcano collapsed into the Pacific Ocean, generating a tsunami with an estimated local height of 2,000 feet (610 m). The wave traveled as far as California and Mexico.[3][4][5] |

| ≈7000–6000 BC | Lisbon, Portugal | Unknown | A series of giant boulders and cobbles have been found 14 m above mean sea level near Guincho Beach.[6] | |

| ≈6225–6170 BC | Norwegian Sea | Storegga Slide | Landslide | The Storegga Slide(s), 100 km north-west of the Møre coast in the Norwegian Sea, caused a large tsunami in the North Atlantic Ocean. The collapse involved ~290 km of coastal shelf, and a total volume of 3,500 km3 of debris.[7] Based on carbon dating of plant material from sediment deposited by the tsunami, the latest incident occurred around 6225–6170 BC.[8][9] In Scotland, traces of the tsunami have been found in sediment from Montrose Basin, the Firth of Forth, up to 80 km inland and 4 metres above current normal tide levels. |

| 5,500 BP | Northern Isles | Garth tsunami | Tsunami of unknown origin | The tsunami may be responsible for contemporaneous mass burials.[10] |

| ≈1600 BC | Santorini, Greece | Minoan eruption | Volcanic eruption | The volcanic eruption on Santorini, Greece is assumed to have caused severe damage to cities around it, most notably the Minoan civilization on Crete. A tsunami is assumed to be the factor that caused the most damage. |

Before 1001 CE

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 479 BC | Potidaea, Greece | 479 BC Potidaea tsunami | The earliest recorded tsunami in history.[1] During the Persian siege of the sea town Potidaea, Greece, Herodotus reports how Persian attackers who tried to exploit an unusual retreat of the water were suddenly surprised by "a great flood-tide, higher, as the people of the place say, than any one of the many that had been before". Herodotus attributes the cause of the sudden flood to the wrath of Poseidon.[11] | |

| 426 BC | Malian Gulf, Greece | 426 BC Malian Gulf tsunami | In the summer of 426 BC, a tsunami hit the gulf between the northwest tip of Euboea and Lamia.[12] The Greek historian Thucydides (3.89.1–6) described how the tsunami and a series of earthquakes affected the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) and, for the first time, associated earthquakes with waves in terms of cause and effect.[13] | |

| 373 BC | Helike, Greece | Earthquake | An earthquake and a tsunami destroyed the prosperous Greek city of Helike, 2 km from the sea. The fate of the city, which remained permanently submerged, was often commented upon by ancient writers[14] and may have inspired the contemporary Plato to the myth of Atlantis. | |

| 60 BC | Portugal and Galicia | Earthquake | An earthquake of intensity IX and an estimated magnitude of 6.7 caused a tsunami along the coasts of Portugal and Galicia.[15] Little more is known due to the scarcity of records from the Roman possession of the Iberian Peninsula. | |

| 79 CE | Gulf of Naples, Italy | Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 | Volcanic eruption | A smaller tsunami was witnessed in the Bay of Naples by Pliny the Younger during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.[16] |

| 115 CE | Caesarea, Israel | Earthquake (?) | Underwater geoarchaeological excavations on the shallow shelf (∼10 m depth) at Caesarea, Israel, documented a tsunami that struck the ancient harbor. Talmudic sources record a tsunami on 13 December 115, impacting Caesarea and Yavne. The tsunami was probably triggered by an earthquake that destroyed Antioch, and was generated somewhere on the Cyprian Arc fault system.[17] | |

| 262 CE | Southwest Anatolia (Turkey) | 262 Southwest Anatolia earthquake | Earthquake | Many cities were flooded by the sea, with the cities of Roman Asia reporting the worst tsunami damage. In many places, fissures appeared in the earth and filled with water; in others, towns were overwhelmed by the sea.[18][19][20] |

| 365 CE | Alexandria, Southern and Eastern Mediterranean | 365 Crete earthquake | Earthquake | On the morning of 21 July 365, an earthquake caused a tsunami more than 100 feet (30 m) high, devastating Alexandria and the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean, killing many thousands, and hurling ships nearly two miles inland.[21][22] This tsunami also devastated many large cities in what is now Libya and Tunisia. The anniversary of the disaster was still commemorated annually at the end of the 6th century in Alexandria as a "day of horror."[23]

Researchers at the University of Cambridge recently carbon dated corals on the coast of Crete which were lifted 10 metres and clear of the water during the earthquake, indicating the tsunami was generated by an earthquake in a steep fault in the Hellenic Trench. Scientists estimate that such an uplift is only likely to occur once in 5,000 years; however, the other segments of the fault could slip on a similar scale every 800 years or so.[24] |

| 551 CE | Lebanese Coast | 551 Beirut earthquake | Earthquake | The 9 July 551 CE earthquake was one of the largest seismic events in and around Lebanon during the Byzantine period. The earthquake was associated with a tsunami along the Lebanese coast and a local landslide near Al-Batron. A large fire in Beirut also continued for almost two months.[25] |

| 684 CE | Nankai, Japan | 684 Hakuho earthquake, Nankai earthquake | Earthquake | The first recorded tsunami in Japan, it hit on 29 November 684 on the shore of the Kii, Shikoku, and Awaji region. The earthquake, estimated at magnitude 8.4,[15] was followed by a huge tsunami, but no estimates exist for the number of deaths.[26] |

| 869 CE | Sanriku, Japan | 869 Jogan Sanriku earthquake | Earthquake | The Sanriku region was struck by a major tsunami that caused flooding extending 4 km inland from the coast. The town of Tagajō was destroyed, with an estimated 1,000 casualties. |

| 887 CE | Nankai, Japan | 887 Ninna Nankai earthquake | Earthquake | On 26 August of the Ninna era, there was a strong shock in the Kyoto region, causing great destruction. A tsunami flooded the coastal region, and some people died. The coast of Settsu Province (Osaka Prefecture) suffered especially heavily, and the tsunami was also observed on the coast of the Sea of Hyūga (Miyazaki Prefecture).[15] |

1000–1700 CE

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1293 | Kamakura, Japan | 1293 Kamakura earthquake | Earthquake | A magnitude 7.1 quake and tsunami hit Kamakura, then Japan's de facto capital, killing 23,000 after resulting fires. |

| 1303 | Eastern Mediterranean | 1303 Crete earthquake | Earthquake | A team from Southern Cross University in Lismore, New South Wales, Australia, found evidence of five tsunamis that hit Greece over the past 2000 years. "Most were small and local, but in 1303 a larger one hit Crete, Rhodes, Alexandria and Acre in Israel."[27] |

| 1361 | Nankai, Japan | 1361 Shōhei Nankai earthquake | Earthquake | On 3 August 1361, during the Shōhei era, an 8.4 quake hit Nankaidō, followed by a tsunami. A total of 660 deaths were reported. The earthquake shook Awa, Settsu, Kii, Yamato and Awaji Provinces (Tokushima, Osaka, Wakayama and Nara Prefectures and Awaji Island). A tsunami struck Awa and Tosa Provinces (Tokushima and Kōchi Prefectures), in Kii Strait and in Osaka Bay. The Hot spring of Yunomine, Kii (Tanabe, Wakayama) stopped. The port of Yuki, Awa (Minami, Tokushima) was destroyed, and more than 1,700 houses were washed away. |

| 1420 | Caldera, Chile | 1420 Caldera earthquake | Earthquake | On 1 September 1420, an enormous earthquake shook what is now Chile's Atacama Region. Landslides occurred along the coast and tsunamis affected not only Chile but also Hawaii and Japan.[28][29] |

| 1498 | Nankai, Japan | 1498 Nankai earthquake | Earthquake | On 20 September 1498, during the Meiō era, a 7.5 earthquake hit. The ports in Kii Province (Wakayama Prefecture) were damaged by a tsunami several meters high. 30–40 thousand deaths estimated.[15][30] The building around the great Buddha of Kamakura (altitude 7m) was swept away by the tsunami.[31] |

| 1531 | Lisbon, Portugal | 1531 Lisbon earthquake | Earthquake | The earthquake of 26 January was accompanied by a tsunami in the Tagus River that destroyed ships in Lisbon harbour |

| 1541 | Nueva Cadiz, Venezuela | Earthquake | In 1528, Cristóbal Guerra founded Nueva Cádiz on the island of Cubagua, the first Spanish settlement in Venezuela. Nueva Cádiz, with a population of 1000–1500, may have been destroyed in an earthquake followed by tsunami in 1541—it also could have been a major hurricane.[32] The ruins were declared a National Monument of Venezuela in 1979. | |

| 1605 | Nankai, Japan | 1605 Nankai earthquake | Earthquake | On 3 February 1605, in the Keichō era, a magnitude 8.1 quake and tsunami hit Japan. A tsunami with a maximum known height of 30 m was observed from the Bōsō Peninsula to the eastern part of Kyushu Island. The eastern part of the Bōsō Peninsula, Edo Bay (Tokyo Bay), Sagami and Tōtōmi Provinces (Kanagawa and Shizuoka Prefectures), and the southeastern coast of Tosa Province (Kōchi Prefecture) suffered particularly heavily.[15] 700 houses (41%) in Hiro, Kii (Hirogawa, Wakayama) were washed away, and 3,600 people drowned in the area of Shishikui, Awa (Kaiyō, Tokushima). Wave heights reached 5–6 meters at Kannoura, Tosa (Tōyō, Kōchi) and 8–10 m at Sakihama, Tosa (Muroto, Kōchi). 350 drowned at Kannoura and 60 at Sakihama. In total more than 5,000 drowned. |

| 1607 | Bristol Channel, Great Britain | Bristol Channel floods, 1607 | Disputed | On 30 January 1607, at least 2,000 drowned, while houses and villages were swept away and an area of ~200 square miles (520 km2) was inundated. Until the 1990s, it was undisputed that flooding was caused by a storm surge aggravated by other factors, but recent research indicates a tsunami.[33] The postulated cause is a submarine earthquake off the Irish coast. |

| 1677 | Bōsō Peninsula, Japan | 1677 Bōsō earthquake | Earthquake | On 4 November 1677, an earthquake was felt with low intensity in the area around the Bōsō Peninsula, but was followed a major tsunami, killing an estimate 569 people.[34] |

| 1693 | Sicily | 1693 Sicily earthquake | Earthquake | A large foreshock on 9 January was followed on 11 January by the most powerful earthquake in Italian history. The ensuing tsunami devastated the Ionian Sea coast and the Straits of Messina. It remains unclear whether the tsunami was directly caused by the earthquake or by a large underwater landslide triggered by the event. |

1700s

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700 | Pacific Northwest, U.S. and Canada | 1700 Cascadia earthquake | Earthquake | On 26 January 1700, the Cascadia earthquake, estimated Mw 9, ruptured the Cascadia subduction zone (C SZ) from Vancouver Island to California, and caused a massive tsunami recorded in Japan and by the oral traditions of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest. The wave caught the Japanese off-guard, not knowing its origin, and was explained in the book, The Orphan Tsunami.[35] |

| 1707 | Nankai, Japan | 1707 Hōei earthquake | Earthquake | On 28 October 1707, during the Hōei era, a magnitude 8.4 earthquake and tsunami up to 10 meters (33 feet) in height[36] struck Tosa Province (Kōchi Prefecture). More than 29,000 houses were destroyed, causing ~30,000 deaths. In Tosa, 11,170 houses were washed away, and 18,441 people drowned. About 700 drowned and 603 houses were washed away in Osaka. Hot springs at Yunomine, Kii (Tanabe, Wakayama), Sanji (?), Ryujin, Kii (Tanabe, Wakayama) Kanayana (Shirahama, Wakayama) and Dōgo, Iyo (Matsuyama, Ehime) stopped flowing.[15] |

| 1731 | Storfjorden, Norway | Storfjorden | Landslide | On 8 January 1731, a landslide into the Storfjorden opposite Stranda triggered a tsunami up to 100 metres (328 ft) in height that killed 17 people.[37] |

| 1741 | Western Oshima, Japan | Volcano | On 29 August 1741, the western side of Oshima Peninsula, Ezo (Hokkaido) was hit by a tsunami caused by eruption of the volcano on Ōshima island. The tsunami itself is thought to have resulted from a landslide, partly submarine, triggered by the eruption.[38] 1,467 people were killed on Ezo.[39] | |

| 1755 | Lisbon, Portugal | 1755 Lisbon earthquake | Earthquake | Tens of thousands of Portuguese people who survived the Great Lisbon earthquake on 1 November 1755 were killed by a tsunami 40 minutes later. Many fled to the waterfront, an area safe from fires and debris during aftershocks. These people observed the sea receding, revealing a sea floor littered with lost cargo and shipwrecks. The tsunami then struck with a maximum height of 15 metres (49 ft), traveling far inland.

The earthquake, tsunami, and fires killed 40,000 to 50,000 people.[40] Historical records of early navigators such as Vasco da Gama were lost, and among the buildings destroyed were most examples of Portugal's Manueline architecture. Europeans of the 18th century struggled to understand the disaster within religious and rational belief systems, and philosophers of the Enlightenment, notably Voltaire, wrote about the event. The philosophical concept of the sublime, as described by Immanuel Kant took inspiration from attempts to comprehend the enormity of the Lisbon quake and tsunami. The tsunami took just over 4 hours to travel over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) to Cornwall in the United Kingdom. An account by Arnold Boscowitz claimed "great loss of life." It also hit Galway, Ireland, and caused serious damage to the Spanish Arch section of the city wall. |

| 1756 | Langfjorden, Norway | Langfjorden | Landslide |

On 22 February 1756, a landslide into the Langfjorden generated three megatsunamis in the Langfjorden and the Eresfjorden with heights of 40 to 50 metres (131 to 164 ft). The waves killed 32 people and destroyed 168 buildings, 196 boats, large amounts of forest, and roads and boat landings.[41] |

| 1771 | Yaeyama Islands, Ryūkyū | 1771 Great Yaeyama Tsunami | Earthquake |

An undersea earthquake of magnitude ~7.4 occurred near Yaeyama Islands in the former Ryūkyū Kingdom (present day Okinawa, Japan) on 4 April 1771 at about 8 A.M. The earthquake is not believed to have directly caused any deaths, but a resulting tsunami killed an estimated 12,000 people[42]). Run-up estimates on Ishigaki Island range from 30 to 85.4 meters (99 to 280 feet). The tsunami was followed by malaria epidemics and crop failures. It took 148 years for the population to return to pre-tsunami levels. |

| 1781 | Pingtung, Taiwan | In April or May 1781, according to Records of Taiwan County, in Jiadong, Pingtung County, a ten-foot wave engulfed the town. Fish and shrimp thrashed wildly on the shore and nearby fishing villages were wiped out. However, no earthquake was reported.[43] A different source claims a 30-meter (99-foot) wave with also struck Tainan.[44] One possibility is a misrecording of date, corresponding with the above Great Yaeyama event. | ||

| 1783 | Calabria, Italy | 1783 Calabrian earthquakes | Earthquake | The earthquake was the second of a sequence of five shocks that struck Calabria. The citizens of Scilla spent the night following the first earthquake on the beach, where they were swept away by the tsunami, causing 1,500 deaths. The tsunami was caused by the collapse of Monte Paci into the sea, near the town. Estimated deaths from earthquake and tsunami is 32,000–50,000. |

| 1792 | Kyūshū, Japan | 1792 Unzen earthquake and tsunami | Volcanic processes | Tsunamis were the main cause of death for Japan's worst-ever volcanic disaster, an eruption of Mount Unzen, Hizen Province (Nagasaki Prefecture), Kyushu, Japan. Toward the end of 1791 a series of earthquakes on the west flank of Mount Unzen moved towards Fugen-dake, one of Mount Unzen's peaks. In February 1792, Fugen-dake erupted, initiating two-months of lava flows. Earthquakes continued, shifting nearer to the city of Shimabara. On the night of 21 May, two large earthquakes preceded a collapse of the east flank of Mount Unzen's Mayuyama dome. An avalanche swept through Shimabara and into Ariake Bay, triggering a tsunami. The tsunami struck Higo Province (Kumamoto Prefecture) across Ariake Bay before bouncing back. Out of an estimated 15,000 fatalities, ~5,000 are thought to have been killed by the landslide, ~5,000 by the tsunami in Higo Province, and ~5,000 by the tsunami returning to Shimabara. The waves reached a height of 330 ft (100 m), making this a small megatsunami. |

| 1797 | Sumatra, Indonesia | 1797 Sumatra earthquake | Earthquake | On 10 February 1797, a massive earthquake estimated to have been approximately 8.4 on the moment magnitude scale, struck Sumatra in Indonesia. Many fatalities resulted although it is not known how many. |

1800s

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806 | Goldau, Switzerland | 1806 Goldau landslide | Landslide | A landslide of 120,000,000 tonnes of rock, much of which displaced water from Lake Lauerz causing a tsunami that flooded lake side villages and resulted in the confirmed death of 457 people. |

| 1819 | Gujarat, India | 1819 Rann of Kutch earthquake | Earthquake | A local tsunami flooded the Great Rann of Kutch |

| 1833 | Sumatra, Dutch East-Indies | 1833 Sumatra earthquake | Earthquake | On 25 November 1833, an earthquake with estimated moment magnitude between 8.8–9.2, struck Sumatra in the Dutch East-Indies. The coast of Sumatra near the quake's epicentre was hardest hit by the resulting tsunami. |

| 1853–1854 | Lituya Bay, Alaska | Landslide | Sometime between August 1853 and May 1854, a very large tsunami traveled down the bay. The wave had a maximum run-up height of 120 metres (394 ft), flooding the coast of the bay up to 750 feet (229 m) inland.[45] | |

| 1854 | Nankai, Tōkai, and Kyushu, Japan | Ansei great earthquakes | Earthquake | The Ansei quake which hit the south coast of Japan, was actually a set of three earthquakes over the course of several days.

The total result was 80,000–100,000 deaths.[48] |

| 1855 | Edo, Japan | 1855 Ansei Edo earthquake | Earthquake | The following year, the 1855 Great Ansei Edo earthquake hit the Edo (Tokyo) region of Japan, killing 4,500 to 10,000 people. Popular stories of the time blamed the quakes and tsunamis on giant catfish called Namazu thrashing about. The Japanese era name was changed to bring good luck after four disastrous quakes/tsunamis in two years. |

| 1867 | Virgin Islands | Earthquake | On 18 November 1867, a large doublet earthquake occurred in the Virgin Islands archipelago. The shock probably occurred between the islands of Saint Thomas and Saint Croix. The highest runup of 7.6 m (25 ft) was observed at Frederiksted on Saint Croix, and came within minutes of the shocks.[49] | |

| 1867 | Keelung, Taiwan | Earthquake | 18 December 1867, a large quake hit Keelung, Taiwan, causing crustal deformation of the mountains and opening of fissures. The water drained out of Keelung harbor so that the sea bed was revealed, then returned in a huge wave. Boats were washed into the city center. In many locations, the ground and the mountains split open and water poured from the fissures. Hundreds of deaths resulted.[43][44] | |

| 1868 | Hawaiian Islands | 1868 Hawaii earthquake | Earthquake | On 2 April 1868, a local earthquake of estimated magnitude 7.5–8.0 rocked the southeast coast of the Big Island of Hawaii. It triggered a landslide on the slopes of Mauna Loa volcano, five miles (8 km) north of Pahala, killing 31 people. A tsunami then claimed 46 additional lives. The villages of Punaluu,k Ninole, Kawaa, Honuapo, and Keauhou Landing were severely damaged and the village of Apua was destroyed. According to one account, the tsunami "rolled in over the tops of the coconut trees, probably 60 feet high .... inland a distance of a quarter of a mile in some places, taking out to sea when it returned, houses, men, women, and almost everything movable." This was reported in the 1988 edition of Walter C. Dudley's book "Tsunami!" (ISBN 0-8248-1125-9). |

| 1868 | Arica, Peru (now part of Chile) | 1868 Arica earthquake | Earthquake | On 16 August 1868, an earthquake with a magnitude estimated at 8.5 struck the Peru–Chile Trench. A resulting tsunami struck the port of Arica, then part of Peru, killing an estimated 25,000 in Arica and 70,000 in all. Three military vessels anchored at Arica, the US warship USS Wateree and the storeship Fredonia, and the Peruvian warship America, were swept up by the tsunami.[50] |

| ca. 1874 | Lituya Bay, Alaska | Landslide | Sometime around 1874, perhaps in May 1874, a megatsunami occurred in Lituya Bay. It had a maximum run-up height of 80 feet (24 m), flooding the coast of the bay up to 2,100 feet (640 m) inland.[51] | |

| 1877 | Iquique, Chile | 1877 Iquique earthquake | Earthquake | On 9 May 1877, an earthquake with a magnitude estimated at 8.5 occurred off the coast of what is now Chile, causing a tsunami that killed about 2541 people. This event followed the destructive earthquake and tsunami at Arica by just nine years.[52] |

| 1881 | Andaman Islands, Nicobar Islands | 1881 Nicobar Islands earthquake | Earthquake | The tsunami triggered by this earthquake was recorded on all the coasts of the Bay of Bengal by tide gauges. This information has been used to estimate the rupture area and magnitude of the earthquake. |

| 1883 | Krakatoa, Sunda Strait, Netherlands East Indies | 1883 eruption of Krakatoa | Volcanic eruption | The island volcano of Krakatoa in the Dutch East-Indies (present-day Indonesia) exploded on 26–27 August 1883, blowing its underground magma chamber partly empty such that much overlying land and seabed collapsed into it. The collapse generated a series of large tsunami waves, some higher than 40 meters above sea level. Tsunami waves were observed throughout the Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, and as far away as the American West Coast, and South America. On the facing coasts of Java and Sumatra the sea flood went many miles inland and caused such loss of life[53] that one area was never resettled, reverting to jungle and is now the Ujung Kulon nature reserve. |

| 1888 | Ritter Island, Netherlands East Indies | Ritter Island | Volcanic eruption | On 13 March 1888, a significant portion of Ritter Island collapsed into the sea, generating tsunamis of up to 12 to 15 metres (39 to 49 ft) in height that struck nearby islands and traveled as far south as New Guinea, where they were 8 metres (26 ft) high. The waves killed around 3,000 people.[54][55] [56][57][58] |

| 1896 | Sanriku, Japan | 1896 Sanriku earthquake | Earthquake | On 15 June 1896, at around 19:36 local time, a large undersea earthquake off the Sanriku coast of northeastern Honshu, Japan, triggered tsunami waves which struck the coast about half an hour later. Although the earthquake itself is not thought to have resulted in fatalities, the waves, which reached a height of 100 feet (30 m), killed approximately 27,000 people. In 2005, the same general area was hit by the 2005 Sanriku Japan earthquake, but with no major tsunami. |

1900–1950

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | Loenvatnet, Norway | Rockfall | On 15 January 1905, a rockfall hit the lake Loenvatnet in Sogn og Fjordane, creating a 40 m (130 ft) flood wave that destroyed the villages of Ytre Nesdal and Bødal, killing 61 people.[59] The slide, which started 500 metres up the mountainside of Mount Ramnefjell, carried an approximate mass of 870,000 metric tons when it entered the lake.[60] | |

| 1905 | Disenchantment Bay, Alaska | Glacier collapse | On 4 July, a tsunami in Disenchantment Bay in Alaska broke tree branches 110 feet (34 m) above ground level 0.5 miles (0.8 km) away from its origin, killed vegetation to a height of 65 feet (20 m) at a distance of 3 miles (5 km) away, and reached heights of from 50 to 115 feet (15 to 35 m) at various locations on the coast of Haenke Island. At a distance of 15 miles (24 km), observers at Russell Fjord reported a series of large waves that caused the water level to rise and fall 15 to 20 feet (5 to 6 m) for a half-hour.[61] | |

| 1906 | Tumaco-Esmeraldas, Colombia-Ecuador | 1906 Ecuador–Colombia earthquake | Earthquake | The earthquake triggered a tsunami that killed 500 people in Tumaco and Esmeraldas and struck Colombia, Ecuador, California, Hawaii, and Japan. Waves were 5 meters high. |

| 1907 | Simeulue, Nias off Sumatra | 1907 Sumatra earthquake | Earthquake | A tsunami earthquake that triggered a transoceanic tsunami, which caused 2,188 deaths on Simeulue and Nias[62] |

| 1908 | Messina, Italy | 1908 Messina earthquake | Underwater landslide triggered by an earthquake |  The aftermath of the tsunami that struck Messina in 1908 |

| 1918 | Puerto Rico | 1918 San Fermín earthquake | Earthquake/submarine landslide | A large tsunami (that may have been associated with a submarine landslide) affected northwest Puerto Rico.[64] |

| 1923 | Kantō, Japan | 1923 Great Kantō earthquake | Earthquake | The Great Kantō earthquake, which occurred in eastern Japan on 1 September 1923, and devastated Tokyo, Yokohama, and the surrounding areas, caused tsunamis which struck the Shōnan coast, Bōsō Peninsula, Izu Islands and the east coast of Izu Peninsula, within minutes in some cases. In Atami, waves reaching 12 meters were recorded. Examples of tsunami damage include about 100 people killed along Yuigahama beach in Kamakura and an estimated 50 people on the Enoshima causeway. However, tsunamis only accounted for a small proportion of the final death toll of over 100,000, most of whom were killed in fire. |

| 1929 | Newfoundland | 1929 Grand Banks earthquake | Earthquake | On 18 November 1929, an earthquake of magnitude 7.2 occurred beneath the Laurentian Slope on the Grand Banks. The quake was felt throughout the Atlantic Provinces of Canada and as far away as Ottawa and Claymont, Delaware. The resulting tsunami measured over 7 meters in height and took about 21/2 hours to reach the Burin Peninsula on the south coast of Newfoundland, where 28 people lost their lives in various communities. It also snapped telegraph cables laid under the Atlantic.[65] |

| 1932 | Mexico | 1932 Jalisco earthquakes | Earthquake | Three very large-to-great shocks off the coast of Jalisco in June 1932 each generated tsunamis. The last and smallest event in the series occurred updip relative to the mainshock and generated the largest tsunami.[66] |

| 1933 | Sanriku, Japan | 1933 Sanriku earthquake | Earthquake | On 3 March 1933, the Sanriku coast of northeastern Honshu, Japan, which suffered a devastating tsunami in 1896 (see above), was again struck by tsunami waves resulting from an offshore magnitude 8.1 earthquake. The quake destroyed ~5,000 homes and killed 3,068 people, the vast majority as a result of tsunami waves. Especially hard hit was the coastal village of Tarō (now part of Miyako city) in Iwate Prefecture, which lost 42% of its total population and 98% of its buildings. Tarō is now protected by a tsunami wall, currently 10 meters in height and over 2 kilometers long.[67] |

| 1934 | Tafjorden, Norway | Tafjorden | Rockslide | On 7 April 1934, a rockslide of about 2,000,000 cubic metres (2,600,000 cu yd) of rock fell off the mountain Langhamaren from a height of about 700 metres (2,300 ft). The rock landed in the Tafjorden which created a local tsunami which killed 40 people[68] living on the shore of the fjord. The waves reached a height of 62 metres (203 ft) near the landslide, about 7 metres (23 ft) at Sylte, and about 16 metres (52 ft) at Tafjord. It was one of the worst natural disasters in Norway in the 20th century.[69] |

| 1936 | Loenvatnet, Norway | Rockfall | On 13 September, approximately one million cubic metres of mountainside dislodged from the Mt. Ramnefjell at a height of 800 metres[60] and landed in lake Loenvatnet in Sogn og Fjordane, creating a 70 m (230 ft) flood wave that destroyed several farms, killing 74 people. The second such incident in 31 years, the disaster caused the permanent depopulation of the area.[70] | |

| 1936 | Lituya Bay, Alaska | Unknown | On 27 October, a megatsunami occurred in Lituya Bay in Alaska with a maximum run-up height of 490 feet (149 m) in Crillon Inlet at the head of the bay. The four eyewitnesses to the wave in Lituya Bay itself all survived and described it as between 100 and 250 feet (30 and 76 m) high as it traveled down the bay. The maximum inundation distance was 2,000 feet (610 m) inland along the north shore of the bay. The cause of the megatsunami remains unclear, but may have been a submarine landslide.[71] | |

| 1944 | Tōnankai, Japan | 1944 Tōnankai earthquake | Earthquake | A magnitude 8.0 earthquake on 7 December 1944, about 20 km off the Shima Peninsula in Japan, which struck the Pacific coast of central Japan, mainly Mie, Aichi, and Shizuoka Prefectures. News of the event was downplayed by the authorities in order to protect wartime morale, and as a result the full extent of the damage is not known, but the quake is estimated to have killed 1223 people, the tsunami being the leading cause of the fatalities. |

| 1945 | Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean | 1945 Balochistan earthquake | Earthquake | The earthquake with moment magnitude of 8.1 and a maximum perceived intensity of X (Extreme) on the Mercalli intensity scale, occurred in British India at 5:26 PST on 28 November 1945. It resulted from a fault rupture near the Makran Trench. The resulting tsunami caused damage along the Makran coastal region affecting Pakistan, Iran, Oman and India.[72][73] |

| 1946 | Nankai, Japan | 1946 Nankai earthquake | Earthquake | The Nankai earthquake on 21 December 1946 had a magnitude of 8.4 and occurred at 04:19 (local time) to the southwest of Japan in the Nankai Trough. This event was one of the Nankai megathrust earthquakes, periodic earthquakes observed off the southern coast of Kii Peninsula and Shikoku, Japan every 100 to 150 years. The subsequent tsunami washed away 1451 houses and caused 1500 deaths in Japan, and was observed on tide gauges in California, Hawaii, and Peru.[15] Particularly hard hit were the coastal towns of Kushimoto and Kainan on the Kii Peninsula. The quake led to more than 1400 deaths, tsunami being the leading cause. |

| 1946 | Aleutian Islands | 1946 Aleutian Islands earthquake | Earthquake |  Residents running from an approaching tsunami in Hilo, Hawaii On 1 April 1946, the Aleutian Islands tsunami killed 159 people on Hawaii and five in Alaska (the lighthouse keepers at the Scotch Cap Light in the Aleutians). The wave reached Kauai, Hawaii 4.5 hours after the quake, and Hilo, Hawaii 4.9 hours later. The residents of these islands were caught completely off-guard by the onset of the tsunami due to the inability to transmit any warnings from the destroyed posts at Scotch Cap Light on Unimak Island in Alaska. The tsunami is known as the April Fools Day Tsunami in Hawaii because it happened on 1 April and many people thought it to be an April Fool's Day prank. It resulted in the creation of a tsunami warning system known as the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), established in 1949 for Oceania countries. |

1950–2000

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Severo-Kurilsk, Kuril Islands, USSR | 1952 Severo-Kurilsk earthquake | Earthquake | 5 November 1952 tsunami, triggered by a magnitude 9.0 earthquake, killed 2,336 on the Kuril Islands, USSR. |

| 1956 | Amorgos, Greece | Earthquake | Fifty-three deaths occurred during the largest 20th-century earthquake in Greece. Santorini was damaged, and a localised tsunami affected the Cyclades and Dodecanese island groups. Maximum runup of 30 m (98 ft)) was observed on the southern coast of Amorgos.[74] | |

| 1958 | Lituya Bay, Alaska, U.S. | 1958 Lituya Bay, Alaska earthquake and megatsunami | Earthquake-triggered landslide | The night of 9 July 1958 an earthquake on the Fairweather Fault in Alaska loosened ~40 million cubic yards (30.6 million cubic meters) of rock 3000 feet (914 meters) above the northeastern shore of Lituya Bay. The impact in the waters of Gilbert Inlet generated a local tsunami that crashed against the southwest shoreline and swept over the spur separating Gilbert Inlet from the main Lituya Bay. The wave continued down Lituya Bay, over La Chaussee Spit and into the Gulf of Alaska. The force of the wave removed all trees and vegetation from as high as 1720 feet (524 meters) above sea level. This is the highest wave ever recorded. The scale of this wave was so much greater than ordinary tsunamis, it eventually led to the new category of megatsunamis. |

| 1960 | Valdivia, Chile, and Pacific Ocean | 1960 Valdivia earthquake or Great Chilean earthquake | Earthquake | The magnitude-9.5 earthquake of 22 May 1960, the largest earthquake ever recorded, generated one of the most destructive tsunamis of the 20th century. The tsunami spread across the Pacific Ocean, with waves measuring up to 25 meters (82 feet) high in places. The first tsunami wave struck at Hilo, Hawaii, approximately 14.8 hrs after it originated. The highest wave at Hilo Bay was measured at ~10.7 m (35 ft). 61 lives were lost, allegedly due to people's failure to heed warning sirens. Almost 22 hours after the quake, waves up to 3 m above high tide hit the Sanriku coast of Japan, killing 142 people. Up to 6,000 people died in total worldwide due to the earthquake and tsunami.[75] |

| 1963 | Vajont Dam, Monte Toc, Italy | Vajont Dam | Landslide |  The Vajont Dam as seen from Longarone on 25 September 2012, showing the top 60–70 metres. The 200–250-metre (656–820-foot) megatsunami would have obscured virtually all of the sky in this picture. The Vajont Dam was completed in 1961 under Monte Toc, 100 km north of Venice, Italy. At 262 metres (860 feet), it was one of the highest dams in the world. On 9 October 1963 a landslide of about 260 million cubic meters of forest, earth, and rock, fell into the reservoir at up to 110 km per hour (68 mph). The resulting displacement of water caused 50 million cubic metres of water to overtop the dam in a 250-metre (820-foot) high megatsunami wave. The flooding destroyed the villages of Longarone, Pirago, Rivalta, Villanova and Faè, killing 1,450 people. Nearly 2,000 people perished in total. |

| 1964 | Niigata, Japan | 1964 Niigata earthquake | Earthquake | 28 people died, and entire apartment buildings were destroyed by liquefaction of the ground. The subsequent tsunami destroyed the port of Niigata. |

| 1964 | Alaska, U.S. and Pacific Ocean | 1964 Alaska earthquake | Earthquake | After the magnitude 9.2 Good Friday earthquake of 27 March 1964, tsunamis struck Alaska, British Columbia, California, and coastal Pacific Northwest towns, killing 121 people. The waves were up to 100 feet (30 m) tall, and killed 11 people as far away as Crescent City, California. |

| 1965 | Shemya Island, Alaska | 1965 Rat Islands earthquake | Earthquake | The 4 February 1965, Rat Islands earthquake generated a 10.7-metre (35 ft) tsunami on Shemya Island.[76] |

| 1969 | Portugal, Morocco | 1969 Portugal earthquake | Earthquake | A large undersea earthquake off the coast of Portugal generated a tsunami that affected both Portugal and Morocco.[77] |

| 1976 | Moro Gulf, Mindanao, Philippines | 1976 Moro Gulf earthquake | Earthquake | On 16 August 1976 at 12:11 A.M., magnitude 7.9 earthquake hit the island of Mindanao, Philippines. The resultant tsunami devastated more than 700 km of coastline bordering Moro Gulf in the North Celebes Sea. Estimated casualties included 5,000 dead, 2,200 missing, 9,500 injured, and 93,500 people left homeless. Affected cities include Cotabato, Pagadian, and Zamboanga, and the provinces of Basilan, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Sultan Kudarat, Sulu, and Zamboanga del Sur. |

| 1979 | Tumaco, Colombia | 1979 Tumaco earthquake | Earthquake | A magnitude 8.1 earthquake occurred on 12 December 1979 at 7:59:4.3 UTC along the Pacific coast of Colombia and Ecuador. The earthquake and resulting tsunami destroyed at least six fishing villages and killed hundreds of people in the Colombian Department of Nariño. The earthquake was felt in Bogotá, Cali, Popayán, Buenaventura, Guayaquil, Esmeraldas, and Quito. The tsunami caused huge destruction in the city of Tumaco, as well as in the towns of El Charco, San Juan, Mosquera, and Salahonda on the Pacific coast of Colombia. Casualties included 259 dead, 798 wounded and 95 missing or presumed dead. |

| 1980 | Spirit Lake, Washington, U.S. | Spirit Lake (Washington), 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, Mount St. Helens | Volcanic eruption | On 18 May 1980, in the course of a major eruption of Mount St. Helens, the upper 460 m (1400 ft) of the mountain failed, causing a major landslide. One lobe of the landslide surged onto the nearby Spirit Lake, creating a megatsunami 260 meters (853 feet) high.[78] |

| 1983 | Sea of Japan | 1983 Sea of Japan earthquake | Earthquake | On 26 May 1983 at 11:59:57 local time, a magnitude-7.7 earthquake occurred in the Sea of Japan, about 100 km west of the coast of Noshiro in Akita Prefecture. Out of 107 fatalities, all but four were killed by the resulting tsunami, which struck communities along the coast, especially Aomori and Akita Prefectures and the Noto Peninsula. Footage of the tsunami hitting the fishing harbor of Wajima on Noto Peninsula was broadcast on TV. Waves exceeded 10 meters in some areas. Three of the fatalities were along the east coast of South Korea (whether North Korea was affected is not known). The tsunami also hit Okushiri Island. |

| 1992 | Nicaragua | 1992 Nicaragua earthquake | Earthquake | A 7.2+ quake hit offshore in Nicaragua, sending a devastating tsunami into the Rivas department coast, killing some 116 people. The wave magnitude, 9.9 meters high, was unusually large given the size of the earthquake. |

| 1993 | Okushiri, Hokkaido, Japan | 1993 Hokkaido earthquake | Earthquake | A devastating tsunami wave struck Hokkaido in Japan as a result of a magnitude 7.8 offshore earthquake 80 miles (130 km) on 12 July 1993. Within minutes, the Japan Meteorological Agency issued a tsunami warning that was broadcast on NHK in English and Japanese (archived at NHK library). However, at Okushiri, a small island near the epicenter, some waves reaching 30 meters struck within two to five minutes of the quake. Despite being surrounded by tsunami barriers, Aonae, a village on a low-lying peninsula, was struck over the following hour by 13 waves over two meters high arriving from multiple directions, including waves that bounced back off Hokkaido. Of 250 people killed as a result of the quake, 197 were victims of the tsunami that hit Okushiri; the waves also caused deaths on Hokkaido. While many residents, remembering the 1983 tsunami (see above), survived by evacuating on foot, many others underestimated how soon the waves would arrive (the 1983 tsunami took 17 minutes to hit Okushiri) and were killed as they attempted to evacuate by car. The highest wave of the tsunami was 31 meters (102 ft) high. |

| 1994 | Java earthquake | 1994 Java earthquake | Earthquake | Two hundred and fifty killed as a M7.8 earthquake and tsunami affected east Java and Bali on 3 June 1994. |

| 1998 | Papua New Guinea | 1998 Papua New Guinea earthquake | Earthquake | On 17 July 1998, a Papua New Guinea tsunami killed approximately 2,200 people.[79] A 7.1-magnitude earthquake 24 km offshore was followed within 11 minutes by a tsunami about 15 metres tall. The tsunami was generated by an undersea landslide, which was triggered by the earthquake. The villages of Arop and Warapu were destroyed. |

| 1999 | Sea of Marmara | 1999 İzmit earthquake | Earthquake | The earthquake triggered a tsunami in the Sea of Marmara, with a maximum water height of 2.52 m. 150 people were killed when the town of Degirmendere was flooded and a further five were swept into the sea at Ulaşlı.[80][81] |

2000s/2010s

| Date | Location | Main Article | Primary Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Indian Ocean | 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami | Earthquake |  The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake; Tsunami striking Ao Nang, Thailand  Animation of the tsunami caused by the earthquake showing how the tsunami radiated from the entire length of the 1,600 km (990 mi) rupture The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake (moment magnitude 9.1–9.3)[15] triggered a series of tsunamis on 26 December 2004, killing approximately 227,898 people (167,540 in Indonesia alone), making it the deadliest tsunami and one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. The earthquake was the third largest earthquake in recorded history. The initial surge was measured at a height of approximately 33 meters (108 ft), making it the largest earthquake-generated tsunami in recorded history. The tsunami killed people from the immediate vicinity of the quake in Indonesia, Thailand, and the north-west coast of Malaysia, to thousands of kilometres away in Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and as far away as Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania. This trans-Indian Ocean tsunami is an example of a teletsunami, which travels vast distances across the open ocean, and an ocean-wide tsunami. It became known as the "Boxing Day Tsunami" because it struck on Boxing Day (26 December). Unlike in the Pacific Ocean, there was no organized alert service covering the Indian Ocean. This was in part due to the absence of major tsunami events since 1883 (the Krakatoa eruption, see above). In light of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, UNESCO and other world bodies have called for an international tsunami monitoring system. |

| 2006 | South of Java Island | 2006 Pangandaran earthquake and tsunami | Earthquake | A 7.7 magnitude earthquake rocked the Indian Ocean seabed on 17 July 2006, 200 km south of Pangandaran, a beach famous to surfers for its perfect waves. This earthquake triggered tsunamis with heights that varied from 2 meters at Cilacap to 6 meters at Cimerak beach, where it swept away and flattened buildings as far as 400 metres away from the coastline. More than 800 people were reported missing or dead. |

| 2006 | Kuril Islands | 2006 Kuril Islands earthquake | Earthquake | On 15 November 2006, a magnitude 8.3 earthquake occurred off the coast near the Kuril Islands. In spite of the quake's large 8.3 magnitude, a relatively small tsunami was generated. This tsunami was recorded or observed in Japan and at distant locations throughout the Pacific. |

| 2007 | Solomon Islands | 2007 Solomon Islands earthquake | Earthquake | On 2 April 2007, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake struck about 40 km (25 mi) south of Ghizo Island in the western Solomon Islands at 7:39 a.m., resulting in a tsunami that was up to 12 m (36 feet) high. The wave, which struck the coast of Solomon Islands (mainly Choiseul, Ghizo Island, Ranongga, and Simbo), triggered tsunami warnings and watches extending from Japan to New Zealand to Hawaii and eastern Australia. The tsunami killed 52 people and dozens were injured when waves inundated towns. A state of national emergency was declared for the Solomon Islands. On the island of Choiseul, a wall of water reported to be 9.1 m (30 feet) high swept almost 400 meters inland. The largest waves hit the northern tip of Simbo Island, where two villages, Tapurai and Riquru, were completely destroyed by a 12 m wave, killing 10 people. Officials estimate that the tsunami displaced more than 5000 residents throughout the archipelago. |

| 2007 | Chile | 2007 Aysén Fjord earthquake | Earthquake and landslide | On 21 April 2007, a magnitude 6.2 earthquake occurred in the Aysén Fjord. On the mountains around the fjord, the earthquake caused landslides that in turn created waves as high as six meters, which severely damaged some salmon aquaculture installations. The potable water systems of the cities of Puerto Chacabuco and Puerto Aisén were broken, forcing firefighters and the army to supply water. The electricity network of Puerto Chacabuco was also cut off. Ten people were reported dead or missing. |

| 2007 | British Columbia | Landslide | On 4 December 2007, a landslide entered Chehalis Lake in British Columbia, generating a large lake tsunami that destroyed campgrounds and vegetation many meters above the shoreline.[82] | |

| 2009 | Samoa | 2009 Samoa earthquake and tsunami | Earthquake | A submarine earthquake took place in the Samoan Islands region at 06:48:11 local time on 29 September 2009. This magnitude 8.1 quake on the outer rise of the Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone was the largest earthquake of 2009.

The subsequent tsunami caused substantial damage and loss of life in Samoa, American Samoa, and Tonga. The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center recorded a 76 mm (3.0 in) rise in sea levels near the epicenter, and New Zealand scientists noted waves as high as 14 m (46 ft) on the Samoan coast. More than 189 people were killed, especially children, mostly in Samoa. Large waves with no major damage were reported on Fiji, the northern coast of New Zealand and Rarotonga in the Cook Islands. People on low-lying atolls of Tokelau moved to higher ground as a precaution. |

| 2010 | Chile | 2010 Chile earthquake | Earthquake |  Destruction provoked by the 2010 Chile earthquake and tsunami, in Pichilemu, O'Higgins Region, Chile On 27 February 2010, an 8.8 earthquake offshore of Chile caused a tsunami which caused serious damage and loss of life, it also caused minor effects in other Pacific nations. |

| 2010 | Sumatra | 2010 Mentawai earthquake and tsunami | Earthquake | On 25 October 2010, a 7.7 earthquake struck near South Pagai Island in Indonesia triggering a localized tsunami that killed at least 408 people. |

| 2011 | New Zealand | 2011 Christchurch earthquake | Earthquake-triggered ice fall | On 22 February 2011, a 6.3 magnitude earthquake hit the Canterbury region of the South Island, New Zealand. Some 200 kilometres (120 mi) away from the earthquake's epicenter, around 30 million tonnes of ice tumbled off the Tasman Glacier into Tasman Lake, producing a series of 3.5 m (11 ft) high tsunami waves, which hit tourist boats in the lake.[83][84] |

| 2011 | Pacific coast of Japan | 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami | Earthquake |

On 11 March 2011, off the Pacific coast of Japan, a 9.0-magnitude earthquake produced a tsunami 33 feet (10 m) high along Japan's northeastern coast. The wave caused widespread devastation, with an official count of 18,550 people confirmed to be killed/missing.[85] The highest tsunami which was recorded at Miyako, Iwate reached a total height of 40.5 metres (133 ft).[86] In addition the tsunami precipitated multiple hydrogen explosions and nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant. Tsunami warnings were issued to the entire Pacific Rim.[87][88] |

| 2013 | Solomon Islands | 2013 Solomon Islands earthquake | Earthquake | On 6 February 2013, an earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Moment Magnitude scale struck the island nation of Solomon Islands. This earthquake created tsunami waves up to around 1 meter high. The tsunami also affected some other islands like New Caledonia and Vanuatu. |

| 2014 | Iceland | Askja | Landslide | At 11:24 PM on 21 July 2014, in a period experiencing an earthquake swarm related to the upcoming eruption of Bárðarbunga, an 800m-wide section gave way on the slopes of the Icelandic volcano Askja. Beginning at 350m over water height, it caused a tsunami 20–30 meters high across the caldera, and potentially larger at localized points of impact. Thanks to the late hour, no tourists were present; however, search and rescue observed a steam cloud rising from the volcano, apparently geothermal steam released by the landslide. Whether geothermal activity played a role in the landslide is uncertain. A total of 30–50 million cubic meters was involved in the landslide, raising the caldera's water level by 1–2 meters.[89] |

| 2015 | Chile | 2015 Chile earthquake | Earthquake | On Wednesday, 16 September 2015, a major earthquake measuring 8.3 on the Moment Magnitude scale struck the west coast of Chile, causing a tsunami up to 16 feet (4.88 meters) high along the Chilean coast. |

| 2015 | Taan Fiord, Alaska, U.S. | Icy Bay (Alaska) | Landslide | On Saturday, 17 October 2015, a major landslide occurred at the head of Taan Fiord, a finger of Icy Bay. It triggered a megatsunami with an initial height of 100 metres (328 ft) and a run-up on the opposite shore of the fjord of 193 metres (633 ft). As the wave traveled down Taan Fiord toward Icy Bay, run-ups along the shore of the fjord ranged from 20 metres (66 ft) to over 100 metres (328 ft). |

| 2016 | New Zealand | 2016 Kaikoura earthquake | Earthquake | On 14 November 2016, a big earthquake struck the South Island of New Zealand measuring 7.5 to 7.8 magnitude. A 2.5-metre tsunami hit Kaikoura and other small waves less than one metre hit various shores in New Zealand. |

| 2017 | Greenland | Landslide | On 17 June 2017, a landslide measuring 300 m × 1,100 m (980 ft × 3,610 ft) fell about 1 km (3,300 ft) into the Karrat fjord in the Uummannaq area in Western Greenland. The resultant tsunami hit the settlement Nuugaatsiaq killing four people, injuring nine and washing eleven buildings into the water.[90][91] In the beginning the tsunami had a height of 90 m (300 ft), but it was significantly lower once it hit the settlement.[91] Initially it was unclear if the landslide was caused by a small earthquake (magnitude 4),[90] but later it was confirmed that the landslide had caused the tremors.[91] | |

| 2018 | Sulawesi | 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami | Earthquake-triggered underwater landslide | On 28 September 2018, a localised tsunami struck Palu, sweeping shore-lying houses and buildings on its way; the earthquake, tsunami and soil liquefaction killed at least 1,234 and injured over 600.[92] The Indonesian Agency for Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics (BMKG) confirmed that a tsunami occurred, with a height of between 1.5 to 2 metres (4.9 to 6.6 ft), striking the settlements of Palu, Donggala and Mamuju.[93] |

| 2018 | Java and Sumatra | 2018 Sunda Strait tsunami | Volcanic-eruption-triggered landslide | At 21:03 local time (14:03 UTC), Anak Krakatau erupted and damaged local seismographic equipment though a nearby seismographic station detected continuous tremors.[94] BMKG detected a tsunami event around 21:27 local time (14:27 UTC) at the western coast of Banten, but the agency had not detected any preceding tectonic events.[95] On 23 December it was confirmed via satellite data and helicopter footage that the southwest sector of the Anak Krakatau had collapsed which triggered the tsunami and the main conduit is now erupting from underwater producing Surtseyan style activity.[96] The Indonesian National Board for Disaster Management initially reported 20 deaths and 165 injuries.[97] By the following day, the figure had been revised to 43 deaths, 584 injured, and 2 missing. Of the 43 recorded deaths, 33 were killed in Pandeglang, 7 in South Lampung, and 3 in Serang, with most of the injuries recorded (491) also occurring in Pandeglang. The areas of Pandeglang struck by the wave included beaches which are popular tourist destinations.[94][98] By 29 December, the death toll had risen to 426, while the injured numbered 7,202 and the missing 24.[99] |

Highest or tallest

- The tsunami with the highest runup was the 1958 Lituya Bay megatsunami, which had a record height of 524 m (1,719 ft).

- The only other recent megatsunamis are the 1963 Vajont Dam megatsunami, which had an initial height of 250 m (820 ft), the 1980 Spirit Lake megatsunami, which measured 260 m (850 ft) tall, and the 2015 megatsunami in Taan Fiord, a finger of Icy Bay in Alaska, which had an estimated initial height of 100 metres (328 ft) and a run-up of 193 metres (633 ft).

- A tsunami caused by a landslide during the 1964 Alaska earthquake reached a height of 70 m (230 ft), making it one of the largest tsunamis in recorded history.[100]

Deadliest

The deadliest tsunami in recorded history was the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which killed almost 230,000 people in fourteen countries including Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Somalia, Myanmar, Maldives, Malaysia, Tanzania, Seychelles, Bangladesh, South Africa, Yemen and Kenya (listed in order of confirmed death numbers).[101]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Smid, T. C.: "'Tsunamis' in Greek Literature", Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 17, No. 1 (April 1970), pp. 100–04 (102f.)

- Thucydides: "A History of the Peloponnesian War", 3.89.1–5 Archived 5 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Hawaiian landslides have been catastrophic". mbari.org. Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. 22 October 2015.

- Culliney, John L. (2006) Islands in a Far Sea: The Fate of Nature in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 17.

- "Kalaupapa Settlement Boundary Study. Along North Shore to Halawa Valley, Molokai" (PDF). National Park Service. 2001. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bondevik, Stein; Dawson, Sue; Dawson, Alastair; Lohne, Øystein (5 August 2003). "Record-breaking Height for 8000-Year-Old Tsunami in the North Atlantic" (PDF). Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 84 (31): 289, 293. Bibcode:2003EOSTr..84..289B. doi:10.1029/2003EO310001. hdl:1956/729. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2011.

- Bondevik, S; Lovholt, F; Harbitz, C; Stormo, S; Skjerdal, G (2006). "The Storegga Slide Tsunami – Deposits, Run-up Heights and Radiocarbon Dating of the 8000-Year-Old Tsunami in the North Atlantic". American Geophysical Union meeting.

- Bondevik, S; Stormo, SK; Skjerdal, G (2012). Green mosses date the Storegga tsunami to the chilliest decades of the 8.2 ka cold event. Quaternary Science Reviews. 45. pp. 1–6. Bibcode:2012QSRv...45....1B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.04.020.

- Cain, Genevieve; Goff, James; McFadgen, Bruce (1 June 2019). "Prehistoric Coastal Mass Burials: Did Death Come in Waves?". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 26 (2): 714–754. doi:10.1007/s10816-018-9386-y. ISSN 1573-7764.

- Herodotus: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Hdt.+8.129.1 Archived 8 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine "The Histories", 8.129

- Antonopoulos, John (1992). "The Tsunami of 426 BC in the Maliakos Gulf, Eastern Greece". Natural Hazards. 5: 83–93. doi:10.1007/BF00127141.

- Smid, T. C.: "'Tsunamis' in Greek Literature", Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 17, No. 1 (Apr. 1970), pp. 100–04 (103f.)

- Paul Kronfield. "The Lost Cities of Ancient Helike: Principal Ancient Sources". Helike.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- NOAA National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC) (20 September 2005). "NOAA/WDS Global Historical Tsunami Database". Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Cf. tsunami-ID 01, in: Tinti S., Maramai A., Graziani L. (2007). The Italian Tsunami Catalogue (ITC) Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Version 2 (Windows database software).

- Reinhardt, E. G.; Goodman, B. N.; Boyce, J. I.; Lopez, G.; van Hengstum, P.; Rink, W. J.; Mart, Y.; Raban, A. (2006). "The tsunami of 13 December A.D. 115 and the destruction of Herod the Great's harbor at Caesarea Maritima, Israel". Geology. 34 (12): 1061–64. Bibcode:2006Geo....34.1061R. doi:10.1130/G22780A.1.

- Altınok, Y.; Alpar, B.; Özer, N.; Aykurt, H. (2011). "Revision of the tsunami catalogue affecting Turkish coasts and surrounding regions". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 11 (2): 273–291. Bibcode:2011NHESS..11..273A. doi:10.5194/nhess-11-273-2011.

- "Turkey: S Coasts; Libya: Comments for the Earthquake Event". Significant Earthquake Database. National Geophysical Data Center. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- "South Coasts of Asia Minor: Comments for the Tsunami Event". Significant Tsunami Database. National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Kelly, Gavin: "Ammianus and the Great Tsunami", The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 94 (2004), pp. 141–67 (141)

- Stanley, Jean-Daniel & Jorstad, Thomas F. (2005): "The 365 A.D. Tsunami Destruction of Alexandria, Egypt: Erosion, Deformation of Strata and Introduction of Allochthonous Material Archived 6 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine"

- Stiros, S. C. (2001), "The AD 365 Crete earthquake and possible seismic clustering during the fourth to sixth centuries AD in the Eastern Mediterranean: a review of historical and archaeological data", Journal of Structural Geology, 23 (2–3): 545–62, Bibcode:2001JSG....23..545S, doi:10.1016/s0191-8141(00)00118-8

- "Fault found for Mediterranean 'day of horror'." New Scientist magazine, 15 March 2008, p. 16.

- Darawcheh, R.; Sbeinati R., Margottini C., Paolini S. (2000). "The 9 July 551 earthquake, Eastern Mediterranean Region". Earthquake Engineering. 4 (4): 403–14. doi:10.1080/13632460009350377.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Archived 4 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Scheffers, Anja (2008). "Late Holocene tsunami traces on the western and southern coastlines of the Peloponnesus (Greece)". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 269 (1–2): 271–279. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.02.021.. In: "Fault found for Mediterranean 'day of horror'." New Scientist magazine, 15 March 2008, p. 16.

- Guzmán, L. (14 February 2019). "Encuentran registros de megaterremoto ocurrido hace seis siglos en el norte de Chile". El Mercurio (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Manuel Abad, Tatiana Izquierdo, Miguel Cáceres, Enrique Bernárdez and Joaquín Rodríguez‐Vidal (2018). Coastal boulder deposit as evidence of an ocean‐wide prehistoric tsunami originated on the Atacama Desert coast (northern Chile). Sedimentology. Publication: December, 13th, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12570

- Kamio, Kenji, and Willson, H. An English Guide to Kamakura's Temples and Shrines, pp. 143–44.

- Ishabashi, K. (1981). "Specification of a soon-to-occur seismic faulting in the Tokai District, central Japan, based on seismotectoncs". In Simpson D.W. & Pichards P.G. (ed.). Earthquake prediction: an international review. Maurice Ewing Series. 4. American Geophysical Union. pp. 323–24. ISBN 978-0-87590-403-0.

- Vila, P. (1948). "La destrucción de Nueva Cádiz ¿terremoto o huracán?". Boletín de la Academia National de la Historia. 31: 213–19.

- Bryant, Edward; Haslett, Simon (2002). "Was the AD 1607 Coastal Flooding Event in the Severn Estuary and Bristol Channel (UK) Due to a Tsunami?". Archaeology in the Severn Estuary (13): 163–67. ISSN 1354-7089. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- Yanagisawa, H.; Goto, K.; Sugawara, D.; Kanamaru, K.; Iwamoto, N.; Takamori, Y. (2016). "Tsunami earthquake can occur elsewhere along the Japan Trench—Historical and geological evidence for the 1677 earthquake and tsunami". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 121 (5): 3504–3516. Bibcode:2016JGRB..121.3504Y. doi:10.1002/2015JB012617.

- Atwater, B. F.; Musumi-Rokkaku, S.; Satake, K.; Yoshinobu, T.; Kazue, U.; Yamaguchi, D. K. (2005). The Orphan Tsunami of 1700—Japanese Clues to a Parent Earthquake in North America. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1707. United States Geological Survey–University of Washington Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0295985350. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Hatori, T. (1981). "Field investigations of the Nankaido Tsunamis in 1707 and 1854 along the South-west coast of Shikoku" (PDF). Bulletin Earthquake Research Institute (in Japanese). 56: 547–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Hoel, Christer, "The Skafjell Rock Avalanche in 1731," fjords.com Retrieved 23 June 2020

- Satake, K. (2007). "Volcanic origin of the 1741 Oshima-Oshima tsunami in the Japan Sea" (PDF). Earth Planets Space. 59 (5): 381–90. Bibcode:2007EP&S...59..381S. doi:10.1186/bf03352698. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- NGDC. "Comments for the Tsunami Event". Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- "The Opportunity of a Disaster: The Economic Impact of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake. Discussion Paper 06/03, Centre for Historical Economics and Related Research at York, York University, 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Hoel, Christer, "The Tjelle Rock Avalanche in 1756," fjords.com Retrieved 22 June 2020

- "沖縄県". .pref.okinawa.jp. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- 交通部中央氣象局 (5 March 2008). "中央氣象局-地震測報地理資訊系統首頁". 通部中央氣象局中文. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "Taiwan has a scattered history of tsunamis – Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. 29 December 2004. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Lander, pp. 39–41.

- Sugawara, D.; Minoura K.; Imamura F.; Takahashi T.; Shuto N. (2005). "A huge sand dome, ca. 700,000 m3 in volume, formed by the 1854 Earthquake Tsunami in Suruga Bay, Central Japan" (PDF). ISET Journal of Earthquake Technology. 42 (4): 147–58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Murakami, H.; Ito S.; Hiraiwa Y.; Shimada T. (1995). "Re-examination of historical tsunamis in Shikoku Island, Japan". In Tsuchiya Y. & Shutō N. (ed.). Tsunami: progress in prediction, disaster prevention, and warning. Springer. p. 336. ISBN 9780792334835. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- 安政南海地震 Archived 9 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in Japanese)

- Barkan, R.; ten Brink, U. (2010), "Tsunami Simulations of the 1867 Virgin Island Earthquake: Constraints on Epicenter Location and Fault Parameters" (PDF), Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 100 (3): 995–1009, Bibcode:2010BuSSA.100..995B, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.544.6624, doi:10.1785/0120090211, archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2017, retrieved 3 September 2017

- "The 1868 Arica Tsunami". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- Lander, pp. 44–45.

- Delouis, B.; Pardo, M.; Legrand, D.; Monfret, T. (2009). "The Mw 7.7 Tocopilla Earthquake of 14 November 2007 at the Southern Edge of the Northern Chile Seismic Gap: Rupture in the Deep Part of the Coupled Plate Interface" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 99 (1): 87–94. Bibcode:2009BuSSA..99...87D. doi:10.1785/0120080192. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- Tufty, Barbara (1978). 1001 questions answered about earthquakes, avalanches, floods, and other natural disasters. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 100–01. ISBN 978-0-486-23646-9.

- Aaron Micallef, Sebastian F. L. Watt, Christian Berndt, Morelia Urlaub, Sascha Brune, Ingo Klaucke, Christoph Böttner, Jens Karstens, and Judith Elger, "An 1888 Volcanic Collapse Becomes a Benchmark for Tsunami Models," eos.org, 17 October 2017 Retrieved 29 June 2020

- "Ritter Island". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- "Ritter Island – Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Ward, S.N. & Day, S. (2003). "Ritter Island Volcano—lateral collapse and the tsunami of 1888" (PDF). Geophysical Journal International. 154 (3): 891–902. Bibcode:2003GeoJI.154..891W. doi:10.1046/j.1365-246X.2003.02016.x. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- Ritter Island at Volcano World

- Starheim, Ottar (2009). "Lodalsulukkene 1905 og 1936". In Bjerkaas, Hans-Tore (ed.). Sogn og Fjordane Fylkesleksikon (in Norwegian). NRK. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- "The Lodal catastrophes". Nord Fjord.

- Lander, p. 57.

- Martin S.S.; Li L.; Okal E.A.; Morin J.; Tetteroo A.E.G.; Switzer A.D.; Sieh K.E. (26 March 2019). "Reassessment of the 1907 Sumatra "Tsunami Earthquake" Based on Macroseismic, Seismological, and Tsunami Observations, and Modeling". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 176 (7): 2831–2868. Bibcode:2019PApGe.176.2831M. doi:10.1007/s00024-019-02134-2. ISSN 1420-9136.

- "The world's worst natural disasters – CBC News". Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Hornback, M. J.; Mondziel, S. A.; Grindlay, N. R.; Frohlich, C.; Mann, P. (2008), "Did a submarine landslide trigger the 1918 Puerto Rico tsunami?" (PDF), Science of Tsunami Hazards, 27 (2): 22–31, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 30 June 2015

- Fine, I.V.; Rabinovich A.B.; Bornhold B.D.; Thomson R.E.; Kulikov E.A. (2005). "The Grand Banks landslide-generated tsunami of November 18, 1929: preliminary analysis and numerical modeling" (PDF). Marine Geology. 215 (1–2): 45–57. Bibcode:2005MGeol.215...45F. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2004.11.007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Okal, E. A.; Borrero, J. C. (2011), "The 'tsunami earthquake' of 1932 June 22 in Manzanillo, Mexico: seismological study and tsunami simulations", Geophysical Journal International, 187 (3): 1443–59, Bibcode:2011GeoJI.187.1443O, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05199.x

- Schiller, Bill (15 March 2011). "A story of survival rises from the ruins of a fishing village". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Furseth, Astor (1985): Dommedagsfjellet. Tafjord 1934. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Store norske leksikon. "Tafjord" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Starheim, Ottar (2009). "Lodalsulukkene 1905 og 1936". In Bjerkaas, Hans-Tore (ed.). Sogn og Fjordane Fylkesleksikon (in Norwegian). NRK. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- Lander, pp. 61–64.

- Rajendran, C. P.; Ramanamurthy, M. V.; Reddy, N. T.; Rajendran, K. (2008). "Hazard implications of the late arrival of the 1945 Makran tsunami". Current Science. 95 (12): 1739–1743. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- "1945 Makran Tsunami". Indian Ocean Tsunami Information Center. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Okal, E. A.; Synolakis, C. E.; Uslu, B.; Kalligeris, N.; Voukouvalas, E. (2009), "The 1956 earthquake and tsunami in Amorgos, Greece" (PDF), Geophysical Journal International, 178 (3): 1533–54, Bibcode:2009GeoJI.178.1533O, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.2009.04237.x

- "Emergency & Disasters Data Base". CRED. Archived from the original on 11 August 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- "Historic Earthquakes: Rat Islands, Alaska". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Guesmia, M.; Heinrich, Ph.; Mariotti, C. (1998), "Numerical Simulation of the 1969 Portuguese Tsunami by a Finite Element Method", Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 17 (1): 31–46, doi:10.1023/A:1007920617540

- Voight, B.; Janda, R. J.; Glicken, H>; Douglass, P. M. (25 May 2015). "Nature and mechanics of the Mount St Helens rockslide-avalanche of 18 May 1980". Géotechnique. 33 (3): 243–273. doi:10.1680/geot.1983.33.3.243.

- "Tsunamis and Earthquakes – 1998 Papua New Guinea tsunami Descriptive Model – USGS WCMG". Walrus.wr.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 17 August 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- "Comments for the Tsunami Runup at Degirmendere". NGDC/WDS Tsunami Event Database. NGDC. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- "Comments for the Tsunami Runup at Ulasli". NGDC/WDS Tsunami Event Database. NGDC. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Roberts, Nicholas; J. McKillop, Robin; S. Lawrence, Martin; F. Psutka, John; Clague, John; Brideau, Marc-Andre; Ward, Brent (1 January 2013). "Impacts of the 2007 Landslide-Generated Tsunami in Chehalis Lake, Canada". Landslide Science and Practice. 6. pp. 133–140. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31319-6_19. ISBN 978-3-642-31318-9. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2017 – via ResearchGate.

- "Ice breaks off glacier after Christchurch quake – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- "Quake shakes 30m tonnes of ice off glacier – National – NZ Herald News". Nzherald.co.nz. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 March 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Japan Hit by 33ft Tsunami". Daily Express. London. 11 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "Japan Earthquake: before and after – ABC News". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Jón Kristinn Helgason, Sveinn Brynjólfsson, Tómas Jóhannesson, Kristín S. Vogfjörð, Harpa Grímsdóttir; Ásta Rut Hjartardóttir, Þorsteinn Sæmundsson, Ármann Höskuldsson, Freysteinn Sigmundsson, Hannah Reynolds (5 August 2014). "Frumniðurstöður rannsókna á berghlaupi í Öskju 21. júlí 2014". Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kokkegård, H. (19 June 2017). "Geus: Uklart, om jordskælv udløste grønlandsk tsunami [Unclear if earthquake caused Greenlandic tsunami]". Ingeniøren. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "After recon trip, researchers say Greenland tsunami in June reached 300 feet high". Georgia Institute of Technology. 25 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Sulawesi quake: Death toll crosses 1,200 as rescuers race to reach victims". straitstimes.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "BMKG Pastikan Tsunami 1,5 Meter hingga 2 Meter Melanda Palu dan Donggala". KOMPAS (in Indonesian). 28 September 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "Tsunami terjang Selat Sunda, korban diperkirakan terus bertambah". BBC (in Indonesian). 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- Ramdhani, Jabbar (23 December 2018). "Update Terkini BMKG: Yang Terjadi di Anyer Bukan Tsunami karena Gempa". detiknews (in Indonesian). Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "22-23 Dec 2018 eruption & tsunami in aluiakbe Krakatoa – updates". Volcano Discovery. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "Tsunami in Banten, Lampung kills at least 20: Disaster agency". The Jakarta Post. 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "Indonesia 'volcano tsunami': At least 43 dead and 600 injured amid Krakatoa eruption". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "Number of people injured by tsunami soars to 7,200". Straits Times. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Christensen, Doug. "The Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964". Alaska Earthquake Center. Geophysical Institute, UAF. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Joint evaluation of the international response to the Indian Ocean tsunami: Synthesis Report" (PDF). TEC. July 2006. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

External links

- Tinti S., Maramai A., Graziani L. (2007). The Italian Tsunami Catalogue (ITC), Version 2 (Windows software database)