Treaty of Nice

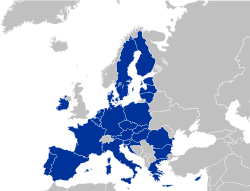

The Treaty of Nice was signed by European leaders on 26 February 2001 and came into force on 1 February 2003.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

| Type | Amender of previous treaties |

| Drafted | 11 December 2000 |

| Signed | 26 February 2001 |

| Location | Nice, France |

| Effective | 1 February 2003 |

| Signatories | |

| Citations | Prior amendment treaty: Amsterdam Treaty (1997) Subsequent amendment treaty: Lisbon Treaty (2007) |

| Languages | |

After amendments made by the Nice Treaty: Consolidated version of EURATOM treaty (2001) Consolidated version of TECSC (2001) -expired 2002 Consolidated version of TEC and TEU (2001) | |

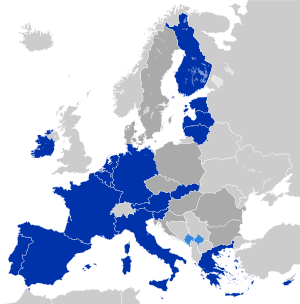

It amended the Maastricht Treaty (or the Treaty on European Union) and the Treaty of Rome (or the Treaty establishing the European Community which, before the Maastricht Treaty, was the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community). The Treaty of Nice reformed the institutional structure of the European Union to withstand eastward expansion, a task which was originally intended to have been done by the Amsterdam Treaty, but failed to be addressed at the time.

The entry into force of the treaty was in doubt for a time, after its initial rejection by Irish voters in a referendum in June 2001. This referendum result was reversed in a subsequent referendum held a little over a year later.

Provisions of the treaty

The Nice Treaty was attacked by many people as a flawed compromise. Germany had demanded that its greater population be reflected in a higher vote weighting in the Council; this was opposed by France, who insisted that the symbolic parity between France and Germany be maintained. The Commission had proposed to replace the old weighted voting system with a double majority system which would require those voting in favour to represent a majority of both member states and population for a proposal to be approved.[1] This was also rejected by France for similar reasons. A compromise was reached, which provided for a double majority of Member States and votes cast, and in which a Member State could optionally request verification that the countries voting in favour represented a sufficient proportion of the EU's population.

| Country | Voting weight |

Pop. (Mio.) |

Rel.[5] weight |

| Germany | 29 | 82.0 | 1.00 |

| United Kingdom | 29 | 59.4 | 1.38 |

| France | 29 | 59.1 | 1.39 |

| Italy | 29 | 57.7 | 1.42 |

| Spain | 27 | 39.4 | 1.94 |

| Poland | 27 | 38.6 | 1.98 |

| Romania | 14 | 22.3 | 1.78 |

| Netherlands | 13 | 15.8 | 2.33 |

| Greece | 12 | 10.6 | 3.20 |

| Czech Republic | 12 | 10.3 | 3.29 |

| Belgium | 12 | 10.2 | 3.33 |

| Hungary | 12 | 10.0 | 3.39 |

| Portugal | 12 | 9.9 | 3.42 |

| Sweden | 10 | 8.9 | 3.18 |

| Austria | 10 | 8.1 | 3.49 |

| Bulgaria | 10 | 7.7 | 3.67 |

| Slovakia | 7 | 5.4 | 3.67 |

| Denmark | 7 | 5.3 | 3.73 |

| Finland | 7 | 5.2 | 3.81 |

| Lithuania | 7 | 3.7 | 5.35 |

| Ireland | 7 | 3.7 | 5.35 |

| Latvia | 4 | 2.4 | 4.71 |

| Slovenia | 4 | 2.0 | 5.67 |

| Estonia | 4 | 1.4 | 8.08 |

| Cyprus | 4 | 0.8 | 14.14 |

| Luxembourg | 4 | 0.4 | 28.28 |

| Malta | 3 | 0.4 | 21.26 |

| Total | 345 | 490 | |

The Treaty provided for an increase after enlargement of the number of seats in the European Parliament to 732, which exceeded the cap established by the Treaty of Amsterdam.

The question of a reduction in the size of the European Commission after enlargement was resolved to a degree — the Treaty providing that once the number of Member States reached 27, the number of Commissioners appointed in the subsequent Commission would be reduced by the Council to below 27, but without actually specifying the target of that reduction. As a transitional measure it specified that after 1 January 2005, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain would each give up their second Commissioner.

The Treaty provided for the creation of subsidiary courts below the European Court of Justice and the Court of First Instance (now the General Court) to deal with special areas of law such as patents.

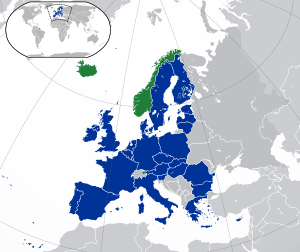

The Treaty of Nice provides for new rules on closer co-operation, the rules introduced in the Treaty of Amsterdam being viewed as unworkable, and hence these rules have not yet been used.

In response to the failed sanctions against Austria following a coalition including Jörg Haider's party having come to power, and fears about possible future threats to the stability of the new member states to be admitted in enlargement, the Treaty of Nice added a preventive mechanism to sanctions against a Member State that was created by the Amsterdam Treaty.[6]

The Treaty also contained provisions to deal with the financial consequences of the expiry of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) treaty (Treaty of Paris (1951)).

The Irish referendums

Under the current rules for the amendment of the Treaties, the Treaties can only be amended by a new Treaty, which must be ratified by each of the Member States to enter into force.

In all the EU member states the Treaty of Nice was ratified by parliamentary procedure, except in Ireland where, following the decision of the Irish supreme court in Crotty v. An Taoiseach, any amendments that result in a transfer of sovereignty to the European Union require a constitutional amendment. Ireland's Constitution can only be amended by a referendum.

First referendum

To the surprise of the Irish government and the other EU member states, Irish voters rejected the Treaty of Nice in June 2001. The turnout itself was low (34%), partly a result of the failure of the major Irish political parties to mount a strong campaign on the issue, presuming that the Irish electorate would pass the Treaty as all previous such Treaties had been passed by big majorities. However, many Irish voters were critical of the Treaty contents, believing that it marginalised smaller states. Others questioned the impact of the Treaty on Irish neutrality. Other sections viewed the leadership of the Union as out of touch and arrogant, with the Treaty offering a perceived chance to 'shock' the European leadership into a greater willingness to listen to its critics. (A similar argument was made when Denmark initially voted down the Treaty of Maastricht.)

Second referendum

The Irish government, having obtained the Seville Declaration on Ireland's policy of military neutrality from the European Council, decided to have another referendum on the Treaty of Nice on Saturday, 19 October 2002. Two significant qualifications were included in the second proposed amendment, one requiring the consent of the Dáil for enhanced cooperation under the treaty, and another preventing Ireland from joining any EU common defence policy. A 'Yes' vote was urged by a massive campaign by the main parties and by civil society and the social partners, including campaigning through canvassing and all forms of media by respected pro-European figures like then EP president Pat Cox, former Czech president Václav Havel, former President of Ireland Patrick Hillery and former Taoiseach (prime minister) Dr. Garret FitzGerald. Prominent civil society campaigns on the Yes side included Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, the Labour Party, the Progressive Democrats, the Irish Alliance for Europe led by Professor Brigid Laffan and Adrian Langan, and Ireland for Europe led by Ciarán Toland. On the No Side, the principal campaigns were those of the Green Party, Sinn Féin, Anthony Coughlan's National Platform, Justin Barrett's No to Nice campaign, and Roger Cole's Peace and Neutrality Alliance. The result was a 60% "Yes" vote on a near-50% turn-out.

By then all other EU member states had ratified the Treaty. Ratification by all parties was required by the end of the year, or else the Treaty would have expired.

Views of the treaty

Proponents of the Treaty claimed it was a utilitarian adjustment to cumbersome EU governing mechanisms and a required streamlining of the decision-making process, necessary to facilitate enlargement of the EU into Central and Eastern Europe. They claim that, consequently, the treaty was vitally important for the integration and future progress of these former Eastern Bloc countries. Many people who were in favour of greater scope and power of the EU project felt that it did not go far enough and that it would in any case be superseded by future treaties. Proponents differed in the extent to which enlargement may have proceeded without the Treaty: some claimed that the very future of the Union's growth—if not existence—was at stake, while others said that enlargement could have legally proceeded—albeit at a slower pace—without it.

Opponents of the Treaty claimed that it was a "technocratic" rather than "democratic" treaty, which would further diminish the sovereignty of national and regional parliaments, and would further concentrate power into a centralised and unaccountable bureaucracy. They also claimed that five applicant countries could have joined the EU without changing the EU's rules, and that others could have negotiated on an individual basis, something opponents to the treaty argued would have been to the applicants' advantage. They also claimed that the Treaty of Nice would create a two-tier EU, which might marginalise Ireland. Opponents pointed out that leading pro-treaty politicians had admitted that if referendums had been held in countries other than Ireland, it would probably have been defeated there as well.

Criticism

The Commission and the European Parliament were disappointed that the Nice intergovernmental conference (IGC) did not adopt many of their proposals for reform of the institutional structure or introduction of new Community powers, such as the appointment of a European Public Prosecutor. The European Parliament threatened to pass a resolution against the Treaty; although it has no formal power of veto, the Italian Parliament threatened that it would not ratify without the European Parliament's support. However, in the end this did not come to pass and the European Parliament approved the Treaty.

Many argue that the pillar structure, which was maintained by the Treaty, is overcomplicated; that the separate Treaties should be merged into one Treaty; that the three (now two) separate legal personalities of the Communities should be merged; and that the European Community and the European Union should be merged, with the European Union being endowed with legal personality. The German regions were also demanding a clearer separation of the powers of the Union from the Member States.

Nor did the Treaty of Nice deal with the question of the incorporation of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into the Treaty; that was also left for the 2004 IGC after the opposition of the United Kingdom.

Signatures

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

Withdrawal

At the end of January 2020 (GMT), the UK left the EU and so withdrew from this Treaty.

EU evolution timeline

Since the end of World War II, sovereign European countries have entered into treaties and thereby co-operated and harmonised policies (or pooled sovereignty) in an increasing number of areas, in the so-called European integration project or the construction of Europe (French: la construction européenne). The following timeline outlines the legal inception of the European Union (EU) ― the principal framework for this unification. The EU inherited many of its present responsibilities from, and the membership of the European Communities (EC), which were founded in the 1950s in the spirit of the Schuman Declaration.

| Legend: S: signing F: entry into force T: termination E: expiry de facto supersession Rel. w/ EC/EU framework: de facto inside outside |

[Cont.] | |||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom) | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | European Community (EC) | |||||||||||||||

| Schengen Rules | ||||||||||||||||

| [Cont.] | Terrorism, Radicalism, Extremism and Violence Internationally (TREVI) | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) | ||||||||||||||

| Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC) | ||||||||||||||||

Anglo-French alliance |

[Defence org. handed to NATO] | European Political Co-operation (EPC) | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | |||||||||||||

| [Tasks handed to EU] | ||||||||||||||||

| [Social, cultural tasks handed to CoE] | [Cont.] | |||||||||||||||

- ¹Although not EU treaties per se, these treaties affected the development of the EU defence arm, a main part of the CFSP. The Franco-British alliance established by the Dunkirk Treaty was de facto superseded by WU. The CFSP pillar was bolstered by some of the security structures that had been established within the remit of the 1955 Modified Brussels Treaty (MBT). The Brussels Treaty was terminated in 2011, consequently dissolving the WEU, as the mutual defence clause that the Lisbon Treaty provided for EU was considered to render the WEU superfluous. The EU thus de facto superseded the WEU.

- ²The treaties of Maastricht and Rome form the EU's legal basis, and are also referred to as the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), respectively. They are amended by secondary treaties.

- ³The European Communities obtained common institutions and a shared legal personality (i.e. ability to e.g. sign treaties in their own right).

- ⁴Between the EU's founding in 1993 and consolidation in 2009, the union consisted of three pillars, the first of which were the European Communities. The other two pillars consisted of additional areas of cooperation that had been added to the EU's remit.

- ⁵The consolidation meant that the EU inherited the European Communities' legal personality and that the pillar system was abolished, resulting in the EU framework as such covering all policy areas. Executive/legislative power in each area was instead determined by a distribution of competencies between EU institutions and member states. This distribution, as well as treaty provisions for policy areas in which unanimity is required and qualified majority voting is possible, reflects the depth of EU integration as well as the EU's partly supranational and partly intergovernmental nature.

See also

References

- Laursen, Finn, ed. (2005). The Treaty of Nice: Actor Preferences, Bargaining And Institutional Choice. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 393. ISBN 90-04-14820-5.

- Article 12 of the 2003 Act of Accession (OJ L 236, 23 September 2003, p. 33). The figures given in the Act of Accession were determined prior to the 2004 enlargement in a declaration attached to the Nice Treaty (OJ C 80, 10 March 2001, p 82).

- "EU voting row explained". British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 March 2004. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Baldwin, Richard; Widgrén, Mika (February 2005). "The Impact of Turkey's Membership on EU Voting" (PDF). CEPS Policy Brief. Centre for European Policy Studies (62): 11.

- The relative weight is a measure of how many Council votes a country has related to its population. In this instance, the German weight is taken to be 1.00 and as a reference to all others.

- Sadurski, Wojciech (2010). "Adding a Bite to a Bark? A Story of Article 7, the EU Enlargement, and Jörg Haider". Sydney Law School, University of Sydney. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

External links

- Summary of the Treaty

- Consolidated version of the Treaties

- Landmark EU treaty comes into effect - BBC News article dated February 1, 2003

- History of the European Union - Treaty of Nice

- Analysis of the voting weighs before and after, with 3D visualisation

- Book about the Treaty of Nice (also as PDF)

- Treaty of Nice European NAvigator