Japanese yen

The yen (Japanese: 円, Hepburn: en, symbol: ¥; code: JPY; also abbreviated as JP¥) is the official currency of Japan. It is the third most traded currency in the foreign exchange market after the United States dollar and the Euro.[5] It is also widely used as a reserve currency after the U.S. dollar, the Euro, and the U.K. pound sterling.

| Japanese yen | |

|---|---|

| 日本円 (Japanese) | |

The 6 types of coins of the Japanese yen | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | JPY |

| Number | 392 |

| Exponent | 0 |

| Denominations | |

| Superunit | |

| 100 (before tax) | $ |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | sen (錢 or 銭) |

| 1⁄1000 | rin (厘) |

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency do(es) not have a morphological plural distinction. |

| Symbol | ¥ (international) 円 (Japan—present day) 圓 (Japan—traditional) |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | ¥1,000, ¥5,000, ¥10,000 |

| Rarely used | ¥2,000[1][2] |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥50, ¥100, ¥500 |

| Demographics | |

| Official user(s) | |

| Unofficial user(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Bank of Japan |

| Website | www |

| Printer | National Printing Bureau |

| Website | www |

| Mint | Japan Mint |

| Website | www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 0.5% 2019-CPI |

| Source | Statistics Bureau of Japan[4] |

The concept of the yen was a component of the late-19th century Meiji government's modernization program of Japan's economy, which postulated the pursuit of a uniform currency throughout the country, modelled after the European decimal currency system. Before the Meiji Restoration, Japan's feudal fiefs all issued their own money, hansatsu, in an array of incompatible denominations. The New Currency Act of 1871 did away with these and established the yen, which was defined as 1.5 g (0.048 troy ounces) of gold, or 24.26 g (0.780 troy ounces) of silver, as the new decimal currency. The former han (fiefs) became prefectures and their mints private chartered banks, which initially retained the right to print money. To bring an end to this situation, the Bank of Japan was founded in 1882 and given a monopoly on controlling the money supply.[6]

Following World War II the yen lost much of its prewar value. To stabilize the Japanese economy the exchange rate of the yen was fixed at ¥360 per US$1 as part of the Bretton Woods system. When that system was abandoned in 1971, the yen became undervalued and was allowed to float. The yen had appreciated to a peak of ¥271 per US$1 in 1973, then underwent periods of depreciation and appreciation due to the 1973 oil crisis, arriving at a value of ¥227 per US$1 by 1980.

Since 1973, the Japanese government has maintained a policy of currency intervention, and the yen is therefore under a "dirty float" regime. The Japanese government focused on a competitive export market, and tried to ensure a low exchange rate for the yen through a trade surplus. The Plaza Accord of 1985 temporarily changed this situation: the exchange rate fell from its average of ¥239 per US$1 in 1985 to ¥128 in 1988 and led to a peak rate of ¥80 against the U.S. dollar in 1995, effectively increasing the value of Japan’s GDP in US dollar terms to almost that of the United States. Since that time, however, the world price of the yen has greatly decreased. The Bank of Japan maintains a policy of zero to near-zero interest rates and the Japanese government has previously had a strict anti-inflation policy.[7]

Pronunciation and etymology

Yen derives from the Japanese word 圓 (えん, en, [eɴ]; lit. "round"), which borrows its phonetic reading from Chinese yuan, similar to North Korean won and South Korean won. Originally, the Chinese had traded silver in mass called sycees and when Spanish and Mexican silver coins arrived, the Chinese called them "silver rounds" (Chinese: 銀圓; pinyin: yínyuán) for their circular shapes.[8] The coins and the name also appeared in Japan. While the Chinese eventually replaced 圆; 圓 with 元,[note 1] the Japanese continued to use the same word, which was given the shinjitai form 円 in reforms at the end of World War II.

The spelling and pronunciation "yen" is standard in English because when Japan was first encountered by Europeans around the 16th century, Japanese /e/ (え) and /we/ (ゑ) both had been pronounced [je] and Portuguese missionaries had spelled them "ye".[note 2] By the middle of the 18th century, /e/ and /we/ came to be pronounced [e] as in modern Japanese, although some regions retain the [je] pronunciation. Walter Henry Medhurst, who had neither been to Japan nor met any Japanese, having consulted mainly a Japanese-Dutch dictionary, spelled some "e"s as "ye" in his An English and Japanese, and Japanese and English Vocabulary (1830).[10] In the early Meiji era, James Curtis Hepburn, following Medhurst, spelled all "e"s as "ye" in his A Japanese and English dictionary (1867); in Japanese, e and i are slightly palatalized, somewhat as in Russian.[11] That was the first full-scale Japanese-English/English-Japanese dictionary, which had a strong influence on Westerners in Japan and probably prompted the spelling "yen". Hepburn revised most "ye"s to "e" in the 3rd edition (1886)[12] to mirror the contemporary pronunciation, except "yen".[13] This was probably already fixed and has remained so ever since.

History

Introduction

.jpg)

In the 19th century, silver Spanish dollar coins were common throughout Southeast Asia, the China coast, and Japan. These coins had been introduced through Manila over a period of two hundred and fifty years, arriving on ships from Acapulco in Mexico. These ships were known as the Manila galleons. Until the 19th century, these silver dollar coins were actual Spanish dollars minted in the new world, mostly at Mexico City. But from the 1840s, they were increasingly replaced by silver dollars of the new Latin American republics. In the later half of the 19th century, some local coins in the region were made in the resemblance of the Mexican peso. The first of these local silver coins was the Hong Kong silver dollar coin that was minted in Hong Kong between 1866 and 1869. The Chinese were slow to accept unfamiliar coinage and preferred the familiar Mexican dollars, and so the Hong Kong government ceased minting these coins and sold the mint machinery to Japan.

The Japanese then decided to adopt a silver dollar coinage under the name of 'yen', meaning 'a round object'. The yen was officially adopted by the Meiji government in an Act signed on June 27, 1871.[14] The new currency was gradually introduced beginning from July of that year. The yen was therefore basically a dollar unit, like all dollars, descended from the Spanish Pieces of eight, and up until 1873 all the dollars in the world had more or less the same value. The yen replaced Tokugawa coinage, a complex monetary system of the Edo period based on the mon. The New Currency Act of 1871 stipulated the adoption of the decimal accounting system of yen (1, 圓), sen (1⁄100, 錢), and rin (1⁄1000, 厘), with the coins being round and manufactured using Western machinery. The yen was legally defined as 0.78 troy ounces (24.26 g) of pure silver, or 1.5 grams of pure gold (as recommended by the European Congress of Economists in Paris in 1867; the 5-yen coin was equivalent to the Argentine 5 peso fuerte coin[15]), hence putting it on a bimetallic standard.

Following the silver devaluation of 1873, the yen devalued against the U.S. dollar and the Canadian dollar (since those two countries adhered to a gold standard), and by 1897 the yen was worth only about US$0.50. In that year, Japan adopted a gold exchange standard and hence froze the value of the yen at $0.50.[16] This exchange rate remained in place until Japan left the gold standard in December 1931, after which the yen fell to $0.30 by July 1932 and to $0.20 by 1933.[17] It remained steady at around $0.30 until the start of the Pacific War on December 7, 1941, at which time it fell to $0.23.[18]

The sen and the rin were eventually taken out of circulation at the end of 1953.[19]

Fixed value of the yen to the U.S. dollar

No true exchange rate existed for the yen between December 7, 1941, and April 25, 1949; wartime inflation reduced the yen to a fraction of its pre-war value. After a period of instability, on April 25, 1949, the U.S. occupation government fixed the value of the yen at ¥360 per US$1 through a United States plan, which was part of the Bretton Woods System, to stabilize prices in the Japanese economy.[20] That exchange rate was maintained until 1971, when the United States abandoned the gold standard, which had been a key element of the Bretton Woods System, and imposed a 10 percent surcharge on imports, setting in motion changes that eventually led to floating exchange rates in 1973.

Undervalued yen

By 1971, the yen had become undervalued. Japanese exports were costing too little in international markets, and imports from abroad were costing the Japanese too much. This undervaluation was reflected in the current account balance, which had risen from the deficits of the early 1960s, to a then-large surplus of US$5.8 billion in 1971. The belief that the yen, and several other major currencies, were undervalued motivated the United States' actions in 1971.

Yen and major currencies float

Following the United States' measures to devalue the dollar in the summer of 1971, the Japanese government agreed to a new, fixed exchange rate as part of the Smithsonian Agreement, signed at the end of the year. This agreement set the exchange rate at ¥308 per US$1. However, the new fixed rates of the Smithsonian Agreement were difficult to maintain in the face of supply and demand pressures in the foreign-exchange market. In early 1973, the rates were abandoned, and the major nations of the world allowed their currencies to float.

Japanese government intervention in the currency market

In the 1970s, Japanese government and business people were very concerned that a rise in the value of the yen would hurt export growth by making Japanese products less competitive and would damage the industrial base. The government therefore continued to intervene heavily in foreign-exchange marketing (buying or selling dollars), even after the 1973 decision to allow the yen to float.

Despite intervention, market pressures caused the yen to continue climbing in value, peaking temporarily at an average of ¥271 per US$1 in 1973, before the impact of the 1973 oil crisis was felt. The increased costs of imported oil caused the yen to depreciate to a range of ¥290 per US$1 to ¥300 per US$1 between 1974 and 1976. The re-emergence of trade surpluses drove the yen back up to ¥211 in 1978. This currency strengthening was again reversed by the second oil shock in 1979, with the yen dropping to ¥227 per US$1 by 1980.

Yen in the early 1980s

During the first half of the 1980s, the yen failed to rise in value even though current account surpluses returned and grew quickly. From ¥221 per US$1 in 1981, the average value of the yen actually dropped to ¥239 per US$1 in 1985. The rise in the current account surplus generated stronger demand for yen in foreign-exchange markets, but this trade-related demand for yen was offset by other factors. A wide differential in interest rates, with United States interest rates much higher than those in Japan, and the continuing moves to deregulate the international flow of capital, led to a large net outflow of capital from Japan. This capital flow increased the supply of yen in foreign-exchange markets, as Japanese investors changed their yen for other currencies (mainly dollars) to invest overseas. This kept the yen weak relative to the dollar and fostered the rapid rise in the Japanese trade surplus that took place in the 1980s.

Effect of the Plaza Accord

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

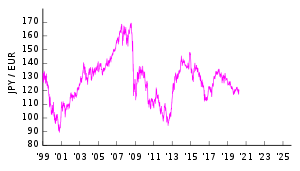

In 1985, a dramatic change began. Finance officials from major nations signed an agreement (the Plaza Accord) affirming that the dollar was overvalued (and, therefore, the yen undervalued). This agreement, and shifting supply and demand pressures in the markets, led to a rapid rise in the value of the yen. From its average of ¥239 per US$1 in 1985, the yen rose to a peak of ¥128 in 1988, virtually doubling its value relative to the dollar. After declining somewhat in 1989 and 1990, it reached a new high of ¥123 to US$1 in December 1992. In April 1995, the yen hit a peak of under 80 yen per dollar, temporarily making Japan's economy nearly the size of that of the US.[21]

Post-bubble years

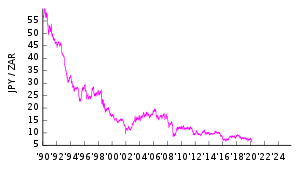

The yen declined during the Japanese asset price bubble and continued to do so afterwards, reaching a low of ¥134 to US$1 in February 2002. The Bank of Japan's policy of zero interest rates has discouraged yen investments, with the carry trade of investors borrowing yen and investing in better-paying currencies (thus further pushing down the yen) estimated to be as large as $1 trillion.[22] In February 2007, The Economist estimated that the yen was 15% undervalued against the dollar, and as much as 40% undervalued against the euro.[23]

After the global economic crisis of 2008

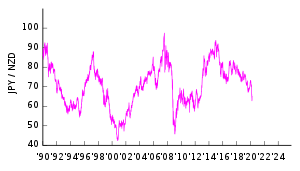

However, this trend of depreciation reversed after the global economic crisis of 2008. Other major currencies, except the Swiss franc, have been declining relative to the yen.

On April 4, 2013, the Bank of Japan announced that they would expand their Asset Purchase Program by $1.4 trillion in two years. The Bank of Japan hopes to bring Japan from deflation to inflation, aiming for 2% inflation. The amount of purchases is so large that it is expected to double the money supply. But this move has sparked concerns that the authorities in Japan are deliberately devaluing the yen in order to boost exports.[24] However, the commercial sector in Japan worried that the devaluation would trigger an increase in import prices, especially for energy and raw materials.

Coins

.jpg)

Coins were introduced in 1870. There were silver 5-, 10-, 20- and 50-sen and 1-yen, and gold 2-, 5-, 10- and 20-yen. Gold 1-yen were introduced in 1871, followed by copper 1-rin, 1⁄2-, 1- and 2-sen in 1873.

| 10 Japanese yen | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Obverse: Lettering: 日 本 国 & 十 円. Phoenix Hall of Byōdō-in displayed. | Reverse: Face value. Lettering: Lettering: 10 昭和五十六年 (Shōwa 56 or 1981). |

| 1,773,000,000 coins minted (1951 to 1958) | |

Cupronickel 5-sen coins were introduced in 1889. In 1897, the silver 1-yen coin was demonetized and the sizes of the gold coins were reduced by 50%, with 5-, 10- and 20-yen coins issued. In 1920, cupro-nickel 10-sen coins were introduced.

Production of silver coins ceased in 1938, after which a variety of base metals were used to produce 1-, 5- and 10-sen coins during the Second World War. Clay 5- and 10-sen coins were produced in 1945, but not issued for circulation.

After the war, brass 50-sen, 1- and 5-yen were introduced between 1946 and 1948. In 1949, the current type of holed 5-yen was introduced, followed by bronze 10-yen (of the type still in circulation) in 1951.

Coins in denominations of less than 1-yen became invalid on December 31, 1953, following enforcement of the Small Currency Disposition and Fractional Rounding in Payments Act (小額通貨の整理及び支払金の端数計算に関する法律, Shōgaku tsūka no seiri oyobi shiharaikin no hasūkeisan ni kan suru hōritsu).

In 1955, the current type of aluminium 1-yen was introduced, along with unholed, nickel 50-yen. In 1957, silver 100-yen pieces were introduced, followed by the holed 50-yen coin in 1959. These were replaced in 1967 by the current cupro-nickel type, along with a smaller 50-yen coin. In 1982, the first 500-yen coins were introduced.[26]

The date (expressed as the year in the reign of the emperor at the time the coin was stamped) is on the reverse of all coins, and, in most cases, country name (through 1945, Dai Nippon (大日本, "Great Japan"); after 1945, Nippon-koku (日本国, "State of Japan") and the value in kanji is on the obverse, except for the present 5-yen coin where the country name is on the reverse.

Alongside with the 5-Swiss franc coin and the rarely used 5-Cuban convertible peso coin, the 500-yen coin is one of the highest-valued coin to be used regularly in the world, with value of US$4.5 as of October 2017. Because of this high face value, the 500-yen coin has been a favorite target for counterfeiters; it was counterfeited to such an extent, that in 2000, a new series of coins was issued with various security features, but counterfeiting continued.

The 1-yen coin is made out of 100% aluminium and can float on water if placed correctly.

On various occasions, commemorative coins are minted, often in gold and silver with face values up to 100,000 yen.[27] The first of these were silver ¥100 and ¥1000 Summer Olympic coins issued on the occasion of the 1964 games. Recently this practice is undertaken with the 500-yen coin, the first two types were issued in 1985, in commemoration of the science and technology exposition in Tsukuba and the 100th anniversary of the Governmental Cabinet system. The current commemorative 500- and 1000-yen coin series honouring the 47 prefectures of Japan commenced in 2008, with 47 unique designs planned for each denomination. Only one coin per customer is available from banks in each prefecture. 100,000 of each 1000-yen silver coin have been minted. Even though all commemorative coins can be spent like ordinary (non-commemorative) coins, they are not seen often in typical daily use and normally do not circulate.

Instead of displaying the Gregorian calendar year of mintage like most nations' coins, yen coins instead display the year of the current emperor's reign. For example, a coin minted in 2009, would bear the date Heisei 21 (the 21st year of Emperor Akihito's reign).[28]

| Currently circulating coins[29] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Technical parameters | Description | Date of first minting | |||||

| Diameter | Thickness | Mass | Composition | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | |||

| ¥1 | 20 mm | 1.5 mm | 1 g | 100% aluminium | Smooth | Young tree, state title, value | Value, year of minting | 1955 | |

| ¥5 | 22 mm | 1.5 mm | 3.75 g | 60–70% copper 30–40% zinc |

Smooth | Ear of Rice, gear, water, value | State title, year of minting | 1959 | |

| ¥10 | 23.5 mm | 1.5 mm | 4.5 g | 95% copper 3–4% zinc 1–2% tin |

Reeded | Phoenix Hall, Byōdō-in, state title, value | Evergreen tree, value, year of minting | 1951 (rarely) | |

| Smooth | 1959 | ||||||||

| ¥50 | 21 mm | 1.7 mm | 4 g | Cupronickel 75% copper 25% nickel |

Reeded | Chrysanthemum, state title, value | Value, year of minting | 1967 | |

| ¥100 | 22.6 mm | 1.7 mm | 4.8 g | Cupronickel 75% copper 25% nickel |

Reeded | Cherry blossoms, state title, value | Value, year of minting | 1967 | |

| ¥500 | 26.5 mm | 2 mm | 7 g | (Nickel-brass) 72% copper 20% zinc 8% nickel |

Reeded slantingly | Paulownia, state title, value | Bamboo, Mandarin orange, Value, year of minting | 2000 | |

| These images are to scale at 2.5 pixels per millimetre. For table standards, see the coin specification table. | |||||||||

Due to the great differences in style, size, weight and the pattern present on the edge of the coin they are very easy for people with visual impairments to tell apart from one another.

| Unholed | Holed | |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth edge | ¥1 (light) ¥10 (medium) |

¥5 |

| Reeded edge | ¥100 (medium) ¥500 (heavy) | ¥50 |

Current banknotes

The issuance of the yen banknotes began in 1872, two years after the currency was introduced. Throughout its history, the denominations have ranged from 10 yen to 10,000 yen; since 1984, the lowest-valued banknote is the 1,000 yen note.

Before and during World War II, various bodies issued banknotes in yen, such as the Ministry of Finance and the Imperial Japanese National Bank. The Allied forces also issued some notes shortly after the war. Since then, the Bank of Japan has been the exclusive note issuing authority. The bank has issued five series after World War II. Series E, the current series introduced in 2004, consists of ¥1000, ¥5000, and ¥10,000 notes. The EURion constellation pattern is present in the designs.

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main Color | Description | Series | Date of issue | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||||

|

|

¥1000 | 150 × 76 mm | Blue | Hideyo Noguchi | Mount Fuji, Lake Motosu and cherry blossoms | Series E | November 1, 2004 |

_front.jpg) |

|

¥2000 | 154 × 76 mm | Green | Shureimon | The Tale of Genji | Series D | July 19, 2000 |

_(Anverso).jpg) |

_(Reverso).jpg) |

¥5000 | 156 × 76 mm | Purple | Ichiyō Higuchi | Kakitsubata-zu (Painting of irises, a work by Ogata Kōrin) | Series E | November 1, 2004 |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

¥10,000 | 160 × 76 mm | Brown | Fukuzawa Yukichi | Statue of hōō (phoenix) from Byōdō-in Temple | Series E | November 1, 2004 |

Japan is generally considered a cash-based society, with 38% of payments in Japan made by cash in 2014.[30] Possible explanations are that cash payments protect one's privacy, merchants do not have to wait for payment, and it does not carry any negative connotation like credit.

New banknotes

On April 9, 2019, Finance Minister Tarō Asō announced new designs for the ¥1000, ¥5000, and ¥10,000 notes, for use beginning in 2024.[31] The ¥1000 bill will feature Kitasato Shibasaburō and The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the ¥5000 bill will feature Tsuda Umeko and wisteria flowers, and the ¥10,000 bill will feature Shibusawa Eiichi and Tokyo Station.

| Series F (2024, scheduled) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main

Color |

Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | ||||

|

|

¥1000 | 150 × 76 mm | Blue | Kitasato Shibasaburo | The Great Wave off Kanagawa (from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series by Hokusai) | 2024, scheduled |

|

|

¥5000 | 156 × 76 mm | Purple | Umeko Tsuda | Wisteria flowers | |

|

|

¥10,000 | 160 × 76 mm | Brown | Shibusawa Eiichi | Tokyo Station (Marunouchi side) | |

Determinants of value

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code (symbol) | % of daily trades (bought or sold) (April 2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | USD (US$) | 88.3% | |

2 | EUR (€) | 32.3% | |

3 | JPY (¥) | 16.8% | |

4 | GBP (£) | 12.8% | |

5 | AUD (A$) | 6.8% | |

6 | CAD (C$) | 5.0% | |

7 | CHF (CHF) | 5.0% | |

8 | CNY (元) | 4.3% | |

9 | HKD (HK$) | 3.5% | |

10 | NZD (NZ$) | 2.1% | |

11 | SEK (kr) | 2.0% | |

12 | KRW (₩) | 2.0% | |

13 | SGD (S$) | 1.8% | |

14 | NOK (kr) | 1.8% | |

15 | MXN ($) | 1.7% | |

16 | INR (₹) | 1.7% | |

17 | RUB (₽) | 1.1% | |

18 | ZAR (R) | 1.1% | |

19 | TRY (₺) | 1.1% | |

20 | BRL (R$) | 1.1% | |

21 | TWD (NT$) | 0.9% | |

22 | DKK (kr) | 0.6% | |

23 | PLN (zł) | 0.6% | |

24 | THB (฿) | 0.5% | |

25 | IDR (Rp) | 0.4% | |

26 | HUF (Ft) | 0.4% | |

27 | CZK (Kč) | 0.4% | |

28 | ILS (₪) | 0.3% | |

29 | CLP (CLP$) | 0.3% | |

30 | PHP (₱) | 0.3% | |

31 | AED (د.إ) | 0.2% | |

32 | COP (COL$) | 0.2% | |

33 | SAR (﷼) | 0.2% | |

34 | MYR (RM) | 0.1% | |

35 | RON (L) | 0.1% | |

| Other | 2.2% | ||

| Total[note 3] | 200.0% | ||

Beginning in December 1931, Japan gradually shifted from the gold standard system to the managed currency system.[33]

The relative value of the yen is determined in foreign exchange markets by the economic forces of supply and demand. The supply of the yen in the market is governed by the desire of yen holders to exchange their yen for other currencies to purchase goods, services, or assets. The demand for the yen is governed by the desire of foreigners to buy goods and services in Japan and by their interest in investing in Japan (buying yen-denominated real and financial assets).

Since the 1990s, the Bank of Japan, the country's central bank, has kept interest rates low in order to spur economic growth. Short-term lending rates have responded to this monetary relaxation and fell from 3.7% to 1.3% between 1993 and 2008.[34] Low interest rates combined with a ready liquidity for the yen prompted investors to borrow money in Japan and invest it in other countries (a practice known as carry trade). This has helped to keep the value of the yen low compared to other currencies.

International reserve currency

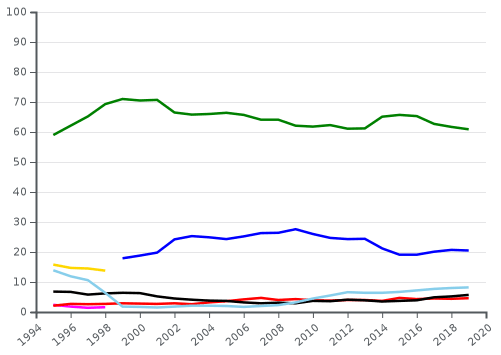

The percental composition of currencies of official foreign exchange reserves from 1995 to 2019.[35][36][37]

SDR basket

The special drawing rights (SDR) valuation is an IMF basket of currencies, including the Japanese yen. The SDR is linked to a basket of five different currencies, with 41.73% for the U.S. dollar, 30.93% for the Euro, 10.92% for the Chinese renminbi, 8.33% for the Japanese yen, and 8.09% for the pound sterling (as of 2016).[38] The percentage for the yen has, however, declined from 18% in 2000. The exchange rate for the Japanese yen is expressed in terms of currency units per U.S. dollar; other rates are expressed as U.S. dollars per currency unit. The SDR currency value is calculated daily and the valuation basket is reviewed and adjusted every five years. The SDR was created in 1969, to support the fixed exchange system.

Historical exchange rate

Before the war commenced, the yen traded on an average of 3.6 yen to the dollar. During the war, because of overprinting and inflation as the Empire occupied more territory, the yen went as low as 600 yen to the USD.

When McArthur and the US forces entered Japan in 1945, they decreed an official conversion rate of 15 yen to the USD.

Within 1945-1946: the rate tanked to 50 yen to the USD because of the ongoing inflation. During the first half of 1946, the rate fluctuated to 66 yen to the USD and eventually plummeting to 600 yen to the dollar by 1947 because of the failure of the economic remedies.

Eventually, the peg was officially moved to 270 yen to the dollar in 1948 before being adjusted again from 1949–1971 to 360 yen to the dollar.

The table below shows the monthly average of the U.S. dollar–yen spot rate (JPY per USD) at 17:00 JST:[39][40]

| Year | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1949–1971 | 360 | |||||||||||

| 1972 | 308 | |||||||||||

| 1973 | 301.15 | 270.00 | 265.83 | 265.50 | 264.95 | 265.30 | 263.45 | 265.30 | 265.70 | 266.68 | 279.00 | 280.00 |

| 1974 | 299.00 | 287.60 | 276.00 | 279.75 | 281.90 | 284.10 | 297.80 | 302.70 | 298.50 | 299.85 | 300.10 | 300.95 |

| 1975 | 297.85 | 286.60 | 293.80 | 293.30 | 291.35 | 296.35 | 297.35 | 297.90 | 302.70 | 301.80 | 303.00 | 305.15 |

| 1976 | 303.70 | 302.25 | 299.70 | 299.40 | 299.95 | 297.40 | 293.40 | 288.76 | 287.30 | 293.70 | 296.45 | 293.00 |

| 1977 | 288.25 | 283.25 | 277.30 | 277.50 | 277.30 | 266.50 | 266.30 | 267.43 | 264.50 | 250.65 | 244.20 | 240.00 |

| 1978 | 241.74 | 238.83 | 223.40 | 223.90 | 223.15 | 204.50 | 190.80 | 190.00 | 189.15 | 176.05 | 197.80 | 195.10 |

| 1979 | 201.40 | 202.35 | 209.30 | 219.15 | 219.70 | 217.00 | 216.90 | 220.05 | 223.45 | 237.80 | 249.50 | 239.90 |

| 1980 | 237.73 | 244.07 | 248.61 | 251.45 | 228.06 | 218.11 | 220.91 | 224.34 | 214.95 | 209.21 | 212.99 | 209.79 |

| 1981 | 202.19 | 205.76 | 208.84 | 215.07 | 220.78 | 224.21 | 232.11 | 233.62 | 229.83 | 231.40 | 223.76 | 219.02 |

| 1982 | 224.55 | 235.25 | 240.64 | 244.90 | 236.97 | 251.11 | 255.10 | 258.67 | 262.74 | 271.33 | 265.02 | 242.49 |

| 1983 | 232.90 | 236.27 | 237.92 | 237.70 | 234.78 | 240.06 | 240.49 | 244.36 | 242.71 | 233.00 | 235.25 | 234.34 |

| 1984 | 233.95 | 233.67 | 225.52 | 224.95 | 230.67 | 233.29 | 242.72 | 242.24 | 245.19 | 246.89 | 243.29 | 247.96 |

| 1985 | 254.11 | 260.34 | 258.43 | 251.67 | 251.57 | 248.95 | 241.70 | 237.20 | 236.91 | 214.84 | 203.85 | 202.75 |

| 1986 | 200.05 | 184.62 | 178.83 | 175.56 | 166.89 | 167.82 | 158.65 | 154.11 | 154.78 | 156.04 | 162.72 | 162.13 |

| 1987 | 154.48 | 153.49 | 151.56 | 142.96 | 140.47 | 144.52 | 150.20 | 147.57 | 143.03 | 143.48 | 135.25 | 128.25 |

| 1988 | 127.44 | 129.26 | 127.23 | 124.88 | 124.74 | 127.20 | 133.10 | 133.63 | 134.45 | 128.85 | 123.16 | 123.63 |

| 1989 | 127.24 | 127.77 | 130.35 | 132.01 | 138.40 | 143.92 | 140.63 | 141.20 | 145.06 | 141.99 | 143.55 | 143.62 |

| 1990 | 145.09 | 145.54 | 153.19 | 158.50 | 153.52 | 153.78 | 149.23 | 147.46 | 138.96 | 129.73 | 129.01 | 133.72 |

| 1991 | 133.65 | 130.44 | 137.09 | 137.15 | 138.02 | 139.83 | 137.98 | 136.85 | 134.59 | 130.81 | 129.64 | 128.07 |

| 1992 | 125.05 | 127.53 | 132.75 | 133.59 | 130.55 | 126.90 | 125.66 | 126.34 | 122.72 | 121.14 | 123.84 | 123.98 |

| 1993 | 125.02 | 120.97 | 117.02 | 112.37 | 110.23 | 107.29 | 107.77 | 103.72 | 105.27 | 106.94 | 107.81 | 109.72 |

| 1994 | 111.49 | 106.14 | 105.12 | 103.48 | 104.00 | 102.69 | 98.54 | 99.86 | 98.79 | 98.40 | 98.00 | 100.17 |

| 1995 | 99.79 | 98.23 | 90.77 | 83.53 | 85.21 | 84.54 | 87.24 | 94.56 | 100.31 | 100.68 | 101.89 | 101.86 |

| 1996 | 105.81 | 105.70 | 105.85 | 107.40 | 106.49 | 108.82 | 109.25 | 107.84 | 109.76 | 112.30 | 112.27 | 113.74 |

| 1997 | 118.18 | 123.01 | 122.66 | 125.47 | 118.91 | 114.31 | 115.10 | 117.89 | 120.74 | 121.13 | 125.35 | 129.52 |

| 1998 | 129.45 | 125.85 | 128.83 | 131.81 | 135.08 | 140.35 | 140.66 | 144.76 | 134.50 | 121.33 | 120.61 | 117.40 |

| 1999 | 113.14 | 116.73 | 119.71 | 119.66 | 122.14 | 120.81 | 119.76 | 113.30 | 107.45 | 106.00 | 104.83 | 102.61 |

| 2000 | 105.21 | 109.34 | 106.62 | 105.35 | 108.13 | 106.13 | 107.90 | 108.02 | 106.75 | 108.34 | 108.87 | 112.21 |

| 2001 | 117.10 | 116.10 | 121.21 | 123.77 | 121.83 | 122.19 | 124.63 | 121.53 | 118.91 | 121.32 | 122.33 | 127.32 |

| 2002 | 132.66 | 133.53 | 131.15 | 131.01 | 126.39 | 123.44 | 118.08 | 119.03 | 120.49 | 123.88 | 121.54 | 122.17 |

| 2003 | 118.67 | 119.29 | 118.49 | 119.82 | 117.26 | 118.27 | 118.65 | 118.81 | 115.09 | 109.58 | 109.18 | 107.87 |

| 2004 | 106.39 | 106.54 | 108.57 | 107.31 | 112.27 | 109.45 | 109.34 | 110.41 | 110.05 | 108.90 | 104.86 | 103.82 |

| 2005 | 103.27 | 104.84 | 105.30 | 107.35 | 106.94 | 108.62 | 111.94 | 110.65 | 111.03 | 114.84 | 118.45 | 118.60 |

| 2006 | 115.33 | 117.81 | 117.31 | 117.13 | 111.53 | 114.57 | 115.59 | 115.86 | 117.02 | 118.59 | 117.33 | 117.26 |

| 2007 | 120.59 | 120.49 | 117.29 | 118.81 | 120.77 | 122.64 | 121.56 | 116.74 | 115.01 | 115.77 | 111.24 | 112.28 |

| 2008 | 107.60 | 107.18 | 100.83 | 102.41 | 104.11 | 106.86 | 106.76 | 109.24 | 106.71 | 100.20 | 96.89 | 91.21 |

| 2009 | 90.35 | 92.53 | 97.83 | 98.92 | 96.43 | 96.58 | 94.49 | 94.90 | 91.40 | 90.28 | 89.11 | 89.52 |

| 2010 | 91.26 | 90.28 | 90.56 | 93.43 | 91.79 | 90.89 | 87.67 | 85.44 | 84.31 | 81.80 | 82.43 | 83.38 |

| 2011 | 82.63 | 82.52 | 81.82 | 83.34 | 81.23 | 80.49 | 79.44 | 77.09 | 76.78 | 76.72 | 77.50 | 77.81 |

| 2012 | 76.94 | 78.47 | 82.37 | 81.42 | 79.70 | 79.27 | 78.96 | 78.68 | 78.17 | 78.97 | 80.92 | 83.60 |

| 2013 | 89.15 | 93.07 | 94.73 | 97.74 | 101.01 | 97.52 | 99.66 | 97.83 | 99.30 | 97.73 | 100.04 | 103.42 |

| 2014 | 103.94 | 102.02 | 102.30 | 102.54 | 101.78 | 102.05 | 101.73 | 102.95 | 107.16 | 108.03 | 116.24 | 119.29 |

| 2015 | 118.25 | 118.59 | 120.37 | 119.57 | 120.82 | 123.7 | 123.31 | 123.17 | 120.13 | 119.99 | 122.58 | 121.78 |

| 2016 | 118.18 | 115.01 | 113.05 | 109.72 | 109.24 | 105.44 | 103.97 | 101.28 | 101.99 | 103.81 | ||

| 2017 | ||||||||||||

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Month | ||||||||||||

| Current JPY exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD USD INR CNY KRW |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD USD INR CNY KRW |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD USD INR CNY KRW |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD USD INR CNY KRW |

| From fxtop.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD USD INR CNY KRW |

See also

- Japan Mint

- Japanese military yen

- Economy of Japan

- Capital flows in Japan

- Monetary and fiscal policy of Japan

- Balance of payments accounts of Japan (1960–90)

- List of countries by leading trade partners

- List of the largest trading partners of Japan

Older currency

- Japanese mon (currency)

- Koban (coin)

- Ryō (Japanese coin)

- Wadōkaichin

Notes

- 元; yuán is not a simplified form of 圆; 圓; yuán, but a completely different character. One of the reasons for replacements is said to be that the previous character had too many strokes.[8] Both characters have the same pronunciation in Mandarin, but not in Japanese. In 1695, certain Japanese coins were issued whose surface has the character gen (元), but this is an abbreviation of the era name Genroku (元禄).

- It is known that in ancient Japanese there were distinct syllables /e/ /we/ /je/. From middle of the 10th century, /e/ (え) had merged with /je/, and both were pronounced [je], while a kana for /je/ had disappeared. Around the 13th century, /we/ (ゑ) and /e/ ceased to be distinguished (in pronunciation, but not in writing system) and both came to be pronounced [je].[9]

- The total sum is 200% because each currency trade always involves a currency pair; one currency is sold (e.g. US$) and another bought (€). Therefore each trade is counted twice, once under the sold currency ($) and once under the bought currency (€). The percentages above are the percent of trades involving that currency regardless of whether it is bought or sold, e.g. the U.S. Dollar is bought or sold in 88% of all trades, whereas the Euro is bought or sold 32% of the time.

References

Citations

- P. Sean Bramble (2004). Culture Shock!: Japan. Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company. p. 107.

- Akiko Kondo (September 6, 2006). "Unwanted and unloved, 2,000 yen bills find few fans". The Japan Times. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Aung, Htin Lynn (January 30, 2019). "CBM permits border trades in yen and yuan denominations". The Myanmar Times.

- "Statistics Bureau Home Page/Consumer Price Index". Stat.go.jp. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- "Foreign exchange turnover in April 2013: preliminary global results" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Mitsura Misawa (2007). Cases on International Business and Finance in Japanese Corporations. Hong Kong University Press. p. 152.

- "History of Japanese Yen". Currency History.

- Ryuzo Mikami, an article about the yen in Heibonsha World Encyclopedia, Kato Shuichi(ed.), Vol. 3, Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2007.

- S. Hashimoto (1950). 国語音韻の変遷 [The History of Japanese Phonology] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

- Medhurst (1830), p. 296.

- Hepburn (1867).

- "明治学院大学図書館 - 和英語林集成デジタルアーカイブス". www.meijigakuin.ac.jp.

- 明治学院大学図書館 - 和英語林集成デジタルアーカイブス (in Japanese). Meijigakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- A. Piatt Andrew, Quarterly Journal of Economics, "The End of the Mexican Dollar", 18:3:321–356, 1904, p. 345

- (in Spanish) Historia de la moneda

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved July 9, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- pp. 347–348, "Average Exchange Rate: Banking and the Money Market", Japan Year Book 1933, Kenkyusha Press, Foreign Association of Japan, Tokyo

- pp. 332–333, "Exchange and Interest Rates", Japan Year Book 1938–1939, Kenkyusha Press, Foreign Association of Japan, Tokyo

- A law of the abolition of currencies in a small denomination and rounding off a fraction, July 15, 1953 Law No.60 (小額通貨の整理及び支払金の端数計算に関する法律, Shōgakutsūka no seiri oyobi shiharaikin no hasūkeisan ni kansuru hōritsu))

- p. 1179, "Japan – Money, Weights and Measures", The Statesman's Year-Book 1950, Steinberg, S. H., Macmillan, New York

- Hongo, Jun, "Despite mounting debt, yen still a safe haven", Japan Times, September 13, 2011, p. 3.

- Kambayashi, Satoshi (February 1, 2007). "What keeps bankers awake at night?". The Economist. London. Archived from the original on February 20, 2007. (Note: archive contains original version of article in full)

- Kambayashi, Satoshi (February 8, 2007). "Carry on living dangerously". The Economist. London. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. (Note: archive contains original version of article in full)

- "Japan aims to jump-start economy with $1.4tn of quantitative easing". The Guardian. April 4, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2009). Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801–1900 (6 ed.). Krause. p. 862. ISBN 978-0-89689-940-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Japan Mint. "Number of Coin Production (calendar year)". Archived from the original on November 10, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

- Japan Mint. "Commemorative Coins issued up to now". Archived from the original on November 9, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

- Japan Mint. "Designs of circulating coins". Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 18, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Soble, Jonathan. "Cash remains king in Japan". Financial Times.

- "Japan announces new ¥10,000, ¥5,000 and ¥1,000 bank notes as Reiwa Era looms". Japan Times. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- "Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2019" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. September 16, 2019. p. 10. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Japan Mint. "75th anniversary of Japan's shift from gold standard to managed currency system". Archived from the original on November 7, 2007. Retrieved December 26, 2007.

- Bank of Japan: "Statistics" Archived October 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. 2008.

- For 1995–99, 2006–19: "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)". Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. April 11, 2020.

- For 1999–2005: International Relations Committee Task Force on Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (February 2006), The Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (PDF), Occasional Paper Series, Nr. 43, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, ISSN 1607-1484ISSN 1725-6534 (online).

- Review of the International Role of the Euro (PDF), Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, December 2005, ISSN 1725-2210ISSN 1725-6593 (online).

- "IMF Launches New SDR Basket Including Chinese Renminbi, Determines New Currency Amounts". IMF. September 30, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Bank of Japan: "Foreign Exchange Rates". 2006. Archived June 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Bank of Japan: US.Dollar/Yen Spot Rate at 17:00 in JST, Average in the Month, Tokyo Market Archived June 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine for duration January 1980 ~ September 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2016

Sources

Further reading

- Medhurst, Walter (1830). An English and Japanese, and Japanese and English Vocabulary: Compiled from Native Works. Batavia, Dutch East Indies. OCLC 5452087. OL 23422004M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hepburn, Jaes Curtis (1867). A Japanese and English Dictionary. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press. OCLC 32634467. OL 13132016W.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Siyun-sai Rin-siyo; Hayashi Gahō (1834) [1652]. Nipon o daï itsi ran: ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Translated by Titsingh, Isaac; Klaproth, Julius von. Paris: Oriental Translation Society of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 5850691.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japanese yen. |

| Look up JPY, JP¥, JP円, or 円 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Japanese currency FAQ in Currency Museum, Bank of Japan

- Images of historic and modern Japanese bank notes

- Chart: US dollar in yen) (in German)

- Chart: 100 yen in euros (in German)

- Historical Currency Converter Estimates the historical value of the yen into other currencies

| Preceded by: Japanese mon |

Currency of Japan 1870 – |

Succeeded by: Current |