Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport

Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (IATA: ATL, ICAO: KATL, FAA LID: ATL), also known as Atlanta Hartsfield–Jackson International Airport, Atlanta Airport, Hartsfield, or Hartsfield–Jackson, is the primary international airport serving Atlanta, Georgia. The airport is located seven miles (11 km) south of the Downtown Atlanta district. It is named after former Atlanta mayors William B. Hartsfield and Maynard Jackson.[2] ATL covers 4,700 acres (1,902 ha) of land and has five parallel runways.[3][2]

Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City of Atlanta | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Atlanta Department of Aviation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Unincorporated areas of Fulton and Clayton counties; also Atlanta, College Park, and Hapeville, Georgia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 1,026 ft / 313 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°38′12″N 084°25′41″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www.atl.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

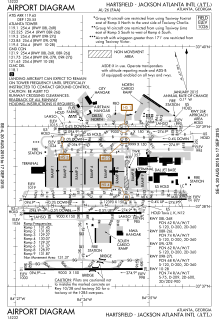

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ATL Location of airport in Metro Atlanta  ATL ATL (Georgia (U.S. state))  ATL ATL (the United States)  ATL ATL (North America) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Helipads | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hartsfield–Jackson is the primary hub of Delta Air Lines, and is a focus city for low-cost carriers Frontier Airlines and Southwest Airlines. With just over 1,000 flights a day to 225 domestic and international destinations, the Delta hub is the world's largest airline hub.[4][5] In addition to hosting Delta's corporate headquarters, Hartsfield–Jackson is also the home of Delta's Technical Operations Center, which is the airline's primary maintenance, repair and overhaul arm.[6]

The airport has international service within North America and to South America, Central America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. As an international gateway to the United States, Hartsfield–Jackson ranks seventh in international passenger traffic.[7] Many of the nearly one million annual flights are domestic flights; the airport is a major hub for travel in the southeastern region of the country. Atlanta has been the world's busiest airport by passenger traffic since 1998.[8]

The airport is mostly in unincorporated areas of Fulton and Clayton counties, but it spills into the city limits of Atlanta,[9] College Park,[10] and Hapeville.[11] The airport's domestic terminal is served by MARTA's Red and Gold rail lines.

History

.jpg)

Hartsfield–Jackson began with a five-year, rent-free lease on 287 acres (116 ha) that was an abandoned auto racetrack named The Atlanta Speedway. The lease was signed on April 16, 1925, by Mayor Walter Sims, who committed the city to develop it into an airfield. As part of the agreement, the property was renamed Candler Field after its former owner, Coca-Cola tycoon and former Atlanta mayor Asa Candler.[12] The first flight into Candler Field was September 15, 1926, a Florida Airways mail plane flying from Jacksonville, Florida. In May 1928, Pitcairn Aviation began service to Atlanta, followed in June 1930 by Delta Air Service. Later those two airlines, now known as Eastern Air Lines and Delta Air Lines, respectively, would both use Atlanta as their chief hubs.[13] The airport's weather station became the official location for Atlanta's weather observations September 1, 1928, and records by the National Weather Service.[14]

It was a busy airport from its inception and by the end of 1930 it was third behind New York City and Chicago for regular daily flights with sixteen arriving and departing.[15] (In May 1931 Atlanta had four scheduled departures.) Candler Field's first control tower opened March 1939.[16] The March 1939 Official Aviation Guide shows fourteen weekday airline departures: ten Eastern and four Delta.[17]

In October 1940, the U.S. government declared it a military airfield and the United States Army Air Forces operated Atlanta Army Airfield jointly with Candler Field. The Air Force used the airport primarily to service many types of transient combat aircraft. During World War II the airport doubled in size and set a record of 1,700 takeoffs and landings in a single day, making it the nation's busiest in terms of flight operation. Atlanta Army Airfield closed after the war.[16]

In 1942[18] Candler Field was renamed Atlanta Municipal Airport and by 1948, more than one million passengers passed through a war surplus hangar that served as a terminal building. Delta and Eastern had extensive networks from ATL, though Atlanta had no nonstop flights beyond Texas, St. Louis, and Chicago until 1961. Southern Airways appeared at ATL after the war and had short-haul routes around the Southeast until 1979.

In 1957 Atlanta saw its first jet airliner: a prototype Sud Aviation Caravelle that was touring the country arrived from Washington, D.C. The first scheduled turbine airliners were Capital Viscounts in June 1956; the first scheduled jets were Delta DC-8s in September 1959. The first trans-Atlantic flight was a Delta/Pan Am interchange DC-8 to Europe via Washington starting in 1964; the first scheduled international nonstops were Eastern flights to Mexico City and Jamaica in 1971–72. Nonstops to Europe started in 1978 and to Asia in 1992–93.

Atlanta claimed to be the country's busiest airport, with more than two million passengers passing through in 1957 and, between noon and 2 p.m. each day, it became the world's busiest airport.[16] (The April 1957 OAG shows 165 weekday departures from Atlanta, including 45 between 12:05 and 2:00 PM (and 20 between 2:25 and 4:25 AM).) Chicago Midway had 414 weekday departures, including 48 between 12:00 and 2:00 PM. In 1957, Atlanta was the country's ninth-busiest airline airport by flight count and about the same by passenger count.[19]

That year work began on a $21 million terminal which opened May 3, 1961. It was the largest in the country and could handle over six million travelers a year; the first year nine and a half million people passed through.[20] In March 1962 the longest runway (9/27, now 8R) was 7,860 feet (2,400 m); runway 3 was 5,505 feet (1,678 m) and runway 15 was 7,220 feet (2,200 m) long.

In 1971 the airport was named William B. Hartsfield Atlanta Airport after former Atlanta mayor William B. Hartsfield, who had died that year. The name change took effect on February 28, which would have been Hartsfield's 81st birthday. Later that year, in recognition of the growth of the airport's international service, the name was renamed to the William B. Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport.[21]

The airport's terminal until the 1970s was off Virginia Avenue, on the north side of the airport. Six pier concourses radiated from a central building.[22] Construction began on the present midfield terminal in January 1977 under the administration of Mayor Maynard Jackson. It was the largest construction project in the South, costing $500 million. The complex was designed by Stevens & Wilkinson, Smith Hinchman & Grylls, and Minority Airport Architects & Planners.[23] The new terminal opened on September 21, 1980, on-time and under budget.[24] It was designed to accommodate up to 55 million passengers per year and covered 2.5 million square feet (230,000 m²). In December 1984 a 9,000-foot (2,700 m) fourth parallel runway was completed and another runway was extended to 11,889 feet (3,624 m) the following year.[16]

In 1999 Hartsfield–Jackson's leadership established the Development Program: "Focus On the Future" involving multiple construction projects with the intention of preparing the airport to handle a projected demand of 121 million passengers in 2015. The program was originally budgeted at $5.4 billion over a ten-year period, but the total is now revised to be at over $9 billion.[25]

In May 2001 construction of an over 9,000-foot (2,700 m) fifth runway (10–28) began. It was completed at a cost of $1.28 billion and opened on May 27, 2006.[26] It bridges Interstate 285 (the Perimeter) on the airport's south side, making Hartsfield–Jackson the nation's only currently active civil airport to have a runway above an interstate (although Runway 17R/35L at Stapleton International Airport in Denver, Colorado crossed Interstate 70 until that airport closed in 1995). The massive project, which involved putting fill dirt eleven stories high in some places, destroyed some surrounding neighborhoods and dramatically changed the scenery of Flat Rock Cemetery and Hart Cemetery, both of which are on the airport property.[27] It was added to help ease traffic problems caused by landing small- and mid-size aircraft on the longer runways used by larger planes such as the Boeing 777, which need longer runways than the smaller planes. With the fifth runway, Hartsfield–Jackson is one of only a few airports that can perform triple simultaneous landings.[28] The fifth runway is expected to increase the capacity for landings and take-offs by 40%, from an average of 184 flights per hour to 237 flights per hour.[29]

Along with the fifth runway, a new control tower was built to see the entire length of the runway. The new control tower is the tallest in the United States, over 398 feet (121 m) tall. The old control tower, 585 feet (178 m) away from the new one, was demolished August 5, 2006.[30]

On October 20, 2003, the Atlanta City Council voted to rename the airport Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, to honor former mayor Maynard Jackson, who died June 23, 2003. The council planned to drop Hartsfield's name from the airport, but public outcry prevented this.[31][32]

In April 2007 an "end-around taxiway" opened, Taxiway Victor. It is expected to save an estimated $26 million to $30 million in fuel each year by allowing airplanes landing on the northernmost runway to taxi to the gate area without preventing other aircraft from taking off. The taxiway drops about 30 feet (9.1 m) from runway elevation to allow takeoffs to continue.[33]

After the Southeastern U.S. drought of 2007, the airport (the eighth-largest water user in the state) made changes to reduce water usage. This included adjusting toilets (725 commodes and 338 urinals) and 601 sinks. (The two terminals alone use 917,000 gallons or about 3.5 million liters a day.) It also stopped using firetrucks to spray water over aircraft when the pilot made a last landing before retirement (a water salute).[34][35] The city of Macon offered to sell water to the airport, through a proposed pipeline.[36]

The airport today employs about 55,300 airline, ground transportation, concessionaire, security, federal government, City of Atlanta, and airport tenant employees and is the largest employment center in Georgia. With a payroll of $2.4 billion, the airport has a direct and indirect economic impact of $3.2 billion on the local and regional economy and an annual, regional economic impact of more than $19.8 billion.[37] Since the opening of Concourse F in May 2012, the airport now has 192 gates which is the most at any airport.

In December 2015, the airport became the first airport in the world to serve 100 million passengers in a year.[38]

Historical airline service

Delta and Eastern dominated the airport during the 1970s. United, Southern, Piedmont, Northwest and TWA were also present.[39] In 1978, after airline deregulation, United no longer served Atlanta, while Southern successor Republic was the airport's third-largest carrier.[40]

Eastern was a larger airline than Delta until deregulation in 1978, but Delta was early to adopt the hub-and-spoke route system, with Atlanta as a hub between the Midwest and Florida, giving it an advantage in the Atlanta market. Eastern ceased operations in 1991 because of labor issues; American Airlines considered establishing an Atlanta hub around that time, but decided Delta was too strong there and instead replaced Eastern's other hub in Miami. TWA created a small hub at Atlanta in 1992 but abandoned the concept in 1994 leaving Delta with a monopoly hub at Atlanta.[41]

From the 1980s until Eastern's demise in 1991, Delta occupied Concourse A and part of Concourse B, Eastern occupied the remainder of Concourse B and Concourse C, other domestic airlines used Concourse D, and Concourse T was used by international flights.[42][43] By the mid-1990s, Delta's hub grew to occupy all of Concourse B and the southern half of Concourse T, and international flights moved to the new Concourse E.[44]

ValuJet was established in 1993 as low-cost competition for Delta at ATL. However, its safety practices were called into question early and the airline was grounded after the 1996 crash of ValuJet Flight 592. It resumed operations in 1997 as AirTran Airways and was the second-largest airline at ATL until it was acquired by Southwest in 2011 and absorbed into Southwest on December 28, 2014. Southwest is now the airport's second largest carrier.

Facilities

Runways

Atlanta has five runways, all parallel, aligned east–west. 8L/26R and 8R/26L are north of the terminal area and 9L/27R, 9R/27L, and 10/28 are south of it. From north to south the runways are:[2] 8L/26R, 8R/26L, 9L/27R, 9R/27L, 10/28

Runways 8R/26L and 9L/27R are used for departures: as they're the closest to the mid-field terminals, this reduces the amount of fuel needed to taxi to the runway. Runway 10/28 is assigned to either arrivals or departures, depending on what airfield operations has prioritized.[45]

Terminal

Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport has terminal and concourse space totaling 6.8 million square feet (630,000 m2).[2] There are two terminals, the Domestic Terminal and the Maynard H. Jackson Jr. International Terminal, where passengers check in and claim bags.

The Domestic Terminal is on the western side of the airport. It is divided into two sides – Terminal South and Terminal North – for ticketing, check-in, and baggage claim. Delta is the sole tenant of Terminal South, while all other domestic airlines are located at Terminal North. The portion of the building between Terminal North and Terminal South includes the Atrium, which is a large, open seating area featuring concessionaires, a bank, conference rooms, an interfaith chapel and offices on the upper floors with the main security checkpoint, the Ground Transportation Center and a MARTA station on other levels.[46]

International flights arrive and depart from the international terminal, either concourse E or F, located on the eastern side of the airport. Concourse F and the new international terminal opened May 16, 2012, while concourse E opened in September 1994, in anticipation of the 1996 Summer Olympics. International pre-cleared flights can arrive at concourses T & A–D. International flights can also depart from concourses T and A–D, such as when space is unavailable at concourses E or F, or when an aircraft arrives as a domestic flight and continues as an international flight. Furthermore, all international pre-cleared flights, regardless of origin, will collect their baggage at the international terminal. Concourse E only houses domestic and international Delta flights, whilst Concourse F houses all international carriers and some Delta international flights.

The 195 gates (more than any other airport in the world) are located in seven concourses between the Domestic and International terminals. Concourse T is connected to the Domestic Terminal. The remaining six concourses from west to east are Concourses A, B, C, D, E, and F.[2] Concourses A–D and T are used for domestic flights, while Concourses E and F are used for international flights and some domestic flights when gates at T or A–D are not available, or when an aircraft arrives as an international flight and continues as a domestic flight. Concourse F is directly connected to the International Terminal, while Concourse E has a designated walkway to the International Terminal and also has its own Federal Inspection station for connecting passengers. Delta Air Lines has gates and Sky Club lounges in all concourses. American Airlines and United Airlines have an Admiral's Club and a United Club respectively in Concourse T.

- Concourse T contains 17 gates

- Concourse A contains 29 gates

- Concourse B contains 32 gates

- Concourse C contains 34 gates

- Concourse D contains 40 gates

- Concourse E contains 28 gates

- Concourse F contains 15 gates; Gate F3 was configured for and can handle an Airbus A380

When the current passenger terminal opened in 1980, it consisted of only the domestic terminal, the north half of Concourse T (which housed international flights), and concourses A-D. Concourse E opened in 1994 for international flights in time for the 1996 Summer Olympics, which were held in Atlanta.[16] Once Concourse E was opened, Concourse T was converted to domestic use and the former U.S. Customs hall was converted into a dedicated baggage claim area for American Airlines. Concourse F and the International Terminal opened in 2012.

The terminals and concourses are connected by the Transportation Mall, a pedestrian tunnel with a series of moving walkways,[47] and The Plane Train, an automated people mover. The Plane Train has stations along the Transportation Mall at the Domestic Terminal (which also serves Concourse T), at each of the six other concourses (including concourse F which is connected to the International Terminal), and at the domestic baggage claim area. The Plane Train is the world's busiest automated system, with over 64 million riders in 2002.[47]

At one time, there was a second underground walkway between Concourses B and C that connected the north ends of the two concourses and made it possible to transfer without returning to the center of the concourse. This was constructed for Eastern Airlines, which occupied these two terminals. This walkway is now closed, and its entrance at Concourse B has been replaced by a bank of arrival/departure monitors.

Ground transportation

The domestic terminal is accessed directly from Interstate 85 at exit 72. The international terminal is accessed directly from Interstate 75 at exit 239. These freeways in turn connect with the following additional freeways within 10 miles: Interstate 285, Interstate 675, Georgia State Route 166, Interstate 20.

Hartsfield–Jackson has its own train station on the city's rapid transit system, MARTA. The above-ground station is inside in the main building, between the north and south domestic terminals on the west end. The Airport station is currently the southernmost station in the MARTA system, though expansion via metro or commuter rail further south into Clayton County have been discussed.[48]

The Hartsfield–Jackson Rental Car Center, which opened December 8, 2009, houses all ten airport rental agencies with capacity for additional companies. The complex features 9,900 parking spaces split between two four-story parking decks that together cover 2.8 million square feet (260,000 m2), a 137,000-square-foot (12,700 m2) customer service center, and a maintenance center featuring 140 gas pumps and 30 wash bays equipped with a water recovery system. An automated people mover, the ATL SkyTrain, runs between the rental car center, the Domestic Terminal, and the Gateway Center of the Georgia International Convention Center,[49] while a four-lane roadway that spans Interstate 85 connects the rental car center with the existing airport road network.[50]

Other facilities

The 990 Toffie Terrace hangar, a part of Hartsfield–Jackson Airport,[51] and located within the City of College Park corporate limits, is owned by the City of Atlanta.[10] The building now houses the Atlanta Police Department Helicopter Unit.[52][53] It once served as the headquarters of the regional airline ExpressJet.[54]

Before the merger, Atlantic Southeast Airlines headquartered in the hangar, then named the A-Tech Center.[55] In December 2007, the airline announced it was moving its headquarters into the facility, previously named the "North Hangar." The 203,000-square-foot (18,900 m2) hangar includes 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of hangar bays for aircraft maintenance. It has 17 acres (6.9 ha) of adjacent land and 1,400 parking spaces for employees. The airline planned to relocate 100 employees from Macon to the new headquarters. The Atlanta City Council and Mayor of Atlanta Shirley Franklin approved of the new 25-year ASA lease, which also gave the airline new hangar space to work on 15 to 25 aircraft in overnight maintenance; previously its aircraft were serviced at Concourse C. The airport property division stated that the hangar was built in the 1960s and renovated in the 1970s. Eastern Airlines and Delta Air Lines had previously occupied the hangar. Delta's lease originally was scheduled to expire in 2010, but the airline returned the lease to the City of Atlanta in 2005 as part of its bankruptcy settlement. The city collected an insurance settlement of almost $900,000 as a result of the cancellation.[51]

A VOR station, identified as ATL, is located on the airport property, slightly southwest of the center of runway 9R/27L.[56]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

- Notes

- ^1 : This Delta flight will operate via Johannesburg in a triangle route (ATL-JNB-CPT-ATL) as an addition to ATL-JNB routing. However, Delta does not plan to have rights to transport passengers solely between Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Cargo

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Airlines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orlando, Florida | 1,190,000 | Delta, Frontier, JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit |

| 2 | Fort Lauderdale, Florida | 1,058,000 | Delta, JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit |

| 3 | New York–LaGuardia, New York | 944,000 | American, Delta, Frontier, Southwest |

| 4 | Los Angeles, California | 888,000 | American, Delta, Frontier, Southwest, Spirit |

| 5 | Tampa, Florida | 860,000 | Delta, Southwest, Spirit, Frontier |

| 6 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 752,000 | American, Delta, Spirit |

| 7 | Boston, Massachusetts | 721,000 | Delta, JetBlue, Spirit |

| 8 | Miami, Florida | 715,000 | American, Delta, Frontier |

| 9 | Denver, Colorado | 714,000 | Delta, Southwest, Spirit, Frontier, United |

| 10 | Baltimore, Maryland | 698,000 | Delta, Southwest, Spirit |

| Rank | Airport | Scheduled Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paris, France | 849,736 | Air France, Delta |

| 2 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 812,286 | Delta, KLM |

| 3 | Cancún, Mexico | 740,837 | Delta, Southwest |

| 4 | London–Heathrow, United Kingdom | 644,081 | British Airways, Delta, Virgin Atlantic |

| 5 | Toronto–Pearson, Canada | 547,882 | Air Canada, Delta |

| 6 | Mexico City, Mexico | 450,045 | Delta |

| 7 | Punta Cana, Dominican Republic | 389,304 | Delta, Southwest |

| 8 | Montego Bay, Jamaica | 356,408 | Delta |

| 9 | Nassau, Bahamas | 317,594 | Delta |

| 10 | Frankfurt, Germany | 291,450 | Delta, Lufthansa |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Delta Air Lines | 69,313,000 | 72.86% |

| 2 | Southwest Airlines | 8,809,000 | 9.26% |

| 3 | Endeavor Air | 4,657,000 | 4.90% |

| 4 | American Airlines | 2,775,000 | 2.92% |

| 5 | Spirit Airlines | 2,684,000 | 2.82% |

Annual traffic

| Passengers | Change from previous year | Aircraft operations | Cargo tonnage[84] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 78,092,940 | N/A | 935,892 | |

| 2001 | 80,162,407 | 915,454 | 865,991 | |

| 2002 | 75,858,500 | 890,494 | 735,796 | |

| 2003 | 76,876,128 | 889,966 | 734,083 | |

| 2004 | 79,087,928 | 911,727 | 802,248 | |

| 2005 | 83,606,583 | 964,858 | 862,230 | |

| 2006 | 85,907,423 | 980,386 | 767,897 | |

| 2007 | 84,846,639 | 976,447 | 746,502 | |

| 2008 | 89,379,287 | 994,346 | 720,209 | |

| 2009 | 90,039,280 | 978,824 | 655,277 | |

| 2010 | 88,001,381 | 970,235 | 563,139 | |

| 2011 | 92,389,023 | 923,996 | 659,129 | |

| 2012 | 94,956,643 | 952,767 | 684,576 | |

| 2013 | 94,431,224 | 911,074 | 616,365 | |

| 2014 | 96,178,899 | 868,359 | 601,270 | |

| 2015 | 101,491,106 | 882,497 | 626,201 | |

| 2016 | 104,258,124 | 898,356 | 648,595 | |

| 2017 | 103,902,992 | 879,560 | 685,338 | |

| 2018 | 107,394,029 | 895,682 | 693,790 | |

| 2019 | 110,531,300 | 904,301 | 639,276 | |

| Source: Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport[7] | ||||

Accidents and incidents

- On May 23, 1960, Delta Air Lines Flight 1903, a Convair CV-880-22-1 (N8804E), crashed on takeoff resulting in the loss of all four crew members. This flight was to be a training flight for two Delta captains who were being type-rated on the 880.[85]

- On February 25, 1969, Eastern Air Lines Flight 955 was hijacked by one passenger shortly after takeoff from ATL en route to Miami. The man pulled a .22 caliber pistol and demanded to be flown to Cuba. He got off the plane in Cuba while the DC-8 was allowed to fly back to the U.S.[86]

- On January 18, 1990, an Eastern Airlines Boeing 727 overran a Beechcraft King Air operated by Epps Air Service, based at another Atlanta airport. The King Air had landed and was taxiing when the 727, still at high speed in its landing roll, collided with the aircraft. The larger plane's wing impacted the roof of the smaller. The pilot of the King Air, an Epps charter pilot, was killed, while a passenger survived. No crew or passengers of the Eastern plane were injured.[87]

See also

- Atlanta's second airport

- Candler Field Museum

- Georgia World War II Army Airfields

- List of busiest airports by aircraft movements

- List of busiest airports by cargo traffic

- List of busiest airports by international passenger traffic

- List of busiest airports by passenger traffic

- List of the busiest airports in the United States

- World's busiest airport

References

- "Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport Statistics". Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- "Fact Sheet". Atlanta Department of Aviation. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- "FAA Airport Master Record for ATL" (PDF). AirportIQ. Federal Aviation Administration. January 30, 2020.

- "Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport". Delta Air Lines. Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- "Delta Hub Station". Archived from the original on June 26, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- "Delta TechOps". CAPA Centre for Aviation. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "Operating Statistics". Atlanta Department of Aviation. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- Tan, Huileng (December 20, 2017). "If you're surprised that Atlanta has the busiest airport on earth, you're not alone". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 25, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- "Zoning Ordinance, City of Atlanta, Georgia; Sheet 32" (PDF). City of Atlanta. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "City Map". City of College Park. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "Official Zoning Map". City of Hapeville. January 6, 2009. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Anita Price Davis (2014). The Margaret Mitchell Encyclopedia. McFarland. p. 47. ISBN 9780786492459.

- Eastern Airlines History, Facts and Pictures Archived September 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. (Since 2003). In Aviation Explorer. Retrieved September 14, 2010

- "Station Thread for Atlanta Area, GA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Garrett, Franklin (1969). Atlanta and Its Environs. II. University of Georgia Press. p. 851. ISBN 978-0-8203-0913-2. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "Airport History". Atlanta Department of Aviation. Archived from the original on March 1, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- This predecessor of today's OAG was published monthly by the Official Aviation Guide Co of Chicago.

- Hartsfield, Dale (December 5, 2014). Leonard, Donna Garrison (ed.). What's In A Name? A Historical Perspective of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (1st ed.). Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-5054-0027-4. OCLC 930872527.

- Federal Airways Air Traffic Activity for Calendar 1957

- Henderson, David (November 2008). Sunshine Skies: Historic Commuter Airlines of Florida and Georgia. Atlanta: Zeus Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-4404-2474-8. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- "History of ATL - ATL - Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport". Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- "Atlanta International Airport – 1975". DepartedFlights.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- Walters, Helen (January 23, 2007). "Now Arriving: A New Generation of Airports". Business Week. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "Maynard Jackson, Jr". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. June 25, 2003. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Tobin–Ramos, Rachel (September 21, 2007). "Hartsfield Project Costs Soar to $9B". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- "Atlanta International Airport: Fifth Runway". Atlanta Department of Aviation. May 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2007.

- "Flat Rock Cemetery". Tomitronics. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- "Aviation "Bridges" the Gap for Future Growth". Williams-Russell and Johnson, Inc. Archived from the original on May 25, 2006. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- "Atlanta International Airport: Benchmark Results" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007.

- "Atlanta Airport Demolishes Old Air Traffic Control Tower". Airport Business. Associated Press. August 7, 2006. Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- Halbfinger, David M. (August 13, 2003). "Atlanta Is Divided Over Renaming Airport for Former Mayor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 17, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- "Atlanta Airport to be Renamed Hartsfield–Jackson". Airline Industry Information. M2 Communications, LTD. October 21, 2003. Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- Tharpe, Jim (March 18, 2007). "An End-Around to Efficiency: Hartsfield–Jackson Strip Offers Safety, Boosts Capacity". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on March 22, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Tharpe, Jim (October 29, 2007). "Airport Hoping to Flush Away Less Water". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- "Fewer, Faster Flushes for Airport Toilets". WSB News. Atlanta. October 29, 2007. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- "Drought: Macon Offers Water to ATL Airport". Georgia Public Broadcasting News. October 24, 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- "Financial Statements June 30, 2007 and 2006" (PDF). Atlanta Department of Aviation. June 30, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008.

- Mutzabaugh, Ben (December 28, 2015). "Atlanta is world's first airport to hit 100 million passengers in year". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- "ATL74intro". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "ATL79intro". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Petzinger, Thomas (1996). Hard Landing: The Epic Contest For Power and Profits That Plunged the Airlines into Chaos. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-77449-1.

- "ATL0684". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "ATL91". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "ATL95". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "ATL Airport Capacity Profile" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- "2005 Annual Report" (PDF). Atlanta Department of Aviation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- "Transportation Mall/People Mover". Atlanta Department of Aviation. Archived from the original on June 17, 2007. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- "Airport Station Helper". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Yamanouchi, Kelly (December 8, 2009). "Hartsfield–Jackson to open new rental car center". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Atlanta-airport.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "HJAIA – Airport Construction". City of Atlanta. Archived from the original on October 19, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Tobin–Ramos, Rachel; Sams, Douglas (December 10, 2007). "ASA Lands Headquarters at Hartsfield Hangar". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- "A Resolution by Transportation Committee (Adopted Version)" (PDF). City of Atlanta. October 3, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 18, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- "A Resolution by Transportation Committee (Proposed Version)" (PDF). City of Atlanta. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- "Contact Us". ExpressJet. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- "Contact Us". Atlantic Southeast Airlines. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

Atlantic Southeast Airlines A-Tech Center 990 Toffie Terrace Atlanta, GA 30354-1363

- "AirNav: Hartsfield - Jackson Atlanta International Airport". Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Flights to Atlanta, GA". Air Choice One. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- "Horaires". Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Flight timetable". Alaskaair.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Route Map and Schedule". Boutiqueair.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Timetables". Britishairways.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- https://beta.regulations.gov/document/DOT-OST-2020-0051-0001

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- Jim Liu (June 7, 2020). "Delta NW20 Boeing 777 network changes as of 07JUN20". www.routesonline.com/news. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Frontier". Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". B6.innosked.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Timetable". Klm.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Flight Status & Schedules". Koreanair.com. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Timetable". Luthansa.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Flight timetable". Booking.qatarairways.com. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Southwest Airlines Extends Published Flight Schedule Through Jan. 4, 2021". Southwest Airlines. May 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- "Check Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Where We Fly". Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Online Flight Schedule". Turkish Airlines. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Timetable". United.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "Interactive flight map". Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- "WestJet - Flight schedule". Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- "Airbridgecargo airlines adds atlanta to north american route network" (Press release). November 20, 2015. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- http://199.119.0.52/webfids/webfids_cargo

- "Atlanta, GA: Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International (ATL)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Aviation and International Affairs (June 20, 2017). U.S.-International Passenger Raw Data for Calendar Year 2016 (Report). US Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- Total cargo (Freight, Express, & Mail).

- Accident description for N8804E at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on December 13, 2017.

- Hijacking description at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on May 25, 2017.

- Ap (January 19, 1990). "1 Killed as Eastern Jet Rams a Small Plane on an Atlanta Runway". Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport. |

- Official website

- Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport Official YouTube

- Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport 1961–1980

- Historic photos of Atlanta Airport – Over 100 pages of historic ATL photos including dozens of vintage photos from the LIFE archive.

- Atlanta Airport Time Machine – ATL Airport historian David Henderson's Google Maps mashup featuring historical locations and associated photography.

- Atlanta airport travel data at Airportsdata.net

- Atlanta Airport Parking Guide

- Airport webcams, flight timetables & pilot data

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective August 13, 2020

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KATL

- ASN accident history for ATL

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KATL

- FAA current ATL delay information