Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith (/bəˈhɑːiː, bəˈhaɪ/; Persian: بهائی Bahāʼi) is a religion teaching the essential worth of all religions, and the unity of all people.[1] Established by Baháʼu'lláh in 1863, it initially grew in Persia and parts of the Middle East, where it has faced ongoing persecution since its inception.[2] It is estimated to have between 5 and 8 million adherents, known as Baháʼís, spread throughout most of the world's countries and territories.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

|

Central figures |

|

History |

|

Other topics |

The religion has three central figures: the Báb (1819–1850), considered a herald who taught that God would soon send a prophet in the same way of Jesus or Muhammad, and was executed by Iranian authorities in 1850; Baháʼu'lláh (1817-1892), who claimed to be that prophet in 1863 and faced exile and imprisonment for most of his life; and his son, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1844-1921), who was released from confinement in 1908 and made teaching trips to Europe and America. Following ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's death in 1921, leadership of the religion fell to his grandson Shoghi Effendi (1897–1957). Baháʼís around the world annually elect local, regional, and national Spiritual Assemblies that govern the affairs of the religion, and every five years the members of all National Spiritual Assemblies elect the Universal House of Justice, the nine-member supreme governing institution of the worldwide Baháʼí community, which sits in Haifa, Israel, near the Shrine of the Báb.

Baháʼí teachings are in some ways similar to other monotheistic faiths: God is considered single and all-powerful. However, Baháʼu'lláh taught that religion is orderly and progressively revealed by Manifestations of God, who are the founders of major world religions throughout history; Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad being the most recent before the Báb and Baháʼu'lláh. Baháʼís regard the major religions as fundamentally unified in purpose, though varied in social practices and interpretations. There is a similar emphasis on the unity of all people, openly rejecting notions of racism and nationalism. At the heart of Baháʼí teachings is the goal of a unified world order that ensures the prosperity of all nations, races, creeds, and classes.[4][5]

Letters written by Baháʼu'lláh to various individuals, including some heads of state, have been collected and assembled into a canon of Baháʼí scripture, including works by his son ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, and the Báb, who is regarded as Baháʼu'lláh's forerunner. Prominent among Baháʼí literature are the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, Kitáb-i-Íqán, Some Answered Questions, and The Dawn-Breakers.

Etymology

In English-language use, the word Baháʼí is used either as an adjective to refer to the Baháʼí Faith or as a term for a follower of Baháʼu'lláh.[6] It is derived from the Arabic Baháʼ (بهاء), meaning "glory" or "splendor".[note 1]

The older term "Bahaʼism" (or "Bahaism") is still used,[7][8][9][10][11] for example as a variant of "Bahai Faith" by the US Library of Congress,[12] though it is now less common[13] and the Baháʼí community prefers "Baháʼí Faith".[14]

Beliefs

The teachings of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, form the foundation for Baháʼí belief.[15] Three principles are central to these teachings: the unity of God, the unity of religion, and the unity of humanity.[16] Baha'is believe that God periodically reveals his will through divine messengers, whose purpose is to transform the character of humankind and to develop, within those who respond, moral and spiritual qualities. Religion is thus seen as orderly, unified, and progressive from age to age.[17]

God

The Baháʼí writings describe a single, personal, inaccessible, omniscient, omnipresent, imperishable, and almighty God who is the creator of all things in the universe.[18] The existence of God and the universe is thought to be eternal, without a beginning or end.[19] Though inaccessible directly, God is nevertheless seen as conscious of creation, with a will and purpose that is expressed through messengers termed Manifestations of God.[20][21]

Baháʼí teachings state that God is too great for humans to fully comprehend, or to create a complete and accurate image of by themselves. Therefore, human understanding of God is achieved through his revelations via his Manifestations.[22][23] In the Baháʼí religion, God is often referred to by titles and attributes (for example, the All-Powerful, or the All-Loving), and there is a substantial emphasis on monotheism. The Baháʼí teachings state that the attributes which are applied to God are used to translate Godliness into human terms and also to help individuals concentrate on their own attributes in worshipping God to develop their potentialities on their spiritual path.[22][23] According to the Baháʼí teachings the human purpose is to learn to know and love God through such methods as prayer, reflection, and being of service to others.[22]

Religion

Baháʼí notions of progressive religious revelation result in their accepting the validity of the well known religions of the world, whose founders and central figures are seen as Manifestations of God. Religious history is interpreted as a series of dispensations, where each manifestation brings a somewhat broader and more advanced revelation that is rendered as a text of scripture and passed on through history with greater or lesser reliability but at least true in substance,[24] suited for the time and place in which it was expressed.[19] Specific religious social teachings (for example, the direction of prayer, or dietary restrictions) may be revoked by a subsequent manifestation so that a more appropriate requirement for the time and place may be established. Conversely, certain general principles (for example, neighbourliness, or charity) are seen to be universal and consistent. In Baháʼí belief, this process of progressive revelation will not end; it is, however, believed to be cyclical. Baháʼís do not expect a new manifestation of God to appear within 1000 years of Baháʼu'lláh's revelation.[25]

Baháʼí beliefs are sometimes described as syncretic combinations of earlier religious beliefs.[26] Baháʼís, however, assert that their religion is a distinct tradition with its own scriptures, teachings, laws, and history.[19][27] While the religion was initially seen as a sect of Islam, most religious specialists now see it as an independent religion, with its religious background in Shiʻa Islam being seen as analogous to the Jewish context in which Christianity was established.[28] Muslim institutions and clergy, both Sunni and Shia, consider Baháʼís to be deserters or apostates from Islam, which has led to Baháʼís being persecuted.[29][30] Baháʼís describe their faith as an independent world religion, differing from the other traditions in its relative age and in the appropriateness of Baháʼu'lláh's teachings to the modern context.[31] Baháʼu'lláh is believed to have fulfilled the messianic expectations of these precursor faiths.[32]

Human beings

The Baháʼí writings state that human beings have a "rational soul", and that this provides the species with a unique capacity to recognize God's status and humanity's relationship with its creator. Every human is seen to have a duty to recognize God through his messengers, and to conform to their teachings.[33] Through recognition and obedience, service to humanity and regular prayer and spiritual practice, the Baháʼí writings state that the soul becomes closer to God, the spiritual ideal in Baháʼí belief. According to Baháʼí belief when a human dies the soul is permanently separated from the body and carries on in the next world where it is judged based on the person's actions in the physical world. Heaven and Hell are taught to be spiritual states of nearness or distance from God that describe relationships in this world and the next, and not physical places of reward and punishment achieved after death.[34]

The Baháʼí writings emphasize the essential equality of human beings, and the abolition of prejudice. Humanity is seen as essentially one, though highly varied; its diversity of race and culture are seen as worthy of appreciation and acceptance. Doctrines of racism, nationalism, caste, social class, and gender-based hierarchy are seen as artificial impediments to unity.[16] The Baháʼí teachings state that the unification of humanity is the paramount issue in the religious and political conditions of the present world.[19]

Summary

| Texts and scriptures of the Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

| From the Báb |

| From Baháʼu'lláh |

| From ʻAbdu'l-Bahá |

| From Shoghi Effendi |

Shoghi Effendi, the head of the religion from 1921 to 1957, wrote the following summary of what he considered to be the distinguishing principles of Baháʼu'lláh's teachings, which, he said, together with the laws and ordinances of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas constitute the bedrock of the Baháʼí Faith:

The independent search after truth, unfettered by superstition or tradition; the oneness of the entire human race, the pivotal principle and fundamental doctrine of the Faith; the basic unity of all religions; the condemnation of all forms of prejudice, whether religious, racial, class or national; the harmony which must exist between religion and science; the equality of men and women, the two wings on which the bird of human kind is able to soar; the introduction of compulsory education; the adoption of a universal auxiliary language; the abolition of the extremes of wealth and poverty; the institution of a world tribunal for the adjudication of disputes between nations; the exaltation of work, performed in the spirit of service, to the rank of worship; the glorification of justice as the ruling principle in human society, and of religion as a bulwark for the protection of all peoples and nations; and the establishment of a permanent and universal peace as the supreme goal of all mankind—these stand out as the essential elements [which Baháʼu'lláh proclaimed].[35]

Social principles

The following principles are frequently listed as a quick summary of the Baháʼí teachings. They are derived from transcripts of speeches given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá during his tour of Europe and North America in 1912.[36][37] The list is not authoritative and a variety of such lists circulate.[27][38]

- Unity of God

- Unity of religion

- Unity of humanity

- Equality between women and men

- Elimination of all forms of prejudice

- World peace and a new world order

- Harmony of religion and science

- Independent investigation of truth

- Universal compulsory education

- Universal auxiliary language[note 2]

- Obedience to government and non-involvement in partisan politics.[note 3]

- Elimination of extremes of wealth and poverty

- Prohibition of slavery.

With specific regard to the pursuit of world peace, Baháʼu'lláh prescribed a world-embracing collective security arrangement for the establishment of a temporary era of peace referred to in the Baha'i teachings as the Lesser Peace. For the establishment of a lasting peace (The Most Great Peace) and the purging of the "overwhelming Corruptions" it is necessary that all the people of the world universally unite under a universal Faith.[39]

Covenant

The Baháʼí teachings speak of a "Greater Covenant",[40] being universal and endless, and a "Lesser Covenant", being unique to each religious dispensation. The Lesser Covenant is viewed as an agreement between a Messenger of God and his followers and includes social practices and the continuation of authority in the religion. At this time Baháʼís view Baháʼu'lláh's revelation as a binding lesser covenant for his followers; in the Baháʼí writings being firm in the covenant is considered a virtue to work toward.[41] The Greater Covenant is viewed as a more enduring agreement between God and humanity, where a Manifestation of God is expected to come to humanity about every thousand years, at times of turmoil and uncertainty. With unity as an essential teaching of the religion, Baháʼís follow an administration they believe is divinely ordained, and therefore see attempts to create schisms and divisions as efforts that are contrary to the teachings of Baháʼu'lláh. Schisms have occurred over the succession of authority, but any Baháʼí divisions have had relatively little success and have failed to attract a sizeable following.[42] The followers of such divisions are regarded as Covenant-breakers and shunned, essentially excommunicated.[41][43]

Canonical texts

The canonical texts are the writings of the Báb, Baháʼu'lláh, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi and the Universal House of Justice, and the authenticated talks of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. The writings of the Báb and Baháʼu'lláh are considered as divine revelation, the writings and talks of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and the writings of Shoghi Effendi as authoritative interpretation, and those of the Universal House of Justice as authoritative legislation and elucidation. Some measure of divine guidance is assumed for all of these texts.[44] Some of Baháʼu'lláh's most important writings include the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, literally the Most Holy Book, which defines many laws and practices for individuals and society,[45] the Kitáb-i-Íqán, literally the Book of Certitude, which became the foundation of much of Baháʼí belief,[46] the Gems of Divine Mysteries, which includes further doctrinal foundations, and the Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys which are mystical treatises.[47]

Mystical writings

Although the Baháʼí teachings have a strong emphasis on social and ethical issues, a number of foundational texts have been described as mystical.[19] The Seven Valleys is considered Baháʼu'lláh's "greatest mystical composition." It was written to a follower of Sufism, in the style of ʻAttar, the Persian Muslim poet,[48] and sets forth the stages of the soul's journey towards God. It was first translated into English in 1906, becoming one of the earliest available books of Baháʼu'lláh to the West. The Hidden Words is another book written by Baháʼu'lláh during the same period, containing 153 short passages in which Baháʼu'lláh claims to have taken the basic essence of certain spiritual truths and written them in brief form.[49]

History

| 1817 | Baháʼu'lláh was born in Tehran, Iran

|

| 1819 | The Báb was born in Shiraz, Iran

|

| 1844 | The Báb declares his mission in Shiraz, Iran

|

| 1850 | The Báb is publicly executed in Tabriz, Iran

|

| 1852 | Thousands of Bábís are executed |

| Baháʼu'lláh is imprisoned and forced into exile

| |

| 1863 | Baháʼu'lláh first announces his claim to divine revelation |

| He is forced to leave Baghdad for Constantinople, then Adrianople

| |

| 1868 | Baháʼu'lláh is forced into harsher confinement in ʻAkká, in present-day Israel

|

| 1892 | Baháʼu'lláh dies near ʻAkká |

| His Will appointed ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as successor

| |

| 1908 | ʻAbdu'l-Bahá is released from prison

|

| 1921 | ʻAbdu'l-Bahá dies in Haifa |

| His Will appointed Shoghi Effendi as Guardian

| |

| 1957 | Shoghi Effendi dies in England

|

| 1963 | The Universal House of Justice is first elected |

The Baháʼí Faith formed from the Iranian religion of the Báb, a merchant who began preaching a new interpretation of Shia Islam in 1844. The Báb's claim to divine revelation was rejected by the generality of Islamic clergy in Iran, ending in his public execution by authorities in 1850. The Báb taught that God would soon send a new messenger, and Baháʼís consider Baháʼu'lláh to be that person.[50] Although they are distinct movements, the Báb is so interwoven into Baháʼí theology and history that Baháʼís celebrate his birth, death, and declaration as holy days, consider him one of their three central figures (along with Baháʼu'lláh and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá), and a historical account of the Bábí movement (The Dawn-Breakers) is considered one of three books that every Baháʼí should "master" and read "over and over again".[51]

The Baháʼí community was mostly confined to the Iranian and Ottoman empires until after the death of Baháʼu'lláh in 1892, at which time he had followers in 13 countries of Asia and Africa.[52] Under the leadership of his son, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the religion gained a footing in Europe and America, and was consolidated in Iran, where it still suffers intense persecution.[2] After the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in 1921, the leadership of the Baháʼí community entered a new phase, evolving from a single individual to an administrative order with both elected bodies and appointed individuals.[53]

The Báb

On the evening of 22 May 1844, Siyyid ʻAlí-Muhammad of Shiraz gained his first convert and took on the title of "the Báb" (الباب "the Gate"), referring to his later claim to the status of Mahdi of Shiʻa Islam.[2] His followers were therefore known as Bábís. As the Báb's teachings spread, which the Islamic clergy saw as blasphemous, his followers came under increased persecution and torture.[19] The conflicts escalated in several places to military sieges by the Shah's army. The Báb himself was imprisoned and eventually executed in 1850.[54]

Baháʼís see the Báb as the forerunner of the Baháʼí Faith, because the Báb's writings introduced the concept of "He whom God shall make manifest", a Messianic figure whose coming, according to Baháʼís, was announced in the scriptures of all of the world's great religions, and whom Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, claimed to be in 1863.[19] The Báb's tomb, located in Haifa, Israel, is an important place of pilgrimage for Baháʼís. The remains of the Báb were brought secretly from Iran to the Holy Land and eventually interred in the tomb built for them in a spot specifically designated by Baháʼu'lláh.[55] The main written works translated into English of the Báb's are collected in Selections from the Writings of the Báb out of the estimated 135 works.[56]

Baháʼu'lláh

Mírzá Husayn ʻAlí Núrí was one of the early followers of the Báb, and later took the title of Baháʼu'lláh. Bábís faced a period of persecution that peaked in 1852–53 after a few individuals made a failed attempt to assassinate the Shah. Although they acted alone, the government responded with collective punishment, killing many Bábís. Baháʼu'lláh was put in prison. He claimed that in 1853, while incarcerated in the dungeon of the Síyáh-Chál in Tehran, he received the first intimations that he was the one anticipated by the Báb when he received a visit from the Maid of Heaven.[16]

Shortly thereafter he was expelled from Tehran to Baghdad, in the Ottoman Empire;[16] then to Constantinople (now Istanbul); and then to Adrianople (now Edirne). In 1863, at the time of his banishment from Baghdad to Constantinople, Baháʼu'lláh declared his claim to a divine mission to his family and followers. Tensions then grew between him and Subh-i-Azal, the appointed leader of the Bábís who did not recognize Baháʼu'lláh's claim. Throughout the rest of his life Baháʼu'lláh gained the allegiance of most of the Bábís, who came to be known as Baháʼís. Beginning in 1866, he began declaring his mission as a Messenger of God in letters to the world's religious and secular rulers, including Pope Pius IX, Napoleon III, and Queen Victoria.

He produced over 18,000 works in his lifetime, in both Arabic and Persian, of which only 8% have been translated into English.[57]

Baháʼu'lláh was banished by Sultan Abdülaziz a final time in 1868 to the Ottoman penal colony of ʻAkká, in present-day Israel. Towards the end of his life, the strict and harsh confinement was gradually relaxed, and he was allowed to live in a home near ʻAkká, while still officially a prisoner of that city.[58] He died there in 1892. Baháʼís regard his resting place at Bahjí as the Qiblih to which they turn in prayer each day.[59]

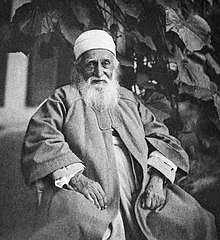

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

ʻAbbás Effendi was Baháʼu'lláh's eldest son, known by the title of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (Servant of Bahá). His father left a will that appointed ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as the leader of the Baháʼí community, and designated him as the "Centre of the Covenant", "Head of the Faith", and the sole authoritative interpreter of Baháʼu'lláh's writings.[55][60] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had shared his father's long exile and imprisonment, which continued until ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's own release as a result of the Young Turk Revolution in 1908. Following his release he led a life of travelling, speaking, teaching, and maintaining correspondence with communities of believers and individuals, expounding the principles of the Baháʼí Faith.[16]

There are over 27,000 extant documents by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, mostly letters, of which only a fraction have been translated into English.[56] Among the more well known are The Secret of Divine Civilization, the Tablet to Auguste-Henri Forel, and Some Answered Questions. Additionally notes taken of a number of his talks were published in various volumes like Paris Talks during his journeys to the West.

Shoghi Effendi

Baháʼu'lláh's Kitáb-i-Aqdas and The Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá are foundational documents of the Baháʼí administrative order. Baháʼu'lláh established the elected Universal House of Justice, and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá established the appointed hereditary Guardianship and clarified the relationship between the two institutions.[55][61] In his Will, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá appointed Shoghi Effendi, his eldest grandson, as the Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith. Shoghi Effendi served for 36 years as the head of the religion until his death.[62]

Shoghi Effendi throughout his lifetime translated Baháʼí texts; developed global plans for the expansion of the Baháʼí community; developed the Baháʼí World Centre; carried on a voluminous correspondence with communities and individuals around the world; and built the administrative structure of the religion, preparing the community for the election of the Universal House of Justice.[16] He unexpectedly died after a brief illness on 4 November 1957, in London, England, under conditions that did not allow for a successor to be appointed.[63][64][65]

In 1937, Shoghi Effendi launched a seven-year plan for the Baháʼís of North America, followed by another in 1946.[66] In 1953, he launched the first international plan, the Ten Year World Crusade. This plan included extremely ambitious goals for the expansion of Baháʼí communities and institutions, the translation of Baháʼí texts into several new languages, and the sending of Baháʼí pioneers into previously unreached nations.[67] He announced in letters during the Ten Year Crusade that it would be followed by other plans under the direction of the Universal House of Justice, which was elected in 1963 at the culmination of the Crusade. The House of Justice then launched a nine-year plan in 1964, and a series of subsequent multi-year plans of varying length and goals followed, guiding the direction of the international Baháʼí community.[68]

Universal House of Justice

Since 1963, the Universal House of Justice has been the elected head of the Baháʼí Faith. The general functions of this body are defined through the writings of Baháʼu'lláh and clarified in the writings of Abdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. These functions include teaching and education, implementing Baháʼí laws, addressing social issues, and caring for the weak and the poor.[70]

The House of Justice directs the work of the Baháʼí community through a series of multi-year international plans that began with a nine-year plan in 1964. In the current plan, the House of Justice encourages the Baháʼís around the world to focus on capacity building through children's classes, junior youth groups, devotional gatherings, and study circles.[71][72] Additional lines of action include social action and participation in the prevalent discourses of society.[73][74] The years from 2001 until 2021 represent four successive five-year plans, culminating in the centennial anniversary of the passing of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[75] Annually, on 21 April, the Universal House of Justice sends a 'Ridván' message to the worldwide Baháʼí community,[76] that updates Baháʼís on current developments and provides further guidance for the year to come.[note 4]

At local, regional, and national levels, Baháʼís elect members to nine-person Spiritual Assemblies, which run the affairs of the religion. There are also appointed individuals working at various levels, including locally and internationally, which perform the function of propagating the teachings and protecting the community. The latter do not serve as clergy, which the Baháʼí Faith does not have.[19][77] The Universal House of Justice remains the supreme governing body of the Baháʼí Faith, and its 9 members are elected every five years by the members of all National Spiritual Assemblies.[78] Any male Baháʼí, 21 years or older, is eligible to be elected to the Universal House of Justice; all other positions are open to male and female Baháʼís.[79]

Demographics

A Baháʼí-published document reported 4.74 million Baháʼís in 1986 growing at a rate of 4.4%.[80] Baháʼí sources since 1991 usually estimate the worldwide Baháʼí population to be above 5 million.[81] The World Christian Encyclopedia estimated 7.1 million Baháʼís in the world in 2000, representing 218 countries,[82] and 7.3 million in 2010[83] with the same source. They further state: "The Baha'i Faith is the only religion to have grown faster in every United Nations region over the past 100 years than the general population; Bahaʼi was thus the fastest-growing religion between 1910 and 2010, growing at least twice as fast as the population of almost every UN region."[84] This source's only systematic flaw was to consistently have a higher estimate of Christians than other cross-national data sets.[85]

The Baháʼí Faith is currently the largest religious minority in Iran,[86] Panama,[87] Belize,[88] and South Carolina;[89] the second largest international religion in Bolivia,[90] Zambia,[91] and Papua New Guinea;[92] and the third largest international religion in Chad[93][94] and Kenya.[95]

According to The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2004:

The majority of Baháʼís live in Asia (3.6 million), Africa (1.8 million), and Latin America (900,000). According to some estimates, the largest Baháʼí community in the world is in India, with 2.2 million Baháʼís, next is Iran, with 350,000, the US, with 150,000, and Brazil, with 60,000. Aside from these countries, numbers vary greatly. Currently, no country has a Baháʼí majority.[96]

The Baháʼí Faith is a medium-sized religion[97] and was listed in The Britannica Book of the Year (1992–present) as the second most widespread of the world's independent religions in terms of the number of countries represented. According to Britannica, the Baháʼí Faith (as of 2010) is established in 221 countries and territories and has an estimated seven million adherents worldwide.[3] Additionally, Baháʼís have self-organized in most of the nations of the world.

The Baháʼí religion was ranked by the Foreign Policy magazine as the world's second fastest growing religion by percentage (1.7%) in 2007.[98]

Social practices

Exhortations

The following are a few examples from Baháʼu'lláh's teachings on personal conduct that are required or encouraged of his followers:

- Baháʼís over the age of 15 should individually recite an obligatory prayer each day, using fixed words and form.

- In addition to the daily obligatory prayer, Baháʼís should offer daily devotional prayer and to meditate and study sacred scripture.

- Adult Baháʼís should observe a Nineteen-Day Fast each year during daylight hours in March, with certain exemptions.

- There are specific requirements for Baháʼí burial that include a specified prayer to be read at the interment. Embalming or cremating the body is strongly discouraged.

- Baháʼís should make a 19% voluntary payment on any wealth in excess of what is necessary to live comfortably, after the remittance of any outstanding debt. These Huqúqu'lláh payments are to be used for philanthropic purposes.

Prohibitions

The following are a few examples from Baháʼu'lláh's teachings on personal conduct that are prohibited or discouraged.

- Backbiting and gossip are prohibited and denounced.

- Drinking or selling alcohol is forbidden.

- Sexual intercourse is only permitted between a husband and wife, and thus premarital, extramarital, or homosexual intercourse are forbidden. (See also Homosexuality and the Baháʼí Faith)

- Abstaining from partisan politics is required.

- Begging as a profession is forbidden.

While some of the laws from the Kitáb-i-Aqdas are applicable at the present time, others are dependent upon the existence of a predominantly Baháʼí society, such as the punishments for arson or murder. The laws, when not in direct conflict with the civil laws of the country of residence, are binding on every Baháʼí,[99] and the observance of personal laws, such as prayer or fasting, is the sole responsibility of the individual.[100][101]

Marriage

The purpose of marriage in the Baháʼí faith is mainly to foster spiritual harmony, fellowship and unity between a man and a woman and to provide a stable and loving environment for the rearing of children.[102] The Baháʼí teachings on marriage call it a fortress for well-being and salvation and place marriage and the family as the foundation of the structure of human society.[103] Baháʼu'lláh highly praised marriage, discouraged divorce, and required chastity outside of marriage; Baháʼu'lláh taught that a husband and wife should strive to improve the spiritual life of each other.[104] Interracial marriage is also highly praised throughout Baháʼí scripture.[103]

Baháʼís intending to marry are asked to obtain a thorough understanding of the other's character before deciding to marry.[103] Although parents should not choose partners for their children, once two individuals decide to marry, they must receive the consent of all living biological parents, whether they are Baháʼí or not. The Baháʼí marriage ceremony is simple; the only compulsory part of the wedding is the reading of the wedding vows prescribed by Baháʼu'lláh which both the groom and the bride read, in the presence of two witnesses.[103] The vows are "We will all, verily, abide by the Will of God."[103]

Work

Baháʼu'lláh prohibited a mendicant and ascetic lifestyle.[105] Monasticism is forbidden, and Baháʼís are taught to practice spirituality while engaging in useful work.[19] The importance of self-exertion and service to humanity in one's spiritual life is emphasised further in Baháʼu'lláh's writings, where he states that work done in the spirit of service to humanity enjoys a rank equal to that of prayer and worship in the sight of God.[19]

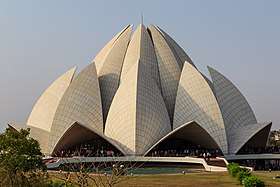

Places of worship

Most Baháʼí meetings occur in individuals' homes, local Baháʼí centers, or rented facilities. Worldwide, as of 2018, ten Baháʼí Houses of Worship, including eight Mother Temples and two local Houses of Worship have been built[106] and a further five are planned for construction. Two of these houses of worship are national while the other three are going to be local temples.[107] Baháʼí writings refer to an institution called a "Mas͟hriqu'l-Ad͟hkár" (Dawning-place of the Mention of God), which is to form the center of a complex of institutions including a hospital, university, and so on.[108] The first ever Mas͟hriqu'l-Ad͟hkár in ʻIshqábád, Turkmenistan, has been the most complete House of Worship.[109]

Calendar

The Baháʼí calendar is based upon the calendar established by the Báb. The year consists of 19 months, each having 19 days, with four or five intercalary days, to make a full solar year.[16] The Baháʼí New Year corresponds to the traditional Iranian New Year, called Naw Rúz, and occurs on the vernal equinox, near 21 March, at the end of the month of fasting. Baháʼí communities gather at the beginning of each month at a meeting called a Feast for worship, consultation and socializing.[19]

Each of the 19 months is given a name which is an attribute of God; some examples include Baháʼ (Splendour), ʻIlm (Knowledge), and Jamál (Beauty).[110] The Baháʼí week is familiar in that it consists of seven days, with each day of the week also named after an attribute of God. Baháʼís observe 11 Holy Days throughout the year, with work suspended on 9 of these. These days commemorate important anniversaries in the history of the religion.[111]

Symbols

The symbols of the religion are derived from the Arabic word Baháʼ (بهاء "splendor" or "glory"), with a numerical value of 9, which is why the most common symbol is the nine-pointed star.[112] The ringstone symbol and calligraphy of the Greatest Name are also often encountered. The former consists of two five-pointed stars interspersed with a stylized Baháʼ whose shape is meant to recall the three onenesses,[113] while the latter is a calligraphic rendering of the phrase Yá Baháʼu'l-Abhá (يا بهاء الأبهى "O Glory of the Most Glorious!").

The five-pointed star is the official symbol of the Baháʼí Faith,[114][115] known as the Haykal ("temple"). It was initiated and established by the Báb and various works were written in calligraphy shaped into a five-pointed star.[116]

Socio-economic development

Since its inception the Baháʼí Faith has had involvement in socio-economic development beginning by giving greater freedom to women,[118] promulgating the promotion of female education as a priority concern,[119] and that involvement was given practical expression by creating schools, agricultural co-ops, and clinics.[118]

The religion entered a new phase of activity when a message of the Universal House of Justice dated 20 October 1983 was released. Baháʼís were urged to seek out ways, compatible with the Baháʼí teachings, in which they could become involved in the social and economic development of the communities in which they lived. Worldwide in 1979 there were 129 officially recognized Baháʼí socio-economic development projects. By 1987, the number of officially recognized development projects had increased to 1482.[68]

Current initiatives of social action include activities in areas like health, sanitation, education, gender equality, arts and media, agriculture, and the environment.[120] Educational projects include schools, which range from village tutorial schools to large secondary schools, and some universities.[121] By 2017 there were an estimated 40,000 small scale projects, 1,400 sustained projects, and 135 Baháʼí inspired organizations.[120]

United Nations

Baháʼu'lláh wrote of the need for world government in this age of humanity's collective life. Because of this emphasis the international Baháʼí community has chosen to support efforts of improving international relations through organizations such as the League of Nations and the United Nations, with some reservations about the present structure and constitution of the UN.[121] The Baháʼí International Community is an agency under the direction of the Universal House of Justice in Haifa, and has consultative status with the following organizations:[122][123]

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)

- United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM)

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- World Health Organization (WHO)

The Baháʼí International Community has offices at the United Nations in New York and Geneva and representations to United Nations regional commissions and other offices in Addis Ababa, Bangkok, Nairobi, Rome, Santiago, and Vienna.[123] In recent years, an Office of the Environment and an Office for the Advancement of Women were established as part of its United Nations Office. The Baháʼí Faith has also undertaken joint development programs with various other United Nations agencies. In the 2000 Millennium Forum of the United Nations a Baháʼí was invited as the only non-governmental speaker during the summit.[124]

Persecution

Baháʼís continue to be persecuted in some majority-Islamic countries, whose leaders do not recognize the Baháʼí Faith as an independent religion, but rather as apostasy from Islam. The most severe persecutions have occurred in Iran, where more than 200 Baháʼís were executed between 1978 and 1998.[86] The rights of Baháʼís have been restricted to greater or lesser extents in numerous other countries, including Egypt, Afghanistan,[125] Indonesia,[126] Iraq,[127] Morocco,[128] Yemen,[129] and several countries in sub-Saharan Africa.[68]

Iran

The marginalization of the Iranian Baháʼís by current governments is rooted in historical efforts by Muslim clergy to persecute the religious minority.[130] When the Báb started attracting a large following, the clergy hoped to stop the movement from spreading by stating that its followers were enemies of God. These clerical directives led to mob attacks and public executions.[2] Starting in the twentieth century, in addition to repression aimed at individual Baháʼís, centrally directed campaigns that targeted the entire Baháʼí community and its institutions were initiated.[131] In one case in Yazd in 1903 more than 100 Baháʼís were killed.[132] Baháʼí schools, such as the Tarbiyat boys' and girls' schools in Tehran, were closed in the 1930s and 1940s, Baháʼí marriages were not recognized and Baháʼí texts were censored.[131][133]

During the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, to divert attention from economic difficulties in Iran and from a growing nationalist movement, a campaign of persecution against the Baháʼís was instituted.[note 5] An approved and coordinated anti-Baháʼí campaign (to incite public passion against the Baháʼís) started in 1955 and it included the spreading of anti-Baháʼí propaganda on national radio stations and in official newspapers.[131] During that campaign, initiated by Mulla Muhammad Taghi Falsafi, the Baha'i center in Tehran was demolished at the orders of Tehran military governor, General Timor Bakhtiar.[134] In the late 1970s the Shah's regime consistently lost legitimacy due to criticism that it was pro-Western. As the anti-Shah movement gained ground and support, revolutionary propaganda was spread which alleged that some of the Shah's advisors were Baháʼís.[135] Baháʼís were portrayed as economic threats, and as supporters of Israel and the West, and societal hostility against the Baháʼís increased.[131][136]

Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 Iranian Baháʼís have regularly had their homes ransacked or have been banned from attending university or from holding government jobs, and several hundred have received prison sentences for their religious beliefs, most recently for participating in study circles.[86] Baháʼí cemeteries have been desecrated and property has been seized and occasionally demolished, including the House of Mírzá Buzurg, Baháʼu'lláh's father.[2] The House of the Báb in Shiraz, one of three sites to which Baháʼís perform pilgrimage, has been destroyed twice.[2][137][138] In May 2018, the Iranian authorities expelled a young woman student from university of Isfahan because she was Baháʼí.[139] In March 2018, two more Baháʼí students were expelled from universities in the cities of Zanjan and Gilan because of their religion.

According to a US panel, attacks on Baháʼís in Iran increased under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's presidency.[140][141] The United Nations Commission on Human Rights revealed an October 2005 confidential letter from Command Headquarters of the Armed Forces of Iran ordering its members to identify Baháʼís and to monitor their activities. Due to these actions, the Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights stated on 20 March 2006, that she "also expresses concern that the information gained as a result of such monitoring will be used as a basis for the increased persecution of, and discrimination against, members of the Baháʼí faith, in violation of international standards. The Special Rapporteur is concerned that this latest development indicates that the situation with regard to religious minorities in Iran is, in fact, deteriorating."[142]

On 14 May 2008, members of an informal body known as the "Friends" that oversaw the needs of the Baháʼí community in Iran were arrested and taken to Evin prison.[140][143] The Friends court case has been postponed several times, but was finally underway on 12 January 2010.[144] Other observers were not allowed in the court. Even the defence lawyers, who for two years have had minimal access to the defendants, had difficulty entering the courtroom. The chairman of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom said that it seems that the government has already predetermined the outcome of the case and is violating international human rights law.[144] Further sessions were held on 7 February 2010,[145] 12 April 2010[146] and 12 June 2010.[147] On 11 August 2010 it became known that the court sentence was 20 years imprisonment for each of the seven prisoners[148] which was later reduced to ten years.[149] After the sentence, they were transferred to Gohardasht prison.[150] In March 2011 the sentences were reinstated to the original 20 years.[151] On 3 January 2010, Iranian authorities detained ten more members of the Baha'i minority, reportedly including Leva Khanjani, granddaughter of Jamaloddin Khanjani, one of seven Baha'i leaders jailed since 2008 and in February, they arrested his son, Niki Khanjani.[152]

The Iranian government claims that the Baháʼí Faith is not a religion, but is instead a political organization, and hence refuses to recognize it as a minority religion.[153] However, the government has never produced convincing evidence supporting its characterization of the Baháʼí community.[154] Also, the government's statements that Baháʼís who recanted their religion would have their rights restored, attest to the fact that Baháʼís are persecuted solely for their religious affiliation.[155] The Iranian government also accuses the Baháʼí Faith of being associated with Zionism.[156] These accusations against the Baháʼís have no basis in historical fact,[157][136][158] and the accusations are used by the Iranian government to use the Baháʼís as "scapegoats".[159] In fact it was the Iranian leader Naser al-Din Shah Qajar who banished Baháʼu'lláh from Iran to the Ottoman Empire and Baháʼu'lláh was later exiled by the Ottoman Sultan, at the behest of the Iranian Shah, to territories further away from Iran and finally to Acre in Syria, which only a century later was incorporated into the state of Israel.[160]

Egypt

During the 1920s Egypt's religious Tribunal recognized the Baha'i Faith as a new, independent religion, totally separate from Islam, due to the nature of the 'laws, principles and beliefs' of the Baha'is. At the same time the Tribunal condemned "in most unequivocal and emphatic language the followers of Baha'u'llah as the believers in heresy, offensive and injurious to Islam, and wholly incompatible with the accepted doctrines and practice of its orthodox adherents."[161]

Baháʼí institutions and community activities have been illegal under Egyptian law since 1960. All Baháʼí community properties, including Baháʼí centers, libraries, and cemeteries, have been confiscated by the government and fatwas have been issued charging Baháʼís with apostasy.[162]

The Egyptian identification card controversy began in the 1990s when the government modernized the electronic processing of identity documents, which introduced a de facto requirement that documents must list the person's religion as Muslim, Christian, or Jewish (the only three religions officially recognized by the government). Consequently, Baháʼís were unable to obtain government identification documents (such as national identification cards, birth certificates, death certificates, marriage or divorce certificates, or passports) necessary to exercise their rights in their country unless they lied about their religion, which conflicts with Baháʼí religious principle. Without documents, they could not be employed, educated, treated in hospitals, travel outside of the country, or vote, among other hardships.[163] Following a protracted legal process culminating in a court ruling favorable to the Baháʼís, the interior minister of Egypt released a decree on 14 April 2009, amending the law to allow Egyptians who are not Muslim, Christian, or Jewish to obtain identification documents that list a dash in place of one of the three recognized religions.[164] The first identification cards were issued to two Baháʼís under the new decree on 8 August 2009.[165]

See also

- Baháʼí Faith in fiction

- Baháʼí orthography

- Baha'i view on Muhammad

- Criticism of the Baháʼí Faith

- List of Baháʼís

- List of former Baháʼís

- Outline of the Baháʼí Faith

- Political objections to the Baháʼí Faith

- Terraces (Baháʼí), the Hanging Gardens of Haifa

Notes

- Baháʼís prefer the orthographies Baháʼí, Baháʼís, the Báb, Baháʼu'lláh, and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, using a particular transcription of the Arabic and Persian in publications. "Bahai", "Bahais", "Bahaʼi", "the Bab", "Bahaullah" and "Bahaʼullah" are often used when diacritics are unavailable.

- For an annotated compilation of excerpts from the Baháʼí writings regarding the principle of International or Universal Auxiliary Language, see The Greatest Instrument for Promoting Harmony and Civilization: Excerpts from the Baháʼí Writings and Related Sources on the Question of an International Auxiliary Language. Oxford: George Ronald. 2015. ISBN 978-085398-591-4

- Obedience to government is not applicable when submission to law amounts to a denial of Faith. See for example: Political Non-involvement and Obedience to Government – A compilation of some of the Messages of the Guardian and the Universal House of Justice (compiled by Dr. Peter J. Khan)

- All Ridván messages can be found at Bahai.org and Bahaiprayers.net/Ridvan (multi-lingual).

- In line with this is the thinking that the government encouraged the campaign to distract attention from more serious problems, including acute economic difficulties. Beyond this lay the difficulty which the regime faced in harnessing the nationalist movement that had supported Musaddiq.(Akhavi 1980, pp. 76–78)

Citations

- Dictionary 2017.

- Affolter 2005, pp. 75–114.

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2010.

- Hatcher & Martin 1998

- Moojan Momen (2011). "Bahaʼi". In Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Sage Publications. doi:10.4135/9781412997898.n61. ISBN 978-0-7619-2729-7.

- Stockman 2006.

- "Baha'i". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Denis McEoin (1994) Rituals in Babism and Bahaʼism. British Academic Press.

- Hvithamar, Warburg & Warmind, eds. (2005) Bahaʼi and Globalisation. Aarhus University Press.

- Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, (2008) "Anti-Bahaiʼism and Islamism in Iran". In Brookshaw & Fazel, eds. Bahaʼis of Iran: Routledge.

- Leyla Melikova (2013) "How Bahaʼism Travelled from the East to the West (Ideological Evolution of the Neo-Universalist Religious Doctrine). The Caucasus and Globalization, vol. 7, no. 3–4, pp. 115–130.

- "Bahai Faith". Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "We have used Bahaʼi Faith most frequently (rather than Bahaʼism) as this is the more commonly used name for the religion". 'Note on transliteration, dates and names', in Brookshaw & Fazel, eds. Bahaʼis of Iran: Socio-historical studies. Routledge, 2008.

- Hatcher & Martin 1998, p. xiii.

- Esslemont, J. E. (1980). Baháʼu'lláh and the New Era (Fifth ed.). US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 5.

- Hutter 2005, pp. 737–740.

- Smith 2008, pp. 108–109.

- Smith 2008, p. 106.

- Daume & Watson 1992.

- Smith 2008, pp. 106–107.

- Smith 2008, pp. 111–112.

- Hatcher 2005, pp. 1–38.

- Cole 1982, pp. 1–38.

- Robert H. Stockman (2012). The Baha'i Faith: A Guide For The Perplexed. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-1-4411-0447-2.

- McMullen 2000, p. 7.

- Stockman 1997.

- Bausani 2012.

- Van der Vyer 1996, p. 449.

- Boyle & Sheen 1997, pp. 119–120.

- Afshari 2001, pp. 119–120.

- Lundberg 2005.

- Buck (2004), pp. 143–178.

- McMullen 2000, pp. 57–58.

- Masumian 1995.

- Effendi 1944, pp. 281–282.

- Smith 2008, pp. 52–53.

- Principles of the Baháʼí Faith & 26 March 2006.

- Cole 1989, pp. 438–446: "Bahaism: The Faith"

- Smith 2000, pp. 266–267.

- Taherzadeh 1972.

- Momen 1995: "Lower covenant"

- MacEoin 1989, p. 448.

- Smith 2008, p. 173.

- Smith 2000, pp. 100–101: "Canonical texts"

- Hatcher & Martin 1998, p. 46.

- Hatcher & Martin 1998, p. 137.

- Smith 2008, p. 20.

- Smith 2000, p. 311: "Seven Valleys"

- Smith 2000, p. 181: "Hidden Words"

- A.V. 2017.

- From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer dated 9 June 1932

- Taherzadeh 1987, p. 125.

- Smith 2008, p. 56.

- Winter 1997.

- Balyuzi 2001.

- Universal House of Justice & September 2002, pp. 349–350.

- Stockman, R. H. (2012). The Baha'i Faith: A Guide For The Perplexed. A&C Black. pp. 2

- Cole 1989, pp. 422–429: "BAHĀʾ-ALLĀH"

- Smith 2008, pp. 20–21, 28.

- Smith 2008, p. 47.

- Smith 2008, pp. 55–57.

- Smith 2008, p. 55.

- Taherzadeh 2000, pp. 347–363.

- Smith 2008, pp. 58–69.

- "Shoghi Effendi, 61, Baha'i Faith Leader". New York Times. 6 November 1957.

- Danesh, Danesh & Danesh 1991.

- Hassal 1996, pp. 1–21.

- Smith & Momen 1989, pp. 63–91.

- Ryan 1987, p. 6.

- Momen, Moojan. "Bayt-al-'Adl (House of Justice)". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Gervais 2008.

- Universal House of Justice & 17 January 2003.

- Vahedi & 2 March 2011.

- Universal House of Justice & 21 April 2010.

- Universal House Of Justice 2006.

- Smith 2000, p. 297: "Ridván"

- Smith 2008, p. 160.

- Stockman 1995.

- Smith 2008, p. 205.

- Rabbani & July 1987, pp. 2–7.

- Baháʼí World News Service 2010.

- Barrett 2001, p. 4.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010.

- Johnson & Grim 2013, pp. 59–62.

- Hsu et al. 2008, pp. 691–692.

- International Federation of Human Rights & August 2003.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profile: Panama.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profile: Belize.

- "The second-largest religion in each state". Washington Post. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profile: Bolivia.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profile: Zambia.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profile: Papua New Guinea.

- Religious Intelligence: Country Profile: Chad

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profile: Chad.

- Association of Religion Data Archives 2010, National Profiles: Kenya.

- Park 2004.

- Lewis 2008, p. 118: "Baha'i ... is a medium-sized religion of seven million adherents."

- Foreign Policy Magazine & 1 May 2007.

- Smith 2008, p. 158.

- Smith 2000, pp. 223–225: "Law"

- Walbridge 1996.

- Smith 2008, pp. 164–165.

- Smith 2008, p. 164.

- Baha'is of Warwick & 12 October 2003.

- Smith 2008, pp. 154–155.

- "Baha'i Temples A Brief Introduction". Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- "Houses of Worship". Baha'i World News Services. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Smith 2008, p. 194.

- Smith 2000, p. 236: "Mashriqu'l-Adkhar"

- Smith 2008, pp. 188–190.

- Smith 2008, p. 188.

- Smith 2000, pp. 167–168: "Greatest Name"

- Faizi 1968.

- Effendi 1973, pp. 51–52.

- Bahai-library.com & Nine-Pointed Star.

- Beyer 2017.

- Baháʼí International Community 2005.

- Momen 1994: Section 9: Social and economic development

- Kingdon 1997.

- Baháʼí Office of Social and Economic Development 2018.

- Momen 2007.

- McMullen 2000, p. 39.

- Baháʼí International Community & 6 June 2000.

- Baháʼí World News Service & 8 September 2000.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2013, Afghanistan.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2013, Indonesia.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2013, Iraq.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2013, Morocco.

- Baháʼí World News Service. Ominous wave of Yemen arrests raises alarm (21 April 2017).

- Archives of Bahá'í Persecution in Iran: Historical Overview

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 2007.

- Nash 1982.

- Sanasarian 2000, pp. 52–53.

- "Iran Razing Dome of Bahai Temple". New York Times.

- Abrahamian 1982, p. 432.

- Simpson & Shubart 1995, p. 223.

- Netherlands Institute of Human Rights & 8 March 2006.

- Baháʼí World News Service 2005.

- "Woman Expelled From Iranian University Just Before Obtaining Degree Because She's Baha'i". Center for Human Rights in Iran. 29 July 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- CNN & 16 May 2008.

- Sullivan & 8 December 2009.

- Jahangir 2006.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center & 15 May 2008.

- CNN & 12 January 2010.

- Washington TV 2010.

- Djavadi & 8 April 2010.

- Radio Free Europe & 3 June 2010.

- Siegal 2010.

- CNN & 16 September 2010.

- AFP & 16 February 2011.

- AFP & 31 March 2011.

- The Jerusalem Post & 14 February 2010.

- Kravetz 1982, p. 237.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 2008, p. 5.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 2007, p. 9.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 2007, Statement of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Buenos Aires, 26 September 1979.

- Cooper 1993, p. 20.

- Tavakoli-Targhi 2008, p. 200.

- Freedman & 26 June 2009.

- Momen 2004, pp. 27–29.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1974). Baha'i Administration, Selected Messages 1922–1932. Wilmette, IL: Baha'i Publishing Trust. p. 121.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2013, Egypt.

- Bigelow & 16 November 2005.

- Baháʼí World News Service & 17 April 2009.

- Baháʼí World News Service & 14 August 2009.

References

- Beyer, Catherine (8 March 2017). "Baha'i Faith Symbol Gallery". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 4 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton Book Company Publishers. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adherents (18 October 2001). "Baha'i Houses of Worship". Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Affolter, Friedrich W. (January 2005). "The Specter of Ideological Genocide: The Baháʼís of Iran" (PDF). War Crimes, Genocide, & Crimes Against Humanity. 1 (1): 75–114. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Afshari, Reza (2001). Human rights in Iran: the abuse of cultural relativism. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-8122-3605-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Akhavi, Shahrough (1980). Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran: Clergy-State Relations in the Pahlavi Period. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. pp. 76–78. ISBN 0-87395-408-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Association of Religion Data Archives (2010). "Most Baha'i Nations (2010)". Retrieved 20 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baháʼí International Community (2005). "History of Baháʼí Educational Efforts in Iran". Closed Doors: Iran's Campaign to Deny Higher Education to Baháʼís.

- "Nine-Pointed Star, The:History and Symbolism by Universal House of Justice 1999-01-24". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Baha'is of Warwick (12 October 2003). "Baha'i Marriage". Archived from the original on 28 May 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- Baháʼí World News Service (8 September 2000). "Baháʼí United Nations Representative Addresses World Leaders at the Millennium Summit". Baháʼí International Community. Archived from the original on 22 April 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- Baháʼí World News Service (14 April 2005). "Dismay at lack of human rights resolution on Iran as persecution worsens". Newswire. Baháʼí International Community. Retrieved 25 September 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balyuzi, Hasan (2001). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Baháʼu'lláh (Paperback ed.). Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-043-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bausani, A. (2012). "Bahāʾīs". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online (Second (online) ed.). Brill. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- Barrett, David A. (2001). "Global statistics for all religions: 2001 AD". World Christian Encyclopedia. p. 4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bigelow, Kit (16 November 2005). Kit Bigelow, Director of External Affairs, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States (Speech). Congressional Human Rights Caucus, House of Representatives. Archived from the original on 27 December 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- Boyle, Kevin; Sheen, Juliet (1997). Freedom of religion and belief: a world report. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 0-415-15978-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buck, Christopher (2004). "The eschatology of Globalization: The multiple-messiahship of Bahā'u'llāh revisited". In Sharon, Moshe (ed.). Studies in Modern Religions, Religious Movements and the Bābī-Bahā'ī Faiths. Boston: Brill. pp. 143–178. ISBN 90-04-13904-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Centre for Faith and the Media. A Journalist's Guide to the Baha'i Faith (PDF). Calgary, Alberta. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012.

- Cole, Juan (1982). The Concept of Manifestation in the Baháʼí Writings. Baháʼí Studies. monograph 9. pp. 1–38.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cole, Juan (1989). "Bahai Faith". Encyclopædia Iranica. III. New York. ISSN 2330-4804.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper, Roger (1993). Death Plus 10 years. HarperCollins. p. 20. ISBN 0-00-255045-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daume, Daphne; Watson, Louise, eds. (1992). "The Baháʼí Faith". Britannica Book of the Year. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica. ISBN 0-85229-486-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Danesh, Helen; Danesh, John; Danesh, Amelia (1991). "The Life of Shoghi Effendi". In Bergsmo, M. (ed.). Studying the Writings of Shoghi Effendi. George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-336-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1979). ISBN 0-87743-020-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Effendi, Shoghi (1973). "Directives from the Guardian". 141: NINE (Number). Baháʼí Reference Library. Reference.bahai.org. pp. 51–52. Retrieved 23 February 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Worldwide Adherents of All Religions by Six Continental Areas, Mid-2010". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Faizi, Abu'l-Qasim (1968). Explanation of the Symbol of the Greatest Name. New Delhi, India: Baháʼí Publishing Trust.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foreign Policy Magazine (1 May 2007). "The List: The World's Fastest-Growing Religions". Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- Gervais, Marie (2008). "Baha'i Faith and Peace Education" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Peace Education. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. Retrieved 3 May 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hassal, Graham (1996). "Baha'i History in the Formative Age" (PDF). Journal of Bahá'í Studies. 6 (4): 1–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hatcher, John S. (2005). Unveiling the Hurí of Love. Journal of Bahá'í Studies. 15. pp. 1–38.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hatcher, W.S.; Martin, J.D. (1998). The Baháʼí Faith: The Emerging Global Religion. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-065441-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "bahai". Dictionary.com Unabridged (4th ed.). Random House, Inc. 2017.

- Hutter, Manfred (2005). "Bahā'īs". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. 2 (2nd ed.). Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference US. pp. 737–740. ISBN 0-02-865733-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hsu, Becky; Reynolds, Amy; Hackett, Conrad; Gibbon, James (2008). "Estimating the Religious Composition of All Nations: An Empirical Assessment of the World Christian Database" (PDF). Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 47 (4): 691–692. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00435.x. Retrieved 27 January 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- International Federation of Human Rights (August 2003). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). Paris: FIDH. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (2013). "International Religious Freedom Report for 2013". United States Department of State. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2007). "A Faith Denied: The Persecution of the Baha'is of Iran" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (September 2007). Community Under Siege: The Ordeal of the Baháʼís of Shiraz (PDF). New Haven, CN. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2010.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2008). Crimes Against Humanity: The Islamic Republic's Attacks on the Baháʼís (PDF). New Haven, CN. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (26 March 2013). "Global Religious Populations, 1910–2010". The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 59–62. doi:10.1002/9781118555767.ch1. ISBN 9781118555767.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kingdon, Geeta Gandhi (1997). "Education of women and socio-economic development". Baha'i Studies Review. 7 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kravetz, Marc (1982). Irano nox (in French). Paris: Grasset. p. 237. ISBN 2-246-24851-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, James R (2008). Scientology. Oxford University Press. p. 118.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lundberg, Zaid (2005). "The Concept of Progressive Revelation". Baha'i Apocalypticism: The Concept of Progressive Revelation (Master of Arts thesis). Department of History of Religion at the Faculty of Theology, Lund University, Sweden. Retrieved 1 May 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacEoin, Denis (1989). "Bahaism: Bahai and Babi Schisms". Encyclopædia Iranica. III. New York. p. 448. ISSN 2330-4804.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McMullen, Michael D. (2000). The Baha'i: The Religious Construction of a Global Identity. Atlanta, GA: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2836-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Masumian, Farnaz (1995). Life After Death: A study of the afterlife in world religions. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-074-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meyjes (also: Posthumus Meyjes), Gregory Paul, ed. (2015). The Greatest Instrument for Promoting Harmony and Civilization: Excerpts from the Baháʼí Writings and Related Sources on the Question of an International Auxiliary Language. Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 978-085398-591-4.

- Momen, Moojan (1994). "Iran: History of the Baháʼí Faith". draft "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 16 October 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Momen, Moojan (1995). "The Covenant and Covenant-breaker". Retrieved 14 June 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Momen, Moojan (2004). "Conspiracies and Forgeries: the attack upon the Baha'i community in Iran". Persian Heritage. 9 (35): 27–29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Momen, Moojan (2007). "The Baháʼí Faith". In Partridge, Christopher H. (ed.). New Lion Handbook: The World's Religions (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Lion Hudson Plc. ISBN 978-0-7459-5266-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nash, Geoffrey (1982). Iran's secret pogrom: The conspiracy to wipe out the Bahaʼis. Sudbury, Suffolk: Neville Spearman Limited. ISBN 0-85435-005-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Netherlands Institute of Human Rights (8 March 2006). "Iran, Islamic Republic of". Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2006.

- Baháʼí Office of Social and Economic Development (2018). "For the Betterment of the World: The Worldwide Baháʼí Community's Approach to Social and Economic Development" (PDF). Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Park, Ken, ed. (2004). World Almanac and Book of Facts. New York: World Almanac Books. ISBN 0-88687-910-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Principles of the Baháʼí Faith". The Baháʼí Faith. 26 March 2006. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- "Country Profile: Chad". Religious Intelligence. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-521-77073-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, John; Shubart, Tira (1995). Lifting the Veil. London: Hodder & Stoughton General Division. p. 223. ISBN 0-340-62814-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Peter; Momen, Moojan (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19 (1): 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stockman, Robert (1992). "Jesus Christ in the Baha'i Writings". Baha'i Studies Review. London: Association for Baha'i Studies English-Speaking Europe. 2 (1).

- Stockman, Robert (1995). "Baháʼí Faith: A portrait". In Beversluis, Joel (ed.). A Source Book for Earth's Community of Religions. Grand Rapids, MI: CoNexus Press. ISBN 978-1-57731-121-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stockman, Robert (1997). "The Baha'i Faith and Syncretism". A Resource Guide for the Scholarly Study of the Baháʼí Faith.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stockman, Robert (2006). "Baha'i Faith". In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices. OCLC 61748247.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taherzadeh, Adib (1972). The Covenant of Baháʼu'lláh. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-344-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taherzadeh, Adib (1987). The Revelation of Baháʼu'lláh, Volume 4: Mazra'ih & Bahji 1877–92. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. p. 125. ISBN 0-85398-270-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taherzadeh, Adib (2000). The Child of the Covenant. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 347–363. ISBN 0-85398-439-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tavakoli-Targhi, Mohamad (2008). "Anti-Baha'ism and Islamism in Iran". In Brookshaw, Dominic P.; Fazel, Seena B. (eds.). The Baha'is of Iran: Socio-historical studies. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-00280-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jahangir, Asma (20 March 2006). "Special Rapporteur on Freedom of religion or belief concerned about treatment of followers of Baháʼí Faith in Iran". United Nations. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Universal House of Justice (September 2002). "Numbers and Classifications of Sacred Writings & Texts". Lights of Irfan. Wilmette, IL: Irfan Colloquia. 10: 349–350. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- Universal House of Justice (17 January 2003). "Letter dated 17 January 2003". bahai-library.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- Universal House Of Justice (2006). Five Year Plan 2006–2011. West Palm Beach, FL: Palabra Publications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Universal House of Justice (21 April 2010). "Ridván message 2010". Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Vahedi, Farida (2 March 2011). "A Discussion with Farida Vahedi, Executive Director of the Department of External Affairs, National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of India" (Interview). Interviewed by Michael Bodakowski. Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs at Georgetown University. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Van der Vyer, J.D. (1996). Religious human rights in global perspective: religious perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 449. ISBN 90-411-0176-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walbridge, John (1996). "Prayer and Worship". Sacred Acts, Sacred Space, Sacred Time. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. Retrieved 11 July 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winter, Jonah (17 September 1997). "Dying for God: Martyrdom in the Shii and Babi Religions". Master of Arts Thesis, University of Toronto.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

News reports

- A.V. (20 April 2017). "The Economist explains: The Bahai faith". The Economist. Retrieved 23 April 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- AFP (16 February 2011). "Families fear for Bahais jailed in Iran".

- AFP (31 March 2011). "US 'troubled' by Bahai reports from Iran".

- Baháʼí International Community (6 June 2000). "History of Active Cooperation with the United Nations" (Press release). Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Baháʼí World News Service (14 August 2009). "First identification cards issued to Egyptian Baháʼís using a "dash" instead of religion". Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- Baháʼí World News Service (17 April 2009). "Egypt officially changes rules for ID cards". Baháʼí International Community. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- Baháʼí World News Service (2010). "Statistics". Baháʼí International Community. Retrieved 5 March 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baháʼí World News Service (22 April 2012). "Plans to build new Houses of Worship announced". Baháʼí International Community. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- CNN (16 May 2008). "Iran's arrest of Baha'is condemned". Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- CNN (12 January 2010). "Trial underway for Baha'i leaders in Iran". Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- CNN (16 September 2010). "Sentences for Iran's Baha'i leaders reportedly reduced". Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Djavadi, Abbas (8 April 2010). "A Trial In Tehran: Their Only 'Crime' – Their Faith". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Freedman, Samuel G. (26 June 2009). "For Bahais, a Crackdown Is Old News". The New York Times.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (15 May 2008). "IHRDC Condemns the Arrest of Leading Baháʼís" (Press release). Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Rabbani, Ahang; Department of Statistics at the Baháʼí World Centre in Haifa, Israel (July 1987). "Achievements of the Seven Year Plan" (PDF). Baháʼí News. Baháʼí World Center, Haifa: Baháʼí International Community. pp. 2–7. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Ryan, Nancy (12 June 1987). "Bahais celebrate anniversary; Faith's House of Worship in Wilmette 75 years old". Chicago Tribune.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Siegal, Daniel (11 August 2010). "Court sentences leaders of Bahai faith to 20 years in prison". Los Angeles Times.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Iran detains 5 more Baha'i". The Jerusalem Post. 14 February 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Iran Baha'i Leaders Scheduled In Court On Election Anniversary". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 3 June 2010.

- Sullivan, Amy (8 December 2009). "Banning the Baha'i". Time. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Washington TV (20 January 2010). "Date set for second court session for seven Baha'is in Iran". Retrieved 21 January 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Adamson, Hugh C. (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford, UK: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810864673.

- Esslemont, John (1923). Baháʼu'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, IL: Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1980). ISBN 0-87743-160-4.

- Foltz, Richard (2013). Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present. London: Oneworld publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-308-0.

- Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8.

- Meyjes (also: Posthumus Meyjes), Gregory Paul (2006). "Language and World Order in Baháʼí Perspective: a New Paradigm Revealed". In Omoniyi, T.; Fishman, J. A. (eds.). Explorations in the Sociology of Language And Religion. Volume 20 of Discourse Approaches to Politics, Society, and Culture. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 26–41. ISBN 9789027227102.

- Momen, Moojan (1990). Hinduism and the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-299-6.

- Momen, Moojan (1994). Buddhism and the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-384-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Momen, Moojan (2000). Islam and the Baháʼí Faith, An Introduction to the Baháʼí Faith for Muslims. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-446-8.

- Schaefer, U.; Towfigh, N.; Gollmer, U. (2000). Making the Crooked Straight: A Contribution to Baháʼí Apologetics. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-443-3.

- Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stockman, Robert H. (2006). "The Baha'is of the United States". In Gallagher, Eugene V.; Ashcraft, W. Michael (eds.). Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America: Asian Traditions. 4. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-275-98712-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Townshend, George (1966). Christ and Baháʼu'lláh. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-005-5.