Islam in Russia

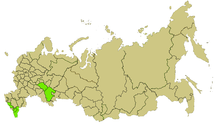

Islam in Russia is the nation's second most widely professed religion. According to US Department of State in 2017,[2] Muslims in Russia numbered 14,220,000 or 10% of the total population. According to a comprehensive survey in conducted in 2012, Muslims were 6.5% of the Russia's population.[3][4] However, the populations of two federal subjects with Islamic majorities were not surveyed due to social unrest, which together had a population of nearly 2 million, namely Chechnya and Ingushetia,[3] thus the total number of Muslims may be slightly larger. Among these Muslims, 6,700,000 or 4.6% of the total population of Russia were not affiliated with any Islamic schools and branches.

Recognized under the law and by Russian political leaders as one of Russia's traditional religions, Islam is a part of Russian historical heritage, and is subsidized by the Russian government.[5] The position of Islam as a major Russian religion, alongside Orthodox Christianity, dates from the time of Catherine the Great, who sponsored Islamic clerics and scholarship through the Orenburg Assembly.[6]

The history of Islam and Russia encompasses periods of conflict between the Muslim minority and the Orthodox majority, as well as periods of collaboration and mutual support. Robert Crews's study of Muslims living under the Tsar indicates that "the mass of Muslims" was loyal to that regime after Catherine, and sided with it over its Ottoman rival.[7] After the Tsarist regime fell, the Soviet Union introduced a policy of state atheism, which impeded the practice of Islam and other religions and led to the execution and suppression of various Muslim leaders. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Islam regained a prestigious, legally recognized space in Russian politics. More recently, President Putin consolidated this trend, subsidizing the creation of mosques and Islamic education, which he called an "integral part of Russia's cultural code",[8] encouraging immigration from Muslim-majority former Soviet bloc states, and condemning what the Russian state considers to be criminal anti-Muslim hate speech, such as caricatures of the Muhammad.[9]

Muslims form a majority of the population of the republics of Bashkortostan and Tatarstan in the Volga Federal District, and predominate among the nationalities in the North Caucasian Federal District located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea: the Circassians, Balkars, Chechens, Ingush, Kabardin, Karachay, and numerous Dagestani peoples. Also, in the middle of the Volga Region reside populations of Tatars and Bashkirs, the vast majority of whom are Muslims. Other areas with notable Muslim minorities include Moscow, Saint Petersburg, the republics of Adygea, North Ossetia-Alania and Astrakhan, Moscow, Orenburg and Ulyanovsk oblasts. There are over 5,000 registered religious Muslim organizations,[10] equivalent to over one sixth of the number of registered Russian Orthodox religious organizations of about 29,268 as of December 2006.[11]

Islam in Russia by region

Percentage of Muslims in Russia by region:

History of Islam in Russia

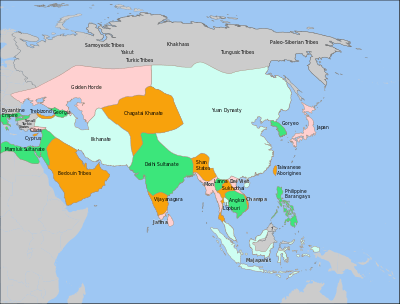

In the mid 7th century AD, as part of the Muslim conquest of Persia, Islam penetrated into the Caucasus region, parts of which were later permanently incorporated by Russia.[12] The first people to become Muslims within current Russian territory, the Dagestani people (region of Derbent), converted after the Arab conquest of the region in the 8th century. The first Muslim state in the future Russia lands was Volga Bulgaria[13] (922). The Tatars of the Khanate of Kazan inherited the population of believers from that state. Later most of the European and Caucasian Turkic peoples also became followers of Islam.[14]

The Tatars of the Crimean Khanate, the last remaining successor to the Golden Horde, continued to raid Southern Russia and burnt down parts of Moscow in 1571.[15] Until the late 18th century, Crimean Tatars maintained a massive slave-trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East, exporting about 2 million slaves from Russia and Ukraine over the period 1500–1700.[16]

From the early 16th-century up to including the course of the 19th century, all of Transcaucasia and southern Dagestan was ruled by various successive Iranian empires (the Safavids, Afsharids, and the Qajars), and their geo-political and ideological neighbouring arch-rivals on the other hand, the Ottoman Turks. In the respective areas they ruled, in both the North Caucasus and South Caucasus, Shia Islam and Sunni Islam spread, resulting in a fast and steady conversion of many more ethnic Caucasian peoples in adjacent territories.

The period from the Russian conquest of Kazan in 1552 by Ivan the Terrible to the ascension of Catherine the Great in 1762 featured systematic Russian repression of Muslims through policies of exclusion and discrimination - as well as the destruction of Muslim culture by the elimination of outward manifestations of Islam such as mosques.[17] The Russians initially demonstrated a willingness in allowing Islam to flourish as Muslim clerics were invited into the various regions to preach to the Muslims, particularly the Kazakhs, whom the Russians viewed with contempt.[18][19] However, Russian policy shifted toward weakening Islam by introducing pre-Islamic elements of collective consciousness.[20] Such attempts included methods of eulogizing pre-Islamic historical figures and imposing a sense of inferiority by sending Kazakhs to highly élite Russian military institutions.[20] In response, Kazakh religious leaders attempted to bring religious fervor by espousing pan-Turkism, though many were persecuted as a result.[21] The government of Russia paid Islamic scholars from the Ural-Volga area working among the Kazakhs[22]

Islamic slavery did not have racial restrictions. Russian girls were legally allowed to be sold in Russian controlled Novgorod to Tatars from Kazan in the 1600s by Russian law. Germans, Poles, and Lithuanians were allowed to be sold to Crimean Tatars in Moscow. In 1665 Tatars were allowed to buy from the Russians, Polish and Lithuanian slaves. Before 1649 Russians could be sold to Muslims under Russian law in Moscow. This contrasted with other places in Europe outside Russia where Muslims were not allowed to own Christians.[23]

The Cossack institution recruited and incorporated Muslim Mishar Tatars.[24] Cossack rank was awarded to Bashkirs.[25] Muslim Turkics and Buddhist Kalmyks served as Cossacks. The Cossack Ural, Terek, Astrakhan, and Don Cossack hosts had Kalmyks in their ranks. Mishar Muslims, Teptiar Muslims, service Tatar Muslims, and Bashkir Muslims joined the Orenburg Cossack Host.[26] Cossack non-Muslims shared the same status with Cossack Siberian Muslims.[27] Muslim Cossacks in Siberia requested an Imam.[28] Cossacks in Siberia included Tatar Muslims like in Bashkiria.[29]

Bashkirs and Kalmyks in the Russian military fought against Napoleon's forces.[30][31] They were judged suitable for inundating opponents but not intense fighting.[32] They were in a non-standard capacity in the military.[33] Arrows, bows, and melee combat weapons were wielded by the Muslim Bashkirs. Bashkir women fought among the regiments.[34] Denis Davidov mentioned the arrows and bows wielded by the Bashkirs.[35][36] Napoleon's forces faced off against Kalmyks on horseback.[37] Napoleon faced light mounted Bashkir forces.[38] Mounted Kalmyks and Bashkirs numbering 100 were available to Russian commandants during the war against Napoleon.[39] Kalmyks and Bashkirs served in the Russian army in France.[40] A nachalnik was present in every one of the 11 cantons of the Bashkir host which was created by Russia after the Pugachev Rebellion.[41] Bashkirs had the military statute of 1874 applied to them.[42]

While total expulsion (as practised in other Christian nations such as Spain, Portugal and Sicily) was not feasible to achieve a homogeneous Russian-Orthodox population, other policies such as land grants and the promotion of migration by other Russian and non-Muslim populations into Muslim lands displaced many Muslims, making them minorities in places such as some parts of the South Ural region and encouraging emigration to other parts such as the Ottoman Turkey and neighboring Persia, and almost annihilating the Circassians, Crimean Tatars, and various Muslims of the Caucasus. The Russian army rounded up people, driving Muslims from their villages to ports on the Black Sea, where they awaited ships provided by the neighboring Ottoman Empire. The explicit Russian goal involved expelling the groups in question from their lands.[43] They were given a choice as to where to be resettled: in the Ottoman Empire, in Persia, or in Russia far from their old lands. The Russo-Caucasian War ended with the signing of loyalty oaths by Circassian leaders on 2 June [O.S. 21 May] 1864. Afterwards, the Ottoman Empire offered to harbour the Circassians who did not wish to accept the rule of a Christian monarch, and many emigrated to Anatolia (the heart of the Ottoman Empire) and ended up in modern Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Iraq and Kosovo. Many other Caucasian Muslims ended up in neighboring Iran - sizeable numbers of Shia Lezgins, Azerbaijanis, Muslim Georgians, Kabardins, and Laks.[44] Various Russian, Caucasus, and Western historians agree on the figure of c. 500,000 inhabitants of the highland Caucasus being deported by Russia in the 1860s. A large proportion of them died in transit from disease. Those that remained loyal to Russia were settled into the lowlands, on the left-bank of the Kuban' River. The trend of Russification has continued at different paces in the rest of Tsarist and Soviet periods, so that as of 2014 more Tatars lived outside the Republic of Tatarstan than inside it.[14]

A policy of deliberately enforcing anti-modern, traditional, ancient conservative Islamic education in schools and Islamic ideology was enforced by the Russians in order to deliberately hamper and destroy opposition to their rule by keeping them in a state of torpor to and prevent foreign ideologies from penetrating in.[45][46]

Communist rule oppressed and suppressed Islam, like other religions in the Soviet Union. Many mosques (for some estimates,[47] more than 83% in Tatarstan) were closed. For example, the Märcani Mosque was the only acting mosque in Kazan at that time.

Islam in the post-Soviet period

There was much evidence of official conciliation toward Islam in Russia in the 1990s. The number of Muslims allowed to make pilgrimages to Mecca increased sharply after the embargo of the Soviet era ended in 1991.[48] In 1995 the newly established Union of Muslims of Russia, led by Imam Khatyb Mukaddas of Tatarstan, began organizing a movement aimed at improving inter-ethnic understanding and ending Russians' lingering misconception of Islam. The Union of Muslims of Russia is the direct successor to the pre-World War I Union of Muslims, which had its own faction in the Russian Duma. The post-Communist union formed a political party, the Nur All-Russia Muslim Public Movement, which acts in close coordination with Muslim imams to defend the political, economic, and cultural rights of Muslims. The Islamic Cultural Center of Russia, which includes a madrassa (religious school), opened in Moscow in 1991. In the 1990s, the number of Islamic publications has increased. Among them are few magazines in Russian, namely: "Ислам" (transliteration: Islam), "Эхо Кавказа" (Ekho Kavkaza) and "Исламский вестник" (Islamsky Vestnik), and the Russian-language newspaper "Ассалам" (Assalam), and "Нуруль Ислам" (Nurul Islam), which are published in Makhachkala, Dagestan.

Kazan has a large Muslim population (probably the second after Moscow urban group of the Muslims and the biggest indigenous group in Russia) and is home to the Russian Islamic University in Kazan, Tatarstan. Education is in Russian and Tatar. In Dagestan there are number of Islamic Universities and madrassas, notable among them are: Dagestan Islamic University, Institute of Theology and International Relations, whose rector Maksud Sadikov was assassinated on 8 June 2011.[49]

Talgat Tadzhuddin was the Chief Mufti of Russia. Since Soviet times, the Russian government has divided Russia into a number of Muslim Spiritual Directorates. In 1980 Talgat Tazhuddin was made Mufti of the European USSR and Siberia Division. Since 1992 he has headed the central or combined Muslim Spiritual Directorate of all of Russia.

Putin has said that Orthodox Christianity is much closer to Islam than Catholicism is.[50][51][52][53]

There was large anger from mostly Muslims from the Caucasus against the Charlie Hebdo cartoons in France.[54] Putin is believed to have backed protests by Muslims in Russia against Charlie Hebdo cartoons and the West.[55]

Putin has allowed the de facto implementation of Sharia law in Chechnya by Ramzan Kadyrov, including polygamy and enforced veiling.[56]

_12.jpg)

A chain e-mail spread a hoax speech attributed to Putin which called for tough assimilation policies on immigrants, no evidence of any such speech can be found in Russian media or Duma archives.[57][58][59][60]

Islam has been expanding under Putin's rule.[61] Tatar Muslims are engaging in a revival under Putin.[62]

A Muslim Tatar owned supermarket in Tatarstan sold calendars with images of American President Obama depicted as a monkey and initially refused to apologize for selling the calendar.[63][64] They were then forced to issue an apology later.[65]

In Tatarstan a Muslim Tatar staffed ice cream factory produced Obamka (little Obama) ice cream with packaging showing an earring wearing black child and staff members like director of finance Anatoli Ragimkhanov and Rasil Mustafin, deputy development director defended the sale.[66][67][68][69] According to The Washington Post, "Russian Muslims are split regarding the [Russian] intervention in Syria, but more are pro- than anti-war."[70]

Demographics

The majority of Muslims in Russia adhere to the Sunni branch of Islam. About 10% or more than two million are Shia Muslims.[71] There is also an active presence of Ahmadis.[72] In a few areas, notably Dagestan and Chechnya, there is a tradition of Sunni Sufism, which is represented by Naqshbandi and Shadhili schools, whose spiritual master Said Afandi al-Chirkawi received hundreds of visitors daily.[73] The Azeris have also historically and still currently been nominally followers of Shi'a Islam, as their republic split off from the Soviet Union, significant number of Azeris immigrated to Russia in search of work.

The Muslim community in Russia continues to grow, having reached 25 million, according to the grand mufti of Russia, Sheikh Rawil Gaynetdin.[4]

Notable Russian converts to Islam include Vyacheslav Polosin,[74] Vladimir Khodov and Alexander Litvinenko, a defector from Russian intelligence, who converted on his deathbed.[75][76]

Hajj

A record 18,000 Russian Muslim pilgrims from all over the country attended the Hajj in Mecca, Saudi Arabia in 2006.[77] In 2010, at least 20,000 Russian Muslim pilgrims attended the Hajj, as Russian Muslim leaders sent letters to the King of Saudi Arabia requesting that the Saudi visa quota be raised to at least 25,000–28,000 visas for Muslims.[78] Due to overwhelming demand from Russian Muslims, on 5 July 2011, Muftis requested President Dmitry Medvedev's assistance in increasing the allocated by Saudi Arabia pilgrimage quota in Vladikavkaz.[79] The III International Conference on Hajj Management attended by some 170 delegates from 12 counties was held in Kazan from 7 – 9 July 2011.[80]

Language controversies

For centuries, the Tatars constituted the only Muslim ethnic group in European Russia, with Tatar language being the only language used in their mosques, a situation which saw rapid change over the course of the 20th century as a large number of Caucasian and central Asian Muslims migrated to central Russian cities and began attending Tatar-speaking mosques, generating pressure on the imams of such mosques to begin using Russian.[81][82] This problem is evident even within Tatarstan itself, where Tatars constitute a majority.[83]

Islam in Moscow

According to the 2010 Russian census, Moscow has less than 300,000 permanent residents of Muslim background, while some estimates suggest that Moscow has around 1 million Muslim residents and up to 1.5 million more Muslim migrant workers.[84] The city has permitted the existence of four mosques.[85][86] The mayor of Moscow claims that four mosques are sufficient for the population.[87] The city's economy "could not manage without them," he said. There are currently 4 mosques in Moscow,[88] and 8,000 in the whole Russia.[89]

Public perception of Muslims

Survey published in 2019 by the Pew Research Center found that 76% of Russians had a favourable view of Muslims, whereas 19% had an unfavourable view.[90]

Gallery

Tatar mosque in Irkutsk, Siberia, 1906

Tatar mosque in Irkutsk, Siberia, 1906 Mosque in Noyabrsk in Siberia's Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, where Muslims make up 18% of the total population.

Mosque in Noyabrsk in Siberia's Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, where Muslims make up 18% of the total population.

Central mosque of Karachaevsk, Karachaevo-Cherkessia

Central mosque of Karachaevsk, Karachaevo-Cherkessia

- Qolşärif Mosque, Kazan, Tatarstan

See also

- Islam by country

- Islam in the Soviet Union

- Islam in Tatarstan

- Islamic terrorism in Russia

- List of mosques in Russia

- Jadid

- Persecution of Muslims in Russia

- Religion in Russia

- History of Islam in the Arctic and Subarctic regions

References

- "Arctic mosque stays open but Muslim numbers shrink". 15 April 2007 – via Reuters.

- "RUSSIA 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT" (PDF).

- "Арена: Атлас религий и национальностей" [Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities] (PDF). Среда (Sreda). 2012. See also the results' main interactive mapping and the static mappings: "Religions in Russia by federal subject" (Map). Ogonek. 34 (5243). 27 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. The Sreda Arena Atlas was realised in cooperation with the All-Russia Population Census 2010 (Всероссийской переписи населения 2010), the Russian Ministry of Justice (Минюста РФ), the Public Opinion Foundation (Фонда Общественного Мнения) and presented among others by the Analytical Department of the Synodal Information Department of the Russian Orthodox Church. See: "Проект АРЕНА: Атлас религий и национальностей" [Project ARENA: Atlas of religions and nationalities]. Russian Journal. 10 December 2012.

- "Islam in Russia". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- Bell, I (2002). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. ISBN 978-1-85743-137-7. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Azamatov, Danil D. (1998), "The Muftis of the Orenburg Spiritual Assembly in the 18th and 19th Centuries: The Struggle for Power in Russia's Muslim Institution", in Anke von Kugelgen; Michael Kemper; Allen J. Frank, Muslim culture in Russia and Central Asia from the 18th to the early 20th centuries, vol. 2: Inter-Regional and Inter-Ethnic Relations, Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, pp. 355–384,

- Robert D. Crews, For Prophet and Tsar, pp. 299-300 (Harvard, 2006)

- http://www.newsweek.com/putin-pledges-support-islamic-schools-russia-791561

- https://www.tabletmag.com/scroll/188502/why-russia-is-no-place-to-be-charlie

- Page, Jeremy (2005-08-05). "The rise of Russian Muslims worries Orthodox Church". The Times. London. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- Сведения о религиозных организациях, зарегистрированных в Российской ФедерацииПо данным Федеральной регистрационной службы, декабрь 2006 (in Russian)

- Hunter, Shireen; et al. (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M.E. Sharpe. p. 3.

(..) It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam invaded early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab conquest of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.

-

Mako, Gerald (2011). "The Islamization of the Volga Bulghars: A Question Reconsidered". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. 18 (208). Retrieved 2015-10-07.

[...] the Volga Bulghars adopted the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam, as practised in Khwarazm.

- Shireen Tahmasseb Hunter, Jeffrey L. Thomas, Alexander Melikishvili, "Islam in Russia", M.E. Sharpe, Apr 1, 2004, ISBN 0-7656-1282-8

- Solovyov, S. (2001). History of Russia from the Earliest Times. 6. AST. pp. 751–809. ISBN 5-17-002142-9.

- Darjusz Kołodziejczyk, as reported by Mikhail Kizilov (2007). "Slaves, Money Lenders, and Prisoner Guards:The Jews and the Trade in Slaves and Captives in the Crimean Khanate". The Journal of Jewish Studies. p. 2.

- Frank, Allen J. Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780–1910. Vol. 35. Brill, 2001.

- Khodarkovsky, Michael. Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500-1800, pg. 39.

- Ember, Carol R. and Melvin Ember. Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures, pg. 572

- Hunter, Shireen. "Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security", pg. 14

- Farah, Caesar E. Islam: Beliefs and Observances, pg. 304

- Allen J. Frank (1998). Islamic Historiography and "Bulghar" Identity Among the Tatars and Bashkirs of Russia. BRILL. pp. 35–. ISBN 90-04-11021-6.

- KIZILOV, MIKHAIL (2007). "Slave Trade in the Early Modern Crimea From the Perspective of_Christian Muslim and Jewish Sources". Journal of Early Modern History. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. 11: 16.

- Allen J. Frank (1 January 2001). Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780-1910. BRILL. pp. 61–. ISBN 90-04-11975-2.

- Allen J. Frank (1 January 2001). Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780-1910. BRILL. pp. 79–. ISBN 90-04-11975-2.

- Allen J. Frank (1 January 2001). Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780-1910. BRILL. pp. 86–. ISBN 90-04-11975-2.

- Allen J. Frank (1 January 2001). Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780-1910. BRILL. pp. 87–. ISBN 90-04-11975-2.

- Allen J. Frank (1 January 2001). Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780-1910. BRILL. pp. 122–. ISBN 90-04-11975-2.

- Allen J. Frank (1 January 2001). Muslim Religious Institutions in Imperial Russia: The Islamic World of Novouzensk District and the Kazakh Inner Horde, 1780-1910. BRILL. pp. 170–. ISBN 90-04-11975-2.

- Vershinin, Alexander (29 July 2014). "How Russia's steppe warriors took on Napoleon's armies". Russia & India Report.

- John R. Elting (1997). Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée. Perseus Books Group. pp. 237–. ISBN 978-0-306-80757-2.

- Michael V. Leggiere (16 April 2015). Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany: Volume 2, The Defeat of Napoleon: The Franco-Prussian War of 1813. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-1-316-39309-3.Michael V. Leggiere (16 April 2015). Napoleon and the Struggle for Germany: 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-1-107-08054-6.

- Janet M. Hartley (2008). Russia, 1762–1825: Military Power, the State, and the People. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-275-97871-6.

- Nasirov, Ilshat (2005). "Islam in the Russian Army". Islam Magazine. Makhachkala.

- Alexander Mikaberidze (20 February 2015). Russian Eyewitness Accounts of the Campaign of 1807. Frontline Books. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-1-4738-5016-3.

- Denis Vasilʹevich Davydov (1999). In the Service of the Tsar Against Napoleon: The Memoirs of Denis Davidov, 1806–1814. Greenhill Books. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-85367-373-3.

- Andreas Kappeler (27 August 2014). The Russian Empire: A Multi-ethnic History. Routledge. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-317-56810-0.

- Tove H. Malloy; Francesco Palermo (8 October 2015). Minority Accommodation through Territorial and Non-Territorial Autonomy. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-106359-6.

- Dominic Lieven (15 April 2010). Russia Against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-42938-9.

- Dominic Lieven (15 April 2010). Russia Against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace. Penguin Publishing Group. pp. 504–. ISBN 978-1-101-42938-9.

- Bill Bowring (17 April 2013). Law, Rights and Ideology in Russia: Landmarks in the Destiny of a Great Power. Routledge. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-134-62580-2.

- Charles R. Steinwedel (9 May 2016). Threads of Empire: Loyalty and Tsarist Authority in Bashkiria, 1552–1917. Indiana University Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-253-01933-2.

- Kazemzadeh 1974

- А. Г. Булатова. Лакцы (XIX – нач. XX вв.). Историко-этнографические очерки. — Махачкала, 2000.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- Alexandre Bennigsen; Chantal Lemercier-Quelquejay; Central Asian Research Centre (London, England) (1967). Islam in the Soviet Union. Praeger. p. 15.

- А.Хабутдинов, Д.Мухетдинов. Ислам в СССР: предыстория репрессий Archived 2013-06-01 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "History of Hajj in Russia from 18th to 21st century - IslamDag.info".

- "IslamDag.info".

- "Window on Eurasia: Putin Says Orthodoxy 'Closer to Islam than Catholicism Is'".

- "Faith in expediency" – via The Economist.

- Nikolas K. Gvosdev; Christopher Marsh (22 August 2013). Russian Foreign Policy: Interests, Vectors, and Sectors. SAGE Publications. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-4833-2208-7.

- Илья Косыгин (4 January 2012). "Православие ближе к исламу, чем к католицизму. В. Путин" – via YouTube.

- Arkhipov, Ilya; Kravchenko, Stepan. "Putin Points Muslim Rage at Cold War Foes".

- "Chechnya declares public holiday to support huge anti-Charlie Hebdo rally". 20 January 2015.

- Julia Ioffe (24 July 2015). "Putin Is Down With Polygamy". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- "Fact Check: No record of Putin's speech on Muslims".

- Archives. "Russian President Vladimir Putin Says No to Sharia-Fiction!".

- Mikkelson, David. "Vladimir Putin's Speech to the Duma on Minorities".

- "Vladimir Putin's Supposed Speech to the Duma on Minorities and Sharia Law".

- Miller, Rebecca M. "Comeback: How Islam Got Its Groove Back in Russia".

- "Do minorities have a place in Putin's Russia?".

- "Russian Media Explodes With Vulgar and Racist Anti-Obama Rhetoric". 15 December 2015.

- "Russian supermarket under fire for selling 'monkey Obama' chopping board".

- Alan, Bike Timerova, Naif Akmal and Nail (10 December 2015). "Russian Chain Apologizes For Racist Obama Cutting Board" – via Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

- "Little Obama Ice Cream Goes on Sale in Russia's Tatarstan".

- "Obamka ice cream: Russians mock it on the web, US officials feel offended".

- "Without political inside information in Tatarstan began to produce ice cream "Obamka"".

- "Obama banana 'jokes' show Soviet-era racism remains alive in Russia". 12 May 2016 – via The Guardian.

- "Are Russia's 20 million Muslims seething about Putin bombing Syria?". The Washington Post. 7 March 2016.

- Goble, Paul. "Because of Syria, Moscow Focusing on Sunni-Shiite Divide Within Russia". Window on Eurasia -- New Series. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Ingvar Svanberg, David Westerlund. Islam Outside the Arab World. Routledge. p. 418. ISBN 0-7007-1124-4. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- "Shaykh Said Afandi al-Chirkawi - IslamDag.info".

- "IslamDag.info".

- "Litvinenko converted to Islam father says". The Times. London. 2006-12-08. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- "On The Road - British investigators land in Moscow".

- Russian Pilgrims Number Exceeds 18,000, Ministry of Hajj, Saudi Arabia.

- "Russian Muslims on Hajj to Saudi Arabia". 8 November 2010.

- "IslamDag.info".

- "IslamDag.info".

- "The Rebirth of Islam in Russia".

- "РЕЛИГАРЕ - "Русский ислам" как явление и как предмет исследования". www.religare.ru.

- http://www.allrussia.ru/pressreview/default.asp?id=37870&rub_id=19&VYear=2000&VMonth=4&VDay=18

- "Строители и гувернантки покидают Москву". Российская газета.

- Shuster, Simon (2 August 2013). "Underground Islam" – via Slate.

- "Russia's biggest mosque to be built in Moscow".

- "Moscow mayor: No more mosques in my city". 21 November 2013 – via Christian Science Monitor.

- http://www.rudaw.net/english/world/280820151

- "7500 Mosques Have Been Erected in Russia Since Putin Became President".

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism – 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

External links

- Kurbanov, Ruslan. Reasons and Consequences: Banning Hadiths and Seerah in Russia, onislam.net

- islam.ru (in English)

- History of Hajj in Russia from 18th to 21st century

- Why Islam?

- Akhmetova, Elmira. Islam in Russia (History & Facts), onislam.net

- Chris Kutschera - "The Rebirth of Islam in Tatarstan"

- Russian Islam goes its own way BBC

- Russian Islam Comes Out into the Open The Moscow News

- Russia has a Muslim dilemma Ethnic Russians hostile to Muslims

- Islam in Russia

- Russian mosques

- Moscow's Mosque Problem - slideshow by Der Spiegel

- Akhmetova, Elmira. Islam in the Volga Region, onislam.net

- Sotnichenko, Alexander Islam, Russian Orthodox Church Relations and the State in Post-communist Russia Politics and Religion Journal

- What is it like to be a Muslim in Russia?

- Central Muslim Spiritual Board of Russia - official website

- Russia Mufties Council - official website

.jpg)