Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum (/kɑːrˈtuːm/ kar-TOOM;[5][6] Arabic: الخرطوم, romanized: Al-Khurṭūm) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan, the sixth-largest in Africa, the second-largest in North Africa, and the fourth-largest in the Arab world. Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile, flowing west from Lake Tana in Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as al-Mogran or al-Muqran (المقرن; English: "The Confluence"). From there, the Nile continues to flow north towards Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea.

Khartoum الخرطوم | |

|---|---|

Khartoum State | |

Khartoum at night | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "Triangular Capital" | |

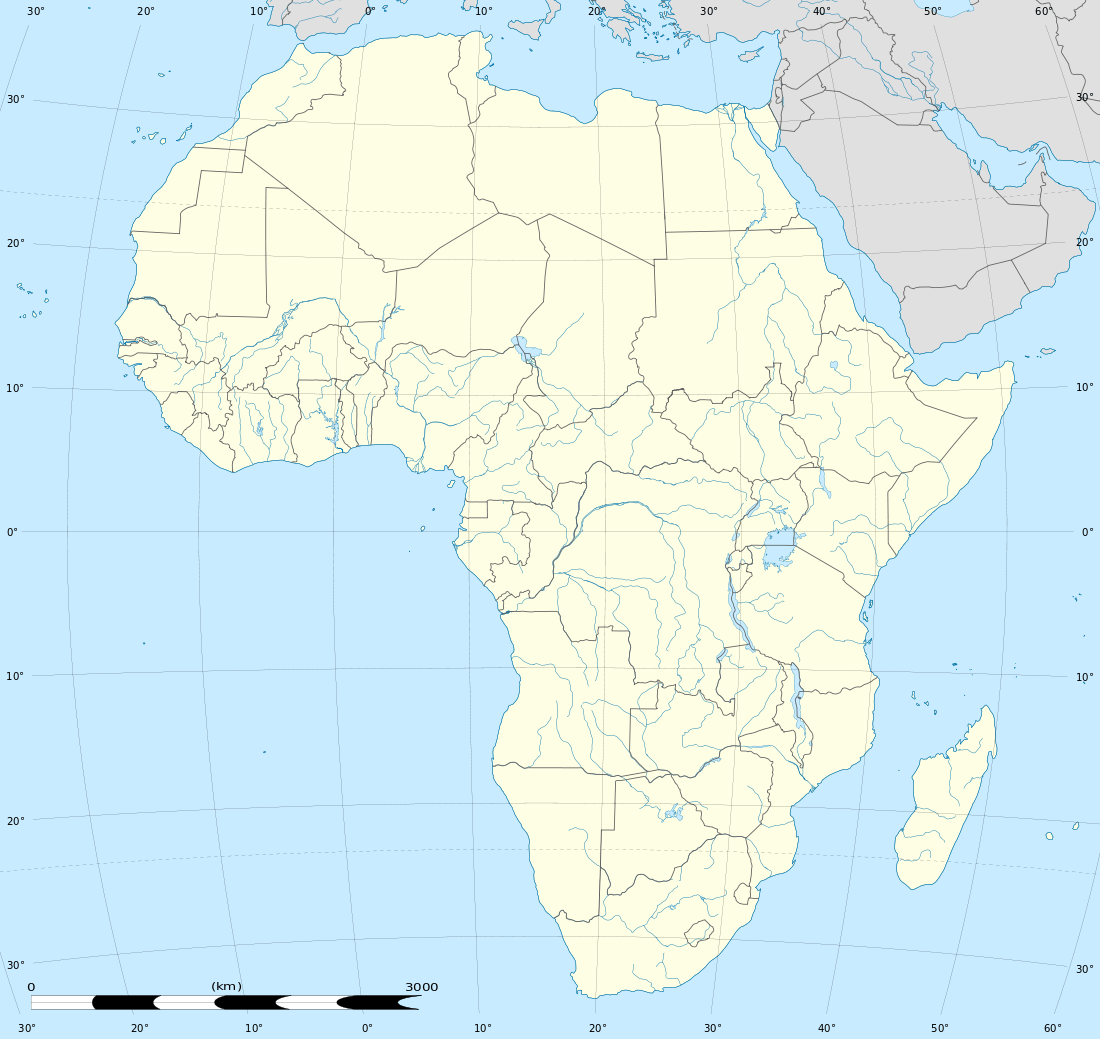

Khartoum Location in Sudan and Africa  Khartoum Khartoum (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 15°30′2″N 32°33′36″E[1] | |

| Country | Sudan |

| State | Khartoum |

| Area | |

| • Khartoum State | 22,142 km2 (8,549 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 381 m (1,250 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Khartoum State | 639,598 |

| • Urban | 5,490,000 |

| • Metro | 5,274,321 |

| Demonyms | Khartoumese, Khartoumian (the latter more properly designates a Mesolithic archaeological stratum) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

Divided by these two parts of the Nile, Khartoum is a tripartite metropolis with an estimated overall population of over five million people, consisting of Khartoum proper, and linked by bridges to Khartoum North (الخرطوم بحري al-Kharṭūm Baḥrī) and Omdurman (أم درمان Umm Durmān) to the west.

Khartoum was founded in 1821 as part of Ottoman Egypt, north of the ancient city of Soba. The Siege of Khartoum in 1884 led to the capture of the city by Mahdist forces and a massacre of the defending Anglo-Egyptian garrison. It was reoccupied by British forces in 1898 and served as the seat of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan government until 1956[7], when the city became the capital of an independent Sudan. The city has continued to experience unrest in modern times. Three hostages were killed during the Attack on the Saudi Embassy in Khartoum in 1973. The Justice and Equality Movement engaged in combat with Sudanese government forces in the city in 2008 as part of the War in Darfur. The Khartoum massacre occurred in 2019 amongst the Sudanese Revolution.

Khartoum is an economic and trade centre in Northern Africa, with rail lines from Port Sudan and El-Obeid. It is served by Khartoum International Airport, with another airport, Khartoum New International Airport, under construction. Several national and cultural institutions are located in Khartoum and its metropolitan area, including the National Museum of Sudan, the Khalifa House Museum, the University of Khartoum, and the Sudan University of Science and Technology.

Etymology

The origin of the word Khartoum is uncertain. One theory argues that it is derived from Arabic khurṭūm (خرطوم, "trunk" or "hose"), probably referring to the narrow strip of land extending between the Blue and White Niles.[8] Dinka scholars argue that the name derives from the Dinka words khar-tuom (Dinka-Bor dialect) or khier-tuom (as is the pronunciation in various Dinka Diaelects), translating to "place where rivers meet". This is supported by historical accounts which place the Dinka homeland in central Sudan (around present-day Khartoum) as recently as the 13th-17th centuries A.D.[9] Captain J.A. Grant, who reached Khartoum in 1863 with Captain Speke's expedition, thought the name was most probably from the Arabic qurtum (قرطم, "safflower", i.e., Carthamus tinctorius), which was cultivated extensively in Egypt for its oil to be used as fuel.[10] Some scholars speculate that the word derives from the Nubian word Agartum ("the abode of Atum"), the Nubian and Egyptian god of creation. Other Beja scholars suggest Khartoum is derived from the Beja word hartoom, "meeting".[11][12]

History

.svg.png)

Founding (1821–1899)

_b_617.jpg)

In 1821, Khartoum was established 24 kilometres (15 mi) north of the ancient city of Soba, by Ibrahim Pasha, the son of Egypt's ruler, Muhammad Ali Pasha, who had just incorporated Sudan into his realm. Originally, Khartoum served as an outpost for the Egyptian Army, but the settlement quickly grew into a regional centre of trade. It also became a focal point for the slave trade.[13] Later, it became the administrative center and official capital of Sudan.

On 13 March 1884, troops loyal to the Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad started a siege of Khartoum, against defenders led by British General Charles George Gordon. The siege ended in a massacre of the Anglo-Egyptian garrison when on 26 January 1885 the heavily-damaged city fell to the Mahdists.[14]

On 2 September 1898, Omdurman was the scene of the bloody Battle of Omdurman, during which British forces under Herbert Kitchener defeated the Mahdist forces defending the city.[15]

Modern history (20th–21st centuries)

In 1973, the city was the site of an anomalous hostage crisis in which members of Black September held 10 hostages at the Saudi Arabian embassy, five of them diplomats. The US ambassador, the US deputy ambassador, and the Belgian chargé d'affaires were murdered. The remaining hostages were released. A 1973 United States Department of State document, declassified in 2006, concluded: "The Khartoum operation was planned and carried out with the full knowledge and personal approval of Yasser Arafat."[16]

In 1977, the first oil pipeline between Khartoum and the Port of Sudan was completed.[17]

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Khartoum was the destination for hundreds of thousands refugees fleeing conflicts in neighboring nations such as Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Many Eritrean and Ethiopian refugees assimilated into society, while others settled in large slums at the outskirts of the city. Since the mid-1980s, large numbers of refugees from South Sudan and Darfur fleeing the violence of the Second Sudanese Civil War and Darfur conflict have settled around Khartoum.

In 1991, Osama bin Laden purchased a house in the affluent al-Riyadh neighborhood of the city and another in Soba. He lived there until 1996, when he was banished from the country. Following the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, the United States accused bin Laden's al-Qaeda group and, on 20 August, launched cruise missile attacks on the al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum North. The destruction of the factory produced diplomatic tension between the U.S. and Sudan. The factory ruins are now a tourist attraction.[18]

In November 1991, the government of President Omar al-Bashir sought to remove half the population from the city. The residents, deemed "squatters", were mostly southern Sudanese who the government feared could be potential rebel sympathizers. Around 425,000 people were placed in five "Peace Camps" in the desert an hour's drive from Khartoum. The camps were watched over by heavily armed security guards, many relief agencies were banned from assisting, and "the nearest food was at a market four miles away, a vast journey in the desert heat." Many residents were reduced to having only burlap sacks as housing. The intentional displacement was part of a large urban renewal plan backed by the housing minister, Sharaf Bannaga.[19][20][21]

The sudden death of SPLA head and vice-president of Sudan, John Garang, at the end of July 2005, was followed by three days of violent riots in the capital. The riots finally died down after Southern Sudanese politicians and tribal leaders sent strong messages to the rioters. The situation could have been much more dire; even so, the death toll was at least 24, as youths from southern Sudan attacked northern Sudanese and clashed with security forces.[22]

The Organisation of African Unity summit of 18–22 July 1978 was held in Khartoum, during which Sudan was awarded the OAU presidency.[23] The African Union summit of 16–24 January 2006 was held in Khartoum.[24]

The Arab League summit of 29th of August 1967 was held in Khartoum as the fourth Arab League Summit. The Arab League summit of 28–29 March 2006 was held in Khartoum, during which the Arab League awarded Sudan the Arab League presidency.[25]

On 10 May 2008, the Darfur rebel group, Justice and Equality Movement, moved into the city, where they engaged in heavy fighting with Sudanese government forces. Their soldiers included minors, and their goal was to topple Omar al-Bashir's government, though the Sudanese government succeeded in beating back the assault.[26][27][28]

On 23 October 2012, an explosion at the Yarmouk munitions factory killed two people and injured another person. The Sudanese government has claimed that the explosion was the result of an Israeli airstrike.[29]

On 3 June 2019, Khartoum was the site of the Khartoum massacre, where over 100 dissidents were murdered (the government said 61 were killed), hundreds more injured and 70 women raped by Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in order to forcefully disperse the peaceful protests calling for civilian government.[30]

On 1 July 2020, activists demanded that al-Zibar Basha street in Khartoum be renamed. Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur was a slave trader and the al-Zibar Basha street leads to the military base where the 2019 Khartoum massacre took place.[31]

Geography

Location

Khartoum is located in the middle of the populated areas in Sudan, at almost the northeast center of the country between 15 and 16 degrees latitude north, and between 31 and 32 degrees longitude east.[32] Khartoum marks the convergence of the White Nile and the Blue Nile, where they join to form the bottom of the leaning-S shape of the main Nile (see map, upper right) as it zigzags through northern Sudan into Egypt at Lake Nasser.

Khartoum is relatively flat, at elevation 385 m (1,263 ft),[32] as the Nile flows northeast past Omdurman to Shendi, at elevation 364 m (1,194 ft)[33][34]about 101 miles (163 km) away.

Climate

Khartoum features a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) with a dry season occurring during winter, typical of the Saharo-Sahelian zone, which marks the progressive passage between the Sahara Desert's vast arid areas and the Sahel's vast semi-arid areas. The climate is extremely dry for most of the year, with about eight months when average rainfall is lower than 5 mm (0.20 in). The very long dry season is itself divided into a hot, very dry season between November and February, as well as a very hot, dry season between March and May. During this part of the year, hot, dry continental trade winds from deserts sweep over the region such as the harmattan (a northerly or northeasterly wind); the weather is stable and very dry. The very irregular, very brief, rainy season lasts about 1 month as the maximum rainfall is recorded in August, with about 75 mm (3.0 in). The rainy season is characterized by a seasonal reverse of wind regimes, when the Intertropical Convergence Zone goes northerly. Average annual rainfall is very low, with only 121.3 mm (4.78 in) of precipitation. Khartoum records on average six days with 10 mm (0.39 in) or more and 19 days with 1 mm (0.039 in) or more of rainfall. The highest temperatures occur during two periods in the year: the first at the late dry season, when average high temperatures consistently exceed 40 °C (104 °F) from April to June, and the second at the early dry season, when average high temperatures exceed 39 °C (102 °F) in September and October months. Khartoum is one of the hottest major cities on Earth, with annual mean temperatures hovering around 30 °C (86 °F). The city also has hot winters. In no month does the average monthly high temperature fall below 30 °C (86 °F). This is something not seen in other major cities with hot desert climates such as Riyadh, Baghdad and Phoenix. Temperatures cool off enough during the night, with Khartoum's lowest average low temperature of the year just above 15 °C (59 °F).[35]

| Climate data for Khartoum (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.7 (103.5) |

42.5 (108.5) |

45.2 (113.4) |

46.2 (115.2) |

46.8 (116.2) |

46.3 (115.3) |

44.5 (112.1) |

43.5 (110.3) |

44.0 (111.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

46.8 (116.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.7 (87.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

36.5 (97.7) |

40.4 (104.7) |

41.9 (107.4) |

41.3 (106.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.7 (101.7) |

39.3 (102.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

37.0 (98.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.9 (89.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.5 (90.5) |

32.4 (90.3) |

28.1 (82.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.9 (0.15) |

4.2 (0.17) |

29.6 (1.17) |

48.3 (1.90) |

26.7 (1.05) |

7.8 (0.31) |

0.7 (0.03) |

0.0 (0.0) |

121.3 (4.78) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 27 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 19 | 28 | 43 | 49 | 40 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 29 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 316.2 | 296.6 | 316.2 | 318.0 | 310.0 | 279.0 | 269.7 | 272.8 | 273.0 | 306.9 | 303.0 | 319.3 | 3,580.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 8.1 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 9.8 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation,[36] NOAA (extremes and humidity 1961–1990)[37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[38] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| City | Metropolitan area | |

| 1907[39] | 69,349 | n.a. |

| 1956 | 93,100 | 245,800 |

| 1973 | 333,906 | 748,300 |

| 1983 | 476,218 | 1,340,646 |

| 1993 | 947,483 | 2,919,773 |

| 2008 Census Preliminary | 3,639,598 | 5,274,321 |

Economy

_003.jpg)

After the signing of the historic Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the government of Sudan and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLA), the Government of Sudan began a massive development project.[40][41] In 2007, the biggest projects in Khartoum were the Al-Mogran Development Project, two five-star hotels, a new airport, Mac Nimir Bridge (finished in October 2007) and the Tuti Bridge that links Khartoum to Tuti Island.

In the 21st century, Khartoum developed based on Sudan's oil wealth (although the independence of South Sudan in 2011 affected the economy of Sudan negatively[42]). The center of the city has tree-lined streets. Khartoum has the highest concentration of economic activity in the country. This has changed as major economic developments take place in other parts of the country, like oil exploration in the South, the Giad Industrial Complex in Al Jazirah state and White Nile Sugar Project in Central Sudan, and the Merowe Dam in the North.

Among the city's industries are printing, glass manufacturing, food processing, and textiles. Petroleum products are now produced in the far north of Khartoum state, providing fuel and jobs for the city. One of Sudan's largest refineries is located in northern Khartoum.[42]

Retailing

The Souq Al Arabi is Khartoum's largest open air market. The "souq" is spread over several blocks in the center of Khartoum proper just south of the Great Mosque (Mesjid al-Kabir) and the minibus station. It is divided into separate sections, including one focused entirely on gold.[43]

Al Qasr Street and Al Jamhoriyah Street are considered the most famous high streets in Khartoum State.

Afra Mall is located in the southern suburb Arkeweet. The Afra Mall has a supermarket, retail outlets, coffee shops, a bowling alley, movie theaters, and a children's playground.

In 2011, Sudan opened the Hotel Section and part of the food court of the new, Corinthia Hotel Tower. The Mall/Shopping section is still under construction.

Education

Khartoum is the main location for most of Sudan's top educational bodies. There are four main levels of education:

- Kindergarten and day-care. It begins in the age of 3–4, consists of 1-2 grades, (depending on the parents).

- Elementary school. The first grade pupils enter at the age of 6-7. It consists of 8 grades, each year there is more academic efforts and main subjects added plus more school methods improvements. By the 8th grade a student is 13–14 years old ready to take the certificate exams and entering high school.

- Upper second school and high school. At this level the school methods add some main academic subjects such as chemistry, biology, physics, and geography. There are three grades in this level. The students' ages are about 14–15 to 17–18.

- Higher education. There are many universities in Sudan such as the university of Khartoum. Some foreigners attend universities there, as the reputation of the universities are very good and the living expenses are low compared to other countries.

The education system in Sudan went through many changes in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[44][45][46]

High schools

- Khartoum Old High Secondary School for Boys

- Khartoum Old High Secondary School for Girls

- The British Educational Schools (BES)[47]

- Khartoum American School, KAS, established in 1957.

- Khartoum International Community School, KICS, established in 2004.

- Unity High School.[48]

- Suliman Hussein Academy

- Comboni and St. Francis, Khartoum new high secondary school for boys

- Khartoum International preparatory school (KIPS)|Khartoum International preparatory school, established in 1928.

- Qabbas Private International Schools

- Riad English School, established 1987

- Nile Valley School, founded 2012 [49]

- Mohamed Hussein High Secondary School for Boys in Omdurman

Universities and higher institutes in Khartoum

| Educational institution | Type | Website |

|---|---|---|

| University of Khartoum Founded as Gordon Memorial College in 1902, it was later renamed to share the name of the city in the 1930s | Public university | https://web.archive.org/web/20180711215331/http://www.uofk.edu/ |

| Academy of Engineering Sciences founded as Academy of Electrical Engineering in 2002 | Private university | https://web.archive.org/web/20181011004131/http://www.aes.edu.sd/ |

| Al-Neelain University | Public university | http://www.neelain.edu.sd |

| Al Zaiem Alazhari University | Public university | https://web.archive.org/web/20150405095256/http://www.aau.edu.sd/ |

| Bahri University, formally Juba University before the separation and Juba University returned to the South | Public university | |

| Omdurman Islamic University, | Public university | |

| International University of Africa | Public university | https://web.archive.org/web/20170717050156/http://www.iua.edu.sd/ |

| Nile Valley University | Public university | |

| Open University of Sudan | Public university | http://www.ous.edu.sd |

| Public Health Institute, post-graduate institution operated by the Ministry of Health | Public university | http://www.phi.edu.sd |

| Sudan University of Science and Technology, one of the leading engineering and technology schools in Sudan, founded in 1932 as Khartoum Technical Institute and has been given its present name in 1991 | Public university | http://www.sustech.edu |

| AlMughtaribeen University | Private university | https://web.archive.org/web/20191221175123/http://www.mu.edu.sd/ |

| Bayan College for Science & Technology | Private university | https://web.archive.org/web/20110920215435/http://www.bayantech.edu/ |

| Canadian Sudanese College | Private university | http://www.ccs.edu.sd |

| Comboni College for Science and Technology | Private universities | http://www.combonikhartoum.com |

| Future University of Sudan, the first specialized university for ICT inter-related studies in Sudan, founded by Dr. Abubaker Mustafa. | Private universities | http://www.futureu.edu.sd |

| National College for Medical & Technical Studies | Private university | https://web.archive.org/web/20131203001023/http://www.nc.edu.sd/ |

| National Ribat University | Private university | https://web.archive.org/web/20160411212315/http://ribat.edu.sd/ |

| University of Medical Sciences and Technology (UMST) founded in 1996 by Prof. Mamoun Humaida as Academy of Medical Science & Technology | Private universities | |

| Omdurman Al-ahlia University | Private university founded in 1985 |

Transportation

Air

Khartoum is home to the largest airport in Sudan, Khartoum International Airport. It is the main hub for Sudan Airways, Sudan's main carrier. The airport was planned for the Southern outskirts of the city; but with Khartoum's rapid growth and consequent urban sprawl, the airport is still located in the heart of the city.

Bridges

Bridges over the Blue Nile connecting Khartoum to Khartoum North:

- Mac Nimir Bridge

- Blue Nile Road & Railway Bridge

- Cooper Bridge, also known as The Armed Forces Bridge

- Elmansheya Bridge

Bridges over the White Nile, connecting Khartoum to Omdurman:

- Omdurman Bridge

- Victory Bridge

- Al-Dabbasin Bridge

Bridges connecting Tuti Island:

- Tuti Bridge

- Tuti North Bridge

Rail

Khartoum has rail lines from Wadi Halfa, Port Sudan on the Red Sea, and El Obeid. All are operated by Sudan Railways. Some lines also extended to some parts of south Sudan

Architecture

Architecture of Khartoum cannot be identified by one style or even two styles; it is as diverse as its culture, where 597 different cultural groups meet. In this article are 10 buildings of Khartoum to showcase this diversity in buildings’ shapes, materials, treatments. Sudan was home to numerous ancient civilizations, such as the Kingdom of Kush, Kerma, Nobatia, Alodia, Makuria, Meroë and others, most of which flourished along the Nile. During the pre-dynastic period Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were identical, simultaneously evolved systems of Pharaonic kingship by 3300 BC.

In response to the worldwide deterioration of the environment and the increase in pollution levels, there has been a strong movement towards sustainable architecture across the globe. This movement has received attention and concern from governments as well as private sectors. In the past decades, Sudan has seen a huge surge in infrastructure and technology, which has led to many new and innovative building concepts, ideas and construction techniques. There is now a constant flow of new projects arising, thus leading to a new, transformed, modernised form of architecture. [52]

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Muslim mosques.[53][54] There are also Christian churches and temples : Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Khartoum (Catholic Church), Sudan Interior Church (Baptist World Alliance), Presbyterian Church in Sudan (World Communion of Reformed Churches).

The Great Masjid

The Great Masjid Masjid Shahid

Masjid Shahid Faruq Mosque

Faruq Mosque- Siadah Sanhory Mosque in Manshiya

_001.jpg)

Culture

Museums

The largest museum in Sudan is the National Museum of Sudan.[55] Founded in 1971, it contains works from different epochs of Sudanese history. Among the exhibits are two Egyptian temples of Buhen and Semna,[56] originally built by Queen Hatshepsut and Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, respectively, but relocated to Khartoum upon the flooding of Lake Nasser.

The Republican Palace Museum,[57] opened in 2000, is located in the former Anglican All Saints' cathedral[58] on Sharia al-Jama'a, next to the historical Presidential Palace.

The Ethnographic Museum[59] is located on Sharia al-Jama'a, close to the Mac Nimir Bridge.

Botanical gardens

Khartoum is home to a small botanical garden, in the Mogran district of the city.[60]

Clubs

Khartoum is home to several clubs such as the Blue Nile Sailing Club,[61] the German Club, the Greek Hotel,[62] the Coptic Club, the Syrian Club and the International Club.[63] There are also two football clubs situated in Khartoum – Al Khartoum SC[64] and Al Ahli Khartoum.[65]

International relations

| Some roads and streets of Khartoum | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

See also

- Al-Mogran Development Project

- Khartoum, a 1966 film starring Charlton Heston and Laurence Olivier

- Al Amarat (Khartoum)

- Khartoum Zoo

- St. Matthew's Cathedral, Khartoum

- List of high schools in Sudan

References

- "Where is Khartoum, The Sudan?". worldatlas.com. 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- http://www.citypopulation.de/Sudan.html

- "Sudan Facts on Largest Cities, Populations, Symbols - Worldatlas.com". www.worldatlas.com. 7 April 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Demographia World Urban Areas (PDF) (14th ed.). Demographia. April 2018. p. 66. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Khartoum". Dictionary.reference.com.

- "Khartoum". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- "Khartoum | Location, Facts, & History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Beswick, Stephanie (2013). Sudan's Blood Memory: The Legacy of War, Ethnicity, and Slavery in Early South Sudan. p. 39. ISBN 9781580461511.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 194. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3.

- Walkley, C. E. J. (1935). "The Story of Khartoum" [2017-01-01]. Sudan Notes and Records. University of Khartoum. 18 (2): 221–241. JSTOR 41710712.

- "Beja scholars and the creativity of powerlessness". Passages. University of Michigan Library.

- Hasan Shukri (August 1966). "Khartoum and Tuti 'Shreen Munz Qarnan". Khartoum. 1 (11): 23.

- Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 139

- Hammond, Peter (2005). Slavery, Terrorism & Islam. Cape Town, South Africa: Christian Liberty Books.

- Britannica, Khartoum, britannica.com, USA, accessed on June 30, 2019

- "The Seizure of the Saudi Arabian Embassy in Khartoum" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- Minerals Yearbook. Bureau of Mines. 1995.

- Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian (2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 140. ISBN 9781610692489.

- 1966-, Peterson, Scott (2000). Me against my brother : at war in Somalia, Sudan, and Rwanda : a journalist reports from the battlefields of Africa. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415921988. OCLC 43287853.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Khartoum Squatters Forcibly Displaced". Christian Science Monitor. 31 March 1992. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Miller, Judith (9 March 1992). "Sudan Is Undeterred in Drive to Expel Squatters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "World | Africa | Riots after Sudan VP Garang dies". BBC News. 1 August 2005. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Harris, Gordon (1994). The Organization of African Unity. London, United Kingdom: Transaction Publishers. p. 29. ISBN 9781412830270.

- Staff. "Decisions & Declarations of the Assembly; African Union". African Union. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Hiro, Dilip (2013). A Comprehensive Dictionary of the Middle East. Olive Branch Press. ISBN 978-1566569040.

- "Curfew in capital as Sudanese army clash near Khartoum with Darfur rebels". Sudan Tribune. 10 May 2008.

- "Sudanese rebels 'reach Khartoum'". BBC News. 10 May 2008.

- "PHOTOS: Sudan capital after today's attack from Darfur JEM". Sudan Tribune. 10 May 2008.

- "Khartoum fire blamed on Israeli bombing". Al Jazeera. 25 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Burke, Jason; Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (13 July 2019). "Sudanese protesters demand justice following mass killings". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Burke, Samuel Okiror Jason; Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (1 July 2020). "'Decolonise and rename' streets of Uganda and Sudan, activists urge". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Khartoum Elevation (385m)". distancesto.com. 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Shendi Elevation (364m)". distancesto.com. 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Peel, M. C.; B. L. Finlayson; T. A. McMahon (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007.

- "World Weather Information Service – Khartoum". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- "Khartoum Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- "Klimatafel von Khartoum / Sudan" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 773.

- "Sudan and UNDP launch Millennium Goals project". Sudan Tribune. 5 September 2005. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Winter, Joseph (24 April 2007). "Khartoum booms as Darfur burns". BBC. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- "Country Analysis Brief: Sudan and South Sudan" (PDF). US Energy Information Administration. 3 September 2014. pp. 13–14 Oil refineries. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- "Sudan Shopping and Districts (Sudan, SD, North-East Africa)". World Guides. TravelSmart Ltd. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "وزارة تعليم عالي والبحث العلمي". حكومة سودان. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "وزارة التربية والتعليم". حكومة سودان. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- null (24 January 2012). The Status of the Education Sector in Sudan. The World Bank. pp. 159–189. doi:10.1596/9780821388570_ch07.

- "britisheducationsudan.com". britisheducationsudan.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- http://about.me/msaif30, MSaif / Original design: NVS Sudan -. "Nile Valley School - NVS in Brief". www.nilevalleyschool.com. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Sudanese higher education". Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Universities of Sudan Ahfad university for women". Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Archnet". archnet.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Britannica, Sudan, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- Shumba, Ano (28 October 2015). "Sudan National Museum ; Bio". Music in Africa. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "The Rescue of Nubian Monuments and Sites". UNESCO. 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Palace Museum". Presidency of the Republic of Sudan. 2016. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Designs for the Cathedral Church of All Saints, Khartoum..." RIBApix. 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Museums In Sudan". The Embassy of the Republic of Sudan. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Jibreel, T. J. O. (2010). "2 - Materials and Methods, Site of collection" (PDF). Two Ichneumonid Parasitoid Wasps Affecting Ficus sycamorus (L.) Fruits in Khartoum State (Thesis). Khartoum, Sudan: University of Khartoum department of Zoology. pp. 20–22.

- Uloth, Tony (18 January 2011). "The Blue Nile Sailing Club". The Melik Society. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Reuters.com". Africa.reuters.com. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Night clubs in Khartoum city". Fortune of Africa. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Former Ghana coach Kwesi Appiah takes over at SC Khartoum". BBC Sport. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Al Ahli Khartoum". FIFA (International Federation of Association Football). May 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "İstanbul'un Kardeş Şehir, İşbirliği Protokolleri ve Mutabakat Zaptı/İyi Niyet Mektupları" [Istanbul's Sister Cities, Cooperation Protocols and Memorandum of Understanding/Goodwill Letters] (in Turkish). İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "Sister Cities of Istanbul". Istanbul. 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Ethiopia's Capital Addis Ababa and Khartoum sign twin cities agreement". Nazret. 26 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi – Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Brasilia Global Partners". Internacional.df.gov.br. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Brotherhood & Friendship Agreements Signed Between Cairo & Arab Cities". Ministry of State for Administrative Development, Cairo Governorate. 2016. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Twinning document; Khartoum; Sudan; 14/2/1979

- "Sister Cities". Wuhan University. 2016. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Khartoum. |

![]()

- Kidnapped, tortured and thrown in jail: my 70 days in Sudan The Guardian, 2017