Joggins Formation

The Joggins Formation is a geologic formation in Nova Scotia. It preserves fossils dating back to the Carboniferous period, including Hylonomus, the earliest known reptile. In addition to fossils, the Joggins Formation was a valuable source of coal from the 17th century until the mid-20th century.

| Joggins Formation Stratigraphic range: Westphalian ~320–304 Ma | |

|---|---|

Tilted Joggins Formation sandstones | |

| Type | Formation |

| Unit of | Cumberland Group |

| Underlies | Polly Brook Formation |

| Overlies | Grand Anse & Little River Formations |

| Location | |

| Region | Nova Scotia |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Joggins, Nova Scotia |

| Named by | Walter A. Bell |

The Joggins Formation's spectacular coastal exposure, the Joggins Fossil Cliffs at Coal Mine Point, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.[1]

History

Early mining

Prior to European colonization, the Joggins Formation and surrounding territory was part of the Miꞌkmaꞌki, the traditional homeland of the Mi'kmaq nation.

French colonization of the Bay of Fundy began in 1604. Acadian miners from Beaubassin were the first Europeans to mine the cliffs at Joggins, taking advantage of the deposits less than a decade after Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin visited the site in 1686. Though Franquelin failed to make any mention of coal on his 1686 map, the document precisely detailed the geography of Chignecto Bay, and in a more detailed map published in 1702 he named the Joggins Cliffs "Ance au Charbon", or "Cove of Coal".[2] The explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac reported coal in Chignecto Bay in 1692. According to a travelogue written by Robert Hale in 1731, coal had been mined from the Fundy Seam - one of the thickest coal veins at Joggins - for at least thirty years at the time of his visit, and though there are only sporadic allusions to these pre-English operations in written records the government of Nova Scotia recognized Acadian brothers René and Bernard LeBlanc as being the first to discover coal at Joggins in 1701.

Eastern Acadia was captured by Great Britain in the War of the Spanish Succession and became the colony of Nova Scotia; the territory was formally ceded by France in 1713's Peace of Utrecht. Though the British had likely been mining at Joggins since the occupation began in 1710, the first official record of a coal mine at Joggins was made in 1720, when Governor of Nova Scotia Richard Philipps complained that the trade of coal between Nova Scotia and New England was going unregulated. Captain Andrew Belcher was one of the first merchants to transport coal from the Acadian-run mines in Joggins to the city of Boston, which was in the grips of a coal shortage in the 1710s, and after Belcher's death in 1717 his son Jonathan Belcher continued to trade along this route.

Henry Cope's mine

Governor Richard Philipps approved the creation of a government-owned coal mine at Joggins in 1730, to test the feasibility of both mining the resource and loading onto ships at the site. The project was led by Major Henry Cope, who invested in the mine with his own money and enlisted the help of Boston merchants to help establish the mine at what is today known as "Coal Mine Point". Coal was first harvested from Cope's mine in April 1731, and the Nova Scotia Council agreed to fund the project on 24 June 1731. Rather than load ships on-site, Cope had the coal transported by small boats from Joggins to a wharf at the mouth of Gran’choggin (present-day Downing Cove), a creek 11.3 km (6 mi) north of the mine. The name "Gran'choggin" represents the earlier known use of the name that would give rise to "Joggins", and is likely either a Romanization of the Mi'kmaq word "chegoggins" (English: "great encampment") or a portmanteau of the French word "grand" (English: "large") and Mi'kmaq word "choggin" (English: "creek"). Tides in the Bay of Fundy made docking in the Gran’choggin wharf difficult. Robert Hale arrived at the mine on 25 June 1731, recording in his travelogue that it took nineteen days for his schooner, the Cupid, to travel from Boston to Joggins, but it wasn't until 26 June that the ship was able to dock at Gran’choggin. Hale observed that a single miner could produce many chaldrons of coal each day, and that the Cupid was only the third ship to be loaded with coal from Cope's mine. The Cupid departed Joggins on 30 June, loaded with sixty tons of coal to be sold in Boston.

Henry Cope and his fellow developers were granted a land grant to develop a 16.19 km2 (4,000 ac) area around the mine on 21 June 1732. By the terms of the land grant, several names in the area were changed: the cliffs were renamed to "Adventurer’s Clifts" and Gran’choggin to "New Castle Cove". The land grant also stipulated that Cope pay a tax of one shilling and sixpence for every chaldron mined, send coal to Annapolis Royal to support military fortifications there, and begin construction of a town that would be named "Williamstown". To further support the venture, Cope demanded his crew of miners - about a dozen local Acadians - pay him rent in exchange for living on his land and working in his mine. The men conspired with their Mi'kmaq neighbours, and a group of three Mi'kmaq men raided Cope's land in 1732. The mine, storehouses, and Stanwell Hall (the first house built by Cope at the site) were destroyed in the attack, setting back operations substantially. Cope was soon unable to make funding for the project stretch, and after he defaulted on paying wages to his workers the mine was abandoned in November 1732. With the support of Governor Richard Philipps and James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, Cope attempted to restore the mine in January 1733. As a condition of his sponsors, Philipps was tasked with building blockhouses at the top of the cliffs to provide the site with military protection. Though at least some of the necessary fortifications were built, the project was again abandoned by Cope, ending all operations at the mine.

British settlement

British cartographers Edward Amherst and George Mitchell scouted the region in 1735, renaming the Adventurer's Clifts to "Grand Nyjagen".[3] Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia Lawrence Armstrong was insistent on having the area colonized by British settlers as it would secure their dominance in the region, which was still largely populated by the Mi'kmaq and Acadians. On 30 August 1736 a land grant was approved for the area around the northernmost reaches of the Grand Nyjaden for the purposes of establishing a town named "Norwich" (present-day Minudie), but the community failed to be established and was dissolved on 21 April 1760. Also in 1736, Captain Thomas Durrel produced his own map of Chignecto Bay in which he referred to the cliffs as "Sea Coal Cliff" and New Castle Cove as "Grand Jogin".

Acadian settlers continued to establish themselves in the region after the failed attempt to establish Norwich. In this period, the Acadians again began to mine for coal along the Grand Nyjagen cliffs and elsewhere, digging a line of coal pits from the coast to River Hebert, which came to be called the "Rivère des Mines des Hébert".

A geographical description of Nova Scotia was published in The London Magazine in 1749. The article commented on the abundance of coal in the Bay of Fundy, referenced Henry Cope's failed mining project, and assured readers that "a better use will, doubtless, be made of this treasure, when Nova Scotia itself comes to be inhabited".[2] Following Father Le Loutre's War, Beaubassin and other Acadian communities were destroyed by Jean-Louis Le Loutre as they retreated from the area, ending any ongoing mining efforts at the Grand Nyjagen. John Salusbury and Joshua Mauger both applied to mine coal from the site on 17 July 1750 and 24 June 1751, respectively, but were denied by the Board of Trade and Plantations as it would threaten the colonial economy, which relied on importing coal from Britain as per their system of mercantilism and foreign policy of preventing foreign industrialisation. The idea of mining locally was very attractive, as any firm exporting coal from Britain had to pay a duty of 11 shillings a ton, nearly twice the price that it sold for locally.[4]

Britain declared war on France on 17 May 1756, initiating the Seven Years' War. Governor Charles Lawrence petitioned the British government to reopen the Chignecto Bay mines in 1756 in order to fuel British regiments fighting in the Bay of Fundy region. The first British miners arrived at Grand Nyjagen in September 1757, selecting a mostly undisturbed section of cliff to dig into rather than Henry Cope's original mine.

After the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, coal mining at Grand Nyjagen again stopped entirely. A land grant which included the cliffs was given to Joseph Frederick Wallet Des Barres in 1764, but Des Barres proved to be an absentee landlord. Though Des Barres became an important figure elsewhere in Nova Scotia, his lack of interest in developing Grand Nyjagen led to the coal there being forgotten for six decades. Though most Acadians were deported during the Great Upheaval, a small number eventually returned and established short-lived villages in the area, including Shedd Fisheries at Mill Creek (present-day Minudie) and Joggin (present-day Maccan) at one of the River Hibert coal pits. While the Acadians did occasionally mine coal in this area, Des Barres only leased land to them if they promised to build grindstone quarries there. The most prosperous quarry was Bank Quarry (present-day Lower Cove), which operated for fifteen years between 1815 and 1830 and was the only source for Nova Scotia blue-grit, an important and popular grindstone. The owners of Bank Quarry - Joseph Read and John Seaman - used the wealth generated from their operation to open a second quarry (present-day Rockport) in New Brunswick. Read and Seaman's New Brunswick and Nova Scotia quarries came to be known as the "North Joggins" and "South Joggins", respectively, and the name "South Joggins" soon came to mean the cliffs in general. For thirty years between 1800 and 1830, shopkeeper William Harper managed a trade route using his schooner The Weasel, which traded basic commodities for grindstone at North Joggins and South Joggins before trading the grindstone to US and British colonists in the Passamaquoddy Bay region.

Despite a lack of any approval from Des Barres, British military forces mined for coal at Grand Nyjagen to supply Fort Cumberland in the period between the American Revolution and War of 1812, when it was feared the United States might try to annex the area and seize its coal deposits. One of the most plentiful mines in this period centred around the "King’s Vein" (now known as the "Joggins Seam"), named in honour of King George III. Ironically, George III did not ask that coal be included in the 1788 lease drawn up for his son Prince Frederick, which would have granted the Duke of York the mineral rights to all of Nova Scotia had it been put into effect.[4] It is unknown why the lease was not put into effect, though historians James Stewart Martell and Delphin Andrew Muise have suggested, respectively, that either the documents were lost or the value of Nova Scotian minerals was found to be disappointingly low. Though there were multiple small mines active along the cliffs in 1807, all had been abandoned by 1814. Des Barres's land became even more valuable in 1808 when a ban was put in place that prevented any future land grants from including mineral rights to coal, which was now deemed the sole property of the Crown; landowners, like Des Barres, who had received their land grants prior to this, were exempted. In 1819, British colonist Samuel McCully was the first to establish an official mine on Des Barres's property, extracting coal from Grand Nyjagen and sending it on to Saint John, New Brunswick, but McCully's mine shut down in 1821 after competition from British suppliers drove him out of business.

Following the death of Joseph Frederick Wallet Des Barres in October 1824, his family commissioned the younger brother of quarry-owner John Seaman, Amos Seaman, to collect on all outstanding rent from the quarries that Des Barres had leased on his land. Seaman and a business partner, William Fowler, took over the management and leasing of quarries in the area on behalf of the Des Barres family until 1834, when they purchased the land. In the time that Seaman owned the land quarries began to use "Joggins boats" to transport grindstone, which had been adapted from those used at the local fishery. As grindstone was quarried in parts of the coast that would be covered by water at high tide, the boats would come onto shore at low tide, be loaded as the miners worked, and then were sent off at high tide to deposit the stone elsewhere. As this kind of procedure could only safely be practiced in the summer there were no permanent bunkhouses set up for workers; instead, workers at South Joggins would establish seasonal camps at the top of the cliffs to be disassembled when the work dried up.

General Mining Association

The General Mining Association (GMA)[4] took over nearly all Nova Scotian mining operations in 1827. In 1825, the Duke of York had been deeply in debt to Rundell, Bridge & Co. when the firm learned of the 1788 lease that would have granted him mineral rights to all of Nova Scotia. A mining engineer was sent by Rundell, Bridge & Co. to scout Nova Scotia for copper, and while little of it was found the engineer reported that the colony was rich in coal. At the firm's insistence, the 1788 lease was rewritten to include coal and approved by King George IV. According to the new terms, this granted the Duke mining rights to the following for the next sixty years:

...gold and silver, coal, iron, stone, lime-stone, slate-stone, slate-rock, tin, copper, lead and all other mines, minerals and ores and all beds and seams of gold, silver, coal, iron, stone, lime-stone, slate-stone, slate-rock, tin, clay, copper, lead and ores of every kind and description belonging to his Majesty within the Province of Nova Scotia...[4]

Once the lease was issued, the Duke subletted it to Rundell, Bridge & Co. in exchange for 25% of all profits they generated off the minerals it covered. Rundell, Bridge & Co. founded a new firm, the General Mining Company, which would manage their Nova Scotian properties from London. Taking advantage of the region's natural resources, particularly coal, was imperative to the growth of British North America: fuel was hard to come by, the anthracite mined in the Coal Region of Pennsylvania being difficult to use and bituminous coal from the Appalachian Mountains proving costly to transport. The Association focused initially on deposits in Pictou and Sydney, where they were able to buy leases on preexisting mines and take advantage of infrastructure that was already in place. After acquiring the rights to Cape Breton (which had to be negotiated for separately) the GMA had established a monopoly over all the mines in Nova Scotia, and the Nova Scotia House of Assembly discouraged competition by refusing to grant leases to new mines even if doing so would not violate the terms of the Duke of York's lease. Though Des Barres's land claim had expired after his death, the GMA did not immediately make an attempt to establish themselves at Joggins, and actively discouraged anyone else from mining the Joggins Formation. Despite their urgings, small groups of Cornish settlers continued mining exposed coal veins in the area. By 1836 an illegal mine had sprung up around the King's Vein, accessed through an adit dug into the cliff wall where an outcropping had once been apparent.

Abraham Gesner returned to Nova Scotia in 1844 to petition the House of Assembly for the rights to mine at Joggins, as he felt the coal reserves had gone unused for too long and a shortage of firewood in Cumberland County provided ample opportunity for a new source of fuel. The colonial government, which had previously protected the General Mining Association from any threat of competition, had begun to change its stance on the GMA's monopoly: it was coming to light that the firm was offering discounts to American buyers but not Nova Scotians, and an 1842 report commissioned by Lieutenant Governor Lucius Cary suggested the GMA was poorly managing the Albion Mine in Pictou. The government decided to approve Gesner's request. To preserve their dominance in the colony, the GMA subleased a tract of land near the community of Joggins Mines (present-day Joggins) and opened the Joggins Mine in 1847. Joggins Mine was a shaft mine roughly 30 m (98.4 ft) deep,[5] accessing the King's Vein from above and using a horse gin to raise the coal to the surface, where it was loaded onto a narrow-gauge railway and transported to a pier near Bell's Brook to be loaded onto ships. The GMA hired Joseph Smith, manager of their Pictou mine, to oversee its early operations. Much of the coal mined at Joggins Mine was sold to buyers in Saint John, New Brunswick. Joggins Mine cost £16,000 to build, and after the initial start up costs were covered the GMA invested minimally in the site.

The General Mining Association lost many of its claims in 1858, but retained the right to mine from the Joggins Formation. By 1866, the Joggins Mine was producing an average of 8,478 chaldrons of coal per year, making it the least productive of any GMA mine in Nova Scotia. However, the Joggins Mine required only 9 horsepower of steam to operate normally and thus produced 943 chaldrons for each unit of horsepower expended, far more efficient than any other owned by the GMA.[4] In 1866 the company opened a new drift mine at Joggins: the New Mine. The New Mine harvested coal from the Dirty Seam and Fundy Seam (then known as the "hard scrabble seam"). Dendrochronological studies done on wood recovered from the site suggest that miners reused materials from earlier structures to construct the New Mine, as the lumber was determined to have been cut as early as 1849. Like earlier operations at Joggins, the New Mine was entered by an adit and coal was stored on-site until it could be transported to a wharf and loaded onto ships.

The New Mine was abandoned by the General Mining Association in 1871 and the land it was situated on was sold to the newly founded Joggins Coal Mining Company (JCMC), who opened a new mine to harvest the Fundy and Dirty Seams in 1872. Unlike the GMA, the JCMC used a slope mine tunnel that inclined down 82.3 m (270 ft) into the ground and was 121.9 m (400 ft) long. While the primary and transport tunnels were new, the latter intersected with those of the GMA's New Mine. The JCMC had been founded amid a coal boom and profited greatly from the Intercolonial Railway, which passed through nearby Maccan and allowed Joggins coal to be sold easily to buyers in Saint John and Halifax, where it was used to fuel trains and hearths. On 22 June 1877 the Great Saint John Fire destroyed 1,612 structures and killed 19 people, ravaging the city's coal market and heavily impacting the JCMC's sales. The JCMC closed their mine later that year.

The Springhill and Parrsboro Coal and Rail Company, founded in 1872, acquired the General Mining Association's Cumberland County mineral rights in 1879,[6] ending the GMA's involvement in Joggins. Around this time control of the Joggins mining economy shifted from merchants in Saint John to financiers in Montreal, and in 1884 the Springhill and Parrsboro Coal and Rail Company sold out to the Cumberland Railway and Coal Company. The Joggins Railway was completed in 1887, connecting the town of Joggins directly to the rest of the Intercolonial Railway and further reducing the cost of transporting coal. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, miners in Cumberland County - including Joggins Mine - had a tradition of stopping work immediately after a death occurred in the mine and not recommencing until the killed worker's funeral, but by 1887 this was no longer the case and labourers were forced to mine even on the day of the funeral.[7]

Early geological research

Harvard University geologists Charles Thomas Jackson and Francis Alger published the first scientific notes regarding Joggins in 1828, followed the next year by Richard Smith and Richard Brown of the General Mining Association. Smith and Brown's report contained the first stratigraphic reconstruction of the Joggins Cliffs as well as the first mention of fossil trees at the site,[8] which they believed had been fossilized when the forest they belonged to flooded and became covered in sediment.

Geologists Abraham Pineo Gesner and Charles Lyell arrived at Joggins on 28 July 1842. Gesner had earlier explored the cliffs in 1836, where he described them as "the place where the delicate herbage of a former world is now transmuted in stone".[3] Lyell at this time was famous for publishing his Principles of Geology (1830-1833), which popularized uniformitarianism, and was persuaded to visit Joggins after reading Gesner's 1836 observations of the cliffs and 1829 report by Brown and Smith. Based on these earlier studies, Lyell believed the cliffs represented multiple forests that had grown on the same site, being flooded and buried in succession many times, and that their fossilization was related to the formation of coal. As expected, Lyell and Gesner witnessed many fossil trees at Joggins, which greatly inspired Lyell. On this expedition, Gesner noted the ruins of an abandoned fort which had partly collapsed with the eroding of the cliffside, a remnant of Major Henry Cope's attempt to restart his mining operation in 1733.[2] The geologists wrapped up their brief expedition on 30 July 1842. Their relationship deteriorated soon afterward as the two did not agree on the ages of strata in Nova Scotia, Lyell believing the Windsor Group was younger than the province's Coal Measures and Gesner believing the opposite to be true. Gesner did not return to Joggins after this falling out, and opened Canada's first public museum - the Museum of Natural History - in Saint John, New Brunswick later that year.

1843 survey

The Joggins Formation was first surveyed by William Edmond Logan.[9] Logan's theories of in situ coal formation at the Glamorganshire Coalfield in Wales had been published in 1840, challenging the accepted "drift theory". Logan had earlier completed two private surveys of the Nova Scotian coast in 1840 and 1841, both times searching for evidence the in situ theory applied to coal deposits other than the one he'd studied. The British government approved the creation of a survey to search for coal in the Province of Canada in September 1841. Logan and his supporters - including Director of the British Geological Survey Sir Henry De la Beche and early palaeontologist William Buckland - lobbied for him to lead the survey, and on 9 April 1842 he was named head of the Geological Survey of Canada.

Logan's work at Joggins was the first assignment he undertook for the survey and took place over the course of five days, from 6 June to 10 June 1843. Joggins was of particular interest to Logan after reading the work of Charles Lyell, who had recently published his discoveries of fossil trees embedded in situ in the cliffs. The survey was scheduled to begin immediately after Logan's arrival in Minudie, Nova Scotia on 4 June 1843, but was delayed by heavy rainfall. Logan's survey of the "Joggins section" began at Mill Cove, and 8,400 feet of strata were measured on the first two days of the expedition. It was on the second day, 7 June, that Logan first encountered the coal-bearing Joggins Formation, which slowed his progress along the coast. The third day of the survey, 8 June, was devoted to studying the area between where he'd left off the previous day and Ragged Reef Point, a 3,900 ft-long stretch that would come to include the fossil-rich Division 4. On his final two days studying the Joggins section, Logan scouted the area from Ragged Reef Point to just beyond West Ragged Reef Point, where he concluded his research. After completing this brief survey, Logan left Joggins on 12 June to continue studying the known coal deposits of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick before moving on the Gaspé Peninsula. Though Logan's survey was included as a report in the proceedings of the British government it fell into obscurity; years later, in a letter to Henry De la Beche, he would remark "who the devil ever reads a report".[9]

1852 survey

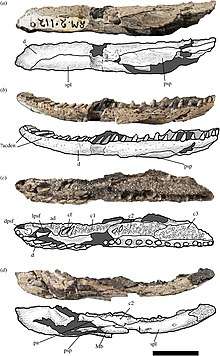

On Charles Lyell's third trip to the Americas, he made plans to visit Joggins a second time. He joined up with John William Dawson in Halifax and the two arrived at Joggins on 12 September 1852. The two measured 859.28 m (2819 ft, 2 in)[9] of the cliffs, unaware that William Logan had already conducted a survey nine years earlier. While examining the cliffs, Lyell and Dawson discovered the fossil remains of a Dendrerpeton inside a fossil tree at Coal Mine Point.[8][10] The tree had fallen from the cliffs, and has previously been entombed in Coal 15. Lyell and Dawson also discovered fossilized millipedes in the tree trunks, and fossils of the land snail Dendropupa. Among other things, the evidence of "reptile" (the distinction between reptiles and amphibians had yet to be made clear in 1852) fossils in strata of such age would disprove the argument made by proponents of catastrophism that Palaeozoic fishes had lost global dominance to the reptiles amid a worldwide catastrophe at the beginning of the Mesozoic era.

Following the expedition, Charles Lyell took the fossils to be studied in Boston, where they were studied by Louis Agassiz and Jeffries Wyman at Harvard University. Agassiz first dismissed the remains as belonging to a coelacanth and Wyman believed they were those of a marine reptile related to Proteus anguinus, but after working the fossils out of the stone they'd been recovered in the scientists confirmed that the fossils represented bones from two reptiles: seven vertebrae and an ilium. At the time, only four tetrapod specimens had been recovered from coal formations around the world, meaning the eight bones recovered by Lyell and Dawson represented one-third of all Carboniferous tetrapod fossils. Lyell communicated this discovery to John W. Dawson in a letter on 6 November 1852, and publicly announced them in a series of lectures - the "Lowell lectures" - delivered at the Lowell Institute several weeks later. It was around this time that Lyell and Dawson became aware of William Logan's 1843 survey of the Joggins Formation, and on 16 December 1852 Lyell sent a request to Logan for a copy of his work to compare against their own. Logan insisted in a letter dated 10 January 1853 that he had already sent Lyell a copy years earlier when his report was first issued, illustrating the ambivalence the researchers had towards each other. Lyell and Dawson's discovery was relayed to the Geological Society in London on 19 January 1853, but unbeknownst to either of them a postscript had been added to their paper by Richard Owen, who had described and named the fossil as Dendrerpeton acadianum. In 1855, Dawson collected his and Lyell's research on Joggins into Acadian Geology, a text that drew serious interest from geologists across England and the United States.

1855 also marked the only trip that Othniel Charles Marsh made to Joggins. Marsh had only recently begun to study at Yale University and was likely drawn to Joggins by the abundance of fossils described by Charles Lyell and John W. Dawson. Marsh returned to Yale with two vertebrae, which he described in 1862 as belonging to the marine reptile Eosaurus acadianus. Six years later Dawson commented that Marsh's description of Eosaurus closely resembled that of Ichthyosaurus, which at the time had only been found in European limestone such as the quarries of Lyme Regis, England. Vertebrate palaeontologists Donald Baird, Alfred Romer, and Robert L. Carroll have suggested that Marsh's Eosaurus actually represents fossils of Ichthyosaurus which Marsh purchased off someone who claimed they had been found at Joggins and passed the find off as his own discovery.[3]

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin's seminal text On the Origin of Species was published on 24 November 1859. Charles Lyell had greatly influenced Darwin, as Robert FitzRoy gifted him a copy of Lyell's Principle of Geology before Darwin embarked on his five-year voyage aboard HMS Beagle and Lyell wrote personally to Darwin in April 1843 to announce his findings on the expedition with Abraham Gesner. Darwin built a considerable amount of his theory regarding natural selection and evolution on Lyell's 1852 study of the Joggins Formation, noting that the incompleteness of the fossil record at Joggins was responsible for gaps in Darwin's theory and saying this incompleteness had contributed to a misconception of "abrupt, though perhaps very slight, changes of form".[3] Lyell helped publish Darwin's theories, but did not support them as natural selection conflicted with his religious beliefs. In 1863, John W. Dawson published Air-Breathers of the Coal Period, both a catalogue of all known species from the Joggins Formation at the time and a response to On the Origin of Species. Dawson argued that the presence of fossils like Dedropupa (which he'd first reported on in 1860) disproved Darwin's theory, as this land snail was virtually identical to its modern counterparts, and thus the body plan of snails had not changed in 300 million years. Dawson's disbelief in natural selection was not based in religious concerns, as he did believe in deep time and the notion that higher forms of life had appeared progressively and at different periods in Earth's history; in 1865 he would argue that Eozoon canadense represented the earliest form of life. Samuel Wilberforce had also referenced Dedropupa in his 1860 criticism of On the Origin of Species, calling it the "miserable little dendropupa".[11]

Charles Darwin also followed Charles Lyell in trying to explain the origins of the Joggins coal beds. In 1847 he suggested to Joseph Dalton Hooker that the trees at Joggins may have grown underwater, at depths between 5 and 100 fathoms. Hooker dismissed this idea in a letter to Darwin on 6 May 1847, a rejection Darwin described as a "savage onslaught".[3] William Logan's observations on Stigmaria had been published in 1841, where he noted that the fossils represented roots that had grown, died, and been preserved in the same place they had been discovered. While it was widely accepted that coal had once been plant material, Logan's notes on Stigmaria represented the first compelling evidence that coal was the product of terrestrial plants. Darwin made a major breakthrough in 1860 when John W. Dawson published his paper reporting the discovery of Dendropupa, a non-aquatic animal, in the trunk of a fossilized trees at Joggins. This find convinced Darwin that the trees had in fact grown on land and coal must have a terrestrial origin, existing first as peat.

John W. Dawson's later work

John W. Dawson returned to Joggins in the summer of 1853 without Charles Lyell, who had been hired to work for the 1853 World's Fair in New York City. Dawson continued to investigate the Joggins Formation alone, and on 2 November 1853 sent his completed survey to Lyell. Dawson claimed that his and Lyell's findings matched those made by William Logan, and by 1855 Dawson no longer used his own survey and began to rely only on Logan's for reference. In a 2005 review of their respective surveys, it was determined that Dawson and Lyell's work was more accurate than Logan's.[9] Hylonomus lyelli was discovered at the Joggins Cliffs by Dawson and formally described in 1859. Named in honour of his colleague, Charles Lyell, the species would later be recognized as the oldest known reptile and be made the provincial fossil of Nova Scotia. A fossil trackway Dawson discovered in 1866 was at one point believed to have been made by the largest known invertebrate Arthropleura, but Dawson eventually found the trackway distinct enough to be assigned to its own species: Diplichnites aenigma.[12] Dawson would devote much of his career to studying the Joggins Formation and again returned in 1877, undertaking an expedition funded by the Royal Society to search for more specimens embedded in the fossil trees. Explosives were detonated at Coal Mine Point, exposing twenty-five lycopsid trees; of these, fifteen contained vertebrate fossils representing over one hundred specimens, the largest single collection of Palaeozoic tetrapods ever found.[3] Dawson and Lyell would come up with many theories over the years to explain why so many animals would assemble there. The first suggestion had been that the creatures had been denning, but it was also suggested that they had died elsewhere and were washed into the trunks by water. Ultimately, Dawson would come to believe that the animals had fallen into the trunk and died there, unable to escape.

In studying the Joggins Formation, John W. Dawson collaborated not just with Charles Lyell, but also Augustus Addison Gould, Joseph Leidy, John William Salter, and Samuel Hubbard Scudder. Dawson's work at Joggins spanned a total of 44 years, his last update to Acadian Geology being published in 1891.

Early-20th century

The son of a mining engineer, Hugh Fletcher devoted his career as a geologist to surveying Nova Scotia on behalf of the Geological Survey of Canada. Fletcher's work began in 1875 and ended abruptly in 1909 when, on a mission to conduct a full survey of Nova Scotia, Fletcher fell ill with pneumonia studying the Joggins Formation and died. Reginald Walter Brock, a colleague of Fletcher and also of John W. Dawson, eulogized Fletcher by saying "he died, as he would have chosen, in harness, and amid the hills of his well-loved Nova Scotia".[13]

Based on bivalve fossils recovered from the Joggins Formation, Joseph Frederick Whiteaves described Asthenodonta in 1893, but the genus was redescribed later that year by Thomas Chesmer Weston, who renamed it Archanodon. George Frederick Matthew, a pioneer in the field of ichnology also took an interest in Joggins and published his observations on tetrapod trackways recovered from the site in 1903.[14]

Walter A. Bell began researching the Joggins Formation in 1911, almost immediately after his graduation from Yale University. Bell was one of Canada's delegates at International Geological Congress's twelfth meeting in 1913, and accompanied the other delegates on a tour and dinner at the Joggins Cliffs that year. In 1914, Bell conducted the first detailed study of macrofloral fossils across Nova Scotia's Carboniferous formations,[15] including the Mabou Group and Cumberland Group; as part of this study Bell assigned Divisions III, IV, and V (and part of Division II) to the "Joggins Formation", the first use of the name.[11] Following the outbreak of World War I, Bell was conscripted to fight for Canada in Europe, serving from 1916 to 1919. Following the end of his military service, he studied fossils in Europe for several months before returning to Yale. Bell finally returned to Nova Scotia in 1926, and his research into Carboniferous plants would reveal that many of the species found in Atlantic Canada were also present in Western European deposits, providing evidence for the theory of continental drift. In 1944 Bell reconsidered his classification of the Joggins Formation, reclassifying it as the "Joggins member" of an undivided Cumberland Group. Bell continued to study the Joggins Formation until his death in 1969.

Holdfast Lodge

The Joggins Mine continued to produce coal throughout the First World War and even amid the great scientific interest surrounding the Joggins Formation. Production at the Joggins Mine peaked in 1916 when the mine generated 201,000 tons of coal over the course of the year.[6] The amount of workers in Joggins steadily increased with production, but as Nova Scotia deindustrialised and other mines shut down the percentage of Cumberland County miners employed at Joggins increased from 21% in the 1880s to 25% in the 1900s and 43% in the 1910s.[7]

The Provincial Workmen's Association (PWA) established an early foothold in Joggins, first with Brunswick Lodge and later with Holdfast Lodge. Brunswick Lodge was the first to represent Joggins Mine workers. In 1884 the union attempted to negotiate with their employer at the time, prompting the manager - known in contemporary accounts as "Mr. B." - to remove his gloves and threaten to beat every worker. The company withdrew from negotiations and offered workers $10.00 each to abandon the union and come back to work. The strike went on, and when one miner attempted to retrieve his wages from Mr. B. the manager threw a piece of cast iron at him. The miner retaliated by throwing the iron back at Mr. B., striking him in the head but causing no severe injuries. Despite the clear belligerence between the company and the workers, strikers eventually began to cross the picket line and Brunswick Lodge dissolved that year.

By 1895, Holdfast Lodge represented 20% of Joggins Mine's workers, the largest union in mainland Nova Scotia at the time.[16] The politics of Holdfast Lodge were considered radical even by the standards of other Provincial Miner Workers chapters in Nova Scotia. 15 of the 19 PMW strikes that were held in the 1890s happened in Cumberland County, and Holdfast Lodge organized three in 1895 alone. Robert Drummond, Grand Secretary of the PMW, was particularly annoyed by their negotiations and tactics, their membership being largely uneducated and militant. Amid the threat of a wage reduction in the winter of 1895–96, Holdfast Lodge ordered all Joggins Mine workers to strike despite being ordered by Drummond not to, and in mid-March 1896 an estimated 200 members of Holdfast Lodge barricaded themselves inside the local PWA meeting hall to resist arrest, arming themselves with bricks, a number of assorted small arms, and 27 rifles. Nonetheless, Premier William Stevens Fielding engaged with Holdfast Lodge in order to build a loyal and powerful voter base. Fielding was leader of the Anti-Confederation Party and had been elected on a promise to remove Nova Scotia from Confederation, and when he failed to fulfill this promise he refocused his efforts on expanding the province's coal industry instead. One of Fielding's unconventional tactics involved working with the PWA to improve workers' access to education. The federal Liberal Party also campaigned hard for the PWA, as Cumberland had long been a Conservative Party stronghold: Cumberland had only ever been represented by Conservative Members of Parliament since Confederation and in nine elections had supported Charles Tupper, who was leading the Conservatives in 1896. Support from Holdfast Lodge managed to turn Cumberland in favour of the Liberals, and Hance James Logan was elected to the Parliament on 23 June 1896.

The PWA succeeded in part because of their support for the community's funerary traditions, shutting down facilities like the Joggins Mine following a death and not returning to work until the deceased worker was put to rest. Such elaborate traditions had once been commonplace, but were mostly abandoned by the turn of the century until revived with the protection offered by unions. In 1898 the manager of Joggins Mine insisted the workers send a delegation to the funeral rather than shut down the mine for a day to attend; this request was ignored. In 1906, a funeral procession consisting of all the miners in Joggins marched from town to the Maccan River Bridge.

The PWA came into conflict not just with mine managers, but also with the United Mine Workers, which had been founded in the United States in 1890. The PWA and the provincial United Mine Workers organization united in 1917 to form the Amalgamated Mine Workers of Nova Scotia, which was assimilated into the UMW in 1918.

Child labour

| Year | Child labourers | Percentage of

coal mine workforce[17] |

|---|---|---|

| 1874 | 555 | 14.1 |

| 1876 | 565 | 16.1 |

| 1878 | 510 | 16.9 |

| 1880 | 519 | 17.1 |

| 1882 | 627 | 18.1 |

| 1884 | 768 | 16.8 |

| 1886 | 722 | 16.5 |

| 1888 | 740 | 17.2 |

| 1890 | 1,102 | 21.5 |

| 1892 | 882 | 15.6 |

| 1894 | 844 | 14.5 |

| 1896 | 699 | 12.3 |

| 1898 | 686 | 13.4 |

| 1900 | 735 | 13.4 |

| 1902 | 792 | 10.4 |

| 1904 | 877 | 8.3 |

| 1906 | 826 | 7.7 |

| 1908 | 921 | 7.6 |

| 1910 | 1,063 | 8.8 |

| 1912 | 922 | 7.4 |

| 1914 | 831 | 6.1 |

As was the case with many of Nova Scotia's mining operations, the coal mines at Joggins employed child labour when possible. Following the deaths of 70 miners and a single boy in the Drummond Mine explosion on 13 May 1873 in Westville, miners in Joggins adopted a rule of allowing children working in the mines to be the first to leave at the end of the day.[18] While children were paid less than their adult colleagues, their income was indispensable to mining families which were typically impoverished. Class disparity became obvious with the advent of education as a status symbol, poor children often abandoning school early in life to work the mines.

In August 1905 a number of child miners at Joggins left work on a recreational strike when they left work to play a game of baseball.

Ideas surrounding childhood began to shift in the mid-19th century. The Mines Act of 1873 prohibited anyone under the age of 10 from working in any Nova Scotian mine, and in 1891 the minimum age of miners was raised to 12. In 1908 legislation banned the employment of any child miner who had not completed a grade seven education. Nova Scotia adopted the Free Schools Act in 1864 to provide public funding for schools which agreed to follow provincial standards of education, and in 1883 public school boards were given the right to fine parents of children aged 7-12 if their child did not attend at least 80 days of school per year. Nova Scotia finally enforced province-wide compulsory attendance for children aged 7–14 in 1921. In 1923 the Mines Act was amended to ban children from coal mines altogether, raising the school-leaving age to 16 and prohibiting anyone below that age from working in a mine.[17]

Don Reid and the Joggins Fossil Centre

Donald R. "Don" Reid (1922-2016)[19] was born on 29 May 1922 in Joggins, Nova Scotia. Reid's family was involved in the Joggins Mine, around which Joggins's economy was based, and as a teenager he was forced to leave school when his father sustained an injury in the mine and could no longer work. During this time Reid developed an interest in the Joggins Formation's abundance of fossils, collecting and studying them despite having no formal training as a palaeontologist.

Don Reid was not the only person taking an interest in the site, and in 1972 a 1.6 km (1 mi) section of the Joggins Cliffs were protected under the Historical Objects Protection Act, which was repealed and replaced with the Special Places’ Protection Act in 1980 and prohibited fossil collecting from Joggins or anywhere else in Nova Scotia without a permit. Though the risk of fossil poaching was not high in Joggins, the legislation ensured Reid remained one of only a handful of people authorized to research the cliffs. The Reid family opened a visitor centre on their property in 1989 to exhibit the vast collection, spurring the creation of the Joggins Fossil Centre at Coal Mine Point in Spring 1993.[20] Reid and his assistant often gave personal tours of the Joggins Cliffs, and the Reid family claims that the Joggins Fossil Centre hosted visitors from more than 44 countries. Reid acquired the nickname "Keeper of the Cliffs" from the Joggins community during this period. Reid was instrumental in having UNESCO declare the Joggins Fossil Cliffs a World Heritage Site, which occurred on 7 July 2008.[1][5] Reid provided the heritage site staff with a significant number of fossils from his own collection, and continued to hike along the Joggins Cliffs up until his death on 17 November 2016.[21]

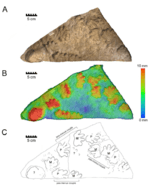

A number of institutions and societies honoured Don Reid for his contributions to palaeontology, particularly in the latter years of his life. In 2013, the Atlantic Geoscience Society granted Reid the Laing Ferguson Distinguished Service Award, and in 2016 Reid was inducted into the Order of Nova Scotia. In 2015, researchers announced that a new ichnofossil - a tetrapod trackway found in several formations of the Cumberland Group including the Joggins Formation - would be named in honour of Reid when the species was formally described. The trackway consists of footprints 10 cm (3.9 in) wide, and likely represent the Joggins Formation's largest tetrapod and top predator (possibly Baphetes).[22]

Recent history

The Joggins Formation, which had been treated only as a member of the Cumberland Group since 1944, was formally reclassified as its own formation in 1991. The new classification used the measurements of William Logan's 1843 survey and contained Divisions IV and V, as well as the base of Division III. While the decision to define this section as a distinct formation has been upheld in later studies, the exact boundaries of the Joggins Formation have been debated. In 2005, the Joggins Formation was reformulated to consist of only Division IV and the limestone base of Division III.

A bronze plaque was erected in Joggins in May 1992 to commemorate the 150-year anniversary of the Geological Survey of Canada's inception. The plaque is dedicated to the work of Sir William Logan.[20]

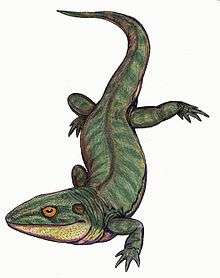

Hylonomus, the earliest-known amniote and one of the Joggins Formation's most famous genera, was featured on an official Canada Post stamp in 1992, and was made the official fossil of Nova Scotia in 2002.[23]

An international team of geologists remeasured the Joggins Formation in 2005, the first time such a procedure had been done since Charles Lyell and John W. Dawson's survey in 1853.[11]

To celebrate ten years as a UNESCO heritage site, the Joggins Fossil Institute hosted the first Joggins Research Symposium on 22 September 2018.[12] A number of improvements were suggested to improve the site for research and educational purposes, including the construction of a storage facility for fossil trees recovered from the cliffs which could bear tetrapod fossils, the development of machine learning software to better identify fossils at the site, and revision of the Special Places Protection Act.

Geology

The Joggins Formation overlies the Little River and Grand Anse Formations, and underlies the Polly Brook Formation. It is part of the Cumberland Group of geological formations, which extends from the early Namurian stage to the Westphalian stage of the Carboniferous period.[11] The deposit represents a time when the region was dominated by a tropical rainforest, and consists of an enormous quantity of sedimentary rock. This material was deposited by rivers and flood water moving northwards, leaving behind sediment that subsided between two fault blocks: the Cobequid Mountains and Caledonia Mountain (present-day Caledonia Mountain, New Brunswick), both of which were active in the Carboniferous.[22] Halokinesis along basement faults sped up the process of subsidence by removing subsurface salt from the ground. The high occurrence of flooding events in the Joggins Formation suggests that the territory rapidly subsided into the Cumberland Basin.[11] Sand from a crevasse splay may also have been responsible for intermittently burying the region and preserving its biota as fossils.

The cliffs of the Joggins Section have eroded rapidly since the initial surveys were conducted, with estimates ranging as much as a 50 m (164 ft) change in the 152-year period between 1853 and 2005.[9] John W. Dawson estimated in 1882 that, based on four decades of observation, the cliffs erode at a rate of roughly 19 cm (7.5 ft) per year.[5] Estimates about how much of the Joggins Formation is actually exposed along the Joggins Cliffs range from 915.5 m (3,003.6 ft) to 2.8 km (1.7 mi).[12][11]

Grindstone quarries along the Joggins Section were once responsible for producing Nova Scotia blue-grit, a sandstone that was in high demand in the early-19th century.

Subdivision

The Joggins section consists of eight divisions of exposed strata along the southern shore of Chignecto Bay. While the Joggins Cliffs extend roughly 20 km from Minudie to Shulie, Nova Scotia,[2] the Joggins Formation is much shorter: in older accounts it represents only 2.8 km (1.7 mi) of this stretch, but more recent measurements found it to be 915.5 m (3,003.6 ft) long and extend 40 km (25.9 mi) inland.[11] According to the 1843 survey by William Logan, the Joggins Section is about 4.44 km (14,570 ft, 11 in) long;[9] the exact measurements of each division varied, as Logan used paced measurements to calculate distances. The divisions are numbered from top to bottom, with Division 1 containing the youngest strata and Division 8 containing the oldest.

Division IV

Division IV forms the basis of the Joggins Formation, with only a small amount of overlying strata being considered part of the broader formation. Measured originally by William Edmond Logan in 1843, Division IV consists of a 773.9 m (2,539 ft 1 in) stretch of coal-bearing strata along the Joggins Cliffs. Division IV has an aggregate coal thickness of 11.5 m (37 ft 9.5 in), contrasting with 7.1 m (23 ft 3 in) of limestone.[11] The base of the formation is located at Coal Group 45, at the Lower Cove of the Joggins Cliffs, and consists of seatearth, red shale, and sandstone. The roof of the division lies just above Coal Group 1, where 30.5 cm (1 ft) of coal is overlayed by 1.2 m (4 ft) of limestone.

Division IV is divided into 14 cycles, each representing successive flooding events which deposited biotic material into what is now the Joggins Formation. Each cycle is separated by deposits of limestone, shale, or coal; for instance, the Joggins Seam (formerly "the King's Vein") divides Cycle 12 and Cycle 13 of the Joggins Formation. Cycle 10 is 158 m (518.4 ft) thick, and stretches from the Queen's Vein to Coal Mine Point. Some coal seams are located within cycles rather than at the borders, such as the Fundy Seam which is located in Cycle 6. Cycle 5 represents the longest period of sediment accumulation in the Joggins Formation, and is more than 200 m (656.2 ft) long.

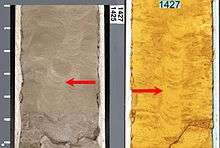

Other minerals found in Division IV include mudstone (red and grey), sandstone, shale (grey, red, red-grey, and chocolate), and minor conglomerates. Shale constitutes 34% of Division IV, aggregating 364 m (1,194.2 ft) of material. An ochre-coloured section of the Joggins Cliffs surrounding the Fundy Seam is not a natural phenomenon, but instead caused by iron-rich acids leaking out of the mine there.[8]

Other divisions

Division II contains predominately red sandstone and mudstone. Division II has not been considered part of the Joggins Formation since 1944.

Division III contains fewer coal groups and more red sandstone than Division IV, which it overlays, and no limestone. In total, Division III includes 22 coal seams with an aggregate thickness of 1.7 m (5 ft 5 in). The limestone base of Division III is considered part of the Joggins Formation, but the rest is not.

Composed largely of grey sandstone, red sandstone, and red mudstone, Division V also bears some green shale and limestone. Division V contains no coal groups, and stretches 634.6 m (2,082 ft) from Lower Cove to South Reef. Division V was considered to be part of the Joggins Formation when the formation was defined in 1914 and 1991, but has been considered distinct since 2005.

Coal

Coal is abundant in the Joggins Formation and surrounding Joggins Cliffs, and was mined for centuries. There are 45 coal groups located in the formation. Coal Group 45 lies at the base of the Joggins Formation, and though the section assigned to this group stretches 3.1 m (10 ft 2 in) from start to finish, only 7.6 cm (3 in) of this actually represents basal coal.

Two of the most heavily mined deposits of coal - the Fundy Seam and Dirty Seam - are part of the Joggins Formation. The Fundy Seam is 0.85 m (2.8 ft) thick, and is made of bituminous coal, while the Dirty Seam is 1.5 m (4.9 ft) thick and made of clastic-rich coal; they are present at 420 m (1,378 ft) and 428 m (1,404.2 ft) above the formation's stratigraphic base.[5] Other major seams in the Joggins Formation include the Joggins Seam (formerly the "King's Vein" and "Coal 7"), Queen's Seam ("Coal 8"), Forty Brine Seam ("Coal 20"), and Kimberly Seam ("Coal 14"). The majority of the Joggins Formation lies between Coal 34 and Coal 45, where coal is abundant.

Coal harvested from Joggins was described as being "of inferior quality abounding with sulphur" in 1787.[2]

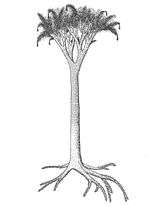

Fossil trees

The Joggins Formation is of particular interest to geologists for its saturation with fossilized plants, one of the best-preserved coal forests known to science. Though often referred to as "trees", the large plants that made up the Joggins Formation's forest were lycopsid, which today only exist as club mosses. In the Carboniferous, lycopsids could grow as tall as 30 m (98.4 ft) with trunks nearly 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter and came to resemble modern trees through convergent evolution. As trees they do not constitute a taxonomic group, Carboniferous lycopsids are as much trees as any extant species despite being only distantly related. When the region was covered with marshland lycopsid would put down roots on the solid ground of newly made alluvial plains where young individuals faced little competition but were at risk of flooding. If the river banks burst before the forest floor had accumulated a significant amount of peat the lycopsids would be swamped by sand carried overland in a crevasse splay, burying the trunk and killing the tree as well as any other living thing in or around it. One such event of this kind buried the Fundy forest, a section of the Joggins Formation located in Cycle 6, around 419 m (1,374.7 ft) from the base of the formation.[11] Once dead, the section of trunk not submerged in sand would rot and decay while the section buried underground had a chance at fossilization. The Joggins Formation is famous for these tree trunks, as while they are valuable in their own right they also protected the carcasses of many animals which fossilized as well. It is unknown how creatures like Hylerpeton or Dendropupa came to be trapped in the trunks, but it has been suggested they were either using the trees as dens, or they fell into the hollow trunks as the trees were rotting and were buried when sediment collapsed into the interior.[3] One trunk recovered from the Joggins Formation contained thirteen separate vertebrate specimens. A total of eleven tetrapod species have been discovered within fossil tree trunks at Joggins. While greater quantities of sand would preserve taller trunks, the higher mass would crush the tree's roots, which is why Stigmaria fossils are only found around shorter trunks. Scour hollows up to 1 m (3.3 ft) deep and 4 m (13.1 ft) long surround some well-preserved trunks.[8]

Though lycopsid trunks are among the best known plants from the Joggins Formation, the fern genus Calamites represents more fossils than almost any other organism preserved in the Joggins Cliffs. Resembling the modern-day horsetails they are related to, the stems Calamites plants typically grew to be 10-12 cm (3.9-4.7 in) in diameter and more than 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall, though one specimen was found to be 90 cm (35.4 in) thick and nearly 3 m (9.8 ft) tall.[20] These ferns grew mostly upright, spacing 15-30 cm (5.9-11.8 in) apart from each other and forming a thick forest floor. Usually, only the lower portion of Calamites plants was preserved, but their mostly-intact fossils suggest they were buried very quickly, likely by the same methods which preserved lycopsid trunks. Despite the comparative notoriety of Joggins's fossil trees and Hylonomus, no specimens of Hylonomus have ever been recovered from inside a tree trunk; this likely due to the incompleteness of the fossil record.[8]

Fossil trees are most often discovered in intervals between the Coal 29 (the Fundy Seam) and Coal 35.[8]

Palaeobiology

Dozens of tetrapod, invertebrate, and plant fossils have been recovered from the Joggins Formation. A diverse array of ichnofossils have also been found at Joggins, including vertebrate trackways, invertebrate trace fossils, tunnel structures, rhizoliths, and possibly wood borings.[12]

Fish coprolites are abundant in the limestone of the Joggins Formation, averaging lengths of 2-3 cm (0.79-1.18 in).[12] Research into these coprolites suggests that carnivorous fishes were far more prevalent in the region than herbivorous ones. Bone fragments have been found in nearly every fish coprolite at Joggins, though none have ever been successfully matched to a vertebrate genus.

Hydrology

Palaeobotanical research at the Joggins Formation suggests vegetation played a vital role in maintaining the ecosystem's water balance and shaping the waterways of Palaeozoic Joggins. The deep roots of tree-like plants like lycopsids and calamitaceaens stabilized river banks and formed river bars. This behaviour is more common in younger deposits of the Joggins Formation than in older strata. Gymnosperm forests covered much of the alluvial plains and the basin-margin highlands and were occasionally devastated by forest fires, possibly a result of high atmospheric oxygen. Conditions in the wetlands resembled those of some modern waterways, as commented on by John William Dawson:

... these beds carry our thoughts back to a period when the district was covered by a strange and now extinct vegetation, and when its physical condition resembled that of the Great Dismal Swamp, the Everglades, or the Delta of the Mississippi.[8]

Rivers and streams up to 6 m (19.7 ft) wide irrigated the region's rainforests for millions of years. A channel preserved in Cycle 9, at 580 m (1,902.9 ft) from the formation's base, represents a narrow distributary which delivered water directly to the sea, while the sediments found at Coal Mine Point suggest a meandering river covered the site. Sediments preserved at the top of each cycle suggest that the area witnessed a long trend of minor flooding which preceded a heavy drowning event, the latter creating the boundaries between cycles. The area was located very close to the coast, the exact proximity changing with rises and falls in sea level. Though the tides had a great deal of influence on the waterways in the area, there are no tidal indicators recorded in the Joggins strata.

The "Hebert beds" are located in Cycle 5, roughly 270-274 m (886-899 ft) from the base of the Joggins Formation. While the name of this area is an informal designation, the Hebert beds are of great value to palaeontologists for the amount of fossils located at the site. It is believed that the Hebert beds once hosted deep watering holes, which sustained surrounding plants and animals during dry seasons and prolonged droughts. Fossils found at the Hebert beds include Archanodon and Dendropupa shells.

Animals

Amphibians

| Amphibians reported from the Joggins Formation[24][25] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

A. longidentatum |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

| ||

|

Archerpeton |

A. anthracos |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XII, coal-group 26 |

|

||

|

B. minor |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XII, coal-group 26 |

|

|||

|

D. acadianum |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

| ||

|

D. confusum |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XII, coal-group 26 | ||||

|

D. helogenes |

||||||

|

Dendrysekos[12] |

D. helogenes |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

||

|

H. dawsoni |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

|||

|

L. problematicum |

Coal Mine Point |

|

|

|||

|

indeterminate |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XII, coal-group 26 |

|

|||

|

Smilerpeton |

S. aciedentatum |

|

_BHL22917199.jpg) | |||

|

Steenerpeton[29] |

S. silvae |

|

||||

|

Trachystega[28] |

T. megalodon |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XII, coal-group 26 |

|

||

|

unidentified cochleosaurid |

indeterminate |

|||||

Annelids

| Annelids reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

S. carbonarius |

| |||||

Arthropods

| Arthropods reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

C. bairdiodes |

||||||

|

C. salteriana |

||||||

|

C. altilis |

||||||

|

C. elongata |

||||||

|

C. fabulina |

||||||

|

C. humilis |

||||||

|

C. pungens |

||||||

|

C. rankiniana |

||||||

|

C. secans |

||||||

|

Coryphomartus |

C. triangularis |

|||||

|

G. carbonarius |

||||||

|

Hilboldtina |

H. rugulosa |

|||||

|

Mazonia[30] |

M. acadica |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 | |||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

Pygocephalus |

P. dubius |

|||||

|

Velatomorpha |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

X. sigillariae |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 | ||||

|

unidentified eurypterid (possibly Hibbertopterus/Mycterops) |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

unidentified scorpion |

indeterminate |

|||||

Fish

| Fishes reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Ageleodus |

A. pectinatus |

| ||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

C. plicatus |

||||||

|

Ctenoptychius |

C. cristatus |

|||||

|

G. duplicatus |

| |||||

|

H. cf. corrugata |

||||||

|

H. cf. canadensis |

||||||

|

Helodus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

S. cristatus |

||||||

|

S. plicatus |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

unidentified acanthodian |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

unidentified cartilaginous fish |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

unidentified coelacanth |

indeterminate |

|

||||

|

unidentified crossopterygian (possibly Rhizodopsis/Strepsodus) |

indeterminate |

|||||

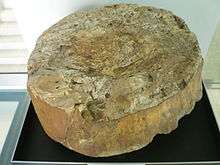

Molluscs

| Molluscs reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Archanodon |

A. westonis |

|||||

|

Curvirimula |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Dendropupa |

D. vetusta |

|||||

|

Naiadites |

N. carbonarius |

|||||

|

N. longus |

||||||

|

P. bigsbii |

_(14778882451).jpg) | |||||

|

Z. priscus |

||||||

Reptiles

| Reptiles reported from the Joggins Formation[24][25] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

H. latidens |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 | ||||

|

H. lyelli |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

| ||

Reptilomorphs

| Reptiliomorphs reported from the Joggins Formation[24][32] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

C. watsoni |

|

|||||

Synapsids

| Synapsids reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

A. platyris[29] |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

|||

|

Novascoticus |

N. multidens |

|||||

|

P. haplous |

||||||

Incertae sedis

| Animals placed incertae sedis reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Eosaurus |

E. acadiensis |

possibly Lyme Regis, West Dorset, England |

||||

|

H. ociendentatus |

||||||

|

H. wymani |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |

|

|||

|

"Hylerpeton" intermedium[29] |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XII, coal-group 26 |

|

|||

Plants

Cycads

| Cycads reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

A. decurrens |

| |||||

|

A. discrepans |

||||||

|

A. cf. urophylla |

||||||

|

Eusphenopteris |

E. obtusiloba |

|||||

|

E. trigonophylla |

||||||

|

Holcospermum |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Karinopteris |

K. cf. dernoncourtii |

|||||

|

K. grandepinnata |

||||||

|

K. tennesseana |

||||||

|

Mariopteris |

M. abnormis |

|||||

|

M. comata |

||||||

|

M. disjuncta |

||||||

|

Neuralethopteris |

N. schlehanii |

|||||

|

N. cf. blissi |

||||||

|

N. cf. hollandica |

||||||

|

N. obliqua |

%2C_Geology_(1994)_(20419950116).jpg) | |||||

|

N. tenuifolia |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

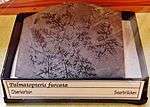

Palmatopteris |

P. alata |

|||||

|

P. furcata |

| |||||

|

Paripteris |

P. pseudogigantea |

%2C_Geology_(1994)_(20446177075).jpg) | ||||

|

S. valida |

||||||

|

Trigonocarpus |

T. parkinsoni |

|||||

Ferns

| Ferns reported from the Joggins Formation[8][24][34] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

A. acicularis |

||||||

|

A. aculeata |

||||||

|

A. asteris |

||||||

|

A. latifolia |

||||||

|

A. cf. stellata |

| |||||

|

Asterophyllites |

A. charaeformis |

|||||

|

A. equisetiformis |

| |||||

|

A. grandis |

||||||

|

Boweria |

B. schatzlarensis |

|||||

|

C. carinatus |

||||||

|

C. cf. goeppertii |

||||||

|

C. suckowi |

_(18196604432).jpg) | |||||

|

indeterminate |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 | ||||

|

Calamodendron |

indeterminate |

_(1871)_(20604766032).jpg) | ||||

|

Corynepteris |

C. angustissima |

| ||||

|

Eucalamites |

indeterminate |

_(17791258913).jpg) | ||||

|

Megaphyton |

M. magnificum |

| ||||

|

Oligocarpia |

O. brongniartii |

|||||

|

Palaeostachya |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Pinnularia |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Renaultia |

R. crepinii |

|||||

|

R. footneri |

||||||

|

R. gracilis |

||||||

|

R. rotundifolia |

||||||

|

R. cf. schatzlarensis |

||||||

|

Senftenbergia |

S. plumosa |

| ||||

|

Sphenophylum |

S. cf. kidstonii |

|||||

|

S. deltiformis |

||||||

|

S. dixonii |

||||||

|

S. effusa |

||||||

|

S. fletcheri |

||||||

|

S. moyseyi |

||||||

|

S. schwerinii |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

Sturia |

S. amoena |

|||||

|

Zeilleria |

Z. delicatula |

.jpg) | ||||

|

Z. frenzlii |

||||||

|

Z. hymenophylloides |

||||||

|

Z. pilosa |

||||||

|

Z. schaumburg-lippeana |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

indeterminate |

|||||

Lycophytes

| Lycophytes reported from the Joggins Formation[8][24][34] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Bothrodendron |

B. punctatum |

| ||||

|

Cyperites |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Cystosporites |

C. diabolicus |

|||||

|

Diaphorodendron |

indeterminate |

| ||||

|

L. aculeatum |

| |||||

|

"L". bretonense |

||||||

|

L. cf. fusiforme |

||||||

|

L. lycopodioides |

| |||||

|

L. cf. obovatum |

||||||

|

L. worthenii |

||||||

|

Lepidophloios |

L. laricinus |

| ||||

|

Lepidostrobophyllum |

L. lanceolatum |

|||||

|

L. majus |

||||||

|

L. morrisianum |

||||||

|

L. olryi |

||||||

|

L. ornatus |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

S. cf. laevigata |

.jpg) | |||||

|

S. mamillaris |

.jpg) | |||||

|

S. cf. rayosa |

||||||

|

S. cf. rugosa |

||||||

|

S. scutellata |

||||||

|

Sigillariostrobus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

S. ficoides |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 |  | |||

|

Syringodendron |

indeterminate |

| ||||

|

Tuberculatisporites[8] |

T. mamillarus |

|||||

|

Ulodendron |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

unidentified lepidocarpal |

indeterminate |

|||||

Progymnosperms

| Progymnosperms reported from the Joggins Formation[24][34] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Adiantites |

A. adiantoides |

|||||

|

Cordaianthus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

C. dawsoni |

| |||||

|

C. palmaeformis |

||||||

|

C. principalis |

||||||

|

Cordiaxylon |

C. cf. dumusum |

|||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

Mesoxylon |

M. cf. sutcliff |

)_(18192166502).jpg) | ||||

|

indeterminate |

Coal Mine Point | Division 4, Section XV, coal-group 15 | ||||

|

Pseudadiantites |

P. rhomboideus |

|||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

Protists

| Protists reported from the Joggins Formation[24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Ammobaculites |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Ammotium |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Trochammina |

indeterminate |

|||||

Ichnogenera

Invertebrate ichnofossils

| Invertebrate trace fossils reported from the Joggins Formation[12][24] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Acanthichnus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

Cochlichnus |

indeterminate |

| ||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

Diplopodichnus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Fuershichnus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

.jpg) | |||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

.jpg) | |||||

|

Laevicyclus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Limulocubichnus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Lingulichnus |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Palaeophycus |

P. hebrati |

|||||

|

P. tekularis |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

P. beverlexensis |

||||||

|

P. montanus |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

R. jenese |

||||||

|

S. linearis |

| |||||

|

Stiaria |

indeterminate |

|||||

|

Taenidium |

T. annulata |

|||||

|

T. barretti |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

| |||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

T. pollardi |

||||||

|

Undichnia |

indeterminate |

|||||

Vertebrate ichnofossils

| Vertebrate trace fossils reported from the Joggins Formation[24][35] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Images | |

|

Anthichnium |

A. obtusum |

|||||

|

A. quadratum |

||||||

|

Asperipes |

A. avipes |

|||||

|

A. flexilis |

||||||

|

Barillopus |

B. arctus |

|||||

|

B. confusus |

||||||

|

B. unguifer |

||||||

|

Baropezia |

B. sydnensis |

|||||

|

Cursipes |

C. dawsoni |

|||||

|

Dromillopus |

D. celer |

|||||

|

D. quadrifidus |

||||||

|

Hylopus |

H. minor |

|||||

|

H. hardingi |

||||||

|

L. mcnaughtoni |

| |||||

|

Matthewichnus |

M. velox |

|||||

|

Ornithoides |

O. trifudus |

|||||

|

Pseudobradypus |

P. caudifer |

|||||

|

P. unguifer |

||||||

|

indeterminate |

||||||

|

Quadropedia |

Q. levis |

|||||

|

Salichnium |

S. adamsii |

|||||

|

indeterminate |

indeterminate |

tetrapod tracks[22] |

||||

See also

- Coal forest

- Geology of Nova Scotia

- List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in Nova Scotia

- List of World Heritage sites in Canada

References

- "Joggins Fossil Cliffs". UNESCO. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Falcon-Lang, Howard J. (2009). "Earliest history of coal mining and grindstone quarrying at Joggins, Nova Scotia, and its implications for the meaning of the place name "Joggins"". Atlantic Geology. Atlantic Geoscience Society.

- Calder, John H. (2006). ""Coal Age Galapagos": Joggins and the Lions of Nineteenth Century Geology". Atlantic Geology. Atlantic Geoscience Society.

- Gerriets, Marilyn (Autumn 1991). "The Impact of the General Mining Association on the Nova Scotia Coal Industry, 1826-1850". Acadiensis. 21 (1): 54–84.

- Quann, Sarah L.; Young, Amanda B.; Laroque, Colin P.; Falcon-Lang, Howard J.; Gibling, Martin R. (20 December 2010). "Dendrochronological dating of coal mine workings at the Joggins Fossil Cliffs, Nova Scotia, Canada". Atlantic Geology. Atlantic Geoscience Society.

- Summerby-Murray, Robert (2007). "Interpreting Personalized Industrial Heritage in the Mining Towns of Cumberland County, Nova Scotia: Landscape Examples from Springhill and River Hebert". The Politics and Memory of Deindustrialization in Canada. 35 (2).

- McKay, Ian (1986). "The Realm of Uncertainty: The Experience of Work in the Cumberland Coal Mines, 1873-1927". Acadiensis. 16 (1): 3–57.

- Calder, John H.; Gibling, Martin R.; Scott, Andrew C.; Davies, Sarah J.; Hebert, Brian L. (2006). "A fossil lycopsid forest succession in the classic Joggins section of Nova Scotia: Paleoecology of a disturbance-prone Pennsylvanian wetland". Wetlands Through Time. 399.

- Rygel, Michael C.; Shipley, Brian C. (2005). ""Such a section as never was put together before": Logan, Dawson, Lyell, and mid-Nineteenth-Century measurements of the Pennsylvanian Joggins section of Nova Scotia". Atlantic Geology. Atlantic Geoscience Society.

- Lyell, Charles; Dawson, J. W. (1 February 1853). "On the Remains of a Reptile (Dendrerpeton Acadianum, Wyman and Owen) and of a Land Shell discovered in the Interior of an Erect Fossil Tree in the Coal Measures of Nova Scotia". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. Geological Society. 9: 58–67.

- Davies, S.J.; Gibling, M. R.; Rygel, M. C.; Calder, J. H.; Skilliter, D.M. (2005). "The Pennsylvanian Joggins Formation of Nova Scotia: sedimentological log and stratigraphic framework of the historic fossil cliffs". Atlantic Geology. Atlantic Geoscience Society.

- Joggins Fossil Centre. "Joggins Fossil Institute Abstracts 2018: 1st Joggins Research Symposium". Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Byron, Jennie. "Sir Hugh Fletcher and the Fletcher Geology Club - Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Matthew, George Frederick (1903). "On batrachian and other footprints from the Coal Measures of Joggins, N.S.". Bulletin of the Natural History Society of New Brunswick. Natural History Society of New Brunswick. 5: 103–108.