Islamic influences on Western art

Islamic influences on Western art refers to the influence of Islamic art, the artistic production in the Islamic world from the 8th to the 19th century, on Christian art. During this period, the frontier between Christendom and the Islamic world varied a lot resulting in some cases in exchanges of populations and of corresponding art practices and techniques. Furthermore, the two civilizations had regular relationships through diplomacy and trade that facilitated cultural exchanges. Islamic art covers a wide variety of media including calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts, textiles, ceramics, metalwork and glass, and refers to the art of Muslim countries in the Near East, Islamic Spain, and Northern Africa, though by no means always Muslim artists or craftsmen. Glass production, for example, remained a Jewish speciality throughout the period, and Christian art, as in Coptic Egypt continued, especially during the earlier centuries, keeping some contacts with Europe.

Islamic decorative arts were highly valued imports to Europe throughout the Middle Ages; largely because of unsuspected accidents of survival the majority of surviving examples are those that were in the possession of the church. In the early period, textiles were especially important, used for church vestments, shrouds, hangings and clothing for the elite. Islamic pottery of everyday quality was still preferred to European wares. Because decoration was mostly ornamental, or small hunting scenes and the like, and inscriptions were not understood, Islamic objects did not offend Christian sensibilities.[1]

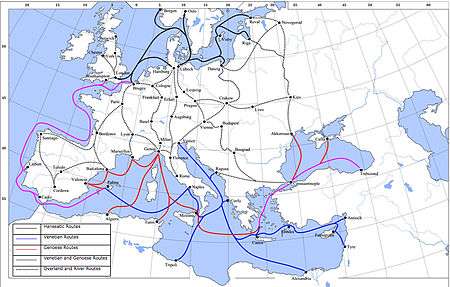

In the early centuries of Islam, the most important points of contact between the Latin West and the Islamic world from an artistic point of view were Southern Italy and Sicily and the Iberian peninsula, which both held significant Muslim populations. Later the Italian maritime republics were important in trading artworks. In the Crusades Islamic art seems to have had relatively little influence even on the Crusader art of the Crusader kingdoms, though it may have stimulated the desire for Islamic imports among Crusaders returning to Europe.

Numerous techniques from Islamic art formed the basis of art in the Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture of Norman Sicily, much of which used Muslim artists and craftsmen working in the style of their own tradition. Techniques included inlays in mosaics or metals, ivory carving or porphyry, sculpture of hard stones, and bronze foundries.[2] In Iberia the Mozarabic art and architecture of the Christian population living under Muslim rule remained very Christian in most ways, but showed Islamic influences in other respects; much what was described as this is now called Repoblación art and architecture. During the late centuries of the Reconquista Christian craftsmen started using Islamic artistic elements in their buildings, as a result the Mudéjar style was developed.

Middle Ages

Islamic art was widely imported and admired by European elites during the Middle Ages.[3] There was an early formative stage from 600-900 and the development of regional styles from 900 onwards. Early Islamic art used mosaic artists and sculptors trained in the Byzantine and Coptic traditions.[4] Instead of wall-paintings, Islamic art used painted tiles, from as early as 862-3 (at the Great Mosque of Kairouan in modern Tunisia), which also spread to Europe.[5] According to John Ruskin, the Doge's Palace in Venice contains "three elements in exactly equal proportions — the Roman, the Lombard, and Arab. It is the central building of the world. ... the history of Gothic architecture is the history of the refinement and spiritualization of Northern work under its influence".[6]

Islamic rulers controlled at various points parts of Southern Italy and most of modern Spain and Portugal, as well as the Balkans, all of which retained large Christian populations. The Christian Crusaders equally ruled Islamic populations. Crusader art is mainly a hybrid of Catholic and Byzantine styles, with little Islamic influence, but the Mozarabic art of Christians in Al Andaluz seems to show considerable influence from Islamic art, though the results are little like contemporary Islamic works. Islamic influence can also be traced in the mainstream of Western medieval art, for example in the Romanesque portal at Moissac in southern France, where it shows in both decorative elements, like the scalloped edges to the doorway, the circular decorations on the lintel above, and also in having Christ in Majesty surrounded by musicians, which was to become a common feature of Western heavenly scenes, and probably derives from images of Islamic kings on their diwan.[9] Calligraphy, ornament and the decorative arts generally were more important than in the West.[10]

The Hispano-Moresque pottery wares of Spain were first produced in Al-Andaluz, but Muslim potters then seem to have emigrated to the area of Christian Valencia, where they produced work that was exported to Christian elites across Europe;[11] other types of Islamic luxury goods, notably silk textiles and carpets, came from the generally wealthier[12] eastern Islamic world itself (the Islamic conduits to Europe west of the Nile were, however, not wealthier),[13] with many passing through Venice.[14] However, for the most part luxury products of the court culture such as silks, ivory, precious stones and jewels were imported to Europe only in an unfinished form and manufactured into the end product labelled as "eastern" by local medieval artisans.[15] They were free from depictions of religious scenes and normally decorated with ornament, which made them easy to accept in the West,[16] indeed by the late Middle Ages there was a fashion for pseudo-Kufic imitations of Arabic script used decoratively in Western art.

Decorative arts

A wide variety of portable objects from various decorative arts were imported from the Islamic world into Europe during the Middle Ages, mostly through Italy, and above all Venice.[17] In many areas European-made goods could not match the quality of Islamic or Byzantine work until near the end of the Middle Ages. Luxury textiles were widely used for clothing and hangings and also, fortunately for art history, also often as shrouds for the burials of important figures, which is how most surviving examples were preserved. In this area Byzantine silk was influenced by Sassanian textiles, and Islamic silk by both, so that is hard to say which culture's textiles had the greatest influence on the Cloth of St Gereon, a large tapestry which is the earliest and most important European imitation of Eastern work. European, especially Italian, cloth gradually caught up with the quality of Eastern imports, and adopted many elements of their designs.

Byzantine pottery was not produced in high-quality types, as the Byzantine elite used silver instead. Islam has many hadithic injunctions against eating off precious metal, and so developed many varieties of fine pottery for the elite, often influenced by the Chinese porcelain wares which had the highest status among the Islamic elites themselves — the Islamic only produced porcelain in the modern period. Much Islamic pottery was imported into Europe, dishes ("bacini") even in Islamic Al-Andalus in the 13th century, in Granada and Málaga, where much of the production was already exported to Christian countries. Many of the potters migrated to the area of Valencia, long reconquered by the Christians, and production here outstripped that of Al-Andaluz. Styles of decoration gradually became more influenced by Europe, and by the 15th century the Italians were also producing lustrewares, sometimes using Islamic shapes like the albarello.[18] Metalwork forms like the zoomorphic jugs called aquamanile and the bronze mortar were also introduced from the Islamic world.[19]

Mudéjar art in Spain

Mudéjar art is a style influenced by Islamic art that developed from the 12th century until the 16th century in the Iberia's Christian kingdoms. It is the consequence of the convivencia between the Muslim, Christian and Jewish populations in medieval Spain. The elaborate decoration typical of Mudéjar style fed into the development of the later Plateresque style in Spanish architecture, combining with late Gothic and Early Renaissance elements.

Pseudo-Kufic

The Arabic Kufic script was often imitated in the West during the Middle-Ages and the Renaissance, to produce what is known as pseudo-Kufic: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration".[20] Numerous cases of pseudo-Kufic are known in European religious art from around the 10th to the 15th century. Pseudo-Kufic would be used as writing or as decorative elements in textiles, religious halos or frames. Many are visible in the paintings of Giotto.[20]

Examples are known of the incorporation of Kufic script such as a 13th French Master Alpais' ciborium at the Louvre Museum.[N 1][21]

Architecture

Arab-Norman culture in Sicily

Christian buildings such as the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily, incorporated Islamic elements, probably usually created by local Muslim craftsmen working in their own traditions. The ceiling at the Cappella, with its wooden vault arches and gilded figurines, has close parallels with Islamic buildings in Fez and Fustat, and reflect the Muqarnas (stalactite) technique of emphasizing three-dimensional elements[22]

The diaphragm arch, Late Antique in origin, was widely used in Islamic architecture, and may have spread from Spain to France.[23]

"Saracen style"

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

Scholars of the 18–19th century, who generally preferred Classical art, disliked what they saw as the "disorder" of Gothic art and perceived similarities between Gothic and Islamic architecture. They often understated the case that Gothic art fully originated in the Islamic art of the Mosque, to the point of calling it "Saracenical". William John Hamilton commented on the Seljuks monuments in Konya: "The more I saw of this peculiar style, the more I became convinced that the Gothic was derived from it, with a certain mixture of Byzantine (...) the origin of this Gotho-Saracenic style may be traced to the manners and habits of the Saracens"[N 3][24] The 18th-century English historian Thomas Warton summarized:

"The marks which constitute the character of Gothic or Saracenical architecture, are, its numerous and prominent buttresses, its lofty spires and pinnacles, its large and ramified windows, its ornamental niches or canopies, its sculptured saints, the delicate lace-work of its fretted roofs, and the profusion of ornaments lavished indiscriminately over the whole building: but its peculiar distinguishing characteristics are, the small cluttered pillars and pointed arches, formed by the segments of two interfering circles"

Pointed arch

The pointed arch originated in the Byzantine and Sassanian empires, where it mostly appears in early churches in Syria. The Byzantine Karamagara Bridge has curved elliptical arches rising to a pointed keystone.[25] The priority of the Byzantines in its use is also evidenced by slightly pointed examples in Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, and the Hagia Irene, Constantinople.[25] The pointed arch was subsequently adopted and widely used by Muslim architects, becoming the characteristic arch of Islamic architecture.[25] According to Bony, it has spread from Islamic lands, possibly through Sicily, then under Islamic rule, and from there to Amalfi in Italy, before the end of the 11th century.[26][27] The pointed arch reduced architectural thrust by about 20% and therefore had practical advantages over the semi-circular Romanesque arch for the building of large structures.[26]

The pointed arch as a defining characteristic of Gothic architecture appears to have been introduced from the Islamic, in some areas, but to have evolved as a structural solution in late Romanesque, both in England at Durham Cathedral and in the Burgundian Romanesque and Cistercian architecture of France.[28]

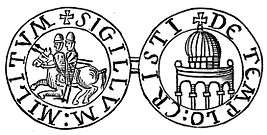

Templar churches

In 1119, the Knights Templar received as headquarters part of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, considered by the crusaders the Temple of Solomon, from which the order took its common name. The typical round churches built by the knights across Western Europe, such as the London Temple Church, are probably inspired by the shape of Al-Aqsa or the Dome of the Rock[29]

Islamic elements in Renaissance art

Pseudo-Kufic

Pseudo-Kufic is a decorative motif that resembles Kufic script and occurs in many Italian Renaissance paintings. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic in early Renaissance works is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13th–14th-century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them:[31] "In Renaissance art, pseudo-Kufic script was used to decorate the costumes of Old Testament heroes like David".[32] Mack states another hypothesis:

Perhaps they marked the imagery of a universal faith, an artistic intention consistent with the Church's contemporary international program.[33]

Oriental carpets

Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from the Ottoman Empire, the Levant or the Mamluk state of Egypt or Northern Africa, were used as important decorative features in paintings from the 13th century onwards, and especially in religious painting, starting from the Medieval period and continuing into the Renaissance period.[34]

Such carpets were often integrated into Christian imagery as symbols of luxury and status of Middle-Eastern origin, and together with Pseudo-Kufic script offer an interesting example of the integration of Eastern elements into European painting.[34]

Anatolian rugs were used in Transylvania as decoration in Evangelical churches.[35]

Islamic costumes

Islamic individuals and costumes often provided the contextual backdrop to describe an evangelical scene. This was particularly visible in a set of Venetian paintings in which contemporary Syrian, Palestinian, Egyptian and especially Mamluk personages are employed anachronistically in paintings describing Biblical situations.[36] An example in point is the 15th century The Arrest of St. Mark from the Synagogue by Giovanni di Niccolò Mansueti which accurately describes contemporary (15th century) Alexandrian Mamluks arresting Saint Mark in an historic scene of the 1st century CE.[36] Another case is Gentile Bellini's Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria.[37]

Ornament

A Western style of ornament based on the Islamic arabesque developed, beginning in late 15th century Venice; it has been called either moresque or western arabesque (a term with a complicated history). It has been used in a great variety of the decorative arts but has been especially long-lived in book design and bookbinding, where small motifs in this style have continued to be used by conservative book designers up to the present day. It is seen in gold tooling on covers, borders for illustrations, and printer's ornaments for decorating empty spaces on the page. In this field the technique of gold tooling had also arrived in the 15th century from the Islamic world, and indeed much of the leather itself was imported from there.[38]

Like other Renaissance ornament styles it was disseminated by ornament prints which were bought as patterns by craftsmen in a variety of trades. Peter Furhring, a leading specialist in the history of ornament, says that:

The ornament known as moresque in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (but now more commonly called arabesque) is characterized by bifurcated scrolls composed of branches forming interlaced foliage patterns. These basic motifs gave rise to numerous variants, for example, where the branches, generally of a linear character, were turned into straps or bands. ... It is characteristic of the moresque, which is essentially a surface ornament, that it is impossible to locate the pattern's beginning or end. ... Originating in the Middle East, they were introduced to continental Europe via Italy and Spain ... Italian examples of this ornament, which was often used for bookbindings and embroidery, are known from as early as the late fifteenth century.[39]

Elaborate book bindings with Islamic designs can be seen in religious paintings.[40] In Andrea Mantegna's Saint John the Baptist and Zeno, Saint John and Zeno hold exquisite books with covers displaying Mamluk-style center-pieces, of a type also used in contemporary Italian book-binding.[41]

See also

- Islamic influence on medieval Europe

Notes and references

Explanatory notes and item notices

- Muriel Barbier. "Master Alpais' ciborium – Master G. ALPAIS – Decorative Arts". Louvre museum website. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15.

- Ebers, Georg. "Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque." Volume 1. Cassell & Company, Limited: New York, 1878. p 213

- William John Hamilton (1842) Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia p.206

- Thomas Warton (1802), Essays on Gothic architecture p.14

Notes

- Mack 2001, pp. 3–8, and throughout

- Aubé 2006, pp. 164–165

- Hoffman, 324; Mack, Chapter 1, and passim throughout; The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711–1031), Metropolitan Museum of Art timeline Retrieved April 1, 2011

- Honour & Fleming 1982, pp. 256–262.

- Honour & Fleming 1982, p. 269.

- The Stones of Venice, chapter 1, paras 25 and 29; discussed pp. 49–56 here

- "CNG: Feature Auction CNG 70. SPAIN, Castile. Alfonso VIII. 1158-1214. AV Maravedi Alfonsi-Dobla (3.86 g, 4h). Toledo (Tulaitula) mint. Dated Safar era 1229 (1191 AD)". www.cngcoins.com. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- "Coin - Portugal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Beckwith 1964, pp. 206–209.

- Jones, Dalu & Michell, George, (eds); The Arts of Islam, Arts Council of Great Britain, 9, 1976, ISBN 0-7287-0081-6

- Caiger-Smith, chapters 6 & 7

- Hugh Thomas, An Unfinished History of the World, 224-226, 2nd edn. 1981, Pan Books, ISBN 0-330-26458-3; Braudel, Fernand, Civilization & Capitalism, 15-18th Centuries, Vol 1: The Structures of Everyday Life, William Collins & Sons, London 1981, p. 440: "If medieval Islam towered over the Old Continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific for centuries on end, it was because no state (Byzantium apart) could compete with its gold and silver money ..."; and Vol 3: The Perspective of the World, 1984, ISBN 0-00-216133-8, p. 106: "For them [the Italian maritime republics], success meant making contact with the rich regions of the Mediterranean - and obtaining gold currencies, the dinars of Egypt or Syria, ... In other words, Italy was still only a poor peripheral region ..." [period before the Crusades]. The Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD compiled by Angus Maddison show Iran and Iraq as having the world's highest per capita GDP in the year 1000

- Rather than along religious lines, the divide was between east and west, with the rich countries all lying east of the Nile: Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 382, table A.7. and Maddison, Angus (2007): "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 185, table 4.2 give 425 1990 International Dollars for Christian Western Europe, 430 for Islamic North Africa, 450 for Islamic Spain and 425 for Islamic Portugal, while only Islamic Egypt and the Christian Byzantine Empire had significantly higher GDP per capita than Western Europe (550 and 680–770 respectively) (Milanovic, Branko (2006): "An Estimate of Average Income and Inequality in Byzantium around Year 1000", Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 449–470 (468))

- The subject of Mack's book; the Introduction gives an overview

- Hoffman, Eva R. (2007): Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century, pp.324f., in: Hoffman, Eva R. (ed.): Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-5

- Mack, 4

- The subject of Mack's book; see Chapter 1 especially.

- Caiger-Smith, Chapters 6 and 7

- Jones & Michell 1976, p. 167

- Mack 2001, p. 51

- La Niece, McLeod & Rohrs 2010

- Kleinhenz & Barker 2004, p. 835

- Bony 1985, p. 306

- Schiffer 1999, p. 141

- Warren, John (1991), "Creswell's Use of the Theory of Dating by the Acuteness of the Pointed Arches in Early Muslim Architecture", Muqarnas, 8, pp. 59–65

- Bony 1985, p. 17

- Kleiner 2008, p. 342

- Bony 1985, p. 12

- God and Enchantment of Place: Reclaiming Human Experience, David Brown, Oxford University Press, 2004, page 203.

- Mack 2001, pp. 65–66

- Mack 2001, pp. 52, 69

- Freider. p.84

- Mack 2001, p. 69

- Mack 2001, pp. 73–93

- Ionescu, Stefano (2005). Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania (PDF) (1st ed.). Rome: Verduci Editore. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- Mack 2001, p. 161

- Mack 2001, pp. 164–65

- Harthan 1961, pp. 10–12

- Fuhring 1994, p. 162

- Mack 2001, pp. 125–37

- Mack 2001, pp. 127–28

References

- Aubé, Pierre (2006). Les empires normands d’Orient (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02297-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckwith, John (1964), Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-20019-X

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. California studies in the history of art. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05586-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuhring, Peter (1994). "Renaissance Ornament Prints; The French Contribution". In Jacobson, Karen (ed.). The French Renaissance in prints from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. (often wrongly cat. as George Baselitz). Grunwald Center, UCLA. ISBN 0-9628162-2-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grabar, Oleg (2006). Islamic visual culture, 1100 - 1800. Constructing the study of Islamic art. 2. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-86078-922-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harthan, John P. (1961). Bookbinding (2nd rev. ed.). HMSO (for the Victoria and Albert Museum). OCLC 220550025.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoffman, Eva R. (2007): Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century, in: Hoffman, Eva R. (ed.): Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-5

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (1982), "Honour", A World History of Art, London: Macmillan

- Jones, Dalu; Michell, George, eds. (1976). The Arts of Islam. Arts Council of Great Britain. ISBN 0-7287-0081-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2008). Gardner's art through the ages: the western perspective (13, revised ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-57355-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kleinhenz, Christopher; Barker, John W (2004). Medieval Italy : an encyclopedia, Volume 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93931-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- La Niece, Susan; McLeod, Bet; Rohrs, Stefan (2010). The Heritage of "Maitre Alpais": An International and Interdisciplinary Examination of Medieval Limoges Enamel and Associated Objects. British Museum Research Publication. ISBN 978-0-86159-182-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mack, Rosamond E. (2001). Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22131-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schiffer, Reinhold (1999). Oriental panorama: British travellers in 19th century Turkey. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-0407-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Caiger-Smith, Alan (1985). Lustre Pottery: Technique, Tradition and Innovation in Islam and the Western World. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-13507-2.

- Watkin, David (2005). A history of Western architecture (4 ed.). Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-459-9.

.jpeg)