Prayer rug

A prayer rug or prayer mat is a piece of fabric, sometimes a pile carpet, used by Muslims and some Christians during prayer.

In Islam, it placed between the ground and the worshipper for cleanliness during the various positions of Islamic prayer. These involve prostration and sitting on the ground. A Muslim must perform wudu (ablution) before prayer, and must pray in a clean place.

Prayer rugs are also used by some Oriental Orthodox Christians for Christian prayer involving prostrations in the name of the Trinity, as well as during the recitation of the Alleluia and Kyrie eleison.[1] Its purpose is to maintain a cleanly space to pray to God and shoes must be removed when using the prayer rug.[2] Among Russian Orthodox Old Ritualists, a special prayer rug known as the Podruchnik is used to keep one's face and hands clean during prostrations, as these parts of the body are used to make the sign of the cross.[3]

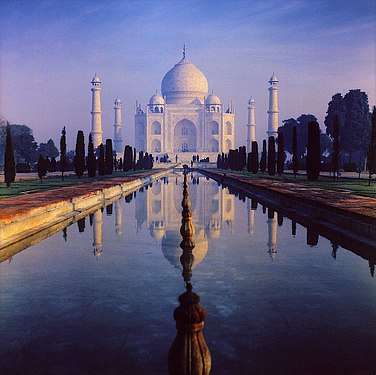

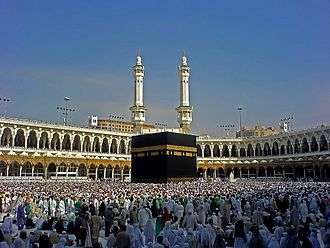

Many new prayer mats are manufactured by weavers in a factory. The design of a prayer mat is based on the village it came from and its weaver. These rugs are usually decorated with many beautiful geometric patterns and shapes. They are sometimes even decorated with images. These images are usually important Islamic landmarks, such as the Kaaba, but they are never animate objects.[4] This is because the drawing of animate objects on Islamic prayer mats is forbidden.

For Muslims, when praying, a niche, representing the mihrab of a mosque, at the top of the mat must be pointed to the Islamic center for prayer, Mecca. All Muslims are required to know the qibla or direction towards Mecca from their home or where they are while traveling.

History

Prayer rugs are used in some traditions of Oriental Orthodox Christianity and Western Orthodox Christianity, to provide a clean space for believers to offer Christian prayers to God; Oriental Orthodox Christians, such as the Copts, incorporate prostrations in their prayers, which are performed facing east towards Jerusalem, "prostrating three times in the name of the Trinity; at the end of each Psalm … while saying the ‘Alleluia’; and multiple times during the more than forty Kyrie eleisons" (cf. Agpeya).[1][2] These prayer rugs are often blessed by Christian clergy in the church before ever being used;[1] in this way, when a Christian prays at home, it is as if he is praying in his local church.[2] Additionally, carpets cover the floors of parishes in denominations such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church on which Christians prostrate in prayer.[5] Among Russian Orthodox Old Ritualists, a special prayer rug known as the Podruchnik is used to keep one's face and hands clean during prostrations, as these parts of the body are used to make the sign of the cross.[3] In the Middle East and South Asia, where Christian missionaries are engaged in evangelism, some converts to Christianity use prayer rugs for prayer and worship in order to preserve their Eastern cultural context.[6] In modern times, among most adherents of Western Christianity, kneelers placed in pews (for corporate worship) or in prie-dieus (for private worship) are customary; historically however, prayer rugs were used by some Christian monks to pray the canonical hours in places such as Syria, Northumbria, and Ireland well before the arrival of Islam.[7][8]

After the advent of Islam, Muslims often depicted the Kaaba in order to distinguish themselves from Christian carpets.[4]

In cases involving prisoners, legal rules have allowed Orthodox Christians and Muslims access to prayer rugs.[9]

Name variations

| Region/country | Language | Main |

|---|---|---|

| Arab World | Arabic | سجادة الصلاة (Sajjādat aṣ-ṣalāt), pl. سجاجيد الصلاة (Sajājīd aṣ-ṣalāt) |

| Greater Iran | Persian | جانماز (Jānamāz)[10] |

| South Asia | Hindi-Urdu | جائے نماز / जा-ए-नमाज़ (Já-e-namáz)[11] |

| Pashtunistan | Pashto | د لمانځه پوزی |

| Bengal, Assam | Bengali, Assamese | জায়নামাজ/জায়নামায (Jāynamāz) |

| Bosnia | Bosnian | sedžada, serdžada, postećija |

| Indonesia | Indonesian, Basa Jawa, Basa Sunda | Sajadah |

| Malaysia | Malay | Sejadah |

| Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania | Wolof | Sajadah |

| Nigeria, Niger, Ghana, Cameroon | Hausa | Buzu na salla, dadduma, darduma |

| South Kalimantan | Banjar | Pasahapan |

| Iraqi Kurdistan | Sorani | بەرماڵ |

| Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan | Kazakh, Kyrgyz | Жайнамаз (Jainamaz) |

| Uzbekistan | Uzbek | Joynamoz |

| Greater Somalia | Somali | sijayad, salli, Sajadat |

| Turkey, Azerbaijan | Turkish, Azeri | Seccade, namazlık |

| Turkmenistan | Turkmen | Namazlyk |

Features and use

The prayer rug has a very strong symbolic meaning and traditionally taken care of in a holy manner. It is disrespectful for one to place a prayer mat in a dirty location (as Muslims have to be clean to show their respect to God) or throw it around in a disrespectful manner. The prayer mat is traditionally woven with a rectangular design, typically made asymmetrical by the niche at the head end. Within the rectangle one usually finds images of Islamic symbols and architecture. In some cultures decorations not only are important but also have a deep sense of value in the design of the prayer rug.

A prayer rug is characterized by a niche at one end, representing the mihrab in every mosque, a directional point to direct the worshipper towards Mecca.[12] Many rugs also show one or more mosque lamps,[12] a reference to the Verse of Light in the Qur'an. Specific mosques are sometimes shown; some of the most popular examples include the mosques in Mecca, Medina, and especially Jerusalem. Decorations not only play a role in imagery but serve the worshipper as aids to memory. Some of the examples include a comb and pitcher, which is a reminder for Muslims to wash their hands and for men to comb their hair before performing prayer. Another important use for decorations is to aid newly converted Muslims by stitching decorative hands on the prayer mat where the hands should be placed when performing prayer.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

|

| Dress |

| Holidays |

|

| Literature |

|

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Prayer rugs are usually made in the towns or villages of the communities who use them and are often named after the origins of those who deal and collect them. The exact pattern will vary greatly by original weavers and the different materials used. Some may have patterns, dyes and materials that are traditional/native to the region in which they were made. Prayer rugs' patterns generally have a niche at the top, which is turned to face Mecca. During prayer the supplicant kneels at the base of the rug and places his or her hands at either side of the niche at the top of the rug, his or her forehead touching the niche. Typical prayer rug sizes are approximately 2.5 ft × 4 ft (0.76 m × 1.22 m) - 4 ft × 6 ft (1.2 m × 1.8 m), enough to kneel above the fringe on one end and bend down and place the head on the other.

Some countries produce textiles with prayer rug patterns for export. Many modern prayer rugs are strictly commercial pieces made in large numbers to sell on an international market or tourist trade.

There are many prayer rugs in existence today that have been taken care of for more than 100 years.[13] In most cases, they have been immediately and carefully rolled after each prayer.

The Transylvanian miracle: Islamic rugs in Protestant Churches

The Saxon Lutheran Churches, parish storerooms and museums of Transylvania safeguard about four hundred Anatolian rugs, dating from the late-15th to the mid-18th century. They form the richest and best-preserved corpus of prayer-format rugs of Ottoman period outside Turkey.

Without attempting a résumé of the region's complex history, Transylvania (like the other Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia) never came under direct Turkish occupation. Until 1699 it had the status of an autonomous Principality, maintaining the Christian religion and own administration but paying tribute to the Ottoman Porte. By contrast, following the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, part of Hungary was designated a Pashalik and was under Turkish occupation for over a century and a half.

Rugs came into the ownership of the Reformed Churches, mainly as pious donations from parishioners, benefactors or guilds. In the 16th century, with the coming of the Reformation, the number of figurative images inside the churches was drastically reduced as people followed the ten commandments earnestly: "You shall not make for yourself a carved image..., you shall not bow down to them or serve them". Frescoes were white-washed or destroyed, and the many sumptuous winged altar-pieces were removed maintaining exclusively the main altar piece. The recently converted parishioners thus perceived the church as a large, cold and empty space that needed warming up and a welcoming touch. Traces of the mural decoration were found during modern restorations in some Protestant Churches as for instance at Malâncrav.

In this situation the Oriental rugs, created in a world that was spiritually different from Christianity, found their place in the Reformed churches which were to become their main custodians. The removal from the commercial circuit and the fact that they were used to decorate the walls, the pews and the balconies but not on the floor was crucial for their conservation over the years. This is unique and quite extraordinary if we consider that the Ottoman Empire heavily dominated the region at that time. This fact confirms not only the traditional religious tolerance of Transylvanians but also the capacity of Oriental rugs to bridge different cultures.

Gallery

Typical manufactured prayer mat showing the Kaaba

Typical manufactured prayer mat showing the Kaaba Early 20th-century Siirt Battaniyesi. Child's mohair prayer rug/blanket

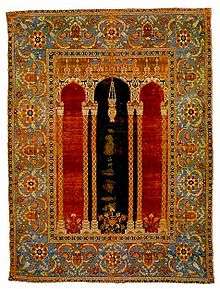

Early 20th-century Siirt Battaniyesi. Child's mohair prayer rug/blanket Ottoman Era Kayseri silk prayer rug. Circa 1880s

Ottoman Era Kayseri silk prayer rug. Circa 1880s Vintage Konya prayer seccade

Vintage Konya prayer seccade Antique Gaziantep double prayer rug

Antique Gaziantep double prayer rug Ancient Kirşehir prayer rug in the Tilavet room; Mevlâna Mausoleum, Konya

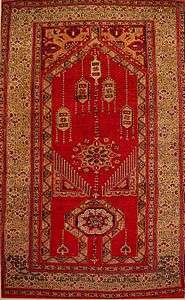

Ancient Kirşehir prayer rug in the Tilavet room; Mevlâna Mausoleum, Konya Turkish prayer rug

Turkish prayer rug Fachralo Kazak prayer rug, late 19th century

Fachralo Kazak prayer rug, late 19th century The James F. Ballard late 16th century Bursa prayer rug

The James F. Ballard late 16th century Bursa prayer rug Caucasian prayer rug, Shirvan

Caucasian prayer rug, Shirvan Umayyad Mosque prayer rug saph, Damascus

Umayyad Mosque prayer rug saph, Damascus Muslim prostrating on prayer rug. Artist Charles Bargue

Muslim prostrating on prayer rug. Artist Charles Bargue The Sultan Ahmet Camii prayer rug saph, "The Blue Mosque", Istanbul

The Sultan Ahmet Camii prayer rug saph, "The Blue Mosque", Istanbul Vintage Balouch prayer rug

Vintage Balouch prayer rug Prayer rug Afghanistan

Prayer rug Afghanistan Antique Anatolian prayer rug

Antique Anatolian prayer rug "Re-entrant" or "keyhole" prayer mat, also called a Bellini carpet, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century. The mat symbolically describes the environment of a mosque, with the entrance (the "keyhole"), and the mihrab (the forward corner) with its hanging mosque lamps.

"Re-entrant" or "keyhole" prayer mat, also called a Bellini carpet, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century. The mat symbolically describes the environment of a mosque, with the entrance (the "keyhole"), and the mihrab (the forward corner) with its hanging mosque lamps.

Kayseri prayer rug, Anatolia Turkey

Kayseri prayer rug, Anatolia Turkey

See also

- Islamic art

- Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

- Persian embroidery

- Podruchnik, a cushion for worshipper's hands among Russian Old Believer Christians

- Tradition of removing shoes in the home and houses of worship

References

- Kosloski, Philip (16 October 2017). "Did you know Muslims pray in a similar way to some Christians?". Aleteia. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Bishop Brian J Kennedy, OSB. "Importance of the Prayer Rug". St. Finian Orthodox Abbey. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Basenkov, Vladimir (10 June 2017). "Vladimir Basenkov. Getting To Know the Old Believers: How We Pray". Orthodox Christianity. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Gantzhorn, Volkmar (1998). Oriental Carpets: Their Iconology and Iconography, from Earliest Times to the 18th Century. Taschen. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-8228-0545-9.

This Moslem prayer rug, too, shows the Kaaba in order to distinguish itself clearly from Christian carpets, whose Armenian border it kept.

- Duffner, Jordan Denari (13 February 2014). "Wait, I thought that was a Muslim thing?!". Commonweal. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Neff, David (19 May 1997). "Going to the Prayer Mat for Jesus". Christianity Today. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Diarmaid MacCulloch (2009). A History of Christianity. Penguin Group. p. 258.

- "Shwebo and his Monastery". Columban Interreligious Dialogue. 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Dinan, Elizabeth. "Inmate sues for return of prayer rug". USA Today Network. pp. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

Islam and Muslim state inmates are allowed a medallion, a prayer rug, a skull cap, a strand of prayer beads and unscented Halal soaps from an approved vendor. Native American state inmates are allowed to have one “native choker,” a beaded necklace with fetish, four feathers, a medicine bag with approved contents, a dream catcher and five bandanas which can be worn with a 3-inch fold “sweatband style.” The state DOC list says Jewish inmates are allowed a medallion, two yarmulkes, a prayer shawl of specific dimensions and either a set of phylacteries or a Tifillin bracelet.Rastafarian inmates are allowed a medallion, Russian Orthodox state inmates are allowed prayer rugs and cushions and inmates who practice Siddha yoga are allowed a set of prayer beads, a meditation mat and a medallion.

- https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/305440-i-throw-my-makeshift-jai-namaz-my-prayer-rug-on-the

- "जा-ए-नमाज़". Rekhta. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Dimand, Maurice S.; Mackie, Louise W.; Ellis, Charles Grant (1974). Prayer Rugs. Washington, DC: Textile Museum. pp. 11, 19.

- Carpets from the Islamic World, 1600-1800

- Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania, 2007

Further reading

- "prayer rug." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 23 Oct. 2008 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/474169/prayer-rug.

- Faid, Abbo Muhammed Samir. "Islam" All Experts. 16 Mar 2005. <https://web.archive.org/web/20100224195249/http://www.liu.edu/CWIS/CWP/library/workshop/citmla.htm>

External links

- The Islamic Place: Prayer Rugs

- Importance of the Prayer Rug by Bishop Brian J Kennedy, OSB - Holy Trinity Celtic Orthodox Church

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prayer rugs. |

.jpeg)