Humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at the time. Today, the humanities are more frequently contrasted with natural, and sometimes social sciences, as well as professional training.[1]

The humanities use methods that are primarily critical, or speculative, and have a significant historical element[2]—as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences,[2] yet, unlike the sciences, it has no central discipline.[3] The humanities include the study of ancient and modern languages, literature, philosophy, history, archaeology, anthropology, human geography, law, politics, religion,[4] and art.

Scholars in the humanities are "humanity scholars" or humanists.[5] The term "humanist" also describes the philosophical position of humanism, which some "antihumanist" scholars in the humanities reject. The Renaissance scholars and artists were also called humanists. Some secondary schools offer humanities classes usually consisting of literature, global studies and art.

Human disciplines like history, folkloristics, and cultural anthropology study subject matters that the manipulative experimental method does not apply to—and instead mainly use the comparative method[6] and comparative research.

Fields

Anthropology

Anthropology is the holistic "science of humans", a science of the totality of human existence. The discipline deals with the integration of different aspects of the social sciences, humanities and human biology. In the twentieth century, academic disciplines have often been institutionally divided into three broad domains:

- The natural sciences seek to derive general laws through reproducible and verifiable experiments.

- The humanities generally study local traditions, through their history, literature, music, and arts, with an emphasis on understanding particular individuals, events, or eras.

- The social sciences have generally attempted to develop scientific methods to understand social phenomena in a generalizable way, though usually with methods distinct from those of the natural sciences.

The anthropological social sciences often develop nuanced descriptions rather than the general laws derived in physics or chemistry, or they may explain individual cases through more general principles, as in many fields of psychology. Anthropology (like some fields of history) does not easily fit into one of these categories, and different branches of anthropology draw on one or more of these domains.[7] Within the United States, anthropology is divided into four sub-fields: archaeology, physical or biological anthropology, anthropological linguistics, and cultural anthropology. It is an area that is offered at most undergraduate institutions. The word anthropos (άνθρωπος) is from the Greek word for "human being" or "person". Eric Wolf described sociocultural anthropology as "the most scientific of the humanities, and the most humanistic of the sciences".

The goal of anthropology is to provide a holistic account of humans and human nature. This means that, though anthropologists generally specialize in only one sub-field, they always keep in mind the biological, linguistic, historic and cultural aspects of any problem. Since anthropology arose as a science in Western societies that were complex and industrial, a major trend within anthropology has been a methodological drive to study peoples in societies with more simple social organization, sometimes called "primitive" in anthropological literature, but without any connotation of "inferior".[8] Today, anthropologists use terms such as "less complex" societies, or refer to specific modes of subsistence or production, such as "pastoralist" or "forager" or "horticulturalist", to discuss humans living in non-industrial, non-Western cultures, such people or folk (ethnos) remaining of great interest within anthropology.

The quest for holism leads most anthropologists to study a people in detail, using biogenetic, archaeological, and linguistic data alongside direct observation of contemporary customs.[9] In the 1990s and 2000s, calls for clarification of what constitutes a culture, of how an observer knows where his or her own culture ends and another begins, and other crucial topics in writing anthropology were heard. It is possible to view all human cultures as part of one large, evolving global culture. These dynamic relationships, between what can be observed on the ground, as opposed to what can be observed by compiling many local observations remain fundamental in any kind of anthropology, whether cultural, biological, linguistic or archaeological.[10]

Archaeology

Archaeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, and cultural landscapes. Archaeology can be considered both a social science and a branch of the humanities.[11] It has various goals, which range from understanding culture history to reconstructing past lifeways to documenting and explaining changes in human societies through time.

Archaeology is thought of as a branch of anthropology in the United States,[12] while in Europe, it is viewed as a discipline in its own right, or grouped under other related disciplines such as history.

Classics

Classics, in the Western academic tradition, refers to the studies of the cultures of classical antiquity, namely Ancient Greek and Latin and the Ancient Greek and Roman cultures. Classical studies is considered one of the cornerstones of the humanities; however, its popularity declined during the 20th century. Nevertheless, the influence of classical ideas on many humanities disciplines, such as philosophy and literature, remains strong.

History

History is systematically collected information about the past. When used as the name of a field of study, history refers to the study and interpretation of the record of humans, societies, institutions, and any topic that has changed over time.

Traditionally, the study of history has been considered a part of the humanities. In modern academia, history is occasionally classified as a social science.

Linguistics and languages

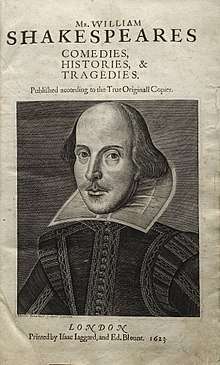

While the scientific study of language is known as linguistics and is generally considered a social science,[13] a natural science[14] or a cognitive science,[15] the study of languages is still central to the humanities. A good deal of twentieth-century and twenty-first-century philosophy has been devoted to the analysis of language and to the question of whether, as Wittgenstein claimed, many of our philosophical confusions derive from the vocabulary we use; literary theory has explored the rhetorical, associative, and ordering features of language; and historical linguists have studied the development of languages across time. Literature, covering a variety of uses of language including prose forms (such as the novel), poetry and drama, also lies at the heart of the modern humanities curriculum. College-level programs in a foreign language usually include study of important works of the literature in that language, as well as the language itself.

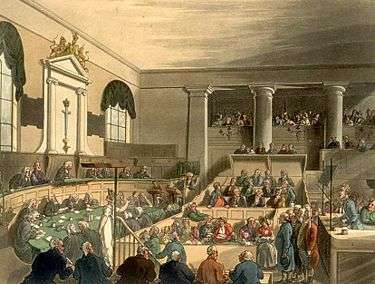

Law and politics

In common parlance, law means a rule that (unlike a rule of ethics) is enforceable through institutions.[16] The study of law crosses the boundaries between the social sciences and humanities, depending on one's view of research into its objectives and effects. Law is not always enforceable, especially in the international relations context. It has been defined as a "system of rules",[17] as an "interpretive concept"[18] to achieve justice, as an "authority"[19] to mediate people's interests, and even as "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction".[20] However one likes to think of law, it is a completely central social institution. Legal policy incorporates the practical manifestation of thinking from almost every social science and discipline of the humanities. Laws are politics, because politicians create them. Law is philosophy, because moral and ethical persuasions shape their ideas. Law tells many of history's stories, because statutes, case law and codifications build up over time. And law is economics, because any rule about contract, tort, property law, labour law, company law and many more can have long-lasting effects on how productivity is organised and the distribution of wealth. The noun law derives from the late Old English lagu, meaning something laid down or fixed,[21] and the adjective legal comes from the Latin word LEX.[22]

Literature

Literature is a term that does not have a universally accepted definition, but which has variably included all written work; writing that possesses literary merit; and language that foregrounds literariness, as opposed to ordinary language. Etymologically the term derives from Latin literatura/litteratura "writing formed with letters", although some definitions include spoken or sung texts. Literature can be classified according to whether it is fiction or non-fiction, and whether it is poetry or prose; it can be further distinguished according to major forms such as the novel, short story or drama; and works are often categorised according to historical periods, or according to their adherence to certain aesthetic features or expectations (genre).

Philosophy

Philosophy—etymologically, the "love of wisdom"—is generally the study of problems concerning matters such as existence, knowledge, justification, truth, justice, right and wrong, beauty, validity, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing these issues by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on reasoned argument, rather than experiments (experimental philosophy being an exception).[23]

Philosophy used to be a very comprehensive term, including what have subsequently become separate disciplines, such as physics. (As Immanuel Kant noted, "Ancient Greek philosophy was divided into three sciences: physics, ethics, and logic.")[24] Today, the main fields of philosophy are logic, ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology. Still, it continues to overlap with other disciplines. The field of semantics, for example, brings philosophy into contact with linguistics.

Since the early twentieth century, philosophy in English-speaking universities has moved away from the humanities and closer to the formal sciences, becoming much more analytic. Analytic philosophy is marked by emphasis on the use of logic and formal methods of reasoning, conceptual analysis, and the use of symbolic and/or mathematical logic, as contrasted with the Continental style of philosophy.[25] This method of inquiry is largely indebted to the work of philosophers such as Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Religion

Humans are inherently religious. At present, we do not know of any people or tribe, either from history or the present day, which may be said altogether devoid of “religion.” Religion may be characterized with a community since humans are social animals.[26][27] Rituals are used to bound the community together.[28] [29] Social animals require rules. Ethics is a requirement of society, but not a requirement of religion. Shinto, Daoism, and other folk or natural religions do not have ethical codes. The supernatural may or may not include deities since not all religions have deities (Theravada Buddhism and Daoism). Religion may have belief, but religions are not belief system.[30] Belief systems imply a logical model that religions do not display because of their internal contradictions, lack of evidence, falsehoods, and a faith element. Magical thinking creates explanations not available for empirical verification. Stories or myths are narratives being both didactic and entertaining.[31] They are necessary for understanding the human predicament. Some other possible characteristics of religion are pollutions and purification,[32] the sacred and the profane,[33] sacred texts,[34] religious institutions and organizations,[35][36] and sacrifice and prayer. Some of the major problems that religions confront, and attempts to answer are chaos, suffering, evil,[37] and death.[38]

The non-founder religions are Hinduism, Shinto, and native or folk religions. Founder religions are Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Confucianism, Daoism, Mormonism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and the Baha’i faith. Religions must adapt and changed through the generations because they must remain relevant to the adherents. When traditional religions fail to address new concerns, then new religions will emerge.

The humanities uses various mediums attempting to articulate the human predicament and prescribe meanings to the human situation. They are products of the human imagination. They are not discovered or invented but created. If creations characterize the humanities, then religion is the greatest creation of humankind.

Performing arts

The performing arts differ from the visual arts in so far as the former uses the artist's own body, face, and presence as a medium, and the latter uses materials such as clay, metal, or paint, which can be molded or transformed to create some art object. Performing arts include acrobatics, busking, comedy, dance, film, magic, music, opera, juggling, marching arts, such as brass bands, and theatre.

Artists who participate in these arts in front of an audience are called performers, including actors, comedians, dancers, musicians, and singers. Performing arts are also supported by workers in related fields, such as songwriting and stagecraft. Performers often adapt their appearance, such as with costumes and stage makeup, etc. There is also a specialized form of fine art in which the artists perform their work live to an audience. This is called Performance art. Most performance art also involves some form of plastic art, perhaps in the creation of props. Dance was often referred to as a plastic art during the Modern dance era.

Musicology

Musicology as an academic discipline can take a number of different paths, including historical musicology, music literature, ethnomusicology and music theory. Undergraduate music majors generally take courses in all of these areas, while graduate students focus on a particular path. In the liberal arts tradition, musicology is also used to broaden skills of non-musicians by teaching skills such as concentration and listening.

Theatre

Theatre (or theater) (Greek "theatron", θέατρον) is the branch of the performing arts concerned with acting out stories in front of an audience using combinations of speech, gesture, music, dance, sound and spectacle — indeed any one or more elements of the other performing arts. In addition to the standard narrative dialogue style, theatre takes such forms as opera, ballet, mime, kabuki, classical Indian dance, Chinese opera, mummers' plays, and pantomime.

Dance

Dance (from Old French dancier, perhaps from Frankish) generally refers to human movement either used as a form of expression or presented in a social, spiritual or performance setting. Dance is also used to describe methods of non-verbal communication (see body language) between humans or animals (bee dance, mating dance), and motion in inanimate objects (the leaves danced in the wind). Choreography is the art of creating dances, and the person who does this is called a choreographer.

Definitions of what constitutes dance are dependent on social, cultural, aesthetic, artistic, and moral constraints and range from functional movement (such as Folk dance) to codified, virtuoso techniques such as ballet.

Visual arts

History of visual arts

The great traditions in art have a foundation in the art of one of the ancient civilizations, such as Ancient Japan, Greece and Rome, China, India, Greater Nepal, Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica.

Ancient Greek art saw a veneration of the human physical form and the development of equivalent skills to show musculature, poise, beauty and anatomically correct proportions. Ancient Roman art depicted gods as idealized humans, shown with characteristic distinguishing features (e.g., Zeus' thunderbolt).

In Byzantine and Gothic art of the Middle Ages, the dominance of the church insisted on the expression of biblical and not material truths. The Renaissance saw the return to valuation of the material world, and this shift is reflected in art forms, which show the corporeality of the human body, and the three-dimensional reality of landscape.

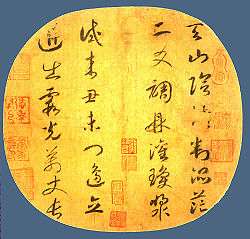

Eastern art has generally worked in a style akin to Western medieval art, namely a concentration on surface patterning and local colour (meaning the plain colour of an object, such as basic red for a red robe, rather than the modulations of that colour brought about by light, shade and reflection). A characteristic of this style is that the local colour is often defined by an outline (a contemporary equivalent is the cartoon). This is evident in, for example, the art of India, Tibet and Japan.

Religious Islamic art forbids iconography, and expresses religious ideas through geometry instead. The physical and rational certainties depicted by the 19th-century Enlightenment were shattered not only by new discoveries of relativity by Einstein[39] and of unseen psychology by Freud,[40] but also by unprecedented technological development. Increasing global interaction during this time saw an equivalent influence of other cultures into Western art.

Media types

Drawing

Drawing is a means of making a picture, using any of a wide variety of tools and techniques. It generally involves making marks on a surface by applying pressure from a tool, or moving a tool across a surface. Common tools are graphite pencils, pen and ink, inked brushes, wax color pencils, crayons, charcoals, pastels, and markers. Digital tools that simulate the effects of these are also used. The main techniques used in drawing are: line drawing, hatching, crosshatching, random hatching, scribbling, stippling, and blending. A computer aided designer who excels in technical drawing is referred to as a draftsman or draughtsman.

Painting

Painting taken literally is the practice of applying pigment suspended in a carrier (or medium) and a binding agent (a glue) to a surface (support) such as paper, canvas or a wall. However, when used in an artistic sense it means the use of this activity in combination with drawing, composition and other aesthetic considerations in order to manifest the expressive and conceptual intention of the practitioner. Painting is also used to express spiritual motifs and ideas; sites of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery to The Sistine Chapel to the human body itself.

Colour is highly subjective, but has observable psychological effects, although these can differ from one culture to the next. Black is associated with mourning in the West, but elsewhere white may be. Some painters, theoreticians, writers and scientists, including Goethe, Kandinsky, Isaac Newton, have written their own colour theories. Moreover, the use of language is only a generalization for a colour equivalent. The word "red", for example, can cover a wide range of variations on the pure red of the spectrum. There is not a formalized register of different colours in the way that there is agreement on different notes in music, such as C or C# in music, although the Pantone system is widely used in the printing and design industry for this purpose.

Modern artists have extended the practice of painting considerably to include, for example, collage. This began with cubism and is not painting in strict sense. Some modern painters incorporate different materials such as sand, cement, straw or wood for their texture. Examples of this are the works of Jean Dubuffet or Anselm Kiefer. Modern and contemporary art has moved away from the historic value of craft in favour of concept; this has led some to say that painting, as a serious art form, is dead, although this has not deterred the majority of artists from continuing to practise it either as whole or part of their work.

Origin of the term

The word "humanities" is derived from the Renaissance Latin expression studia humanitatis, or "study of humanitas" (a classical Latin word meaning—in addition to "humanity"—"culture, refinement, education" and, specifically, an "education befitting a cultivated man"). In its usage in the early 15th century, the studia humanitatis was a course of studies that consisted of grammar, poetry, rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy, primarily derived from the study of Latin and Greek classics. The word humanitas also gave rise to the Renaissance Italian neologism umanisti, whence "humanist", "Renaissance humanism".[41]

History

In the West, the history of the humanities can be traced to ancient Greece, as the basis of a broad education for citizens.[42] During Roman times, the concept of the seven liberal arts evolved, involving grammar, rhetoric and logic (the trivium), along with arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music (the quadrivium).[43] These subjects formed the bulk of medieval education, with the emphasis being on the humanities as skills or "ways of doing".

A major shift occurred with the Renaissance humanism of the fifteenth century, when the humanities began to be regarded as subjects to study rather than practice, with a corresponding shift away from traditional fields into areas such as literature and history. In the 20th century, this view was in turn challenged by the postmodernist movement, which sought to redefine the humanities in more egalitarian terms suitable for a democratic society since the Greek and Roman societies in which the humanities originated were not at all democratic.[44] This was in keeping with the postmodernists' nuanced view of themselves as the culmination of history.

Today

Education and employment

For many decades, there has been a growing public perception that a humanities education inadequately prepares graduates for employment.[45] The common belief is that graduates from such programs face underemployment and incomes too low for a humanities education to be worth the investment.[46]

In fact, humanities graduates find employment in a wide variety of management and professional occupations. In Britain, for example, over 11,000 humanities majors found employment in the following occupations:

- Education (25.8%)

- Management (19.8%)

- Media/Literature/Arts (11.4%)

- Law (11.3%)

- Finance (10.4%)

- Civil service (5.8%)

- Not-for-profit (5.2%)

- Marketing (2.3%)

- Medicine (1.7%)

- Other (6.4%)[47]

Many humanities graduates finish university with no career goals in mind.[48][49] Consequently, many spend the first few years after graduation deciding what to do next, resulting in lower incomes at the start of their career; meanwhile, graduates from career-oriented programs experience more rapid entry into the labour market. However, usually within five years of graduation, humanities graduates find an occupation or career path that appeals to them.[50][51]

There is empirical evidence that graduates from humanities programs earn less than graduates from other university programs.[52][53][54] However, the empirical evidence also shows that humanities graduates still earn notably higher incomes than workers with no postsecondary education, and have job satisfaction levels comparable to their peers from other fields.[55] Humanities graduates also earn more as their careers progress; ten years after graduation, the income difference between humanities graduates and graduates from other university programs is no longer statistically significant.[48] Humanities graduates can earn even higher incomes if they obtain advanced or professional degrees.[56][57]

In the United States

The Humanities Indicators

The Humanities Indicators, unveiled in 2009 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, are the first comprehensive compilation of data about the humanities in the United States, providing scholars, policymakers and the public with detailed information on humanities education from primary to higher education, the humanities workforce, humanities funding and research, and public humanities activities.[58][59] Modeled after the National Science Board's Science and Engineering Indicators, the Humanities Indicators are a source of reliable benchmarks to guide analysis of the state of the humanities in the United States.

If "The STEM Crisis Is a Myth",[60] statements about a "crisis" in the humanities are also misleading and ignore data of the sort collected by the Humanities Indicators.[61][62]

The Humanities in American Life

The 1980 United States Rockefeller Commission on the Humanities described the humanities in its report, The Humanities in American Life:

Through the humanities we reflect on the fundamental question: What does it mean to be human? The humanities offer clues but never a complete answer. They reveal how people have tried to make moral, spiritual, and intellectual sense of a world where irrationality, despair, loneliness, and death are as conspicuous as birth, friendship, hope, and reason.

As a major

In 1950, a little over 1 percent of 22-year-olds in the United States had earned a humanities degrees (defined as a degree in English, language, history, philosophy); in 2010, this had doubled to about 2 and a half percent.[63] In part, this is because there was an overall rise in the number of Americans who have any kind of college degree. (In 1940, 4.6 percent had a four-year degree; in 2016, 33.4 percent had one.)[64] As a percentage of the type of degrees awarded, however, the humanities seem to be declining. Harvard University provides one example. In 1954, 36 percent of Harvard undergraduates majored in the humanities, but in 2012, only 20 percent took that course of study.[65] Professor Benjamin Schmidt of Northeastern University has documented that between 1990 and 2008, degrees in English, history, foreign languages, and philosophy have decreased from 8 percent to just under 5 percent of all U.S. college degrees.[66]

In liberal arts education

The Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences 2013 report The Heart of the Matter supports the notion of a broad "liberal arts education", which includes study in disciplines from the natural sciences to the arts as well as the humanities.[67][68]

Many colleges provide such an education; some require it. The University of Chicago and Columbia University were among the first schools to require an extensive core curriculum in philosophy, literature, and the arts for all students.[69] Other colleges with nationally recognized, mandatory programs in the liberal arts are Fordham University, St. John's College, Saint Anselm College and Providence College. Prominent proponents of liberal arts in the United States have included Mortimer J. Adler[70] and E. D. Hirsch, Jr..

In the digital age

Researchers in the humanities have developed numerous large- and small-scale digital corporation, such as digitized collections of historical texts, along with the digital tools and methods to analyze them. Their aim is both to uncover new knowledge about corpora and to visualize research data in new and revealing ways. Much of this activity occurs in a field called the digital humanities.

STEM

Politicians in the United States currently espouse a need for increased funding of the STEM fields, science, technology, engineering, mathematics.[71] Federal funding represents a much smaller fraction of funding for humanities than other fields such as STEM or medicine.[72] The result was a decline of quality in both college and pre-college education in the humanities field.[72]

Former four-term Louisiana Governor, Edwin Edwards (D), has recently acknowledged the importance of the humanities. In a video address[73] to the academic conference,[74] Revolutions in Eighteenth-Century Sociability, Edwards said

- Without the humanities to teach us how history has succeeded or failed in directing the fruits of technology and science to the betterment of our tribe of homo sapiens, without the humanities to teach us how to frame the discussion and to properly debate the uses-and the costs-of technology, without the humanities to teach us how to safely debate how to create a more just society with our fellow man and woman, technology and science would eventually default to the ownership of—and misuse by—the most influential, the most powerful, the most feared among us.[75]

In Europe

The value of the humanities debate

The contemporary debate in the field of critical university studies centers around the declining value of the humanities.[76][77] As in America, there is a perceived decline in interest within higher education policy in research that is qualitative and does not produce marketable products. This threat can be seen in a variety of forms across Europe, but much critical attention has been given to the field of research assessment in particular. For example, the UK [Research Excellence Framework] has been subject to criticism due to its assessment criteria from across the humanities, and indeed, the social sciences.[78] In particular, the notion of "impact" has generated significant debate.[79]

In Asia

In India, there are many institutions that offer undergraduate UG or bachelor's degree/diploma and postgraduate PG or master's degree/diploma as well as doctoral PhD and postdoctoral studies and research, in this academic discipline.

Philosophical history

Citizenship and self-reflection

Since the late 19th century, a central justification for the humanities has been that it aids and encourages self-reflection—a self-reflection that, in turn, helps develop personal consciousness or an active sense of civic duty.

Wilhelm Dilthey and Hans-Georg Gadamer centered the humanities' attempt to distinguish itself from the natural sciences in humankind's urge to understand its own experiences. This understanding, they claimed, ties like-minded people from similar cultural backgrounds together and provides a sense of cultural continuity with the philosophical past.[80]

Scholars in the late 20th and early 21st centuries extended that "narrative imagination"[81] to the ability to understand the records of lived experiences outside of one's own individual social and cultural context. Through that narrative imagination, it is claimed, humanities scholars and students develop a conscience more suited to the multicultural world we live in.[82] That conscience might take the form of a passive one that allows more effective self-reflection[83] or extend into active empathy that facilitates the dispensation of civic duties a responsible world citizen must engage in.[82] There is disagreement, however, on the level of influence humanities study can have on an individual and whether or not the understanding produced in humanistic enterprise can guarantee an "identifiable positive effect on people."[84]

Humanistic theories and practices

There are three major branches of knowledge: natural sciences, social sciences, and the humanities. Technology is the practical extension of the natural sciences, as politics is the extension of the social sciences. Similarly, the humanities have their own practical extension, sometimes called "transformative humanities" (transhumanities) or "culturonics" (Mikhail Epstein's term):

- Nature – natural sciences – technology – transformation of nature

- Society – social sciences – politics – transformation of society

- Culture – human sciences – culturonics – transformation of culture[85]

Technology, politics and culturonics are designed to transform what their respective disciplines study: nature, society, and culture. The field of transformative humanities includes various practicies and technologies, for example, language planning, the construction of new languages, like Esperanto, and invention of new artistic and literary genres and movements in the genre of manifesto, like Romanticism, Symbolism, or Surrealism. Humanistic invention in the sphere of culture, as a practice complementary to scholarship, is an important aspect of the humanities.

Truth and meaning

The divide between humanistic study and natural sciences informs arguments of meaning in humanities as well. What distinguishes the humanities from the natural sciences is not a certain subject matter, but rather the mode of approach to any question. Humanities focuses on understanding meaning, purpose, and goals and furthers the appreciation of singular historical and social phenomena—an interpretive method of finding "truth"—rather than explaining the causality of events or uncovering the truth of the natural world.[86] Apart from its societal application, narrative imagination is an important tool in the (re)production of understood meaning in history, culture and literature.

Imagination, as part of the tool kit of artists or scholars, helps create meaning that invokes a response from an audience. Since a humanities scholar is always within the nexus of lived experiences, no "absolute" knowledge is theoretically possible; knowledge is instead a ceaseless procedure of inventing and reinventing the context a text is read in. Poststructuralism has problematized an approach to the humanistic study based on questions of meaning, intentionality, and authorship. In the wake of the death of the author proclaimed by Roland Barthes, various theoretical currents such as deconstruction and discourse analysis seek to expose the ideologies and rhetoric operative in producing both the purportedly meaningful objects and the hermeneutic subjects of humanistic study. This exposure has opened up the interpretive structures of the humanities to criticism that humanities scholarship is "unscientific" and therefore unfit for inclusion in modern university curricula because of the very nature of its changing contextual meaning.

Pleasure, the pursuit of knowledge and scholarship

Some, like Stanley Fish, have claimed that the humanities can defend themselves best by refusing to make any claims of utility.[87] (Fish may well be thinking primarily of literary study, rather than history and philosophy.) Any attempt to justify the humanities in terms of outside benefits such as social usefulness (say increased productivity) or in terms of ennobling effects on the individual (such as greater wisdom or diminished prejudice) is ungrounded, according to Fish, and simply places impossible demands on the relevant academic departments. Furthermore, critical thinking, while arguably a result of humanistic training, can be acquired in other contexts.[88] And the humanities do not even provide any more the kind of social cachet (what sociologists sometimes call "cultural capital") that was helpful to succeed in Western society before the age of mass education following World War II.

Instead, scholars like Fish suggest that the humanities offer a unique kind of pleasure, a pleasure based on the common pursuit of knowledge (even if it is only disciplinary knowledge). Such pleasure contrasts with the increasing privatization of leisure and instant gratification characteristic of Western culture; it thus meets Jürgen Habermas' requirements for the disregard of social status and rational problematization of previously unquestioned areas necessary for an endeavor which takes place in the bourgeois public sphere. In this argument, then, only the academic pursuit of pleasure can provide a link between the private and the public realm in modern Western consumer society and strengthen that public sphere that, according to many theorists, is the foundation for modern democracy.

Others, like Mark Bauerlein, argue that professors in the humanities have increasingly abandoned proven methods of epistemology (I care only about the quality of your arguments, not your conclusions.) in favor of indoctrination (I care only about your conclusions, not the quality of your arguments.). The result is that professors and their students adhere rigidly to a limited set of viewpoints, and have little interest in, or understanding of, opposing viewpoints. Once they obtain this intellectual self-satisfaction, persistent lapses in learning, research, and evaluation are common.[89]

Romanticization and rejection

Implicit in many of these arguments supporting the humanities are the makings of arguments against public support of the humanities. Joseph Carroll asserts that we live in a changing world, a world where "cultural capital" is replaced with scientific literacy, and in which the romantic notion of a Renaissance humanities scholar is obsolete. Such arguments appeal to judgments and anxieties about the essential uselessness of the humanities, especially in an age when it is seemingly vitally important for scholars of literature, history and the arts to engage in "collaborative work with experimental scientists or even simply to make "intelligent use of the findings from empirical science."[90]

Despite many humanities based arguments against the humanities some within the exact sciences have called for their return. In 2017, Science popularizer Bill Nye retracted previous claims about the supposed 'uselessness' of philosophy. As Bill Nye states, “People allude to Socrates and Plato and Aristotle all the time, and I think many of us who make those references don’t have a solid grounding,” he said. “It’s good to know the history of philosophy.”[91] Scholars, such as biologist Scott F. Gilbert, make the claim that it is in fact the increasing predominance, leading to exclusivity, of scientific ways of thinking that need to be tempered by historical and social context. Gilbert worries that the commercialization that may be inherent in some ways of conceiving science (pursuit of funding, academic prestige etc.) need to be examined externally. Gilbert argues "First of all, there is a very successful alternative to science as a commercialized march to “progress.” This is the approach taken by the liberal arts college, a model that takes pride in seeing science in context and in integrating science with the humanities and social sciences."[92]

See also

- Discourse analysis

- Outline of the humanities (humanities topics)

- Great Books

- Great Books programs in Canada

- Liberal arts

- Social sciences

- Human science

- The Two Cultures

- List of academic disciplines

- Public humanities

- "Periodic Table of Human Sciences" in Tinbergen's four questions

- Environmental humanities

References

- Oxford English Dictionary 3rd Edition.

- "Humanity" 2.b, Oxford English Dictionary 3rd Ed. (2003)

- Bod, Rens (2013-11-14). A New History of the Humanities: The Search for Principles and Patterns from Antiquity to the Present. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665211.001.0001. ISBN 9780199665211.

- Stanford University, Stanford University. "What are the Humanities". Stanford Humanities Center. Stanford University. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "Humanist" Oxford English Dictionary. Oed.com

- Wallace and Gach (2008) p.28

- Wallerstein, I. (2003). "Anthropology, Sociology, and Other Dubious Disciplines" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 44 (4): 453–465. doi:10.1086/375868.

- Lowie, Robert (1924). Primitive Religion. Routledge and Sons.; Tylor, Edward (1920). Primitive Culture. New York: J. P. Putnam's Sons. Originally published 1871.

- Nanda, Serena and Richard Warms. Culture Counts. Wadsworth. 2008. Chapter One

- Rosaldo, Renato. Culture and Truth: The remaking of social analysis. Beacon Press. 1993; Inda, John Xavier and Renato Rosaldo. The Anthropology of Globalization. Wiley-Blackwell. 2007

- Sinclair, Anthony (2016). "The Intellectual Base of Archaeological Research 2004-2013: a visualisation and analysis of its disciplinary links, networks of authors and conceptual language". Internet Archaeology (42). doi:10.11141/ia.42.8.

- Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; McBride, Bunny; Walrath, Dana (2010), Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge (13th ed.), Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-0-495-81082-7

- "Social Science Majors, University of Saskatchewan". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- Boeckx, Cedric. "Language as a Natural Object; Linguistics as a Natural Science" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-23.

- Thagard, Paul, Cognitive Science, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Robertson, Geoffrey (2006). Crimes Against Humanity. Penguin. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-14-102463-9.

- Hart, H. L. A. (1961). The Concept of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-876122-8.

- Dworkin, Ronald (1986). Law's Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-51836-5.

- Raz, Joseph (1979). The Authority of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-956268-7.

- Austin, John (1831). The Providence of Jurisprudence Determined.

- Etymonline Dictionary

- Merriam-Webster's Dictionary

- Thomas Nagel (1987). What Does It All Mean? A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, pp. 4–5.

- Kant, Immanuel (1785). Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, the first line.

- See, e.g., Brian Leiter "'Analytic' philosophy today names a style of doing philosophy, not a philosophical program or a set of substantive views. Analytic philosophers, crudely speaking, aim for argumentative clarity and precision; draw freely on the tools of logic; and often identify, professionally and intellectually, more closely with the sciences and mathematics than with the humanities."

- Politica. New York: Oxford. 1941. pp. 1253a.

|first=missing|last=(help) - Berger, Peter (1969). The Sacred Canopy. New York: Doubleday and Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-0385073059.

- Stephenson, Barry (2015). Rituals. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0199943524.

- Bell, Catherine (2009). Ritual. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0199735105.

- Hood, Bruce (2010). The Science of Superstition. New York: HarperOne. pp. xii. ISBN 978-0061452659.

- Segal, Robert (2015). Myth. New York: Oxford. p. 3. ISBN 978-0198724704.

- Douglas, Mary (2002). Purity and Danger. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415289955.

- Eliade, Mircea (1959). The Sacred and the Profane. New York: Harvest.

- Coward, Harold (1988). Sacred Word and Sacred Text. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. ISBN 978-0883446041.

- Berger, Peter (1990). The Sacred Canopy. New York: Anchor. ISBN 978-0385073059.

- McGuire, Meredith (2002). Religion: The Social Context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 0-534-54126-7.

- Kelly, Joseph (1989). The Problem of Evil in the Western Tradition. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-5104-6.

- Becker, Ernest (2009), The denial of death, Macmillan, pp. ix, ISBN 0029023106

- Turney, Jon (2003-09-06). "Does time fly?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- "Internet Modern History Sourcebook: Darwin, Freud, Einstein, Dada". www.fordham.edu. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- "humanism." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 11 Apr. 2012.

- Bod, Rens; A New History of the Humanities, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014.

- Levi, Albert W.; The Humanities Today, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1970.

- Walling, Donovan R.; Under Construction: The Role of the Arts and Humanities in Postmodern Schooling Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Indiana, 1997. Humanities comes from human

- Hersh, Richard H. (1997-03-01). "Intention and Perceptions A National Survey of Public Attitudes Toward Liberal Arts Education". Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning. 29 (2): 16–23. doi:10.1080/00091389709603100. ISSN 0009-1383.

- Williams, Mary Elizabeth. "Hooray for "worthless" education!". Salon. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- Kreager, Philip. "Humanities graduates and the British economy: The hidden impact" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-06.

- Adamuti-Trache, Maria; et al. (2006). "The Labour Market Value of Liberal Arts and Applied Education Programs: Evidence from British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Higher Education. 36: 49–74.

- Thought Vlogger (2018-08-06), What can you do with a humanities degree?, retrieved 2018-08-07

- Koc, Edwin W (2010). "The Liberal Arts Graduate College Hiring Market". National Association of Colleges and Employers: 14–21.

- "Ten Years After College: Comparing the Employment Experiences of 1992–93 Bachelor's Degree Recipients With Academic and Career Oriented Majors" (PDF).

- "The Cumulative Earnings of Postsecondary Graduates Over 20 Years: Results by Field of Study".

- "Earnings of Humanities Majors with a Terminal Bachelor's Degree".

- "Career earnings by college major".

- The State of the Humanities 2018: Graduates in the Workforce & Beyond. Cambridge, Massachusetts: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2018. pp. 5–6, 12, 19.

- "Boost in Median Annual Earnings Associated with Obtaining an Advanced Degree, by Gender and Field of Undergraduate Degree".

- "Earnings of Humanities Majors with an Advanced Degree".

- "American Academy of Arts & Sciences". Amacad.org. 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- "Humanities Indicators". Humanities Indicators. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- Charette, Robert N. (2013-08-30). "The STEM Crisis Is a Myth – IEEE Spectrum". Spectrum.ieee.org. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- Humanities Scholars See Declining Prestige, Not a Lack of Interest

- Debating the State of the Humanities

- Schmidt, Ben. "A Crisis in the Humanities? (10 June 2013)". The Chronicle. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Wilson, Reid (4 March 2017). "Census: More Americans have college degrees than ever before". The Hill. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (18 June 2013). "Humanities Committee Sounds an Alarm". New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Smith, Noah (14 August 2018). "The Great Recession Never Ended for College Humanities". Bloomberg.

- Humanities, social sciences critical to our future

- Colbert Report: The humanities do pay

- Louis Menand, "The Problem of General Education," in The Marketplace of Ideas (W. W. Norton, 2010), especially pp. 32–43.

- Adler, Mortimer J.; "A Guidebook to Learning: For the Lifelong Pursuit of Wisdom"

- "Whitehouse.gov". Archived from the original on 2014-10-21. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- America Is Raising A Generation Of Kids Who Can't Think Or Write Clearly, Business Insider

- YouTube

- Scedhs2014.uqam.ca

- Academia.edu

- Stefan Collini, "What Are Universities For?" (Penguin 2012)

- Helen Small, "The Value of the Humanities"(Oxford University Press 2013)

- Ochsner, Michael; Hug, Sven; Galleron, Ioana (2017). "The future of research assessment in the humanities: Bottom-up assessment procedures". Palgrave Communications. 3. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.20.

- Bulaitis, Zoe (31 October 2017). "Measuring impact in the humanities: Learning from accountability and economics in a contemporary history of cultural value". Palgrave Communications. 3 (1). doi:10.1057/s41599-017-0002-7.

- Dilthey, Wilhelm. The Formation of the Historical World in the Human Sciences, 103.

- von Wright, Moira. "Narrative imagination and taking the perspective of others," Studies in Philosophy and Education 21, 4–5 (July, 2002), 407–416.

- Nussbaum, Martha. Cultivating Humanity.

- Harpham, Geoffrey (2005). "Beneath and Beyond the Crisis of the Humanities". New Literary History. 36: 21–36. doi:10.1353/nlh.2005.0022.

- Harpham, 31.

- Mikhail Epstein. The Transformative Humanities: A Manifesto. New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012, p.12

- Dilthey, Wilhelm. The Formation of the Historical World in the Human Sciences, 103.

- Fish, Stanley, The New York Times

- Alan Liu, Laws of Cool, 2004,

- Bauerlein, Mark (13 November 2014). "Theory and the Humanities, Once More". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Jay treats it [theory] as transformative progress, but it impressed us as hack philosophizing, amateur social science, superficial learning, or just plain gamesmanship.

- ""Theory," Anti-Theory, and Empirical Criticism," Biopoetics: Evolutionary Explorations in the Arts, Brett Cooke and Frederick Turner, eds., Lexington, Kentucky: ICUS Books, 1999, pp. 144–145. 152.

- quoted from Olivia Goldhill, https://qz.com/960303/bill-nye-on-philosophy-the-science-guy-says-he-has-changed-his-mind. Retrieved 2019-10-12.

- Gilbert, S. F. (n.d.). 'Health Fetishism among the Nacirema: A fugue on Jenny Reardon's The Postgenomic Condition: Ethics, Justice, and Knowledge after the Genome (Chicago University Press, 2017) and Isabelle Stengers' Another Science is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science (Polity Press, 2018). Retrieved from https://ojs.uniroma1.it/index.php/Organisms/article/view/14346/14050.'

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Humanities |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Humanities |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Humanities. |

- Society for the History of the Humanities

- Institute for Comparative Research in Human and Social Sciences (ICR) – Japan

- The American Academy of Arts and Sciences – US

- Humanities Indicators – US

- National Humanities Center – US

- The Humanities Association – UK

- National Humanities Alliance

- National Endowment for the Humanities – US

- Australian Academy of the Humanities

- National

- American Academy Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences

- "Games and Historical Narratives" by Jeremy Antley – Journal of Digital Humanities

- Film about the Value of the Humanities